Two Economic and Financial Periods with Similarities, But with Different International Monetary Systems: 1920-1929 and 2008-2024

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Global Research Wants to Hear From You!

***

“There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency… The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner, which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.“ John Maynard Keynes (1883-1946). British economist, (in ‘The Economic Consequences of the Peace’, 1919, Ch. VI, pp. 235-236).

“The survivors of a generation that has been of military age during a bout of war will be shy, for the rest of their lives, of bringing a repetition of this tragic experience either upon themselves or upon their children, and… therefore the psychological resistance of any move towards the breaking of a peace… is likely to be prohibitively strong until a new generation … has had time to grow up and to come into power.” Arnold J. Toynbee (1889-1975), British historian, (in ‘A Study of History’, vol. 9, 1954).

“When every country turned to protect its own private interest, the world public interest went down the drain, and with it the private interests of all.” Charles Kindleberger (1910-2003). American economic historian, (in his book ‘The World Depression 1929-1939’, 1973).

***

Introduction

Next year will be the 80th anniversary of the end of the Second World War (1939-1945). It is therefore likely that the world is approaching the end of the long post-war period, which has spanned three generations.

Likewise, in just a few years, it will be the 100th anniversary of the massive stock market crash in the autumn of 1929, which preceded the advent of the Great Depression (1929-1939).

Even though economic history does not necessarily repeat itself in every detail, there are long economic cycles in capitalist economies, which tend to repeat themselves at various intervals, provided that the economic imbalances and financial excesses which activate them are strong enough. Indeed, there are presently economic, financial and geopolitical circumstances that have some similarities with those that prevailed in the past, especially during the decade of the Roaring Twenties in the 1920’s, and even later during the 1930’s.

I. The Economic and Financial Situations in the United States During the 1920’s

The end of WWI in 1918 was followed by the influenza pandemic of 1918-1919, (it was called the Spanish flu pandemic because the press in Spain was the first to report it). It was a severely contagious viral disease that created numerous social and economic problems worldwide. Schools were closed, public gatherings prohibited and mortality rates rose.

However, after the pandemic and the brief but deep economic recession that followed, in 1920-1921, the American economy embarked upon a period of strong economic growth and widespread prosperity. It strongly benefited from the postwar reconstruction boom and from the emergence of many industrial innovations in the automobile, airline, telephone, radio, cinema and electric appliances industries, etc.

Manufactured consumer goods became more widely available to households through mass production. The US economy grew by 42 percent during the rest of the decade, from 1922 to 1929, as the building of roads, airports, gas stations, etc. progressed to meet the new needs in infrastructures. Unemployment was falling sharply and there was great optimism. However, this led to an overheated economy and to asset bubbles, especially in the stock market.

