The Demonization of Slobodan Milosevic

This article was originally published in 2003.

U.S. leaders profess a dedication to democracy. Yet over the past five decades, democratically elected governments—guilty of introducing redistributive economic programs or otherwise pursuing independent courses that do not properly fit into the U.S.-sponsored global free market system—have found themselves targeted by the U.S. national security state. Thus democratic governments in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Cyprus, the Dominican Republic, Greece, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Syria, Uruguay, and numerous other nations were overthrown by their respective military forces, funded and advised by the United States. The newly installed military rulers then rolled back the egalitarian reforms and opened their countries all the wider to foreign corporate investors.

The U.S. national security state also has participated in destabilizing covert actions, proxy mercenary wars, or direct military attacks against revolutionary or nationalist governments in Afghanistan (in the 1980s), Angola, Cambodia, Cuba, East Timor, Egypt, Ethiopia, the Fiji Islands, Grenada, Haiti, Indonesia (under Sukarno), Iran, Jamaica, Lebanon, Libya, Mozambique, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Portugal, Syria, South Yemen, Venezuela (under Hugo Chavez), Western Sahara, and Iraq (under the CIA-sponsored autocratic Saddam Hussein, after he emerged as an economic nationalist and tried to cut a better deal on oil prices).

The propaganda method used to discredit many of these governments is not particularly original, indeed by now it is quite transparently predictable. Their leaders are denounced as bombastic, hostile, and psychologically flawed. They are labeled power hungry demagogues, mercurial strongmen, and the worst sort of dictators likened to Hitler himself. The countries in question are designated as “terrorist” or “rogue” states, guilty of being “anti-American” and “anti-West.” Some choice few are even condemned as members of an “evil axis.” When targeting a country and demonizing its leadership, U.S. leaders are assisted by ideologically attuned publicists, pundits, academics, and former government officials. Together they create a climate of opinion that enables Washington to do whatever is necessary to inflict serious damage upon the designated nation’s infrastructure and population, all in the name of human rights, anti-terrorism, and national security.

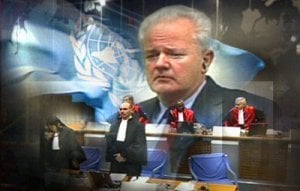

There is no better example of this than the tireless demonization of democratically-elected President Slobodan Milosevic and the U.S.-supported wars against Yugoslavia. Louis Sell, a former U.S. Foreign Service officer, has authored a book (Slobodan Milosevic and the Destruction of Yugoslavia, Duke University Press, 2002) that is a hit piece on Milosevic, loaded with all the usual prefabricated images and policy presumptions of the U.S. national security state. Sell’s Milosevic is a caricature, a cunning power seeker and maddened fool, who turns on trusted comrades and plays upon divisions within the party.

This Milosevic is both an “orthodox socialist” and an “opportunistic Serbian nationalist,” a demagogic power-hungry “second Tito” who simultaneously wants dictatorial power over all of Yugoslavia while eagerly pursuing polices that “destroy the state that Tito created.” The author does not demonstrate by reference to specific policies and programs that Milosevic is responsible for the dismemberment of Yugoslavia, he just tells us so again and again. One would think that the Slovenian, Croatian, Bosnian Muslim, Macedonian, and Kosovo Albanian secessionists and U.S./NATO interventionists might have had something to do with it.

In my opinion, Milosevic’s real sin was that he resisted the dismemberment of Yugoslavia and opposed a U.S. imposed hegemony. He also attempted to spare Yugoslavia the worst of the merciless privatizations and rollbacks that have afflicted other former communist countries. Yugoslavia was the only nation in Europe that did not apply for entry into the European Union or NATO or OSCE.

