Did Globalization Drive Far-Right Electoral Success in European States From 1990-2020?

Introduction

Globalization – characterized by political and economic integration both among European Union (EU) member states and between the EU bloc and the world at large — has produced three observable domestic sociopolitical consequences in European states explored in this research. These include increased transnational immigration rates, the perceived loss of national/ cultural/ ethnic identity among the affected populations, and uneven distribution of economic benefits across social strata, which will be explored and measured in the literature review section of this study.

These three phenomena induced by globalization may have produced domestic political backlash from the populations affected by them. For whatever benefits globalization might confer, the process necessarily requires some concessions from nationalists who identify culturally and politically with the state and from the states themselves, which must surrender some degree of sovereign control over their economies and national borders. This research will examine whether “far-right” (defined herein) electoral success in France and Hungary from 1990-2020 is the result of popular domestic blowback against globalization and liberal ideology broadly. France and Hungary will serve as the case studies here, the results of which may be extrapolated and tested in the context of other European states in future studies.

The thesis tested in this research is that three factors (immigration to EU member states, perceived loss of national identity and sovereignty, and uneven distribution of economic benefits across social strata) resulted in increased electoral votes for “far-right” parties as a percentage of the total vote in France and Hungary from 1990-2020.

Literature review

The section on globalization contains a trio of subsections: globalization’s effects on inequality, globalization’s potential to undermine national sovereignty, and the inherent conflict between protectionist policies and globalization. The section on effects of globalization on domestic politics and populations in France and Hungary is likewise comprised of three subsections: transnational immigration, perceived loss of national/cultural/ethnic identity, and uneven distribution of economic benefits across economic strata.

Globalization

The integration of the function of the state into broader governing bodies at the regional and global levels is termed is a key feature of globalization – otherwise known as “transnationalism.” The Geneva Centre for Security Policy summarizes globalization as “a process that encompasses the causes, course, and consequences of transnational and transcultural integration of human and non-human activities.” (Carminati, 2017) Since the 19980s, “one of the most striking features of the international economy… has been the proliferation and intensification of regional trading agreements around the world.” (Hanson, 1998, pg. 55) Beyond the regional level, so-called “mega-regional” trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) and Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), which encompass huge swathes of the global economy, .have also proliferated in the increasingly globalized economy. (Gonzalez, 2016)

Globalization has impacted most of the world, including European Union (EU) member states. The EU was a post-WWII project to integrate Western Europe – and, later, after the collapse of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s, Eastern Europe. Prior to the advent of the European Union, the states of Europe existed in a realist anarchy at the international level in which economic competition had historically led to war. Per interdependence theory, of the neoliberal school of thought, offered as an alternative to realist conflict, transnational institutions that facilitate trade have the capacity to enhance cooperation between states and reduce the likelihood of war as a result. (Jervis, 1999, p. 62)

The initial iteration of the EU was the supranational European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), founded shortly after World War II which “pooled the coal and steel resources of six European countries: France, Germany, Italy, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg (BENELUX)” (Carleton, 2023) in order to control the German steel and coal industries. The main motivation for the creation of the ECSC was to prevent another outbreak of war on the continent by constraining Germany. The next big change in European integration came with the 1985 Schengen Agreement, which abolished internal borders within the EU to allow the free flow of people and capital across member states. The Schengen Agreement included the original six members of the ECSC plus Denmark, Ireland, the UK, Greece, Portugal, and Spain. (Traynor, 2016)

In 2004, a major expansion of the EU welcomed member states from Eastern and Central Europe that had once been behind the Iron Curtain before the Soviet Union’s collapse in the early 1990s. With such a huge block of new members, some analysts called it the “big bang” of EU expansion. Europe had never achieved anything close to this level of political integration. The new EU members included Cyprus, Malta, Poland, Latvia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Slovenia, Lithuania, Slovakia and Hungary. Along with this enlargement came concerns relevant to this research, such as “government responses to perceived cultural threats and anti-immigration sentiments in public opinion” (Sedelmeier, 2014, p. 2) among member states. These concerns over popular backlash to the EU’s rapid development would bear out in later conflicts between EU member states, particularly between Eastern European states such as Hungary and EU leadership in Brussels.

The process of the integration of Europe into a supranational political body (in the form of the EU) and the process of globalization are distinct phenomena. However, in Europe, the expansion of the EU is paramount to the process of globalization because former lent the mechanisms needed for the latter, as “the EU developed a policy of regulated globalism in part because the union had to put in place regulatory frameworks for the governance of European integration, meaning that these frameworks offered themselves as templates when interdependence gathered pace at the global level.” (Youngs & Ulgen, 2022) So, since its inception, the EU has been outward-facing in its orientation, which has put it at the forefront of globalization. Per the KOF Globalisation Index, the top three most globalized countries in the world – the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland — are located in Europe (although Switzerland is not a member of the EU). (Swiss Economic Institute, 2021)

Despite its dubious record of achieving stated aims, globalization is normatively attractive to adherents of liberal ideology such as the European Liberal Forum who prize internationally-oriented policies to reduce inequality and promote human welfare: “Over the course of the development of the EU, we have stressed how important cooperation and coordination among its Member States is to defending and enhancing the freedom and prosperity of their citizens.” (European Liberal Forum, 2014, p.3) The European Union has been described by some analysts as “a bulwark of the liberal international order” (de Paiva Pires, 2022) because of its emphasis on transnational governance.

Accordingly, “liberal political parties and organisations throughout Europe traditionally have a strong pro-European profile,” (European Liberal Forum, 2014, p.3) meaning they support greater political integration of the continent. Attenuating the destabilizing effects of inequality, according to liberal doctrine, produces stability and promotes prosperity and peace; Rodrik cites the importance of “social policies to address inequality and exclusion,” concluding that nations that implement these policies will fare enjoy greater economic and social benefits than those that do not (Rodrik, 2013, p. 447). Globalization is one such development “propagated by the international development agencies [that] focuses on the shift in thinking which occurred in the 1980s… known as the ‘Washington Consensus.'” (Gore, 2001, p. 318), which encouraged national governments to open up trade with the outside world and to liberalize capital accounts to enable free movement of capital as a means to achieving mutual prosperity among states.

Globalization has been a dominant and major international phenomenon following the political and economic devastation wreaked by World War II: “Since the Second World War, globalization has been underpinned by a liberal international order, a rules-based system structured around the principles of economic interdependence, democracy, human rights and multilateralism.” (Money, 1997) Neoliberalism, a branch of the liberal school of thought that gained popularity among Western political elites and policymakers in the late 20th century, “postulates that the reduction of state interventions in economic and social activities and the deregulation of labor and financial markets… have liberated the enormous potential of capitalism to create an unprecedented era of social well-being in the world’s population.” (Navarro, 2007) Coinciding with the rapid increase in globalization beginning in the 1980s, “one of the most marked changes in the sociopolitical landscape of European societies since the 1980s has been the rapid and widespread adoption of neoliberal policies across the continent.” (Mijs, et al., 2016, p. 1)

Although globalization is largely favored among elite policymakers and academics, especially in the West where liberalism is arguably ideologically hegemonic, it does have its detractors. According to one critique, for instance, “neoliberal globalization is comprised of four processes: accumulation by dispossession; de-regulation; privatization; and an upward re-distribution of wealth” that, taken together, create numerous sociopolitical dilemmas such as “rising global inequality” and “threats to identity,” (Gandesha, 2018) both of which will be explored here.

Because “European governments and the EU collectively played important roles in shaping globalization… over many decades, the EU was a powerful force in extending international trade,” (Youngs & Ulgen, 2022) Europe is regarded as one of the foremost supranational organizations driving the phenomenon forward. As such, its member states have been among the first and most heavily affected by some of the (largely unintended) consequences of globalization, such as its effects on inequality, its diminishing impacts on national sovereignty, and strain on certain domestic industries within member states, explored now.