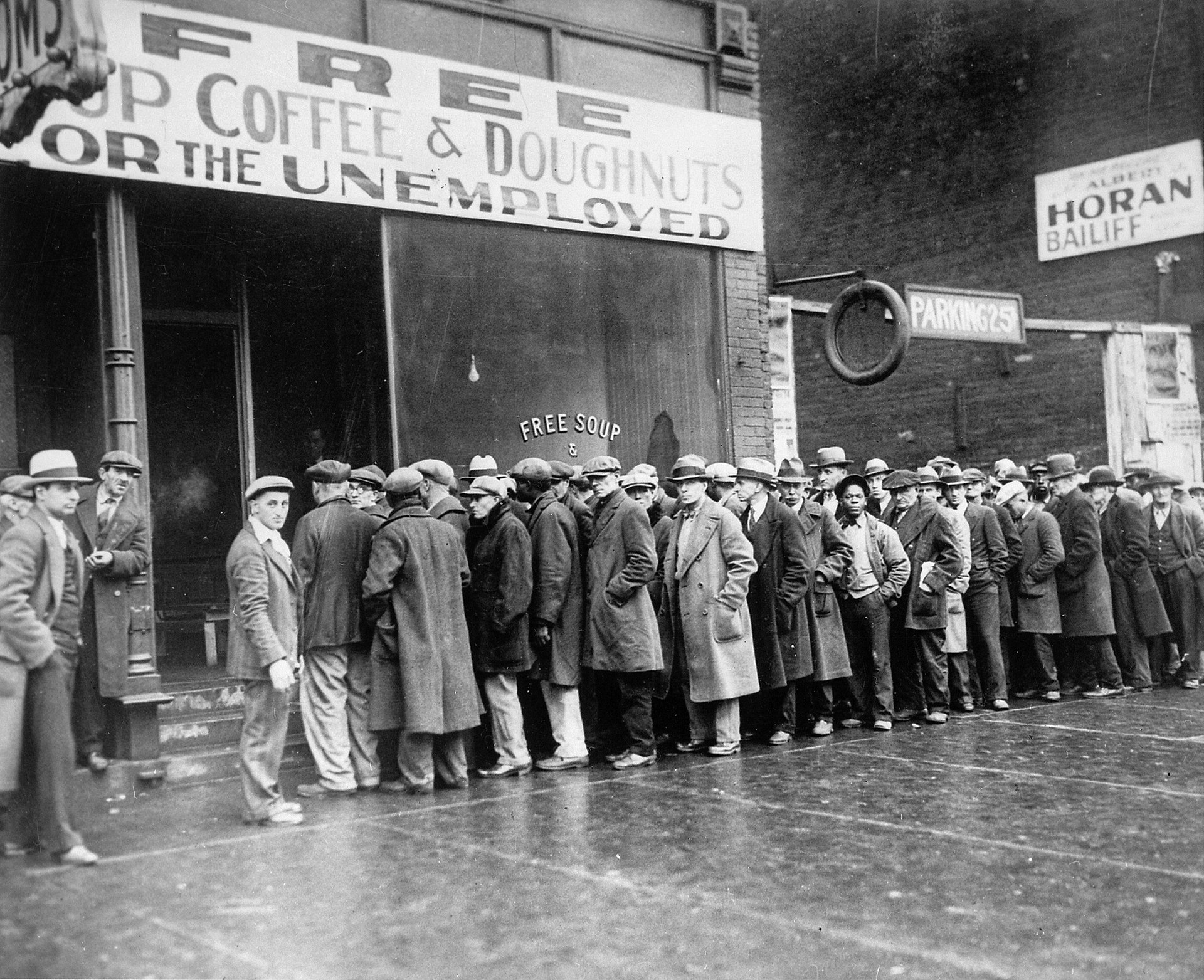

Indeed, the main reason the decade of 1920-1929 is so well remembered is because it led to the Great Depression of 1929-1939. The economy collapsed, deflation prevailed and unemployment reached a record high of 24.7 percent, in 1933.

Unemployed people lined up outside a soup kitchen in Chicago. (From the Public Domain)

During the 1920’s, behind the façade of prosperity, there were major economic imbalances and financial excesses that developed, not only in the United States, but worldwide. The first consequences of these drawbacks were the Wall Street stock market crash of 1929 and the economic recession, which rapidly morphed into an economic depression that lasted a decade. Also, an important international bank, the Austrian Creditanstalt bank, failed in May 1931. This led to other bank failures and created banking panics in the U.K., in the USA and in other countries.

And when later on, countries began to adopt inward-looking protectionist trade policies, international trade contracted and the global economy as a whole collapsed.

Declining Interest Rates and Stock Market Speculation in the 1920’s

To counteract a mild economic recession in 1927, the Fed lowered its discount rate in September of that year, from 4% to 3.5%.

Nevertheless, even though short-term interest rates were still low, they were higher than longer-term rates, and this was the case in 1927, 1928, and 1929. That translated into an inverted yield curve, as opposed to a normal situation when longer rates are higher than shorter rates, since longer loans are riskier than shorter ones. Usually, this indicates a situation of tight banking credit lending conditions.

An inverted yield curve is one of the most accurate predictors of a future economic slowdown or a recession, since nearly all economic recessions since the 1920’s, including the onset of the Great Depression in 1929, have taken place after such a warning that an economic slowdown was unfolding.

During the years of 1927-1929, the financial warning sign of the inverted yield curve was ignored and speculation in the stock market only got worse. At the time, speculators big or small could buy shares in companies by investing on margin, with as little down as 10 percent of the value, while borrowing the rest from banks or brokers. This led, from 1923 to 1929, to a six-year stock market bull run, when stock prices kept rising on average by 20 percent, each year. This was clearly an unsustainable pace.

After having vainly admonished banks and brokers to restrict their loans to speculators, the Fed finally decided to raise its discount rate three times, (the rate the Fed charges member banks for loans), between January and July 1928, from 3.5% to 5%. However, this turned out to be insufficient, because stock market speculation didn’t slow down. The Fed again raised its discount rate in August 1929, from 5 percent to 6 percent. That’s what broke the camel’s back!

The rest is history. The economic recession began in the United States in August 1929, as the economy started to shrink. However, the stock market only peaked on Tuesday, September 3, 1929, one day after Labor Day, but it began crashing for good on Black Thursday, Oct. 24, 1929.

II. The Subprime Mortgage Crisis of 2007-2008 and the Great Recession of 2008-2009

Let’s see how things stack up nowadays, financially and economically.