For some left intellectuals, the former Yugoslavia did not qualify as a socialist state because it had allowed too much penetration by private corporations and the IMF. But U.S. policymakers are notorious for not seeing the world the way purist left intellectuals do. For them Yugoslavia was socialist enough with its developed human services sector and an economy that was over 75 percent publicly owned. Sell makes it clear that Yugoslavia’s public ownership and Milosevic’s defense of that economy were a central consideration in Washington’s war against Yugoslavia. Milosevic, Sell complains, had a “commitment to orthodox socialism.” He “portrayed public ownership of the means of production and a continued emphasis on [state] commodity production as the best guarantees for prosperity.” He had to go.

To make his case against Milosevic, Sell repeatedly falls back on the usual ad hominem labeling. Thus we read that in his childhood Milosevic was “something of a prig” and of course “by nature a loner,” a weird kind of kid because he was “uninterested in sports or other physical activities,” and he “spurned childhood pranks in favor of his books.” The author quotes an anonymous former classmate who reports that Slobodan’s mother “dressed him funny and kept him soft.” Worse still, Slobodan would never join in when other boys stole from orchards—no doubt a sure sign of childhood pathology.

Sell further describes Milosevic as “moody,” “reclusive,” and given to “mulish fatalism.” But Sell’s own data—when he pauses in his negative labeling and gets down to specifics—contradicts the maladjusted “moody loner” stereotype. He acknowledges that young Slobodan worked well with other youth when it came to political activities. Far from being unable to form close relations, Slobodan met a girl, his future wife, and they enjoyed an enduring lifelong attachment. In his early career when heading the Beogradska Banka, Milosevic was reportedly “communicative, caring about people at the bank, and popular with his staff.” Other friends describe him as getting on well with people, “communal and relaxed,” a faithful husband to his wife, and a proud and devoted father to his children. And Sell allows that Milosevic was at times “confident,” “outgoing,” and “charismatic.” But the negative stereotype is so firmly established by repetitious pronouncement (and by years of propagation by Western media and officialdom) that Sell can simply slide over contradictory evidence—even when such evidence is provided by himself.

Sell refers to anonymous “U.S. psychiatrists, who have studied Milosevic closely.” By “closely” he must mean from afar, since no U.S. psychiatrist has ever treated or even interviewed Milosevic. These uncited and unnamed psychiatrists supposedly diagnosed the Yugoslav leader as a “malignant narcissistic” personality. Sell tells us that such malignant narcissism fills Milosevic with self-deception and leaves him with a “chore personality” that is a “sham.” “People with Milosevic’s type of personality frequently either cannot or will not recognize the reality of facts that diverge from their own perception of the way the world is or should be.” How does Dr. Sigmund Sell know all this? He seems to find proof in the fact that Milosevic dared to have charted a course that differed from the one emanating from Washington. Surely only personal pathology can explain such “anti-West” obstinacy. Furthermore, we are told that Milosevic suffered from a “blind spot” in that he was never comfortable with the notion of private property. If this isn’t evidence of malignant narcissism, what is? Sell never considers the possibility that he himself, and the global interventionists who think like him, cannot or will not “recognize the reality of facts that diverge from their own perception of the way the world is or should be.”

Milosevic, we are repeatedly told, fell under the growing influence of his wife, Mirjana Markovic, “the real power behind the throne.” Sell actually calls her “Lady Macbeth” on one occasion. He portrays Markovic as a complete wacko, given to uncontrollable anger; her eyes “vibrated like a scared animal”; “she suffers from severe schizophrenia” with “a tenuous grasp on reality,” and is a hopeless “hypochondriac.” In addition, she has a “mousy” appearance and a “dreamy” and “traumatized” personality. And like her husband, with whom she shares a “very abnormal relationship,” she has “an autistic relation with the world.” Worse still, she holds “hardline marxist views.” We are left to wonder how the autistic dysfunctional Markovic was able to work as a popular university professor, organize and lead a new political party, and play an active role in the popular resistance against Western interventionism.

In this book, whenever Milosevic or others in his camp are quoted as saying something, they “snarl,” “gush,” “hiss,” and “crow.” In contrast, political players who win Sell’s approval, “observe,” “state,” “note,” and “conclude.” When one of Milosevic’s superiors voices his discomfort about “noisy Kosovo Serbs” (as Sell calls them) who were demonstrating against the mistreatment they suffered at the hands of Kosovo Albanian secessionists, Milosevic “hisses,” “Why are you so afraid of the street and the people?” Some of us might think this is a pretty good question to hiss at a government leader, but Sell treats it as proof of Milosevic’s demagoguery.

