Dr. Rosalie Bertell: Zero Tolerance for the Destructive Power of War. Illuminating the Path to Peace

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

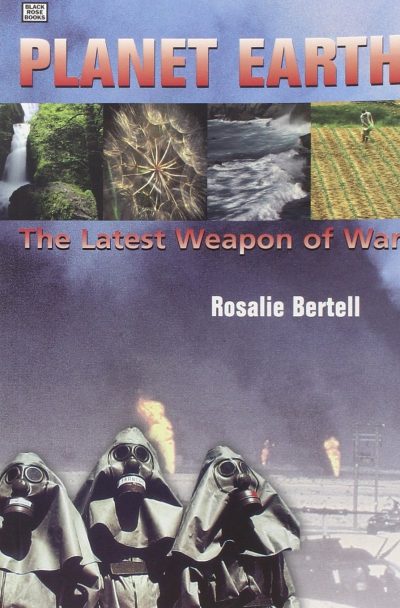

This is an excerpt from Dr. Rosalie Bertell’s book entitled Planet Earth:

The Latest Weapon of War.

*

This search into our past has admittedly been depressing….

There appear to be two paths towards global stabilization of population and resource:

- the first would use force, and violence, to reduce populations and limit consumption;

- the second would propose reducing the felt need for population increase through fulfilling basic survival requirements, providing security from violence, and increasing resource productivity.

This second path has many supporters…. Can we find ways of achieving greater eco-efficiency and eco-sufficiency, peace and rule by law? Can we accomplish an equitable distribution of goods and services both within and between nations?

I believe that there are clear steps we can take. As in most serious illnesses, there is emergency treatment, followed by a long recovery period, counting on nature’s own restorative power. In my view the emergency action we must take is to terminate the military. Both this and the long process of behavioural modification rest on the human ability to change.

Part III: Rethinking Security,

Chapter VI: Military Security in the New Millennium

The problems we face at the beginning of the twenty-first century involve interconnected issues of militarism, economics, social policy and the environment. Global consumption of resources is exceeding Earth’s restorative capacity by at least 33 per cent. War and the preparation for war drastically reduce the store of these resources still further, leading to a self-perpetuating cycle in which competition for raw materials leads to further conflict. This means that global survival requires a zero tolerance policy for the destructive power of war.

However, I recognize that exposing the extremes of today’s military and outlining the crisis in resources will only bring about change if we also tackle the question of security. Popular support for the military comes from fear, and that fear is based on hundreds of years of recorded history. We feel that we must have weapons to protect ourselves from the weapons of the enemy. This fear legitimizes the development and stockpiling of new weapons and results in the election of public officials who will not hesitate to use violence. This in turn attracts the warrior to public office and reinforces his or her belief that military might is the best assurance of security. If the public were convinced that there were real, viable alternatives to war, such figures would lose their mandate.

Therefore, it is vital that a new concept of security is devised, which puts Earth and its inhabitants first. The old paradigm of security protects wealth, financial investment and privilege through the threat and use of violence. The new concept embraces a more egalitarian vision, prioritizing people, human rights, and the health of the environment. Security itself is not being abandoned; it is just being achieved through the protection and responsible stewardship of the Earth. I would call this emerging new vision ‘ecological security’. Such a shift in focus requires a complex, multi-faceted approach to resource protection and distribution, to conflict resolution and the policing of the natural world. In Chapter 7, I will outline some of the directions we might take towards achieving these goals. But in order to do this, we must first challenge the belief that military force is a necessary evil.

Working for Change, Altering the Core Belief

Social change always follows a period when a core belief is identified and rejected. As support and awareness of this new way of thinking grows, the political climate changes and the old way of doing things is no longer acceptable. That is the lesson we learn from history. I believe, for example, that the vast social changes of the 1950s and 1960s came about when people began to challenge the idea that everyone should conform to socially imposed patterns of behaviour. This shift resulted in a new understanding of human and civil rights, with a focus on the freedom of the individual and an acceptance of racial, religious and sexual diversity.

Once a core belief is overturned, related changes spread under their own impetus. In the 1950s and 1960s we saw the growth of movements for civil rights, women’s rights, black power and gay rights. Consciousness-raising in turn yields changes in legislation, social behaviour, policy, and even language. More recently we have seen the recognition of the rights of the child, the movement against child soldiers, and animal rights groups.

There will always be those who resist change—in the 1960s, the rejection of socially imposed behaviour led to fears of social chaos. But we are quick to monitor when things go ‘too far’ and we adjust our beliefs accordingly. So whilst we recognize the freedom of the individual, for example, this does not mean that we tolerate them violating the rights of another. Self-correction and adjustment following the rejection of a core belief is a vital part of the process.