Globalization vs inequality

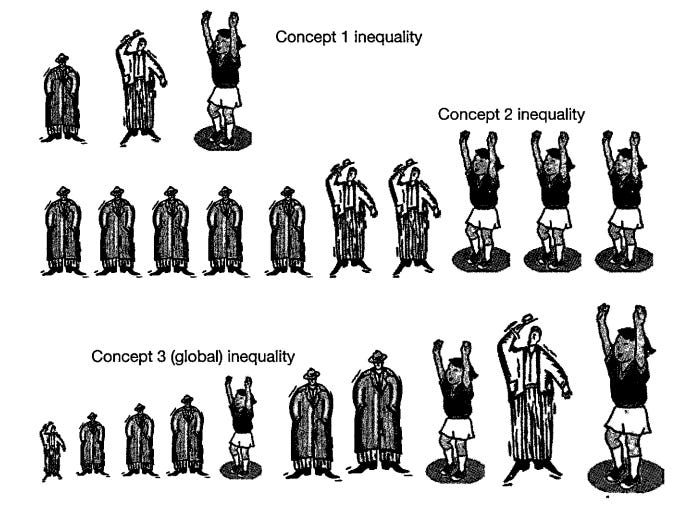

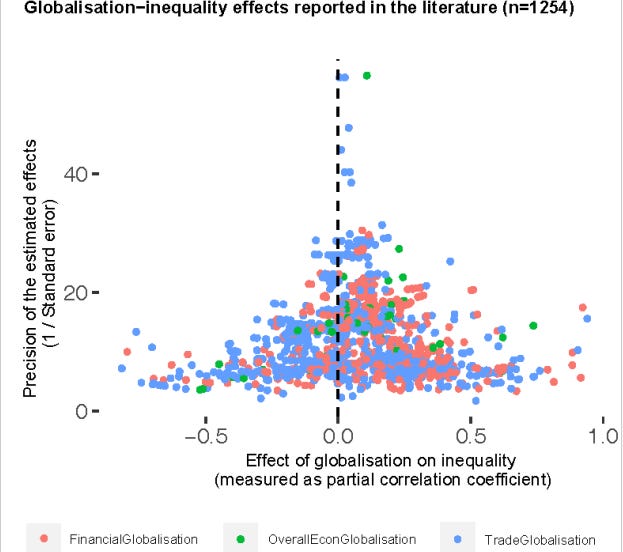

The evidence of globalization’s neutralizing effects on poverty and wealth inequality is mixed and nuanced. It does, importantly, bear out globalization’s neutralizing effect on inequality in certain contexts but, upon further examination, this claim is misleading when applied generally. Branko Milanovic, in “Global Income Inequality in Numbers,” parsed global inequality by applying three separate formulas to analyze global inequality numbers – “Inequality 1,” “Inequality 2,” and “Inequality 3.” Inequality 1 measures inequality between states without regard to population. Inequality 2 factors population into the otherwise same equation as Inequality 1, weighing countries with higher populations more heavily. Inequality 3, finally, the most data-intensive, uses an individual-level approach to measuring inequality without breaking the data up by nationality. (Milanovic, 2013, p. 417)

Milanovic then charts measurements of the three concepts, respectively, across time to determine whether, and to what extent, if any, inequality has declined using each metric. He found that, while Concepts 1 and 2 have declined precipitously since 1990, the same cannot be said of Inequality 3, which has remained more or less unchanged in the past several decades.

To summarize the relevancy of Milanovic’s findings to this research, globalization has produced reductions in inequality between nations, as promised. But an individual-level analysis of wealth inequality, as indicated in Concept 3 in the above illustration, shows that inequality between the ultra-wealthy and the ultra-poor regardless of nationality has remained elevated since the advent of globalization in the 1980s.

Analysts often point to reductions in Inequality 1 and 2, on the heels of massive economic development in developing countries like India and China, as globalization success stories – and arguably deservedly so. Indeed, developing low and middle-income countries have, on average, economically benefitted significantly from globalization by many estimates, as “a government committed to economic diversification and capable of energizing its private sector can spur growth rates that would have been unthinkable in a world untouched by globalization.” (Rodrik, 2011)

As a result of the inflow of foreign investment and reduced trade barriers facilitated by globalization, worldwide “between 1990 and 2015… some 900 million people entered the $10-per-day middle class and another one billion people escaped dire poverty of just $2 a day or less.” (Birdsall, 2017, p. 130) Taking these numbers alone, it would appear that globalization is a boon for reduced inequality.

However, those bullish assessments of globalization’s economic benefits frequently neglect to mention that globalization has produced no such decrease in Inequality 3 – the kind that, again, measures individual inequality levels across the board, in both developed and developing countries. Since the 1990s, “the larger (and still far richer) middle class in the West has declined in size, and the prevailing mood among many of its members is one of anxiety and pessimism about their future prospects including those of their children,” (Birdsall, 2017, p. 131) indicating negligible benefits for the middle and working classes of developed countries, many of which are located in Europe.

This reality comes with electoral consequences for the states that champion pro-globalization, pro-liberalization economic policies. Although they might not necessarily begrudge the gains of the middle and working classes in other states, humans are not by nature altruistic. If the economic gains enjoyed by developing countries conferred by globalization are perceived to come at the expense of the electorates in developed countries such as Europe, far be it for the average European member of the middle or working class, whose life has not materially improved due to globalization based on Milanovic’s Inequality 3 model, to celebrate the relative gains of the working classes in India or China with the same level of enthusiasm.

Austerity – the practice of attempting to reduce national debts through tax hikes or spending cuts or a combination thereof, often under coercion from international creditors –

“lead[s] to sharp reductions in welfare spending, cancellation of school building programs, severe reductions in local government funding, increased VAT and tax levels, the abolition of governing bodies and reduced spending on public services.” (McMahon, 2017)

Austerity is increasingly relevant as a political issue, as by some estimates, “by 2023, 85% of the world’s population will live in the grip of austerity measures.” (Abed, 2022)

There are many potential domestic causes of austerity, including the collapse of internal tax revenues and national debt accumulation. (Maldowitz, 2014). However, globalization arguably plays a role in spurring austerity policy in developed countries, as evidenced by the international global financial crisis of 2007-2008 that “changed the post-war observation that sovereign debt burdens were largely the concern of emerging market countries. As government balances deteriorated, public debt-to-GDP ratios in advanced countries surpassed those of emerging markets, rising to levels not seen since World War II.” (Bosner-Neal, 2015, p. 545)

As Martell notes, “austerity has a lot to do with globalization… in terms of the global nature of the financial crisis.” (Martell, 2014, p. 12) In other words, national economies that are interconnected through globalization to other economies suffer the negative consequences of foreign economic downturns, in turn driving a need for political solutions that are often presented as austerity measures.

Globalization opened up new economic vulnerabilities to instability in the global banking system that previously did not exist, as “even countries that have benefited from globalization in the past… are vulnerable… globalization increases vulnerability through a variety of channels, including trade and financial liberalization.” (United Nations, 1999, p.1)

As a result of the 2007-2008 economic crash and its aftermath, austerity policies were instituted across Europe: “either of their own volition or at the behest of the international financial institutions, [national governments in Europe] adopted stringent austerity policies in response to the financial crisis.” (McKee, et al., 2012)

Austerity is recognized to hit working-classes and middle classes, which depend more heavily on the public welfare system, the hardest:

“austerity measures aimed at curtailing public debt have impacted tremendously on the living standards of the middle class. Even in some of Europe’s most stable economies, the middle class is struggling.” (Ulbrich, 2015)

Specifically in the context of the EU, “austerity policies have expanded inequalities and undermined rights… Disparities in income have widened, the poorest getting poorer as welfare support declines and incomes are cut, while the rich continue accumulating income and wealth.” (Martell, 2014, p. 15) Some analysts have issued even starker warnings on the detrimental impacts of austerity on inequality and poverty in Europe: “austerity measures are weakening the mechanisms that combat inequality. Income is being increasingly unequally distributed; rising for the richest and falling for the poorest.” (OxFam, 2013a, p.11)

Does globalization undermine national sovereignty?

People move more freely across national borders in a globalized state as well. In addition to trade liberalization and capital flows, globalization is characterized “by transnational movements of people in search of better lives and employment opportunities elsewhere.” (Cholewinski, 2005) Globalization has resulted in the increased freedom of movement of workers and tourists alike without regard for national borders: “The unprecedented volume and speed of human mobility are perhaps the most conspicuous manifestations of the present era of globalization…. the phenomenon’s main driving force is the global expansion of capitalism and the free-market system.” (Knobler, et al., 2006)

Increased freedom of movement is most evident in the case of the European Union, given the previously outlined, unprecedented transnational Schengen Area, joining together dozens of European states in a free movement zone with no internal migration controls. One of the “fundamental principles” of EU membership is the “free movement of workers… enshrined in Article 45 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and developed by EU secondary legislation and the Case law of the Court of Justice.” (European Commission, n.d.) Under these provisions, EU citizens (which include every citizen of every EU member state) “are entitled to look for a job in another EU country, work there without needing a work permit, stay there even after employment has finished, [and] enjoy equal treatment with nationals in access to employment, working conditions and all other social and tax advantages.” (European Commission, n.d.) This has important implications for domestic workers that will be explored further in a later section of this research.

Global capital, along with post-nuclear geopolitics, environmental danger, and identity politics, is considered by some analysts to be one of the four principle threats to the state in the modern era. (Mann, 1997, p. 472) Globalization, which “has forced states into increasing competition for hi-tech industrial advantage” (Manchester Business School, 2017) in the global marketplace, weakens the position of the state. It exerts less and less influence over economic activities within its borders: “If globalization, in part, involves the emergence of supra national [sic] authorities because of new transnational problems resulting from growing trade, foreign investment, financial market interdependence and rapid technological change within a globalizing economy, then it seems only too natural that this process too will lead to supra national authorities eventually acquiring more jurisdictional power and nation states declining.” (Whalley, 1999, p. 1) This incursion of supranational authorities into areas of economic activity traditionally exclusively under the jurisdiction of states is a generally-held consensus, although some scholars like Mann point to the state’s continued social existence and the disparate impacts of globalization on various states as evidence that they maintain their primacy in the present era. (Mann, 1997, p. 472)

Protectionism vs globalization

Globalization stands in stark contrast to trade protectionism, which “protects domestic industries from unfair foreign competition… [using] tariffs, subsidies, quotas, and currency manipulation.” (Amadeo, 2022) Globalization is at odds with protectionist policies, as the latter are overwhelmingly favored by populist leaders who have “often used nationalism to justify protectionist policies that favor select domestic lobbies and have been at the forefront of trends in deglobalization.” (Ciravegna & Michailova, 2022, p. 175) There is debate regarding the extent of deglobalization and whether it exists as a phenomenon, but what is indisputable, as documented in an upcoming section on “far-right” politics and parties, globalization has increasingly become a highly relevant political issue in national politics in Europe.