In the aftermath of the Subprime Mortgage Crisis of 2007-2008, and during the Great Recession of 2008-2009, governments and central banks of a number of countries changed profoundly their fiscal and monetary policies, especially in the United States.

Image: A continuous buildup of toxic assets in the form of subprime mortgages purchased by Lehman Brothers ultimately led to the firm’s bankruptcy in September 2008. The collapse of Lehman Brothers is often cited as both the culmination of the subprime mortgage crisis, and the catalyst for the Great Recession in the United States. (Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

Indeed, there was a real fear among government officials, during the fateful years of 2007-2008, that the entire American financial system could collapse and bring down the economy. The American banking system was already severely weakened by the collapse of the large investment bank Lehman Brothers, and by the rescue in panic of the investment banks Bears Stearns and Merrill Lynch. It was then judged necessary to adopt extreme measures to bail out the system.

That is when the Fed adopted a novel form of monetary policy of extraordinary accommodation called “Quantitative Easing” (QE). The idea was that in such a time of financial trouble, it was not sufficient to lower interest rates and to advance loans to banks in trouble.

What was required was to flood financial markets with huge amounts of newly created liquidity, which is accomplished when a central bank purchases for its own account large quantities of Treasury bonds or private securities on the secondary market. If necessary, such a practice can push nominal interest rates to zero or to close to zero. This was the case in the United States when the federal funds rate (rate at which private banks borrow from each other for very short periods) was kept by the Fed close to zero, from 2008 to 2016, and again, from 2020 to 2022.

The Economic Consequences of Quantitative Easing on Debtors

A Quantitative Easing monetary policy risks creating two problems. First, it tends to create important price bubbles in the stock and bond markets. Secondly, artificially low interest rates run the risk of encouraging consumers, businesses and governments alike to go deeper into debt. This raises the question of moral hazard when public policies encourage people to alter their normal prudent behavior and take bigger risks.

This is an important consideration nowadays, since the sum of all consumer, business and government debts in the world, the global debt, reached the record high level of $307 trillion in 2023, according to the Institute of International Finance. This has pushed the global debt-to GDP ratio to 336 percent.

In the event of a rise in inflation, accompanied by an increase in interest rates and mortgage rates, debtors in general who have become heavily indebted while interest rates were ultra low, may find themselves caught in a dangerous debt trap. Households and consumers, for example, who are saddled with high mortgage debts and credit debts, may have to renew their loans at much higher interest rates, thereby facing the unattractive prospect of making monthly payments that are inflated relative to their incomes.

III. The Major Differences Between the 1920-1929 Period and the 2008-2024 Period

The main difference between the 1920-1929 economic decade and the current economic and financial period since 2008 is the fact that the international monetary systems were different during these two periods.

The gold standard (1879-1933) had been suspended at the start of WWI, in 1914, but it had been reinstated in most major economies, including the United States, by 1925. It was an international monetary system in which the value of a standard unit of a currency was based on a fixed quantity of gold. For instance, if the official price of one ounce of gold was set at $20, that meant the one US dollar was worth 1/20 ounce of gold and could be exchanged at that price.

The Gold Standard had the advantage of imposing a strict discipline on governments regarding spending and borrowing and thus to prevent inflation. Indeed, with such a system, a government was less able to run large fiscal deficits, because the central bank could not print money at will to accommodate its need of funds. The government had to sell Treasury bonds to the public to cover its excess spending over its tax revenues.

For example, countries running an external deficit in their balance of payments ran the risk of losing gold, while those countries with an external surplus stood to gain gold. The consequence was that central banks could not increase their country’s money supply at will, for fear of creating an external deficit and of losing gold. In the latter case, the domestic money supply would contract and this would place a deflationary burden on the economy. That is why the Gold Standard had, in general, a deflationary bias.

The Bretton Woods Monetary System of 1944

After WWII, the Gold Standard monetary system, which had been suspended in 1933, was replaced by the Bretton Woods monetary system. It was called a Gold Exchange Standard system, which meant that only the American dollar remained freely convertible into gold, at an official price of $35 an ounce, while other countries’ currencies had an exchange rate pegged to the US dollar.

The price of gold, as denominated in US dollars, was stable until the collapse of the Bretton Woods system in the mid-1970s. (Licensed under CC0)

However, the US dollar became officially a genuine fiat currency on August 15, 1971, when the Nixon administration cancelled the official convertibility of the dollar into gold. This meant the end of the fixed exchange rate system. Shortly after, in fact, most other countries adopted a floating exchange-rate system for their fiat currencies. This is the international payment and exchange system that exists today. Contrary to the Gold Standard, the system of floating exchange rates for fiat currencies tends to be inflationary.

