Droughts in China

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Up to 33 million tons of crops are lost each year to drought. A severe drought in the spring and summer of 2001 stretched across 17 provinces and left 23 million people short of drinking water and damaged 73 million acres of farmland. Hundreds of sheep and cattle died of dehydration.

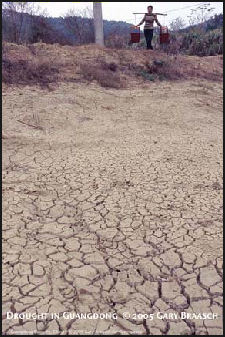

A severe drought on Guangxi in 2004 produced withered crops and massive power losses due to lack of water for hydro power generation. More than 1,100 reservoirs went dry. In neighboring Guangdong Province 1 million people didn’t have enough drinking water. The drought was partly the result of typhoons failing to strike the region.

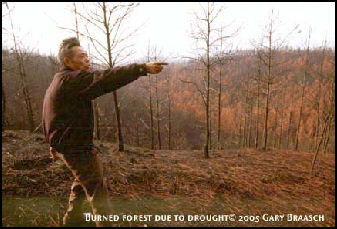

The worst drought in 50 years struck Guangdong Province in 2005. The drought was especially bad because it struck during the rice planting season and was exacerbated by high water usage. The drought affected the power supply and in some places factories only operated during the night because that was the only time electricity was available.

China’s state meteorologists have blamed an increase in the number of extreme weather events in recent years on climate change. But the drought has been intensified by massive deforestation and the pollution and depletion of water resources caused by China’s heady pursuit of economic growth, said Ma Jun, author of “China’s Water Crisis”. “There is such a tight eco-balance now that whenever we have a problem with a natural climate phenomenon, it causes a big disaster. We don’t have much extra capacity to absorb the impact,” he said. [Source: Dan Martin, AFP, March 29, 2010]

Drought in China in 2006 and 2007

The worst drought in more than century struck southwest China and Sichuan in the summer of 2006. Chonquing suffered repeated heat waves, record highs of 44.5̊C and hardly any rain in July or August. In the grain producing areas of Sichuan huge swath of farmland withered after rainfall in the rainy season in early summer was the lowest since 1947. The water levels of the Yangtze were the lowest in the past century.

The drought cost more than $1.1 billion in crop damage in Sichuan, Guizhou, Hubei, Hunan, Zhejiang, Anhui and Jiangxi Provinces. More than 5 million tons of sweet potatoes and beans were lost, 11 million hectares of mostly rice, corn and tobacco were destroyed or damaged.

The drought affected all of China. In Guangdong a salt tide caused in part by a dropping water table affected drinking water supplies. In Inner Mongolia well water ran out and goats and sheep were fed from tanker trucks. Horses and cattle starved. For a time 18 million people nationwide had no access to clean drinking water.

The area around the Yangtze River suffered a severe drought in 2007. In some places water levels of the river dropped to their lowest levels since records began 142 years ago. Between October and December 2007 forty ships ran aground in the main course of the river. The drought was also severe in large areas of the normally wet south. Reservoirs and rivers shrunk and supplies of drinking water fell to alarmingly low levels.

Drought in Southwest China in 2009 and 2010

A severe drought in the southwestern provinces of Yunnan, Guangxi, Sichuan and Guizhou in 2009-2010 was the worst there in over a century. In areas of the normally wet region there was hardly any rain for months. Reservoirs were empty; river beds were dry; hillsides and terraces normally full of crops looked like deserts; the rich soil was like rock; people got sick from drinking contaminated water. It seem liked half the people in some parts of the region spent most of their day carrying water with shoulder poles from distant wells to their homes or fields. More than 90 percent of the hydro power stations in Guizhou, the worst-hit province, were not operating.