Protectionism is anathema to liberalism. As Amadi notes, “a major contradiction of liberalism is ‘protectionism,’ which is the process of imposing trade restrictions such as tariffs to boost domestic industry.” (Amadi, 2020, p. 6) Under liberal theory, economic decisions are best left to the individual consumer outside of state influence to sort through cost, quality, etc. and make the most rational, self-interested decision possible. No preference is granted to domestically produced goods vs imported ones. The state does not intervene to favor domestic production over the import of foreign goods. Each nation unit produces the goods (and, increasingly in developed countries, the services) it is best suited to produce, based on its geographic location and human and natural resources. Adam Smith, one of the original purveyors of free trade, argued that if imported goods are cheaper than domestically produced ones, then importation makes good economic sense. (Smith, 1776, p.36) The EU has led the way in combating protectionism within its borders when it “implemented a program to create the world’s largest single market and embarked on creating a common currency.” (Hanson, 1998, p. 55)

Effects of globalization on domestic politics and populations in France and Hungary

Explored here are three potential effects of globalization on France and Hungary:

Transnational immigration

Defined as “a process of movement and settlement across international borders in which individuals maintain or build multiple networks of connection to their country of origin while at the same time settling in a new country,” (Upegui-Hernandez, 2014, p. 2) transnational immigration is a consequence of globalization in highly globalized states. Academics disagree on its merits, but the fact is not disputed that globalization has been a boon for transnational immigration. Analysts note that “increased migration is one of the most visible and significant aspects of globalization.” (Tacoli & Okali, 2001, p.1)

Talani cites increasing interconnectivity between states, “resulting in more people than ever before choosing to live and work in other countries,” (Talani, 2022) as a result of globalization. Economic mandates factor heavily into the increase in transnational migration in globalized states. Demand for unskilled labor by developed economies, such as many of those in the European Union, drives transnational migration: “The global reorganisation of labour markets has an important impact on migration. In the North, demand is high for semiskilled and unskilled workers, such as cleaners and housemaids, and for seasonal agricultural workers.” (Tacoli & Okali, 2001, p. 2)

Central to the question of transnational immigration from a political perspective is whether any entity can truly control the phenomenon. And, if so, who or what is in control: “It is quite possible… that the forces unleashed by globalisation escape governance as they are structural necessities… and therefore the urge to migrate cannot be stopped by political entities,” (Talani, 2022) Essentially, it appears as if no one is steering the ship – no one or no thing is truly in control, including state authorities in charge of policing international borders. Perceived lack of control resulting from an influx of foreign migrants may aid “far-right” political parties because “sensing a lack of control tends to have a reinforcing effect on voters with nativist attitudes in support of [radical right populist parties].” (Heinisch & Jansesberger, 2022, p. 1) The connection between transnational immigration and the proliferation of populist, “far-right” parties and ideologies in Europe is explored in further detail in an upcoming section.

Perceived loss of national/cultural/ethnic identity

How does globalization impact national identity, if at all, from the perspective of the domestic voting public? In popular perception – if not also in reality — national identity is at odds with the phenomenon of globalization in fundamental ways: “Nationalists and religious traditionalists fear that globalization will undermine cultural and other norms.” (Friedan, et al. 2017, p. 16) Often, perhaps out of social convention and discretion, the exact theoretical mechanism through which the culture will be “undermined” is not explicitly stated, but it is understood to be caused by an influx of immigrants who will introduce their own cultures and norms which will then spread throughout the population at large. According to the “clash of civilizations” theory, pioneered by Samuel Huntington, states are “differentiated from each other by history, language, culture, tradition and, most important, religion.” (Huntington, 1996, p. 282) The differences serve to stoke distrust, resentment, and hostility between cultures. He warns that “the interactions among peoples of different civilizations enhance the civilization-consciousness of people that, in turn, invigorates differences and animosities stretching or thought to stretch back deep into history.” (Huntington, 1996, p. 282) Peoples tend to be protective of their own cultural heritages, which necessarily excludes others. Culturally-based conflicts spill over into the political sphere.

In-group/out-group identity forming is a foundational element of sociology, predicated on the distinction between members of a social group and the amorphous, excluded “other.” Per Tajfel, et al. (1979), social groups confer identity and, with it, a sense of pride. The world is then dichotomized between “us” and “them.” Through this process, the differences between the in-group and out-group are amplified along with similarities among members of the in-group. Nationalism is, by definition, exclusive, since “the most messianic nationalists do not dream of a day when all the members of the human race will join their nation in the way that it was possible, in certain epochs, for, say, Christians to dream of a wholly Christian planet.” (Anderson, 1993, p. 7) That is to say, nationalist ideology – specifically, “exclusive nationalism” as defined in the following paragraph — does not allow for the same kind of assimilation into the native culture that liberal states have traditionally advocated for because it rejects new members from the out-group out of hand.

In particular, the variety of nationalism driven by an aversion to the influences of the outside world and peoples and manifest in “far-right” politics is called “exclusive nationalism” because it emphasizes in-group/out-group dynamics: “many newly ascendant nationalisms legitimate internal racial, religious, and ethnic hierarchies among citizens of their own countries…. it is not nationalism per se, but exclusionary nationalisms (also called ethnic or essentialist nationalisms) that are problematic for outcomes such as democracy.” (Mylonas & Tudor, 2021, p. 111) Because there is no interest among certain factions of the population in mingling with the outside world – and indeed, such mingling is viewed not just as undesirable but as an inherent threat — there is nothing to be gained socio-politically from globalization in the same theoretical way that it might benefit the economy, and everything to be lost in that regard.

Uneven distribution of economic benefits across social strata

The previous two effects of globalization touch on the issue of the threat to national identity. The final effect of globalization explored here is economic in nature. Specifically, globalization may exacerbate class divides by conferring disproportionate economic growth to the higher echelons of the socioeconomic ladder. As alluded to previously, globalization has disparate impacts across economic strata, tending to benefit upper-income brackets more so than the working and middle classes: “neo-liberal development aids the rich more than the poor, or at their expense… reproducing a linear rather than a relational conception of development’s co-ordinates of poverty and wealth.” (McMichael, 2012, p. 78) Various fleshed-out theories, such as trade theory, predict this dichotomy: “Trade theory tells us that the group… most likely to lose from globalization, or at best to gain less than everyone else, is labor.” (Deardoff & Stern, 2001, p. 6)

The lower economic classes, particularly low-skilled workers and the less-educated who benefit least from globalization, and the political parties that represent them, have taken note: “With growing economic inequality, low-skilled workers in the developed countries are turning increasingly against trade and immigration-feeding nationalist parties across Europe and North America.” (Friedan, et al. 2017, p. 16) Deardoff and Stern note “Growing opposition to globalization by organized labor… Because labor has lower income than those with income from other sources, and because trade lowers the relative wage, it tends to make the poor relatively poorer.” (Deardoff & Stern, 2001, p. 6) The working class – again, concentrated particularly in manufacturing and other unskilled labor-intensive economic activities — struggle with trade liberalization via globalization: “illiterate and other poorly trained workers in developing countries, designated as ‘NO-EDs/’ do not have even the minimal skills to benefit from unskilled labor-intensive exports. NO-EDs therefore may not have experienced the wage pull [from liberalization] that more educated but still unskilled compatriots might have enjoyed.” (Baker, 2005, p. 318)

Furthermore, globalization may not reduce inequality within states, despite popular perception to the contrary. Depending on the type of globalization, it may worsen inequality, as evidenced in Milanovic’s breakdown of three types of inequality explored in a previous section. To briefly rehash the results of his study, he found that, when the measure of inequality is conducted on an individual level independent of nationality, global inequality has remained the same since the 1980s. (Milanovic, 2013, p. 418)

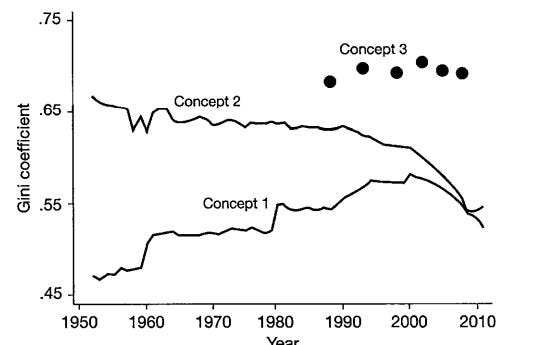

In Heimberger’s meta-analysis of the effect of globalization on inequality, he refined the variables used to distinguish between the effects of trade globalization versus the effects of financial globalization on inequality, and concluded that “globalisation has, on average, a small-to-medium-sized effect of increasing income inequality. Trade globalisation has influenced income inequality to a lesser extent than financial globalization.” (Heimberger, 2020) Europe has become increasingly highly financially globalized: “after 1987 most of the [European] countries liberated their capital account[s]… [and] progressed significantly into financial globalization.” (García, 2012)

(Heimberger, 2020)

Globalization also makes the local population more aware of economic realities outside of their borders, as well as how the global economy at the global and regional levels of analysis is impacted by globalization in comparison to globalization’s effects on domestic national economies, partly due to “the greater influence of other people’s (foreigners’) standard of living and way of life on one’s perceived income position and aspiration.” (Milanovic, 2013, p. 416) Domestic political awareness is also drawn to globalization’s potentially negative impact on domestic labor markets. (Dadush & Shaw, 2012) Interconnection and interdependency are a double-edged sword that is often overlooked by proponents of liberalism in order to emphasize its positive potential. The domestic electorate because increasingly aware, also, that “as the financial crisis of 2008 and the political instability that continue[d] to roil both developed and developing countries [made] clear, countries in the international economy are highly interdependent and closely integrated.” (Friedan, et al., 2017, p. 5) International economic malaise portends domestic political and economic malaise.