The core belief being challenged today is that military power provides security. There exists more than enough evidence to show this belief is untrue….

Lobbying for Change

The first step in change is the conviction that change is needed. This could be said to be the theoretical stage based on observation and reassessment. The next step is practical, when people come together to exchange ideas and information and to lobby for social transformation. What we find in reality is that these two processes occur simultaneously – discussion gives rise to groups of like-minded people wo engage in further analysis.

It is clear that the multi-faceted problems outlined in this book will require a multi-faceted solution. No one person or organisation will have the wisdom needed to deal with all of the issues that must be addressed. Those working for peace, economic justice, social equity and environmental integrity must all stay connected, sharing their ideas and insight. ‘Staying connected’ in such a grandiose project will never mean total agreement in everything, rather a constant cycle of communication, action, feedback and evaluation. Honest dialogue about successes and failures is a protection against major mistakes during alternative policy development.

The good thing about such a complex range of problems is that the process of change can engage a wide variety of talents. Everyone should be able to find a comfortable niche where he or she can be useful and appreciated….

Once an individual has identified the skills they have and the issue they want to address, they need to find a suitable group of like-minded people with whom they can work and from whom they can derive support…. The most important thing is that these efforts must be cooperative and not competitive. The way we organise for reform is part of the solution for healing. If confrontation and competition have led to excessive greed and violence, then we require the opposite skills to rectify the imbalance.

Phasing Out the Military

So how would we actually go about bringing an end to the military? The first and most important requirement is that the military come under civilian control; then we must look at effective disarmament and the redirection of military resources, including human resources, towards more humanitarian aims; finally we must seek alternative means of resolving conflict. We also need to bring the research community into this question so that disarmament becomes a long-term reality.

Control of the Military

Many people were shocked when NATO decided to bomb Kosovo on its own authority. If NATO or some other coalition outside of the United Nations can dictate military policy then the chances of promoting a peaceful solution to any crisis are seriously damaged. There is more security for the public when international actions are based on decisions made by a civilian authority and are backed by the rule of law…. When power is dispersed, it is less likely to be abused.

However, it is clear that the goal of change is not just civilian supervision of the military but the dismantling of the military altogether. This change will not be easy. No country is going to terminate its military forces unless it can be absolutely sure that other countries are doing the same—the fear of being vulnerable to attack would be much too strong.

Disbanding the Military

The United Nations, with the assistance of NGOs like SIPRI, has been tabulating military expenditure and arms race transfers for many years. Enough data is now available to successfully monitor a freeze in military spending….

An alternative suggestion is to redefine the military’s job description. After all, they are supposed to work for us and in our name. Proposals include using military personnel for civilian assistance in ecological crises such as floods or volcanic eruptions. They could also carry out genuine peacekeeping, with new nonviolent training programmes and the development of conflict resolution skills. Imagine unarmed peacekeepers trained in the art of diplomacy. When the option of war is not available, people are forced to think about the many possible but untried responses….

Some members, or former members, of the military have begun to question the relevance of their activities, such as the Retired Generals Opposed to Nuclear War, who have been so vocal in support of eliminating all nuclear weapons….

Of course not everyone in the military takes such an enlightened view, and there is bound to be military resistance to the new concept of security. I regard NATO as one of the greatest obstacles to general disarmament in Europe and North America….

War itself needs to be banned. There are no disputes between nations that cannot now be skills, we should be heading towards an exciting new era of real diplomacy. Indeed even after a war negotiations are necessary before ‘peace’ is established. The main accomplishment of the violence is to force concessions at the negotiating table, but because a war influences the ‘freedom’ of the loser, post-war negotiations are notoriously unjust. Often this sets the stage for the next war—one reason perhaps why the Second World War followed on so swiftly from the First. With the Chemical Weapons Convention, banning chemical warfare, which came into force on 29 April 2000, and review of nuclear weapons reduction on the United Nations agenda for the same year, it seems to be the opportune moment to push this nonviolent agenda.

Two Success Stories

Landmines

One of the most effective citizen initiatives in recent history has been the global ban on landmines. Jody Williams, who spearheaded the International Coalition to Ban Landmines, won a Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts.

The United Nations estimates that landmines kill or maim about 25,000 people every year. The problem is immense, with an estimated 60 to 70 million mines deployed around the world. Africa is the most heavily mined, with as many as 30 million devices in 18 countries.

Removing landmines is a difficult, slow, and nerve-racking job. Greg Ainsley, a 21-year-old from Edmonton, Canada, explains how it is done….

