Dodging Silver Bullets: How Cloud Seeding Could Go Wrong

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

“We need more rain and we need it now. We need some divine intervention. That’s why I’m asking Utahns of all faiths to join me in a weekend of prayer.” —Utah Governor Spencer Cox

With water shortages in the American West continuing to worsen, policymakers are starting to recognize that incremental changes such as “avoiding long showers [and] fixing leaky faucets” will not be sufficient. During crises, “silver bullets”—promising but overly-simplistic technological solutions to complex problems—become increasingly appealing, despite the acknowledgement that no single technology or policy can address complex challenges like water shortages or climate change.

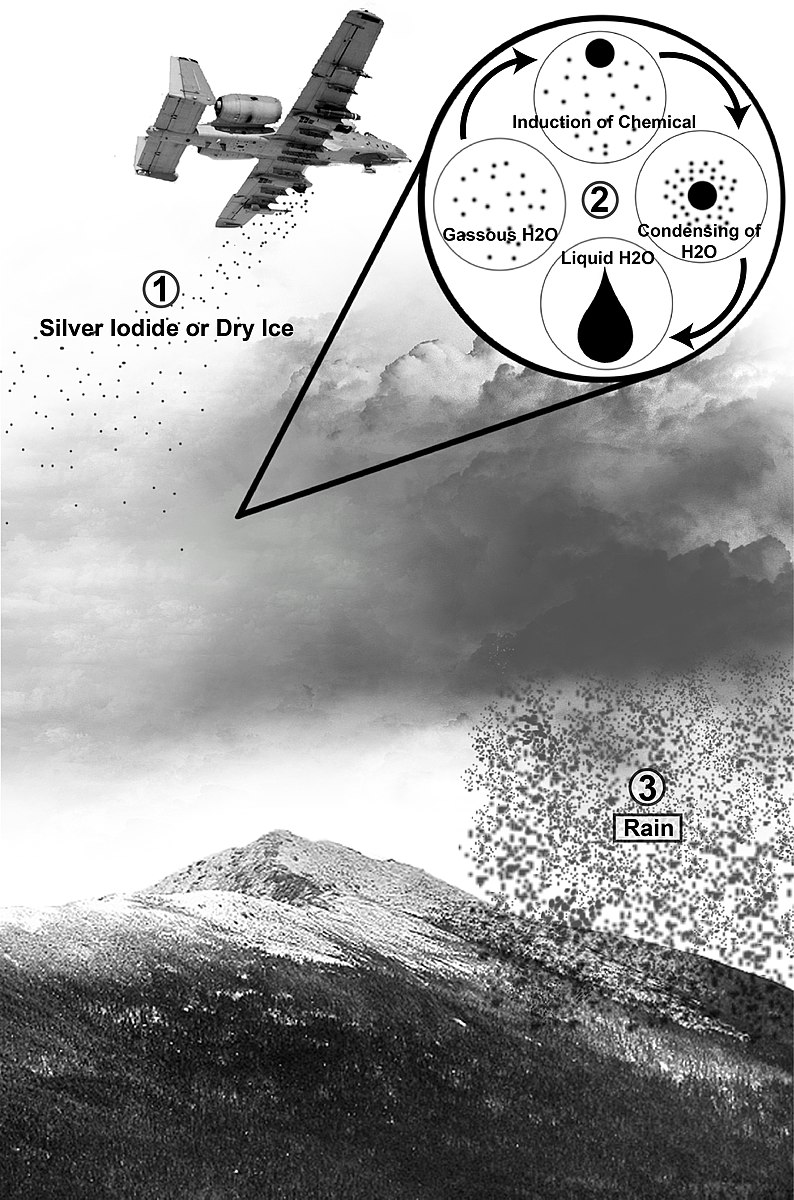

Cloud seeding is perhaps the ultimate silver bullet, in which literal silver in the form of silver iodide is infused into clouds, causing ice crystals to form and water to condense into rain or snow. Cloud seeding is a form of planned weather modification. Most commonly used to increase precipitation as a drought management technique, cloud seeding is also regularly used to clear fog in airports, fight forest fires, suppress hail, and even divert rainfall, as it was used, for example, during the 2008 Olympics in Beijing.