Digital Cryptocurrencies and Geopolitical Risks

To add to the overall speculative nature of our era, one must also mention the rise of the internet-based digital cryptocurrencies phenomenon, which began in 2009 with the creation of the Bitcoin. This is a system of digital assets with widely fluctuating prices. It is somewhat reminiscent of the exotic Tulip bubble, which took place in the Netherlands in the early part of the 17th century.

Also, it is important to note that geopolitical tensions between great powers are much more prevalent today than they were in the 1920’s. This is reflected in the current turmoil in international relations. It is a state of affairs somewhat similar to the one prevailing during the later part of the 1930 decade.

At the time, the League of Nations was incapable of preventing or of ending regional military conflicts, just as the United Nations nowadays is unable to maintain world peace. Therefore, in the coming years, serious military confrontations between great powers cannot be excluded, and this could be an additional cause of financial and economic dislocations, as it could mean higher oil prices and higher inflation.

Conclusions

There are similarities but also important differences between the economic and financial situations prevailing in the 1920’s and those unfolding int the current 2008-2024 period.

Both periods saw changing economic times, characterized by major economic imbalances and speculative excesses in financial markets.

The main financial similarity between the two periods is the prevalence of an inverted yield curve in both cases, which could hint at future financial and economic troubles. It remains to be seen whether financial and economic difficulties will unfold in the coming months or years, as it was the case in 1929.

On the other hand, the international monetary system in force during each period was completely different. In the first case, it was the Gold Standard system that prevailed. Currently, the world economy is under a system of floating exchange rates of fiat national currencies, with the US dollar serving as the main currency of exchange and for most of the official reserves of central banks.

However, such a system is presently in a flux, as many countries, especially those of the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa and others), are trying to escape the arbitrary financial sanctions that the US government imposes sometimes on some countries, for political reasons. This would explain the efforts of the latter countries to develop other means of payments to conduct their international trade and financial transactions.

If and when a financial crisis or a severe economic downturn were to unfold in the future, triggered by some unforeseen event, it is likely that governments and central banks would respond by adopting the same policies as they did at the onset of the Covid-related economic lockdowns in 2020.

First, the governments of major advanced economies would be expected to increase their fiscal deficits, already very high. Secondly, central banks would try to accommodate governments and financial markets alike, by injecting large amounts of liquidity into the economy, through a policy of ‘Quantitative Easing’.

However, such extraordinary interventions are not without risk. Indeed, after the initial deflationary shock of a financial crisis, which would be followed by a recession, overly expansionary budgetary and monetary policies, possibly associated with protectionist trade policies similar to those adopted in the 1930’s, could result in a period of widespread stagflation, that is a period of slow economic growth and of persistent inflation.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

This article was originally published on the author’s blog site, Dr. Rodrigue Tremblay.

International economist Dr. Rodrigue Tremblay is the author of the book about morals “The code for Global Ethics, Ten Humanist Principles” of the book about geopolitics “The New American Empire“, and the recent book, in French, “La régression tranquille du Québec, 1980-2018“. He was Minister of Trade and Industry (1976-79) in the Lévesque government. He holds a Ph.D. in international finance from Stanford University. Please visit Dr Tremblay’s site or email to a friend here.

Prof. Rodrigue Tremblay is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

The Code for Global Ethics: Ten Humanist Principles

by

Publisher: Prometheus (April 27, 2010)

Hardcover: 300 pages

ISBN-10: 1616141727

ISBN-13: 978-1616141721

Humanists have long contended that morality is a strictly human concern and should be independent of religious creeds and dogma. This principle was clearly articulated in the two Humanist Manifestos issued in the mid-twentieth century and in Humanist Manifesto 2000, which appeared at the beginning of the twenty-first century. Now this code for global ethics further elaborates ten humanist principles designed for a world community that is growing ever closer together. In the face of the obvious challenges to international stability-from nuclear proliferation, environmental degradation, economic turmoil, and reactionary and sometimes violent religious movements-a code based on the “natural dignity and inherent worth of all human beings” is needed more than ever. In separate chapters the author delves into the issues surrounding these ten humanist principles: preserving individual dignity and equality, respecting life and property, tolerance, sharing, preventing domination of others, eliminating superstition, conserving the natural environment, resolving differences cooperatively without resort to violence or war, political and economic democracy, and providing for universal education. This forward-looking, optimistic, and eminently reasonable discussion of humanist ideals makes an important contribution to laying the foundations for a just and peaceable global community.