One farmer told AFP his family barely had enough water to drink water to drink and was forced to go weeks without bathing. To get water for his chestnut and walnut trees the farmer trekked long distance and carries back water on a shoulder pole. Damages to his crops has cut his earnings by 80 percent. “I’m 64, and this is the driest I have ever seen it,” said another farmer, who lost half his crop and half his income. “My biggest fear is that if it continues to be so dry , the impact on the harvest will be severe.”

According to government estimates 60 million were affected and 18 million people and 11 million livestock were short of water. Total economic costs exceeded $3 billion. Some blamed global warming. Others said that deforestation and depletion of water sources by economic activity were involved. To help he Chinese government dug thousands of wells, trucked in drinking water and carried out emergency water diversion projects. Clouding seeding efforts were futile.

Dan Martin wrote AFP,

“The drought plaguing Yunnan, Guizhou and Sichuan provinces, the Guangxi region and the mega-city of Chongqing has been called the worst in a century. It has devastated crops, fueled price rises and highlighted China’s chronic water problems. Since last September, rainfall has been less than half the normal levels, turning much of normally temperate Yunnan into a bone-dry environmental disaster zone of evaporating reservoirs and shrivelled rivers.”[Source: Dan Martin, AFP, March 29, 2010]

“Terraced fields that should be bursting green with winter crops instead resemble dusty deserts, their normally rich soil hard as rock. Everywhere in the countryside, men and women in conical hats carry precious water in buckets balanced on bamboo poles across their shoulders, often for long distances. The government says more than 60 million people are affected, with more than 18 million people and 11 million livestock short of drinking water – numbers that grow daily.”

“Sudden shortages of economically vital sugar, rice, tea, and fresh flowers have driven up prices, and the drought zone’s rich hydroelectric resources are dwindling. State media this week said 90 percent of hydropower stations in the worst-hit province, Guizhou, were paralysed. This comes just as the government is struggling to rein in inflation and prevent it tripping up the country’s robust economic recovery. While the full economic damage remains to be seen, with the government already putting direct losses at nearly three billion dollars, the human impact is clear.”

Drought in 2009-2010 in Yunnan

Reporting from Qixingcun in Yunnan Province in late March 2010, Dan Martin wrote AFP, “In Yunnan alone, hundreds of reservoirs vital to rural communities have dried up or will do soon, state media have said. Tap water is cut off in many areas and illnesses have been reported as thirsty villagers drink unsafe reservoir water. The state media have been full of stark images of desperate villagers sitting amid the cracked beds of dried-up reservoirs. China has dealt for millennia with the alternating curses of drought and flood, but the severity of this dry spell is on everyone’s lips.” [Source: Dan Martin, AFP, March 29, 2010]

”Peasant farmer Dong Guicheng wakes up every morning hoping for rain, but each day a crippling drought instead brings more disappointment and desperation….Dong treks daily to a dwindling reservoir to fetch scarce water for his walnut and chestnut trees, which have seen almost no rain for half a year. His family has barely enough to drink, he hasn’t bathed for weeks, and Dong says the damage to his crops could cut his earnings by 80 percent this year.” “I am very worried,” Dong said, as he and his wife Dao Haiyan filled a rusty tank with water from the reservoir before carting it to their home two kilometers (one mile) away. “If there continues to be no rain I will have no income. The impact has been too big for words,” he said, shaking his fist skywards.

“I’m 64, and this is the driest I have ever seen it,” said Cai Yichang, a farmer who lives near the Yunnan city of Yiliang. Scanning sand-colored terraced fields that should be green, Cai has had to plant a smaller crop of onions and has been unable to plant his spring corn, a blow likely to halve his roughly 20,000 yuan (S$4,116) annual income. “My biggest fear is that if it continues to be so dry, the impact on the harvest will be severe,” he said, in between drags of tobacco on a large water pipe.

The government says it has rushed drinking water to the region, launched emergency water diversion projects and dug thousands of wells. But the impact on the ground has been as negligible as the rain, said Dong. “The government? They haven’t taken any measures. We just have to rely on ourselves to take the water to the fields,” said Dong, whose troubles are compounded by rising vegetable prices, which he said had more than doubled.