The peace movement, largely through the efforts of women, has been working to ban landmines since the early 1990s and in 1994 the International Red Cross added its voice to the protest. The campaign enlisted the help of Diana, Princess of Wales, who used her celebrity to bring the humanitarian dimension of the problem to the public, emphasizing the extraordinary proportion of children killed or maimed for life. In October 1996, the Canadian government convened a meeting in Ottawa of 50 governments favourable to a complete ban, and in December 1997 some 90 countries signed a special treaty drafted in Oslo. Britain and France, major exporters of landmines, agreed to the ban, but the US decided not to sign because it wanted to use the weapons in the demilitarised zone of Korea. Other non-signing producers of landmines were Russia, China, India, Pakistan and Israel….

The treaty does not tackle the problem of the 80 million mines already planted, nor does it prohibit mines designed to blow up vehicles or disable tanks. Nevertheless, it is one small step towards phasing out the violence of war. It clearly places great value on individual lives, especially those of women and children, and it has the added benefit of protecting agricultural land that becomes useless when strewn with bombs. The ban on landmines provides a model of cooperation between non-governmental organisations, with widespread grassroots support, and gives encouragement for future initiatives.

Nuclear Weapons

The World Court Project

A second successful initiative was the World Court Project, an idea strongly promoted by Commander Robert Green, a retired British navy officer. According to Green, although there are prohibitions against weapons of mass destruction, military personnel are told that nuclear weapons have never been outlawed. Quoting from the US Military Manual: ‘The use of atomic weapons cannot be regarded as a violation of international law in the absence of any customary law or convention restricting their use.’ As a commander of ships carrying nuclear warheads, Green has always been bothered by this. Since both the US and UK military manuals require personnel to adhere to principles of international law relating to warfare, Green reasoned that a declaration of the International Court of Justice would go a long way towards eliminating those weapons and supporting military personnel who refused to use them.

Retired Commander Green spoke out publicly in Europe and North America, in support of the International Court of Justice review. General Charles Homer, head of the US Space Command, also spoke in favour of abolishing nuclear weapons. These individuals and others, such as international law expert Richard Falk, gave impetus to popular support for the initiative. In fact, the World Court motion was accompanied by intense civilian action through a coalition of international peace groups such as the International Peace Bureau, the War and Peace Foundation, International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom and the International Association of Lawyers for the Abolition of Nuclear Arms. This coalition activity focused on a provision of the World Court constitution that had never been used before. According to this provision, the judges are obliged to take into account ‘the dictates of public conscience’. For this reason over a hundred million individuals sent in a declaration of conscience, stating:

It is my deeply held conscientious belief that nuclear weapons are abhorrent and morally wrong. I therefore support the initiative to request an advisory opinion from the World Court on the legality of nuclear weapons.

After receiving briefs from various governments and these public statements of conscience, The International Court of Justice issued a Communique in July 1996 stating that:

THE COURT unanimously DECIDES a threat or use of force by means of nuclear weapons that is contrary to Article 2, paragraph 4, of the United Nations Charter and that fails to meet all the requirements of Article 51, is UNLAWFUL….

Unanimously, DECIDES, a threat or use of nuclear weapons should also be compatible with the requirements of the international law applicable in armed conflict particularly those of the principles and rules of international humanitarian law, as well as specific obligations under treaties and other undertakings which expressly deal with nuclear weapons…

By seven votes to seven, it follows from the above mentioned requirements that the threat or use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law applicable in armed conflict, and in particular the principles and rules of humanitarian law. However, in view of the current state of international law, and of the elements of fact at its disposal, the Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in extreme circumstances of self-defense, in which the very survival of the State would be at stake. [author’s emphasis]

Unanimously, DECIDED there exists an obligation to pursue in good faith and bring to a conclusion negotiations leading to nuclear disarmament in all its aspects under strict and effective international control.

[The International Court of Justice, Peace Palace, The Hague, Communique No. 96/23, 8 July 1996]

It is interesting that the court’s support for nuclear disarmament was unanimous whilst it was split on the section dealing with ‘extreme circumstances’. Observers who were actually present at the court say that this compound statement was really a political ploy so that the court did not have to deal with each part of the resolution separately….

Overall, however, the outcome was encouraging. It demonstrated that there was some support within the military for placing limits on violence, especially for banning nuclear weapons. Moreover, it demonstrated that ordinary citizens could successfully engage international organisations like the World Court. It was heartening to see that both governments and the public respected this legal intervention to limit weapons of war. This second success story, like the first, involved collaboration between individuals, governments, and international organisations.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Dr. Sister Rosalie Bertell, Grey Nun of the Sacred Heart, 1929-2012

Hildegard Bechler is a community activist who organized a province-wide speaking tour for Dr. Bertell, a leading expert (in 1978) on the health impacts of low-level ionizing radiation. Rosalie’s new information galvanized public opinion in support of citizens working cooperatively for 15 years to successfully prevent nuclear reactors and uranium mining in British Columbia, Canada.