Drone Warfare: Barack Obama’s Idea of a “Just War”

by Prof. Tobias L. Winright and Prof. Mark J. Allman

This is an edited version of an article by US Catholic theologians Tobias L. Winright and Mark J. Allman that first appeared in the 18th August 2012 edition of the international Catholic weekly, The Tablet (www.thetablet.co.uk) as ‘Obama’s drone wars: a case to answer. Recalling that Barack Obama spelt out his commitment to the just war tradition at the outset of his presidency, Winright and Allman, reflect on whether the growing use of armed drones is in fact compatible with the just war tradition. Reproduced by kind permission of the publishers.

Every other week, US President Barack Obama hosts a meeting at which he makes the final decision on which terror suspects should be executed by unmanned planes or drones. At these biweekly “Terror Tuesday” meetings, the President personally reviews, through PowerPoint presentations, terror suspects who are nominated for the “kill list”.

In Pakistan alone, between January 2009 and September 2011, American drones launched more than 280 strikes that killed 2,103 people, a figure that includes 348 civilians. The growing use of unmanned vehicles in warfare by America, Britain and elsewhere has provoked a passionate debate about whether their deployment is compatible with the “just war” tradition, which holds that in order for violent combat to be justified it must meet certain criteria. A senior State Department lawyer, Jeh C. Johnson, has expressed his doubts. “If I were Catholic, I’d have to go to confession,” said Johnson after watching on a video screen a US Navy strike in al-Majala, Yemen, on 17 December 2009. Saleh Mohammed al-Anbouri, a militant with links to al-Qaeda, was the intended target. In addition to his death, the cruise missile killed 41 civilians, including 22 children.

St Ambrose (c. AD 340-397) would probably have agreed with Johnson. Ambrose, along with his protégé, Augustine, understood just war reasoning not merely as a way to justify going to war but as a means for keeping it within certain moral parameters, even on the part of rulers. Church tradition, like international law, holds that moral and legal rules should govern warfare. Even if most nations fail to adhere to it, they often invoke the just war tradition’s criteria to justify their actions and, in so doing, open themselves to moral evaluation of their use of military force.

In his Nobel Peace Prize speech in 2010, President Obama spoke about how the just war tradition arose in an effort to “regulate the destructive power of war”. He noted that just war historically had been “rarely observed”, especially given the “capacity of human beings to think up new ways to kill one another”. Nevertheless, he added, “an architecture” had been constructed over the last several decades “to govern the waging of war … to protect human rights, prevent genocide, and restrict the most dangerous weapons”. Terrorism and other threats had caused this scaffolding to buckle, requiring us, “to think in new ways about the notions of just war and the imperatives of a just peace”.

“By reducing the risks and costs of war, the use of UAVs and precision weapons may actually encourage more bellicosity and longer war.”

Sarah Kreps and John Kaag

Even so, he avowed that “all nations – strong and weak alike – must adhere to the standards that govern the use of force.” Although enemies may not abide by these rules, the President pledged that the US would bind itself to “certain rules of conduct,” something that “makes us different from those whom we fight”.

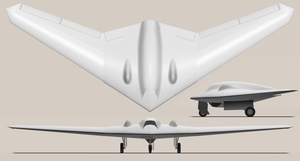

Has Obama sacrificed these ideals on the altar of obligation? He is now conducting wars of choice in six countries, including Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia. While the use of cruise missiles has decreased, these wars are increasingly being prosecuted through the use of drones, or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) as the military calls them.

One can see why Obama has been seduced by them; they are inexpensive and effective. Costing between 5 – 10 per cent of an F-16 fighter jet, they are expendable financially, and because they have no pilot when one is shot down, the political price back home is minimal.

Able to circle a target undetected for hours, UAV pilots can wait until civilians are away from the target to minimise civilian deaths. According to Obama’s top counter-terrorism aide, John O. Brennan, the US has “worked to refine, clarify and strengthen” the “rigorous standards and process of review” for its use of UAVs, so that targeted strikes conform to principles such as distinction) and proportionality. And the data shows that the civilian casualty rate is dropping.

Ethicists are not in complete agreement about drones, although most have expressed critical concerns about them. Catholic intellectual Robert P. George has written in the ecumenical journal First Things that “the use of drones is not, in my opinion, inherently immoral in otherwise justifiable military operations; but the risks of death and other grave harms to non-combatants are substantial and certainly complicate the picture for any policymaker who is serious about the moral requirements for the justified use of military force”.

