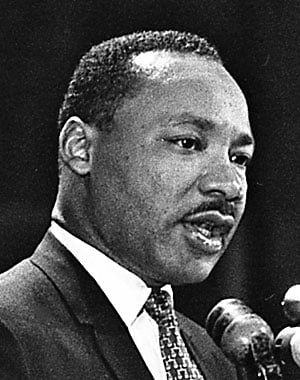

Dr. Martin Luther King’s Legacy: Linking the Civil Rights Movement to the Struggle Against War and Poverty

Five decades ago the SCLC leader took a firm position in opposition to the United States occupation of Vietnam

On April 4, 1967, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. took to the pulpit at Riverside Church in New York City to denounce the escalating United States imperialist intervention in Vietnam.

Several days before on March 25, King along with pediatrician Dr. Benjamin Spock, who at the time was the co-chairman of the National Committee for Sane Nuclear Policy, led a mass demonstration in Chicago calling for the administration of the-then President Lyndon B. Johnson to enact an immediate ceasefire and withdrawal from Southeast Asia.

Marching also with King at the front of the demonstration was Al Raby of the Chicago Coordinating Committee of Community Organizations (CCCO), Jack Spiegel of the United Shoe Workers Union and Bernard Lee, an assistant to King in the local chapter of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). There were also members of the Veterans for Peace in Vietnam who walked alongside the others at the head of the manifestation which included thousands of people.

This was the first demonstration that King had participated in against the war. Earlier in an article published by the Chicago Defender in January 1967 King had expressed his evolving public position. Later in February he delivered an address at an antiwar conference held in Southern California sponsored by the Nation Magazine.

Although the SCLC leader had expressed reservations and even opposition to the escalating war in Vietnam since early 1965, he had refrained from participation in antiwar demonstrations and did not address the military intervention in a comprehensive fashion. For example, after he spoke at Howard University on March 2, 1965, he answered questions from the press where he stated that the war in Vietnam was accomplishing nothing and required negotiation.

Later at the national conference of the SCLC, he called for a halt to the bombing of North Vietnam and the empowering of the United Nations to proceed with negotiations for the cessation of hostilities. He said during his speech that “What is required is a small first step that may establish a new spirit of mutual confidence … a step capable of breaking the cycle of mistrust, violence and war.” (King Encyclopedia at Stanford University)

Nonetheless, his wife, Coretta Scott King, had been far ahead of him in regard to issues related to world peace. In 1962 she traveled to the Eighteen Nation Disarmament Conference held in Geneva, Switzerland as a delegate from the Women’s Strike for Peace. Later in 1965 Coretta Scott King spoke at two antiwar demonstrations on the Mall in Washington, D.C. and in New York at Madison Square Garden.

Before the SCLC came out in opposition to the Vietnam War, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) had issued a comprehensive statement in January 1966 drawing a correlation between the failure of the Johnson administration to guarantee the democratic rights of African Americans and the massive deployment of U.S. troops in Vietnam.

By 1967, demonstrations and rallies against the Vietnam War grew in their numbers and militancy. On April 15, 100,000 people marched from Central Park to the United Nations demanding an end to the war. Drs. King and Spock along with Stokely Carmichael (later known as Kwame Ture), the-then Chairman of SNCC, led the demonstration. In October of the same year there was a demonstration at the Pentagon which resulted in clashes with the police.

The growth of the antiwar movement coincided with the urban rebellions throughout the U.S. as well as unrest within the educational sector. Students and youth began to call for the removal of ROTC from high schools and college campuses along with the defunding of military research.

Civil Rights and Economic Justice

After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the struggle of the African American people shifted to the implementation of these legislative measures in the South and other regions of the country in the North and West. Independent political parties and mass initiatives were established such as the Lowndes County Freedom Organization (LCFO), the original Black Panther Party, in an effort to build substantive political power.

The resistance to independent political action by the state and federal governments after 1965 sparked urban rebellions in many cities from New York and Los Angeles to Chicago, Cleveland and Detroit. The emergence of urban rebellion as a tactic within the struggle for national liberation and equality alarmed the Johnson administration because it posed a direct challenge to its foreign policy. With African Americans serving in Vietnam disproportionate to their numbers within the overall population, any successful antiwar movement calling for a rejection of the draft and the desertion of troops from the frontlines would ensure a victory for the people of Southeast Asia.

In his speech in the aftermath of the March 25, 1967 demonstration in Chicago, King noted that:

“Poverty, urban problems and social progress generally are ignored when the guns of war become a national obsession. When it is not our security that is at stake, but questionable and vague commitments to reactionary regimes, values disintegrate into foolish and adolescent slogans.”

King then went on to say:

“America is a great nation, … [b]ut honesty impels me to admit that our power has often made us arrogant. We feel that our money can do anything. We arrogantly feel that we have some divine, messianic mission to police the whole world. We are arrogant in not allowing young nations to go through the same growing pains, turbulence and revolution that characterizes our history… We arm Negro soldiers to kill on foreign battlefields but offer little protection for their relatives from beatings and killings in our own South….”

(jofreeman.com/photos/KingAtChicago.html)

By late 1967, Dr. King announced that SCLC in alliance with other organizations from the Chicano, Native American and poor white communities, would launch a Poor People’s Campaign in Washington, D.C. Thousands were mobilized to enter the nation’s capital to occupy the city until legislative and administrative actions were taken to end poverty and economic inequality.

Prior to the beginning of the Poor People’s Campaign, King went to Memphis to support the sanitation workers strike which demanded recognition under the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). It was in Memphis that King called for a general strike in lieu of the resolution of the labor dispute.

King was assassinated on April 4, 1968 before the strike was settled. In response to his assassination rebellion erupted in approximately 125 cities across the U.S. including Washington, D.C., Baltimore, Pittsburgh and Chicago.

The Continuing Struggle Against National Oppression and Social Injustice

Since 1968, the problems of national oppression and economic inequality have worsened. Today unemployment and poverty remain major obstacles to the full realization of national liberation among the African American people and other people of color communities.

These problems however cannot be resolved under the capitalist system. The greater concentration of wealth among the ruling class mandates the general redistribution of resources from the small elite of exploiters to the majority of the working class and oppressed.

This social transformation of U.S. society will not come about through the goodwill of the ruling class. The workers, farmers and oppressed must be organized and mobilized outside of the framework of the two-party capitalist political system.

Therefore these are the challenges facing the present generation of youth. Consequently, a revolutionary party must be built that can speak and act in the interests of the exploited and oppressed in the U.S. in solidarity with the peoples of the world.