The economic goings-on in foreign countries impact everyone, potentially driving resentment or hostility towards foreign nationalities or ethnicities based on the damaging influences of foreign economic challenges as well as the increased competition faced in a globalized marketplace, particularly for blue-collar work: “Heightened import competition and increased offshoring… have affected the sectoral composition of employment and reduced the demand for low-skilled workers relative to medium- and high-skilled workers.” (Coe, 2010, p. 139) This trend, by its disparate impact on workers depending on skill level, will by its very nature drive inequality and potentially produce domestic political discontent within lower economic strata.

‘Far-right’ politics and parties

The previously described phenomena induced by globalization may have produced domestic political backlash from the voting populations affected by them. This backlash, in turn, may explain the largely unexpected rise in popular support for “far-right” political parties in Europe (with France and Hungary, the case studies here, serving as potential microcosms of European states across the continent as a whole).

For whatever benefits globalization might confer, the process of economic and social integration that is part and parcel of globalization necessarily requires concessions from nationalists who identify culturally and politically with the state. In popular usage, “far-right” politics are often used synonymously with “right-wing populism.” Far-right populism is defined as “a political ideology which combines right-wing politics and populist rhetoric and themes. The rhetoric often consists of anti-elitist sentiments, opposition to the perceived ‘establishment’, and speaking to the ‘common people’… populism of the right normally supports strong controls on immigration.” (European Center For Populism Studies, 2022) The interrelated ideologies of “nativism, authoritarianism and populism” are generally regarded as the three pillars of “far-right” ideology. (Remshardt, 2012)

There is a juxtaposition of terminologies at play that requires clarification. The term/label “liberalism” as it is used in the international realm should not be confused with domestic political ideologies of the same name in the West. At the domestic level, liberal (as in left-wing) ideology is, in fact, in the West, associated with protectionist policy positions, whereas “conservativism” (as in the right-wing) is traditionally more supportive of free trade (Friedan, et al., 2017, p. 8), arguably due to its business-friendly orientation. However, these left-right simple dichotomies in comparative politics are becoming more difficult to draw as ideologies bleed into each other and the international and national levels of analysis become more intertwined as globalization accelerates.

The “far-right” may also be referred to in social science literature as the “extremist right” (ER). Usually, although their ideological opponents use the labels, “far-right” parties do not label themselves “fascist” or “authoritarian” because of the stigma of these terms in post-WWII and post-Cold War Europe: “the spectacular growth in nationalist-populist parties in the nineties was made possible by an ideological renewal that had become necessary because of the discredit into which movements claiming to be in the tradition of fascism or authoritarian regimes… had fallen since 1945.” (Gjellerod, 2001)

In rhetoric and policy, right-wing populist parties are generally opposed to globalization. On the other hand, left-wing parties, though they criticize certain negative impacts of globalization, are more supportive of the phenomenon: “Whereas left-wingers have often been characterized as ‘new globals’ who seek to advance an alternative type of globalization, right-wingers emerge… as the true ‘no globals’, resisting any aspect of globalization.” (Della Porta & Caiani, 2012, p. 168) As previously alluded to, their principle objections to globalization is the detrimental impact on the native culture wrought by foreign influence and transnational immigration, although concern over economic impacts also features in their rhetoric.

Populism as a political ideology consists of several variants with important contrasts. The most prominent dichotomy is between right-wing and left-wing populism. Right-wing populism differs in fundamental ways from left-wing populism (sometimes described alternatively as “exclusionary” and “inclusionary” populism, respectively). Both forms of populism appeal, by definition, to the sensibilities of ordinary people – “the people” — outside of the prevailing power structure and champion their interests, at least rhetorically, against an elite governing class that is often considered corrupt or indifferent to the needs of the lower economic and social strata.

However, while left-wing populism conceptualizes “the people” in relation to prevailing institutions and social constructs – for example, to capital and the state — “right populism conflates ‘the people’ with an embattled nation confronting its external enemies: Islamic terrorism, refugees, the European Commission, the International Jewish conspiracy, and so on.” (Gandesha, 2018) In other words, right-wing populism has often been defined as “exclusionary” (of different ethnicities, religions, and nationalities, for instance) while left-wing populism is described as “inclusionary.” Left-wing populism is often internationalist in its orientation, sometimes going as far as decrying the concept of the state, while right-populism holds fidelity to the state above all as the homeland of “the people,” usually defined in ethnic/cultural/religious terms.

Research indicates that strong nationalist identity and ethnocentrism are important features of “far-right” ideology. (Falter & Schumann, 1988, p. 97) “Far-right,” or right-wing populist, politics defies the conventional wisdom, according to which the working classes tend to support left-wing parties, which are generally considered friendlier to worker and organized labor: “Rightist parties which appeal to nationalism and traditional social issues can invoke more authoritarian values among the working class and those with less education. The consequences may be low and even ‘negative class voting’ where the conservative parties gain strong support from segments that belong to the left in contexts where the economic left–right divide” (Knutsen, 2013) is considered most relevant. “Far-right” supporters, however, need not necessarily fit any pre-conceived stereotype; activists across the ideological spectrum in Europe at large “worry that footloose corporations may undermine attempts to protect the environment, labor, and human rights,” and have accordingly embraced anti-globalization, nationalist, and protectionist political parties. (Friedan, et al., 2017, p. 16)

Daniel Oesch (2008, p. 349) explains that “during the 1990s, the working class has become the core clientele of right-wing populist parties in Western Europe.” The tendency for the poor and working classes to vote for, and identify with, the right vexes many analysts who see their economic interests represented more on the left: “across the world, blue-collar voters ally themselves with the political right – even when it appears to be against their own interests.” (Haidt, 2012) There are likely many possible reasons that the poor and working classes are predominately attracted to far-right party membership, but one clear reason is the disproportionate impact of immigrant/refugee policy on groups lower in the socioeconomic hierarchy: “The language of xenophobic discrimination in this context is often the language of perceived scarcity and competition… all over the world, the socio-economic implications of urban refugee protection disproportionately fall on the urban poor and working classes.” (Achiume, 2018)

One common argument for the often unexpected success of “far-right” populist parties in Europe in recent years is that the general “far right” at the international level (perhaps via globalization) influences and drives domestic far-right movements within European states, such as those in Hungary and France. However, this appears not to be true because “right-wing extremist parties… are all (alleged) nationalistic movements, which would make them particularly country-specific and thus incomparable.” (Mudde, 2007, p. 226) Each nationalistic movement has its own objective of preserving the native culture, so its common cause with other nationalistic movements is limited.

Aside from a general shared European heritage, there is little that would bind far-right movements across national borders because their ideologies are so closely intertwined with local cultural and ethnic identities. Therefore, the thesis of this paper remains that there are localized phenomena — occurring at the domestic political level and induced by globalization — that explain the rapid growth of the “far-right” in Europe. Despite many illiberal facets of their ideology and governing philosophies, which would seem to eschew electoral politics, “the extremist parties and movements in Europe no longer operate outside the democratic system, which they have so often decried, but within it.” (Gjellerod, 2001)

The perception of a rigged or unfair (or both) economic system in the new century may have worsened popular anger along economic lines, and many point the finger at globalization for the relative decline of the middle-class standard of living due to austerity. Among the “multiple economic, social, cultural and political causes for the current rise in the radical right in various European countries,” Cesáreo Rodríguez-Aguilera concludes that the “economic crisis triggered in 2008 and the ensuing single-minded pursuit by EU and national authorities of neoliberal deficit-control and austerity measures are one key factor.” (Rodríguez-Aguilera, 2014)

Some analysts argue that austerity is an inevitable consequence of continued globalization: “Austerity is not just a consequence of the global financial crisis but is here to stay as states grapple with the wider impacts of globalisation and the difficulty of increasing state spending” arguing that “modern forces undermine the ability of nation states to increase both welfare and infrastructure spending.” (Alliance Manchester Business School, 2017) In the fallout of the 2007/08 crash, the media has documented “efforts of extremist parties to win support by plugging into popular discontent over the financial crisis, against the backdrop of a wider social unease and anti-immigrant sentiment.” (Smith-Spark, 2012)

Methodology

This research will utilize a combination of qualitative and quantitative analysis. Globalization is a cultural and political as well as an economic phenomenon. Each of these varieties of globalization has distinct impacts on the populations that experience them that might inform voting behavior and voters’ attitudes. France and Hungary — from Western Europe and Eastern Europe, respectively, and a founding member and a relatively new member of the European Union since 2004, respectively – will serve as the dual case studies examined in this research.