Affects of the Drought in Southwest China in 2009-2010

The soil on roughly 30,000 square miles of farmland was too dry to plant crops, the vice minister of water resources, Liu Ning, said last Wednesday. Around 24 million people were short of water. Agriculturallosses already total $3.5 billion.[Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, April 4, 2010]

As of April 2010, many areas have not had rain since at least October. In some places in Luliang County, about 70 miles east of Yunnan’s capital, Kunming, no rain has fallen since August. There many wells dried up completely and one family well that normally has 33 feet of water during the dry season only had a foot. Hong Kong’s major newspaper, The South China Morning Post, reported last month that many adults had left villages in Guangxi, and that many of those who remained behind were elderly residents and children who had difficulty finding drinking water.

The government stepped in by rationing drinking water to millions, digging 1,600 emergency wells and shooting silver iodide into the air in a marginally successful rainmaking effort. In mid-March, China’s premier, Wen Jiabao, made a three-day tour of Yunnan, including Luliang County, to pledge government help and urge new water-conservation efforts.

The drought’s effects also reached beyond China, stirring up tensions with its neighbors over energy and environmental concerns. China’s southern neighbors sharply questioned whether the drought’s effect on the Mekong River — at its lowest in a half-century — had been worsened by dams along its upper reaches, known as the Lancang, in western Yunnan. The hydroelectric dams there store water that otherwise would flow naturally in wet and dry seasons. The Chinese deny the charge and say that they released dammed water during this dry season to raise the Mekong’s level.

Environmentalists have raised other questions. Wang Yongchen, the senior environmental writer for China National Radio, asked in a March journal article in Beijing whether the reservoirs and rapid industrialization had permanently changed the climate in Yunnan. She said that the wholesale replacement of Yunnan’s forests with plantations — especially thirsty rubber and eucalyptus trees — may have lowered the region’s water table, dried the atmosphere and worsened water shortages.

Effect of Drought in Southwest China in 2009-2010 on Farmers

In Luliang County in Yunnan Province, farmers that sold their harvest of winter wheat for $585 in normal years were lucky to sell their meager crop for $30. A farmer named Huang Jianxue, told New York Times, “It’s only good for the pigs,” brushing perhaps six or eight wheat kernels from a stunted stalk that, in a normal year, would hold dozens. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, April 4, 2010]

Huang crops and animals were starved for water. He had to borrow money to send his 7-year-old son and 12-year-old daughter to school. Getting for work in the city was not an option as he can not read, and leaving his family would wipe out any chance to plant crops should the rains return. With virtually no money from the spring harvest, he said, his only plan to repay his debt is to kill the family pig and sell the meat.

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times,

“A several-hour tour of Luliang County on Sunday suggested the drought had struck in patchwork fashion. Residents said some reservoirs were dry basins of cracked mud, while others could be seen filled with water and surrounded by green crops.” In Shizikou village “verdant acres of rapeseed plants and other crops lined a dirty-looking river that had been tapped for irrigation.”

“But yards away from the river, 44-year-old Liu Hong said her entire wheat crop had grown only about a foot high before dying for lack of water, wiping out the $440 she had hoped to earn. Liu said she had been forced to borrow more than $700 from a local bank to send her two sons to high school. I don’t know what will happen if I can’t repay it, she said. And just down the road, 38-year-old Zhang Weixing’s crop of wendou, a type of pea used to make noodles, was so shrunken that his family was harvesting it to use as seeds rather than food. A crop that brought $440 in a normal year would be lucky to fetch $15 this time, he said.”

But as serious as the drought was, it affected only about 6 percent of China’s farmland and a tiny portion of its 1.3 billion people. The impact on inflation and food supplies in China as a whole were minimal.

Drought in Northern China in 2009

A severe drought struck parts of northern and central China in 2008 and 2009. The drought hit wheat growing areas in Henan and Anhui Provinces particularly hard. The government declared an emergency. Wheat prices rose and concerned were raised about out of work migrant workers returning home to find they can’t make a living at farming either.