The promise of creating rain is highly appealing in the face of increasing water shortages and disruptions to water cycles exacerbated by climate change. While cloud seeding is not a new technology—the first experiments took place in the 1940s—it fell out of favor in the 1980s for being an “unacceptable ethical and environmental hazard.” It is now back on the policy agenda as a climate adaptation strategy. Idaho, Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and California have all expanded their cloud seeding operations in the past two years in response to the worsening drought. Despite its potential, the risks associated with cloud seeding are high, and there is significant danger that cloud seeding may do more harm than good.

“Human consequences.” As early as 1965, the National Science Foundation called for urgent social science research into the impacts of weather modification, stating, “If the developing techniques of weather and climate modification are to be used intelligently, the human consequences of deliberate or inadvertent intervention need to be anticipated before they are upon us.” But these issues continue to be under-explored. Compared to other forms of geoengineering that have received greater attention and generated morecontroversy—such as expanding research on solar geoengineering—policy discussions about the use (and misuse) of cloud seeding are lacking, even though it has been widely deployed.

How cloud seeding works (Image: Naomi E Tesla/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 4.0)

Although “controlling the weather” sounds futuristic, cloud seeding has a long history going back to 1946, when General Electric research laboratories caused snow to fall near Mount Greylock in Massachusetts. Since 2000, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which monitors cloud seeding operations in the United States, has recorded over 50 projects. These programs receive significant governmental funding. Utah, which has one of the largest cloud-seeding programs in the United States, spends up to $700,000 annually. (Bizarrely, given Utah’s robust cloud seeding programs, the acting director of the state’s Department of Natural Resource recently seemed to pitch cloud seeding as a new thing to try to save the Great Salt Lake.) China, India, the Russian Federation, Thailand, the United Arab Emirates, and the United States all have major ongoing research programs.

Policy frameworks regulating the use of cloud seeding exist but are incomplete. For example, each of the Western US states using cloud seeding to supplement natural snowpack has regulations on the appropriate time to conduct cloud seeding, as well as limits on when seeding can be done. These limits are meant to ensure that cloud seeding doesn’t cause flooding. However, broader governance systems designed to address potential risks posed by cloud seeding are not in place.

Without significant engagement with potential risks and unintended consequences, cloud seeding is likely to lead to maladaptation, or “action taken ostensibly to avoid or reduce vulnerability to climate change that impacts adversely on, or increases the vulnerability of other systems, sectors or social groups.”

“Empty promises.” Cloud seeding is emblematic of techno-optimism, or the belief that technological solutions and ingenuity can solve complex issues—an attitude deeply embedded in American political culture. Despite enthusiasm for cloud seeding, the evidence of its effectiveness is at best mixed. In the words of the World Meteorological Organization Expert Team on Weather Modification, “sometimes desperate activities are based on empty promises rather than sound science.”

In 2003, the National Academy of Sciences produced a study reporting a high degree of uncertainty regarding the efficacy of cloud seeding. Since then, numerous studies have been conducted, but the evidence is still inconclusive. A recent synthesis by the World Meteorological Organization concluded that increased precipitation ranged between zero and 20 percent, with the upper range representing conditions under which clouds were highly likely to form precipitation naturally. Particularly concerningly, it is widely acknowledged that cloud seeding is least likely to be effective during drought conditions, as clouds do not have moisture to release, and yet operations often continue during droughts, suggesting that the programs serve more of a political purpose than a climactic or meteorological one.

A new study based on an experiment in Idaho known as SNOWIE provided more promising results, but the authors emphasize that it is primarily through the long-term build-up of snowpack that cloud seeding can contribute to water management, and it is unlikely to work as a short-term solution. As the science of cloud seeding advances, the potential to demonstratively increase precipitation grows, but narrow discussions of the potential efficacy of the technology mask broader conversations about its long-term effectiveness.

Technological fixes can obscure deeper structural drivers of vulnerability like unsustainable water use and unequal distribution of access to water. Political and policy conversations about water use can conflict with strongly held values and beliefs. But unless such questions are front-and-center in policy debates, cloud seeding is likely to reinforce existing inequalities.