The three sociopolitical phenomena associated with globalization examined in this study, in the context of France and Hungary, will be: transnational immigration rates, the perceived loss of national/cultural/ethnic identity among the populations, and uneven distribution of economic benefits across social strata.

Transnational immigration rates into Hungary and France are quantifiable using EU aggregate data and data compiled by national governments at the state level. Perceived loss of national/cultural/ethnic identity is quantifiable using public polling data. Uneven distribution of economic benefits across social strata is likewise quantifiable using private and public-sector reports.

Having established and measured the metrics to indicate what sociopolitical changes globalization has caused at the state level, the research will then measure globalization’s impact on voting behavior. This study will analyze voting behavior at the national level in two European states, France and Hungary, from 1990-2020, when globalization within the EU accelerated.

The research will use the share of the total vote going to “far-right” nationalist parties in France and Hungary – the National Rally (RN) (formerly known as the National Front; the reasons for the name change will be explored in the section on “far-right” politics in France) and Fidesz-KDNP, respectively — which tend to adopt hardline rhetorical and policy stances against globalization, as the bellwethers of support for the “far-right.” In addition, this research will examine public polling data that can detail voter motivations that might otherwise be unclear based on raw vote tallies alone.

Because voters may prefer “far-right” parties over alternative candidates for any number of reasons, this research will also include exit polling in addition to electoral outcomes in national elections, in which voters express their motivations for voting the way they did. The results from France and Hungary will then be compared to identify common trends shared by the two European Union member states.

Evidence

In this section, the research will seek to answer several relevant questions: How did the three identified consequences of globalization – increased transnational immigration, perceived loss of national identity, and uneven distribution of economic benefits across social strata – specifically manifest in Hungary and France, respectively? Did “far-right” parties achieve greater electoral success between 1990-2020 than before? If so, what issues did these “far-right” parties campaign on as centerpieces of their platforms, and what motivations can be discerned on the part of voters who supported them based on polling data?

Hungary

In domestic politics, right-wing populist European parties are “known for their opposition to immigration, especially from the Islamic world, and for Euroscepticism[emphasis in original text].” (European Center For Populism Studies, 2022). In Hungary, “far-right” parties position themselves rhetorically against EU integration and globalization more broadly, framing them as threats to national sovereignty and national identity.

Hungary’s main “far-right” party, Fidesz-KDNP, headed by Viktor Orban, won power in 2010, (Gawron-Tabor, 2015, p. 290) following the 2007/08 global financial crash. It has held power since, winning parliamentary supermajorities in four separate elections from 2010 to 2022. There is good evidence that distrust in neoliberal, multinational financial institutions drove its success, as the Fidesz-KDNP campaigned on specific and relevant policy changes: “Prime Minister Orbán put forth his explicit aim to increase domestic ownership in banking to over 50% and legitimized the ensuing re-nationalization of the financial sector with resentment over neoliberal banking practices.” (Sebok & Simons, 2022, p. 1625)

Eastern/Central Europe was once ripe for liberalization and democratization in the model of the West following the demise of the Soviet Union in 1991. Unfortunately for proponents of liberalism, Cianetti et al. recommend that “this optimistic picture of democratisation in East Central Europe needs revising… the region appears to be mired in a range of negative phenomena subsumed under the label ‘democratic backsliding’ which impact on democracy as a regime threatening… an authoritarian reversal.” (Cianetti et al., 2018, p. 244) In other words, Hungry has experienced a popular rejection of liberalism and pluralism. Krekó concurs: “Since 2010, Hungary has gradually become a competitive authoritarian state or ‘hybrid regime,’ where democratic institutions exist in theory, but the rule of law and civil liberties are severely limited in practice.” (Krekó, 2022) What follows is an explanation of the electoral factors that may have driven that “democratic backsliding” in favor of more authoritarian, populist ideologies and how they may have increased the political viability of the “far-right.”

Transnational immigration to Hungary and national identity

For the past hundred years, since the end of World War I and the collapse of the Austria-Hungary Empire, Hungary has been “one of the most ethnically homogenous states” (Freifeld, 2001) in Europe. The vast majority of the Hungarian population is ethnically Hungarian, and in this way the national identity is closely intertwined with the ethnic one.

But with the ascension of Hungary into the EU in 2004, Hungary effectively opened its doors to immigration from within the EU, threatening to dilute the long-standing ethnic hegemony of Hungarians within Hungary. “Far-right” political campaigners in Hungary have seized on the ethnicity issue to declare that in the post-EU integration era Hungary “had allowed its ethnic identity to be diluted, washed too thin by the pull to the West, by urbanization, and by the heavy influence of Hungarian Jews in the culture and prosperity of the country.” (Freifeld, 2001) This, again, highlights the previously established incorporation of anti-Semitic rhetoric into “far-right” campaigning.

It is arguably true that some, if not all, of the popular support for “far-right” parties in Hungary (and, as explored in an upcoming section, France) would have materialized regardless of any marketing/electioneering efforts on the part of the parties. But we know that these types of parties historically intentionally capitalize on the growing resentment of native populations against immigration as a concept and immigrants as people: “Xenophobic discrimination cannot [original emphasis in text] be reduced to socio-economic determinants. Politically motivated scapegoating of forced migrants and even criminal opportunism, for example, may play an important role in influencing when host communities mobilize to exclude or harm refugees.” (Achiume, 2018)

With the role of political parties in fueling xenophobia in mind, Hungary’s Constitution, called the “Fundamental Law of Hungary,” passed under the ruling Fidesz-KDNP Party in 2011, explicitly outlines the ethnic and religious contours of the state: “We are proud that our king Saint Stephen built the Hungarian State on solid ground and made our country a part of Christian Europe one thousand years ago.” (Constitute Project, 2011, p. 4).

The document also gives a nod to “safeguarding” Hungarian culture: “We commit to promoting and safeguarding our heritage, our unique language, Hungarian culture, the languages and cultures of nationalities living in Hungary.” (Constitute Project, 2011, p. 4) With the usually subdued and technical official government as a contrast, one will note the comparatively brazen nature of the ethnonationalism expressed; even under the leadership of like-minded social conservatives in other Western countries, it’s rare to see commitments to “safeguarding” the culture so explicitly rendered in an ostensibly liberal state.

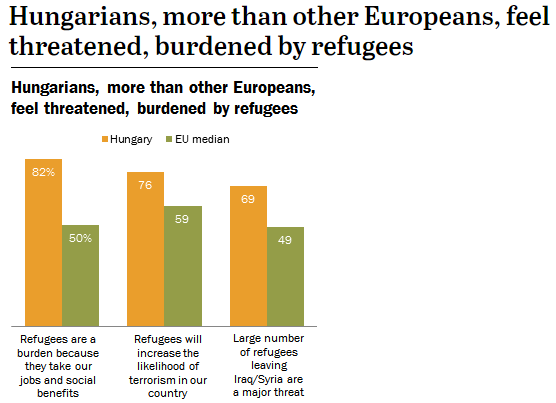

Asked in a 2017 poll “What do you think is the most important aspect of the EU that does not function well?”, Hungarian respondents overwhelmingly cited immigration control (20%) over any other concern. The next-biggest concerns, at 5% respectively, were “independence of countries” and “protection of the EU borders,” which also speak to concerns over transnational immigration. (Ipsos Hungary ZRT, 2017, p. 28)

In its Constitution, the Fidesz-KDNP Party, in no uncertain terms, rejects pluralism and secularism — both essential features of liberalism, especially in the context of the EU. As critics put it, the “new constitution… [passed under Fidesz-KDNP rule]… referred to… the subject of the constitution not only as the community of ethnic Hungarians, but also as a Christian community, narrowing even the range of people who can recognize themselves as belonging to it.” (Halmai, 2018)

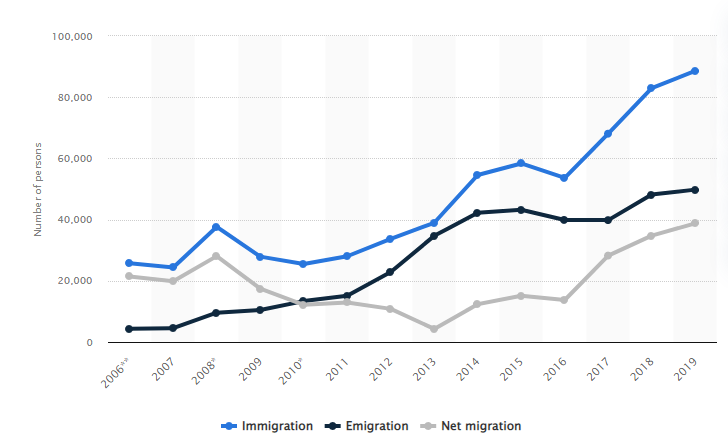

Owing to its geographic location in Eastern Europe, the period of 2015-2019 was particularly unprecedented for Hungary as millions of immigrants coming from the Middle East and North Africa attempted to make the journey to Germany and other further West European states – first via Greece to Macedonia to Hungary — due to their migrant-friendly policies and state support. (Ayoub, 2019, p. 4) In Hungary, “net migration ranged from 4,277 persons in 2013 to 38,786 persons in 2019.” (Statista, 2022) as illegal immigration became more widespread: “almost 12 thousand third country nationals were found to be illegally present in Hungary. This represented an increase of almost 100 percent compared to 2014.” (Statista, 2022)