The drought deprived 3.46 million people of adequate drinking water and affected 9.5 million hectares of farmland, An effort was made to bring irrigation water to agricultural areas deprived of water by diverting water from the Yangtze and Yellow Rivers. Irrigated water nourishes 60 percent of the winter wheat farmland and a third of all the farm land affected. In the Beijing area and elsewhere thousands of cloud seeding rockets and shells were fired to bring precipitation.

The worst drought in 60 years struck parts of northern China stretching from Jilin Province to Inner Mongolia in the summer of 2009, leaving 4.6 million people and 4.1 million head of livestock short of water.

The drought not only devastated China’s best wheat farmland, it also emptied the wells that provide clean water to industry and to millions of people. More than 18,000 square miles of farmland was labeled by the Chinese Agriculture Ministry. Northern China grows three-fifths of China’s crops and houses more than two-fifths of its people. [Source:Michael Wines, New York Times, February 24, 2009]

The drought occurred during the global economic crisis and peaked as millions of migrant workers who lost their jobs as a result of factory closings and construction shutdowns were returning from the cities to places where farming is the main source of income. Government officials were worried that water shortages and failed crops would raise the prospect of unrest among jobless migrants.

The national government increased spending on drought relief by about $44 million and announced plans to speed up the provision of annual grain and farm subsidies worth another $13 billion. Authorities also opened dam sluices, draining reservoirs toirrigate dry fields; dispatched water trucks to thousands of villages with dry wells; and bored hundreds of new wells. Newspapers reported the launching of thousands of rocket shells filled with silver iodide ro induce rain. Snow that fell on Drought-stricken Beijing were said to be the result of such efforts.

Effect of Drought in Northern China in 2009 on Farmers

Michael Wines wrote in the New York Times: “In the hamlet of Qiaobei in China’s wheat belt, a local farmer, Zheng Songxian, scrapes out a living growing winter wheat on a vest-pocket plot, a third of an acre carved out of a rocky hillside. He might have been expected to celebrate being offered the chance to till new land this winter. He did not.” [Source:Michael Wines, New York Times, February 24, 2009]

“Normally, the new land he was offered lies under more than 20 feet of water, part of the Luhun Reservoir in Henan Province. But this winter, Luhun has lost most of its water. And what was once lake bottom has become just another field of winter wheat, stunted for want of rain. Zheng, 50, stood in his field on a recent winter day, in one hand a shrunken wheat plant freshly pulled from the earth. I think I’m going to lose at least a third of my harvest this year, he said. If we don’t get rain before May, I won’t be able to harvest anything.”

“Zheng said his wheat was usually a foot tall by mid-February. But this year his field more resembled a suburban lawn in need of mowing, with clumps of wheat barely two inches high. Irrigation for such a small plot, he said, is too costly. We have a well up the hill, he said, but you have to pay 50 yuan every time you pump water, and you need to do it three times before you can harvest. The total of 150 yuan would be more than $20. So Zheng is hoping for rain, and counting on his two sons and daughter, who have jobs in nearby towns, to make up the money lost from crop failure.”

“In a neighboring village of 1,900, Zhailing…wells already strained by falling groundwater levels have effectively run dry, and many farmers have written off their wheat. Even regular day water is not guaranteed. How can we talk about anything for our crops? said Shi Shegan, the Communist Party secretary for the village.”

“The county-level chief of local drought-relief efforts, Gong Xinzhen, is determinedly upbeat about the situation. The county has bought 100 pumps to draw water from streams and wells, he said, and workers have handed out $15,000 worth of plastic bags for citizens to haul water from distant taps. Seven trucks are hauling water to communities like Zhailing where water has run out. Shi applauds the government’s hard work. But he also notes that when his village was built 14 years ago, one could sink a new well and haul water up by the bucketful. Now, he said, wells sunk 100 feet deep get mere trickles and can be tapped only once or twice a day.”