Evidence of the inability, or unwillingness of policymakers and the public to engage with these difficult questions is widespread. For example, real estate developers have proposed building at least four large surf lagoons in the Palm Springs desert region of California, despite persistent water shortages. Advocates argue that these “wave resorts” will replace golf courses that are even more water-intensive, but narratives of incremental improvements belie the need for transformational changes and illustrate the level of disconnect between current development patterns and the reality of water shortages.

Surf lagoons might not be any worse than water-guzzling golf courses, but are they really the best idea for water management in arid Palm Springs? (Photo: Visitor7/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0)

Adaptation in a political process and solutions must address the underlying power dynamics inherent in adaptation. Tensions between water use for agriculture and cities drive water shortages in the American West, and current policies incentivize agricultural use of water allocations even when this is not an efficient use of water. “Use it or lose it” water rights policies and lack of groundwater use limits have significantly greater impacts on water shortages than cloud seeding could ever have.

While there are no simple solutions to water policy in the American West, significant policy changes are needed and current discussions about where and how to seed clouds don’t tackle these complex challenges.

Redistributing risk. While cloud seeding is often described as “creating” rain, it can be more accurately described as moving rain from one location to another, and cloud seeding may simply redistribute risk. Cloud seeding condenses water that is already present in cloud formations. As such, some have argued that cloud seeding cannot impact hydrological cycles at a large scale. But the American Meteorological Society acknowledges that while there is currently no evidence of downwind impacts, these cannot be ruled out, and that “activities conducted for the benefit of some may have an undesirable impact on others.”

Despite claims of only local impacts, cloud seeding is already being coordinated at a regional scale across the Colorado River Basin. If adopted widely, cloud seeding could be used politically to deprive certain regions of rainfall (for example as a weapon of war), or to claim water that would otherwise be more widely distributed. These concerns are not hypothetical: in 2020 China announced its “Sky River Plan” to divert water vapor from the Yangtze River basin to the Yellow River basin, a cloud seeding initiative that would cover an area half the size of India. This raises large governance questions about how to ethically divide water and who controls the sky. Without clear policies, including international policy to address transboundary cases, it is likely that the most powerful actors will benefit at the expense of others.

Certain uncertainties. Proponents claim that there is little to no evidence of environmental or health harms stemming from cloud seeding. However, silver iodide, the chemical most commonly used to seed clouds is known to be toxic and is regulated under the Clean Water Act as a hazardous substance. Some studies suggest that the amount of chemicals used is small and the silver iodide is not biochemically available, rendering it ecologically harmless. However, other studies highlight the potential harms from bioaccumulation, particularly for aquatic life. They show that while overall levels of silver iodide are relatively low, they have exceeded health standards in areas with repeated exposure.

Precipitation resulting from cloud seeding can also have unintended consequences. For example, a study in the United Arab Emirates demonstrated that cloud seeding operations led to an increase in urban flooding. A deathly blizzard in China and severe flooding in the United Kingdom have also been linked to cloud seeding.

More broadly, the uncertainties that are widely acknowledged in the science of cloud seeding mean that potential harms are not well-understood. The World Meteorological Organization adopted guidelines in 2017 advising members not to perform weather modification activities without considering the high levels of uncertainty in effectiveness and potential harms involved.

Silver bullets are appealing because they present simple solutions to complex problems, but only by embracing complexity can leaders around the world ensure that cloud seeding doesn’t do more harm than good.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Laura Kuhl is an Assistant Professor of Public Policy and Urban Affairs and International Affairs. Her research examines climate adaptation and sustainable transitions in the United States and internationally. She is particularly interested in questions of power and equity in processes of transformation across multiple scales from individual decision-making to international policymaking. Current work focuses on climate finance, particularly adaptation finance, energy equity after crises, and transformational adaptation.

Featured image: The Great Salt Lake is currently just a third of its former size, exposing sediment full of toxic chemicals from the region’s mining history that—once dislodged and sent airborne—can turn into toxic dust storms. Utah officials have suggested solving the drought with cloud seeding—and prayer. (Photo: Brigitte Werner)