(Statista, 2022)

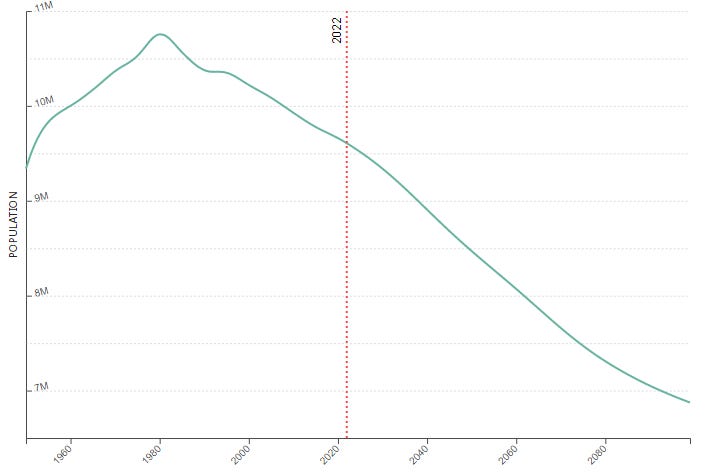

The demographic effect of an influx of transnational migrants into Hungary is exacerbated by the extremely low birth rate among the native population. In 2021, while the raw total of immigrants rises, Hungary’s overall population growth rate dropped into negative figures at -0.29%. That year saw 12.88 deaths per 1,000 Hungarians and just 8.72 births per 1,000 Hungarians. (Migration Policy Institute, 2022). The figure below depicts the downward overall population trend in Hungary.

Based on polling, the Hungarian population is overwhelmingly opposed to these demographic trends: “When it comes to Hungarians’ opinion on the topic, as of March 2020, over two-thirds of the population found illegal immigration a concerning issue.” (Statista, 2022) Expression of xenophobic attitudes expressed openly has increased along with the increase in transnational immigration and the rise of Fidez-KDNP in Hungary.

According to one analysis, “In 1992, 15 percent of Hungarians expressed xenophobic attitudes but the number increased to 39 percent by 2014 and reached a peak of 67 percent in October 2018.” (Krekó, 2022) This represents a more than four-fold increase in xenophobic attitudes in less than thirty years.

In an analysis alongside other EU member states, “Hungary… ranks extremely high compared with other European nations when it comes to exclusionary views on national identity.” (Manevich, 2016) A large majority hold negative views of Muslims and the more historic ethnic minority in Hungary, the Roma. Shockingly, one-third of Hungarians also express anti-Semitic views. (Manevich, 2016)

Xenophobic rhetoric within Hungary accelerated greatly around 2015, which coincides with “an unprecedented number of asylum-seekers” passing through Hungary,” (Krekó, 2022) mostly on their way to other EU member states perceived to be more welcoming of foreigners such as Germany. The Fidesz-controlled Hungarian government “was among the first countries in the European Union to capitalise upon the refugee crisis by politicising the question of immigration, therefore, several anti-immigration campaigns were initiated in Hungary during 2015 and 2016.” (Marton, 2017, p. 2)

Halmai (2018) notes that “The refugee crisis of 2015 has demonstrated the intolerance of the Hungarian governmental majority, which styled itself as the defender of Europe’s ‘Christian civilization’ against an Islamic invasion.” In 2015, amid criticism from the European Union and the broader international community to take in more refugees, Orban cited economic concerns in addition to the previously mentioned social ones over the question of immigration: “the stream of refugees would place an intolerable financial burden on European countries, adding that this would endanger the continent’s ‘Christian welfare states.'” (Reuters, 2015b)

In a 2015 speech, Fidesz-KDNP head and sitting prime minister Viktor Orban declared that “‘we would like to preserve Europe for Europeans…, ‘But there is something that we would not only like but we want: to preserve Hungary for Hungarians.'” (Reuters, 2015a) In his April 2022 victory speech, Orban targeted the EU, largely seen as the source of the influx of migrants and the resulting dilution of Hungarian culture: “Our win is so huge you can see it from the Moon, never mind from Brussels,” (Adler, 2022) referencing the EU headquarters in Belgium.

Moreover, in a 2022 speech Orban declared that “the great European population exchange [is] a suicidal attempt to replace the lack of European, Christian children with adults from other civilizations – migrants.” (Garamvolgyi & Borger, 2022) He also adeptly couches his rhetoric in the language of right-populism: “the millions with national feelings are on one side [apart from] the elite citizens of the world.” (Orbán, 2018)

Popular opinion notwithstanding, political pressure came to bear from within the EU, specifically from Germany, for other EU member states – especially those publicly opposed to accepting greater numbers of refugees such as Hungary — to foster more immigrants: “It isn’t just Germany, but all of Europe has a responsibility, and we have to remember that almost all refugees, and there are millions in the world, have often found refuge in a neighboring country,” said German Social Democrat head Scholz.” (Ridgwell, 2021) This may be seen as an imposition by a foreign power on the domestic politics of the state, a sentiment that might ironically be responsible for further entrenching the Hungarian electorate in opposition to immigration.

Inequality and austerity in Hungary

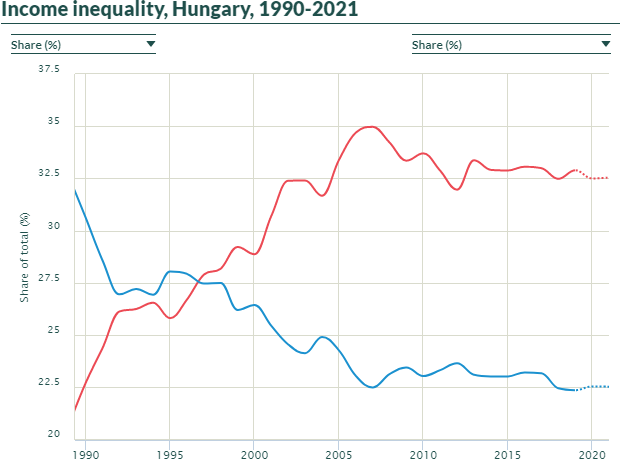

The chart below depicts the share of pre-tax national income going to the top 10% in red, juxtaposed to the share of pre-tax national income going to the bottom 50% in blue in Hungary from 1990-2021. In it, we see that Hungary, coming out of the Soviet Union, experienced a surge in top 10% elite wealth and a concomitant loss in the bottom half’s share of national wealth – the latter down from 30.6% in 1990 to 22.5% in 2020. Because of the collapse of state-planned communism in 1991 and the transition to a market economy, we may infer based on these figures – barring confounding factors — that neoliberal economic policies ostensibly did not reduce inequality in Hungary and, in fact, worsened it.

Viktor Orban and the Fidesz-KDNP have shrewdly avoided any austerity measures until very recently in 2022, when the party was forced to relinquish its hardline opposition to austerity due to skyrocketing inflation associated with the Russian invasion of Ukraine an energy shortages. (Varga, 2022) Prior to that, which may be considered an extenuating circumstance, austerity had come to Hungary in the aftermath of the 2007/08 financial crisis, during which time Hungary was forced into “more spending cuts following a balance of payments crisis [in 2008] that necessitated €20bn aid from the EU, IMF and World Bank,” (Traynor & Allen, 2010). Analysts compared Hungary to Greece, which was rocked by financial insolvency in the immediate past and forced to institute austerity packages. polling indicates that opposition to austerity measures was a major issue that originally won Fidesz-KDNP its 2/3 majority in parliament in 2010. (Benczes, 2014)

In Hungary, Viktor Orban and the Fidesz-KDNP, when it assumed power in 2010, following austerity, bucked International Monetary Fund orthodoxy and reversed course, refusing further austerity packages and instead levying a new bank tax to generative revenue for the public treasury. (Weisbrot, 2010) Even with concessions, the Fidesz-KDNP has continued to resist austerity measures, instead expanding state benefits to its constituents. In 2022, Orban “paid a ‘thirteenth-month’ pension to seniors, exempted people under 25 years of age from income tax, and buffered Hungarians from inflation by freezing fuel and food prices. In prior election years, such handouts have won many people over.” (Scheppele, 2022, p. 46)

Viktor Orban has consistently criticized the “left’s” penchant for austerity: “The left wing tightens belts, makes layoffs, raises taxes and lowers salaries in times of crisis, while the government does just the opposite: it supports job preservation, creates new workplaces, cuts taxes and provides wage support.” (Hungary Today, 2020) In 2018, “the [twenty] poorest villages and settlements in Hungary… voted overwhelmingly in favor of Fidesz-KDNP’s reelection.” (Vaski, 2022)

France

The predominate “far-right” party in France is the National Rally (RN), headed by Marine Le Pen. French nationalists – sometimes described as “nativists” – founded the National Rally in 1972, led by Marine Le Pen’s father, Jean-Marie Le Pen. Since its inception, stopping transnational immigration has been its primary focus: “Since its beginnings, the party has strongly supported French nationalism and controls on immigration, and it often has been accused of fostering xenophobia and anti-Semitism.” (Ray, n.d.) In 2018, the National Rally rebranded itself in an attempt to achieve more mass appeal. Its original name, National Front was abandoned due to its association with extreme xenohphobia, including anti-Semitism. (France 24, 2018)

Until the 1990s, when globalization began in earnest, the National Front (FN) remained relatively obscure, rarely winning more than 10% of the popular vote in national elections. But “by the 1990s the FN had established itself… In 1995 Le Pen captured more than 15 percent of the vote in the presidential contest, the FN won mayoral elections in Toulon, Orange, and Marignane, and a former FN member was elected mayor of Nice.” (Ray, n.d.)