Winter Drought in Northern China in 2010-2011

The winter of 2010-2011 was the driest in perhaps 200 years in parts of China, which is the world’s largest wheat producer. This prompted worries that China might need to increase sharply its usually modest wheat imports, at a time when world food prices were already surging. Supplies were tight after bad weather in other producers, including Russia and Australia. Beijing launched a $1 billion emergency campaign of cloud-seeding and expanded irrigation.

Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times, “By January 2011, around 2.2 million people were facing water shortages as a result of droughts in southern, eastern and central China. Winter in China’s wheat belt is usually fairly dry. But this winter was so dry that it provoked considerable concern, from government offices in Beijing to the grain markets of Chicago. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, March 7, 2011]

“Some of the driest areas are close to Beijing, which has had no appreciable precipitation since Oct. 23, although there were brief snow flurries on Dec. 29. If the drought lasts 11 more days it will match one in the winter of 1970-71 as the longest since modern record keeping started in 1951, according to government meteorologists…In some places fields so dry large cracks appeared in the dirt. Particularly hard hit have been Hebei Province, which is next to Beijing…The dirt in farmers’ fields has become bone dry and is easily lifted by breezes, coating trees and houses in fine dust.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, February 3, 2011]

The U.N. food agency issued a rare “special alert — on Feb. 8 warning of the drought’s effects on the wheat crop and even on drinking water for people and livestock. Wheat futures in Chicago, already high because of extreme heat last summer in Russia, surged even higher when the food agency issued its alert, jumping 2 percent in a day. On Monday, wheat prices edged down 0.3 percent in early trading after word spread of China’s recent damp weather.

Drought Fuels Inflation and Has Global Implications

The severe drought in northern fueled inflation and alarming China’s leaders. Keith Bradsher wrote in the New York Times, “President Hu Jintao and Prime Minister Wen Jiabao separately toured drought-stricken regions and have called for “all-out efforts” to address the effects of water shortages on agriculture…Rising food prices were a problem even before the drought began, prompting the government to impose a wide range of price controls in mid-November. The winter wheat crop has been parched since then in northern China while unusually widespread frost has hurt the vegetable crop in southern China. [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, February 3, 2011]

“Food prices have been rising around the world, a result of weather problems in many countries, like the unusual heat wave in Russia last summer. High food prices have been among the many reasons for protests in Egypt and elsewhere in the Arab world. But even a prolonged drought in China appears highly unlikely to cause acute food shortages. China has spent years accumulating very large government reserves of grain and also has $2.85 trillion in foreign exchange reserves, giving it virtually unlimited ability to import food as long as major grain producers do not limit exports.”

“When commodity prices last surged in 2007 and 2008, however, at least 29 countries sharply curbed food exports in attempts to prevent domestic food prices from rising as quickly as world prices. And if China does become a large importer of wheat — it imports a lot of soybeans but tries to be essentially self-sufficient in rice and other grains for national security reasons — then it could push up world prices and make it harder for poor countries to afford food imports. Higher food and energy prices are spreading to other parts of China’s economy, contributing to broader inflation. Prices rose 4.6 percent in 2010, according to the consumer price index. The government has cushioned the effects of rising food prices by encouraging provinces and cities to sharply raise the minimum wage, which has been climbing 18 percent a year in Guangdong Province, in southern China.

“Accelerating inflation in China is starting to show up in the prices that American companies pay for imports from China. After years of showing little change, a United States Bureau of Labor Statistics index of average import prices suddenly jumped 0.3 percent from September to October, then jumped the same amount in November and again in December.”