The editors of the Jesuit magazine America have highlighted several legal and ethical concerns that need to be addressed in connection with drones, including the President’s problematic direct role in approving targets; the shift towards considering the presence of any fighting-age men as a “signature” of terrorist activity and therefore a valid target; the extrajudicial killing rather than the capture of suspects; and the ability of drones to penetrate the territory of nations with whom the US is not at war, thereby playing “havoc with traditional principles of sovereignty and non-interference”.

We share these concerns and raise several questions that have not received sufficient attention. First, on whether UAVs are inherently immoral, ethicists in the past, such as Methodist Paul Ramsey and, more recently, Oliver O’Donovan, have noted that the morality of a weapon depends on why it was made and how it is used. O’Donovan has observed that “instruments are apparently adaptable to different ways of acting”. A surgeon’s scalpel could be used to commit murder, and a pirate’s cutlass could be used to perform a surgical operation to save someone’s life.

Claims that UAVs minimise collateral damage is unverifiable at present because of the creative accounting by the US, which counts all military-aged males killed in drone strikes as combatants. According to O’Donovan, the guilty – and thus legitimate – targets are those who are directly and materially cooperating in the doing of wrong by their nation or, we would add, their terrorist group. This includes, but is not limited to, combatants. Direct material cooperation in wrongdoing can include politicians, mechanics, truck drivers and others who are not in uniform; the reverse side of this is that doctors, chefs and lawyers wearing a uniform are not necessarily combatants.

The distinction is not always clear, and O’Donovan acknowledges that drawing the line is difficult. But he adds: “Yet while we puzzle over the twilight cases, we cannot overlook the difference between day and night: a soldier in his tank is a combatant, his wife and children in an air-raid shelter are non-combatants.” The distinction, in short, is not impossible to make and to observe. The Obama Administration’s expansion of who is considered a combatant – all military-aged males killed in UAV strikes – goes too far into the grey twilight zone where non-combatant immunity no longer has teeth.

Then there is the question of authority: by what right does the US carry out targeted killings on foreign soil? Even if the host country grants permission, does it possess the right to allow other nations to kill its citizens, or, as in the case of Anwar al-Awlaki and Samir Khan, US citizens who had not been charged with any crimes but were killed in a UAV strike in Yemen last September? Although pre-emptive strikes are permitted in the just war tradition in the face of a grave and imminent threat, these targeted killings by UAVs may more closely resemble the death penalty, though without due process – a practice that the Catholic Church and most of the international community now morally condemns, even if it is done with due process.

Defenders of UAVs argue that they are more humane than conventional warfare. But this can be a false comparison, for the choice facing military leaders is not necessarily between a drone strike and conventional tactics (such as a cruise missile strike or special operations forces); the choice may be between a drone strike or no strike at all.

Technology makes the option available. As Sarah Kreps, of Cornell University, and John Kaag, of the University of Massachusetts Lowell, who have written extensively on the morality and legality of UAVs, point out: “Instead of the ends of a war determining the appropriate means … the means of modern warfare are determining objectives.” They warn that “by reducing the risks and costs of war, the use of UAVs and precision weapons may actually encourage more bellicosity and longer war.” Because drones are cheap and effective, they thrust us into a perpetual state of war, thereby making meaningless the just war requirement that war be a last resort.

UAVs neither allow for surrender nor account for cases of mistaken identity. According to the Geneva Conventions, when an individual lays down his arms, he becomes the responsibility of the one who captures him and is no longer a legitimate target. While other air strikes also lack this ability, the crucial difference is that drone pilots can see (in real time) the activity of the target, but lack the ability to take the person into custody. In short, UAV pilots cannot honour the flag of surrender.

Finally, UAV operators often operate thousands of miles from the battle zone. This widens the field of battle to include the home front and thereby threatens civilians who live alongside UAV operators. Although some supporters of the use of drones might say that terrorists have already attacked and continue to threaten the American homeland, the use of drones against terrorist threats elsewhere opens the door for further blowback in the US. Proportionality requires us to consider both the short- and long-term consequences of using a particular weapon.

Sometimes, just war requires saying no to using certain weapons, even if it puts us at greater risk. Of course, such a stance requires, as the US theologian and writer Daniel M. Bell Jr observes, a certain kind of character that includes virtues such as courage and temperance.

Tobias L. Winright is associate professor of theological studies at St Louis University, Missouri, and Mark J. Allman is professor of religious and theological studies at Merrimack College, Massachusetts. They co-authored After the Smoke Clears: the just war tradition and post war justice (Orbis Books, 2010).