The true turning point for the party came when it moderated its most extreme anti-Semitic views under the new leadership of Marine Le Pen: “She and a younger generation of allies initiated a process of ‘de-demonisation’, dropping some of the party’s most radical proposals… [older party members] were replaced with younger, savvier political operators.” (Phalen, 2022) Since cleaning house, so to speak, “the party has skilfully tapped into disenchantment with Macron and anger over the rising cost of living, globalisation and the perceived decline in many rural communities.” (Phalen, 2022) In France, low-income voters disproportionately vote for Nationally Rally candidates in national elections. (Thomas, 2022)

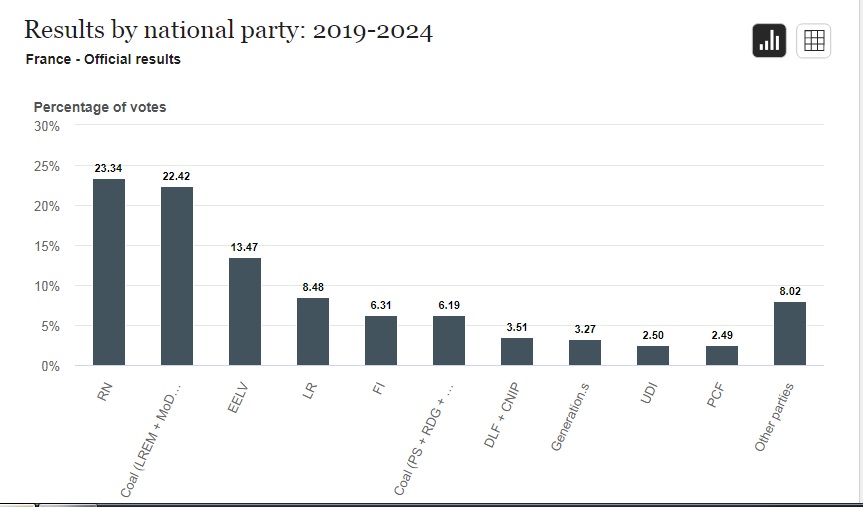

National Rally’s electoral rise from obscurity has been remarkable: “Between the National Assembly elections of 1973, which the RN was founded to contest in the name of a unified French nationalist right, and the… corresponding elections of 2012, the party increased its national vote share from 0.5 per cent (fewer than 125,000 votes) to 13.6 per cent (over 3.5 million votes).” (Shields, 2014, p. 41) By 2019, the National Rally had become the single best-performing party in France’s multi-party system.

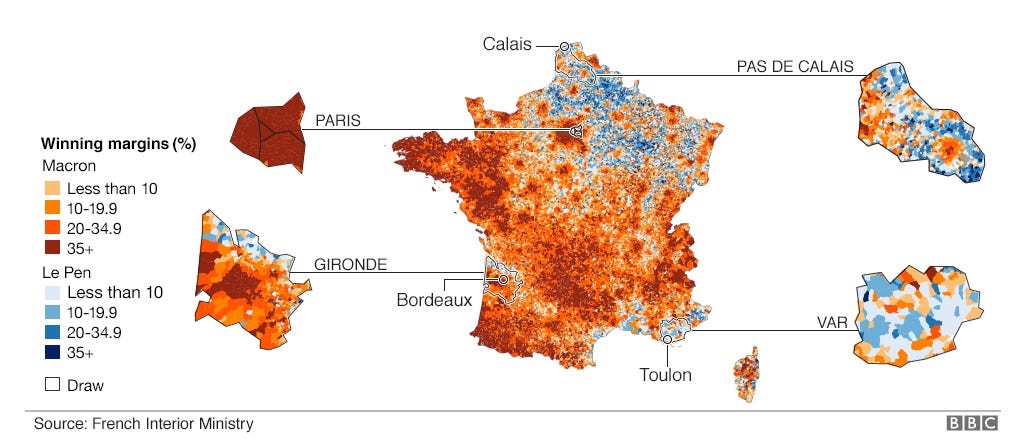

Demographic research indicates that a strong majority of right-wing voters in France live in rural areas, whereas the cities are more populated proportionally by left-wing voters. Newly arrived immigrants, perhaps due to perceived corresponding social benefits, tend to cluster within cities: “Cities have a much higher share of people born in another country (17% of the population of 15 and older in 2019 in the EU28) than other areas do (12% in towns and suburbs, and 6% in rural areas).” (De Dominicis, et al., 2020, p. 10) Furthermore, in the West broadly, “rural people are much more likely to desire decreased immigration when compared with urban people.” (Garcia, 2013, p. 96) The National Rally and other “far-right” parties consistently outperform rivals in rural, mostly white, mostly working-class regions. In 2017, for instance, Marine Le Pen dominated the French countryside whereas Macron fared far better in the large cities, demonstrating rural areas as her party’s unquestionable seat of power:

Interestingly, the major “Yellow Vest” protest movement against the French government’s proposed gas hike and social inequality generally originated due to “a feeling of neglect and exclusion in France’s exurbs and rural regions… where the French state and many institutions representative of French society have progressively disengaged over the past decade.” (Stephens, 2019) It is likely no coincidence that the regions of France that are most disaffected with social inequality and most hostile to transnational immigrants disproportionately vote for the National Rally.

Opposition to austerity and wealth inequality were central issues that drove the yellow vest protests: “The ‘yellow vest’ protests of hundreds of thousands that have taken place every week for the past six months have been driven by opposition to rising social inequality and poverty and dominated by demands for an end to austerity and a redistribution of wealth from the rich to the working class.” (Morrow, 2019)

In 2021, while running for the top elected national office against sitting PM Emmanuel Macron, popularly conceived to be friendly to the EU and globalization broadly, Le Pen laid bare the ideological divide that she hoped to exploit on her way to a victory: “[Emmanuel Macron] stands for unregulated globalisation, I defend the nation, which remains the best structure to defend our identity, security, freedom and prosperity.” (Reuters, 2021)

Transnational immigration to France and national identity

The differential fertility rates between native-born French women and foreign-born French women exacerbate the demographic trends in France. Along with an increasing share of the population represented by immigrants, France has experienced a steady decline in birth rates since 2015. (RFI, 2020) Furthermore, while the overall fertility rate in France was 1.9 per woman (near replacement level), the fertility rate of foreign-born women was 2.6 per woman in 2017 compared to 1.8 in 2017. 19% of all babies that year were born to foreign-born women. (Volant, et al., 2019)

Even as Le Pen is considered “far-right” – despite moderating since the days of her father’s National Rally — domestic political pressure came to bear from the right of Le Pen to impose harsher anti-immigrant policies. Eric Zemmour threw his hat into the ring in 2021 as a candidate for prime minister, declaring at his campaign launch that “you feel like you are no longer in the country you once knew … you are foreigners in your own country.” (Melander, 2021)

Zemmour, following a trend within France, explicitly referenced the Great Replacement Theory, sometimes known as “white genocide.” The premise of the theory is that shadowy powers-that-be are working in secret to flood white-majority countries with immigrants. The ultimate goal is attaining the dilution and annihilation of Western culture: “These theories focus on the premise that white people are at risk of being wiped out through migration, miscegenation or violence… these concepts have come to dominate the ideology of extreme-right groups.” (Davey & Ebner, 2019, p. 4). In recent years, sensing the electoral opportunities, more center-right parties in France such as Les Républicains (LR) have hardened their anti-immigrant rhetoric: “Eric Ciotti, a hardline conservative who unexpectedly won the first round of the [Les Républicains] primary last week, has promised to set up a ‘French Guantanamo’ and espoused the far-right theory that the French people are being ‘replaced’ by foreign — Arab, black, Muslim — immigrants.” (Momtaz, 2021)

In a 2020 poll of French voters, 53% and 52%, respectively, of respondents believed curbing illegal immigration and the perceived social and financial costs of that immigration were priority issues that the government should be working to resolve. (Institut français d’opinion publique, 2020, p. 70) According to the results of a 2021 survey of French voters, 71% of respondents reported believing that France had fostered enough immigrants, expressing their wish for it to stop. 64% of respondents were keen to reject all asylum seekers, citing their perceived involvement in terrorism. Nearly three-quarters (74%) expressed a belief that ethnic diversity causes social problems. (Le Labo de la Fraternité, 2021, p. 7)