In the end Rain and snow during late February and early March ” together with a huge irrigation effort, “saved much of the wheat crop in northern China from drought, Chinese and international agricultural and meteorological experts said…Days of snow and rain across the heart of China’s wheat belt in northern Henan and western Shandong provinces…The precipitation arrived at just the right moment, experts said, as vulnerable wheat planted last autumn was coming out its winter dormancy and needed to grow or it would die.” [Source: Keith Bradsher, New York Times, March 7, 2011]

Yangtze Delta Drought in 2011

On the drought that struck central China in the winter and spring of 2011, Jonathan Watts wrote in The Guardian, it is the — worst drought that parts of the Yangtze delta have experienced for more than 100 years…

“Even for a country that is used to drought, this year’s arid spell has been shocking because of its duration and location: the Yangtze region is usually considered one of the lushest in China. But Asia’s greatest river is shrinking and shallowing, along with many of the lakes around it. Shanghai is in its longest dry spell for 138 years, according to People’s Daily. Further upstream, Hunan is suffering the worst drought since 1910, affecting water supplies for 1.1 million people and 157 urban areas.”[Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, June 1, 2011]

“Television bulletins and newspapers are filled with images of dead fish, stranded ships and dry river beds. Hydropower production has been slashed and vast swaths of paddy fields are parched. The Three Gorges dam has been forced to cut hydropower generation and open its sluice gates to provide more water to downstream areas.

Recent cloudbursts — some precipitated by weather-modifying techniques — have raised hopes that the rainy season may finally have arrived. But the China Meteorological Administration forecasts a short, sharp — and possibly dangerous — flood season, amid a long, hot summer.

Another problem: “China is running out of cloud-seeding shells after pounding the skies with a massive barrage to ease the Yangtze delta drought. One of the country’s biggest manufacturers of the weather-modifying ordnance said its warehouses were empty despite raising production by 30 percent , operating on weekends and adding two hours to shift times.

Jiangxi Gangsi is one of the nation’s biggest makers of cloud-seeding shells. Company managers told the Guardian that they have struggled to meet a surge of demand during an unusually hot, dry spring. “There is demand but not enough supply. This year is special,” said Gu Jiangjun, a sales manager. “We normally produce 3,000 shells a month but now we are aiming for 4,000 to 5,000.” Agency officials encouraged local governments to make continued use of weather-modifying techniques. “We attach great importance to artificial rainfall in the effort to ease the drought,” said the administration’s vice director, Chen Zhenlin.

Droughts in the 2020s

In December 2021, China’s major southern cities Guangzhou and Shenzhen warned of impending severe water shortages lasting into next spring as the East River, a tributary of Guangdong’s Pearl River, was hit by Guangdong province’s most severe drought in decades. Reuters reported: Authorities in both cities are asking citizens to reduce water consumption, with rainfall between January to October this year down by a quarter compared to average levels over the last decade. The inflow of water into the East River Basin, a major supply of water for both cities, was around 50-60 percent its usual level. The company in charge of Guangzhou’s water supply is taking emergency measures to deal with increased salt tides, where the water supply becomes increasingly saline due to a lack of fresh water, it said. Hong Kong also imports much of its water from the East River. [Source: Reuters, December 8 2021]

In 2020, Yunnan Province and the Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau in southwest China experienced its worst drought in a decades, affecting more around 1.5 million people. Xinhua reported: As of April 15, 1.48 million people and 417,300 large domestic animals faced drinking water shortage, and 306,667 hectares of crops were damaged, according to the provincial water conservancy department. Some 100 rivers in the province were cut off, 180 reservoirs dried up, and 140 irrigation wells had an insufficient water supply, figures of the department showed. [Source: CGTN, Xinhua News Agency, April 18, 2020]

The Yunnan-Guizhou Plateau saw an uneven and lesser amount of precipitation in 2019 and 2020. In the two days of March 29 to 30, there had been seven cases of forest fires in Yunnan Province. The province poured 546 million yuan (around 77.1 million U.S. dollars) in drought relief, mobilizing 1.13 million people and 131,100 water-loaded vehicles to irrigate the farmland and providing drinking water to thirsty people and livestock.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Featured image: Drought-burned trees / Image Sources: Gary Braasch, Xinhua, ESWN environmental news