One analysis, studying Danish municipal elections from 1981 to 2001, found that “local ethnic diversity lead to rightward shifts in election outcomes by shifting electoral support away from traditional ‘big government’ left-wing parties and towards anti-immigrant nationalist parties.” (Harmon, 2017, p. 1043) In another 2020 survey of French voters, 60% reported a belief that assimilating foreigners is not “pragmatic” due to intransigent cultural differences. (Institut français d’opinion publique, 2020, p. 44)

The phrase “France belongs to the French” is an often-repeated expression of the “far-right,” which has strong ethnic overtones. For instance, when, in 2013, ethnically Algerian Muslims in France went on a killing spree in response to Charlie Hebdo’s cartoon depicting the prophet Muhammed, “pork was left on the steps of a mosque with the inscription ‘France belongs to the French'” (Frydman, 2016, p. 85) – pork being a forbidden food product in the Islamic faith. In another instance of political rejection of multiculturalism, in the context of a push to include meals in public schools compatible with Islamic doctrine, Marine Le Pen said “We will accept no religious requirements in the school lunch menus. There is no reason for religion to enter into the public sphere.” (Janmohamed, 2014)

Inequality and austerity in France

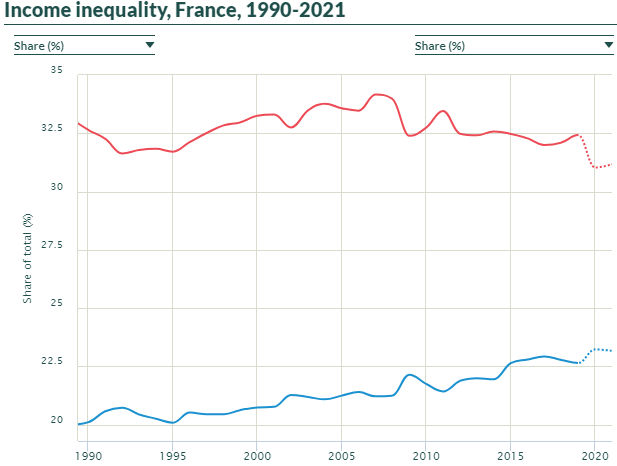

The chart below depicts the share of pre-tax national income going to the top 10% in red, juxtaposed to the share of pre-tax national income going to the bottom 50% in blue in France, from 1990 to 2020.

Here, we see that France’s bottom 50% marginally improved its share of national income from 20.1% in 1990 to 23.2% in 2020 while the top 10% essentially maintained its share. In this regard, the country is an outlier, as France was one of only five countries that OECD looked at from 1988-2008 that actually reduced inequality. (OECD, 2008, p. 1)

This has not stopped austerity from coming to France due to various international political crises, including the 2007/08 economic crash. In 2010, when France had a 99.1 percent debt-to-GDP ratio, it was forced to instate austerity programs under pressure from EU headquarters in Brussels. (Elleyatt & Amaro, 2018) The effects of globalization-induced austerity on the French population are felt disproportionately by the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. The economic fallout from the transnational 2007/08 financial crash and the resulting austerity measures instituted by the French government resulted in the increase of poverty rates in France from 7.8 million in 2007 to 8.6 million in 2013. Wages to the bottom twenty percent of earners in France decreased 1.3 percent while wages to the top twenty percent of wage earners increased by 0.9 percent. (OxFam, 2013b, p. 3)

French voters reject austerity in public polling. In one such survey, French voters supported increased government spending on public services: “Similarly, 59% agree that the EU’s fiscal rules should be changed to allow governments to increase spending on improving public services… Even more respondents (64%) are concerned about the potential impact of austerity should the EU try to force governments to cut borrowing to reduce their debts over the next five years.” (Syndicat European Trade Union, 2022, p. 1)

The National Rally has positioned itself consistently against austerity, including in 2019 when National Rally candidates in the European election “exploit[ed] the social crisis and anger produced by the austerity… policies of so-called ‘center-left’ or social-democratic governments over decades.” (Morrow, 2019) In that election, “Marine Le Pen’s far-right party came first in France’s European election and gained half a million more votes than last time… the far-right has steadily become a regular and unquestioned part of French political life despite political opponents condemning it as racist, Islamophobic, xenophobic and hate-mongering.” (Chrisafis, 2019) The National Rally has repeatedly framed its criticism of the French welfare state as unfairly benefitting immigrants at the expense of the native population, and, in keeping with exclusionary populist rhetoric, in her most recent presidential campaign promised a policy “prioritising French people’s access to welfare, social housing and jobs.” (Parker, 2022)

Similarities between the rise of the ‘far-right’ in Hungary and France

At the outset of this research, it was established that transnational immigration is a documented byproduct of globalization. (Tacoli & Okali, 2001, p.1) Globalization is also seen to drive perceived loss of national/cultural/ethnic identity among the native population (Friedan, et al. 2017, p. 16) – thereby driving the political development of “exclusionary “nationalism” (Mylonas and Tudor, 2021, p. 111) — and uneven economic benefits primarily advantaging the upper economic strata (McMichael, 2012, p. 78).

In turn, the effects of these general effects of globalization on political outcomes are examined in the two case studies here, using election results, public polling data, demographic characteristics of “far-right” voters, and “far-right” party rhetoric. There are numerous noteworthy parallels between Hungary and France that help answer the question of whether neoliberal, globalization-friendly policies within each respective space drove “far-right” political victories from 1990-2020.

Both political parties studied here, the National Rally in France and the Fidesz-KDNP in Hungary, rose to political prominence around the same time, in the context of broader political history, which coincided with a rise in transnational immigration since the early 1990s and the fallout of the 2007/08 financial crash, which included austerity measures. Fidesz won a supermajority in parliament in 2010, (Gawron-Tabor, 2015, p. 290) while the National Front won its largest-ever share of the vote (13.6%) in National Assembly elections in 2012, (Shields, 2014, p. 41). In each case, “far-right” parties have made opposition to foreign influence and international governance – transnational immigration, perceived loss of national/cultural/ethnic identity and uneven distribution of economic benefits being three effects of globalization — central to their platforms, particularly from 2010-2020.

Anti-globalization, and particularly anti-EU, rhetoric – globalization being often cited as a nefarious and corrosive influence on their respective native cultures — features prominently in both French and Hungarian “far-right” party rhetoric, often combined with overtly racial overtones. In Hungary, “far-right” Fidesz-KDNP candidates have decried “the heavy influence of Hungarian Jews in the culture and prosperity of the country.” (Freifeld, 2001) Anti-semitic rhetoric is also seen in French “far-right” politics, and was indeed foundational in the establishment of the National Front, now known as the National Rally. (France 24, 2018)

In Hungary, the Fidesz-KDNP enshrined its commitment “to promoting and safeguarding our heritage, our unique language, Hungarian culture, the languages and cultures of nationalities living in Hungary” (Constitute Project, 2011, p. 4) in its Constitution. In France, multiple-time National Rally presidential candidate and party head Marine Le Pen, an avowed Eurosceptic, has pledged “to slash France’s contributions to the EU” if elected. (Parker, 2022) In a 2019 speech, Le Pen concluded with an admonition to “turn our backs on all that made European peoples suffer, on policies that led to the economic and social failure of the EU… the European Union is dead.” (Marlowe, 2019)

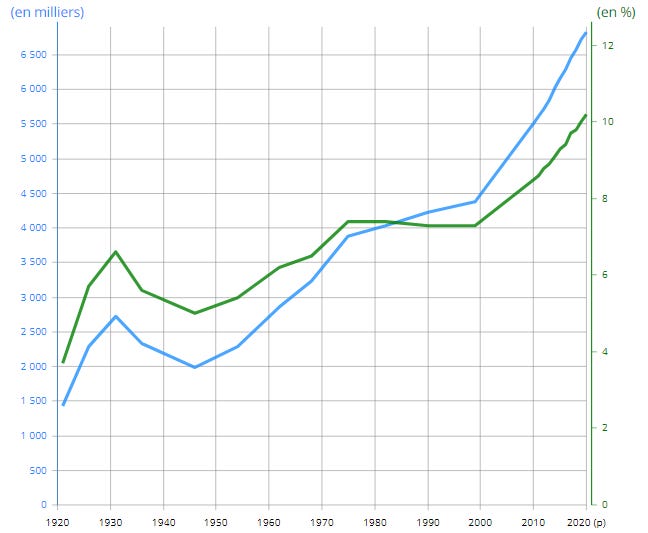

Transnational immigration rates rose steadily in each country from 1990-2020 as globalization accelerated in the 1980s. In France, immigrants as a share of the total population rose from around 4 percent in 1990 to over ten percent in 2020, a 250% increase.(L’Institut national de la statistique et des études économiques, 2021) At the same time, declining birth rates among non-immigrant French woman resulted in more than 19% of babies in France born to foreign-born women in 2017. (Volant, et al., 2019)

Historically “one of the most ethnically homogenous states” (Freifeld, 2001), Hungary experienced a 100% increase in transnational immigration rates from 2014 to 2019. At the same time, Hungary’s overall population has declined due to discrepancies between birth and death rates, (World Population Review, 2022) furthering the demographic impact of immigration to the country. In 2015, faced with calls to accept more immigrants to Hungary in the midst of a surge in migrants entering the EU, Orban claimed that “the stream of refugees would place an intolerable financial burden on European countries, adding that this would endanger the continent’s ‘Christian welfare states.'” (Reuter, 2015)