Whenever Milosevic did anything that aided the common citizenry, as when he taxed the interest earned on foreign currency accounts—a policy that was unpopular with Serbian elites but appreciated by the poorer strata—he is dismissed as manipulatively currying popular favor. Thus we must accept Sell’s word that Milosevic never wanted the power to prevent hunger but only hungered for power. The author operates from a nonfalsefiable paradigm. If the targeted leader is unresponsive to the people, this is proof of his dictatorial proclivity. If he is responsive to them, this demonstrates his demagogic opportunism.

In keeping with U.S. officialdom’s view of the world, Sell labels “Milosevic and his minions” as “hardliners,” “conservatives,” and “ideologues”; they are “anti-West,” and bound up in “socialist dogma.” In contrast, Croatian, Bosnian, and Kosovo Albanian secessionists who worked hard to dismember Yugoslavia and deliver their respective republics to the tender mercies of neoliberal rollback are identified as “economic reformers,” “the liberal leadership,” and “pro-West” (read, pro-transnational corporate capitalist). Sell treats “Western-style democracy” and “a modern market economy” as necessary correlates. He has nothing to say about the dismal plight of the Eastern European countries that abandoned their deficient but endurable planned economies for the merciless exactions of laissez-faire capitalism.

Sell’s sensitivity to demagoguery does not extend to Franco Tudjman, the crypto-fascist anti-Semite Croat who had nice things to say about Hitler, and who imposed his harsh autocratic rule on the newly independent Croatia. Tudjman dismissed the Holocaust as an exaggeration, and openly hailed the Croatian Ustashe Nazi collaborators of World War II. He even employed a few aging Ustashe leaders in his government. Sell says not a word about all this, and treats Tudjman as just a good old Croatian nationalist. Likewise, he has not a critical word about the Bosnian Muslim leader Alija Izetbegovic. He comments laconically that Izetbegovic “was sentenced to three years imprisonment in 1946 for belonging to a group called the Young Muslims.” One is left with the impression that the Yugoslav communist government had suppressed a devout Muslim. What Sell leaves unmentioned is that the Young Muslims actively recruited Muslim units for the Nazi SS during World War II; these units perpetrated horrid atrocities against the resistance movement and the Jewish population in Yugoslavia. Izetbegovic got off rather lightly with a three-year sentence.

Little is made in this book of the ethnic cleansing perpetrated against the Serbs by U.S.-supported leaders like Tudjman and Izetbegovic during and after the U.S.-sponsored wars. Conversely, no mention is made of the ethnic tolerance and diversity that existed in President Milosevic’s Yugoslavia. By 1999, all that was left of Yugoslavia was Montenegro and Serbia. Readers are never told that this rump nation was the only remaining multi-ethnic society among the various former Yugoslav republics, the only place where Serbs, Albanians, Croats, Gorani, Jews, Egyptians, Hungarians, Roma, and numerous other ethnic groups could live together with some measure of security and tolerance.

The relentless demonization of Milosevic spills over onto the Serbian people in general. In Sell’s book, the Serbs are aggrandizing nationalists. Kosovo Serbs demonstrating against mistreatment by Albanian nationalists are described as having their “bloodlust up.” And Serb workers demonstrating to defend their rights and hard won gains are dismissed by Sell as “the lowest instruments of the mob.” The Serbs who had lived in Krajina and other parts of Croatia for centuries are dismissed as colonial occupiers. In contrast, the Slovenian, Croatian, and Bosnian Muslim nationalist secessionists, and Kosovo Albanian irredentists are simply seeking “independence,” “self-determination,” and “cultural distinctiveness and sovereignty.” In this book, the Albanian KLA gunmen are not big-time drug dealers, terrorists, and ethnic cleansers, but guerrilla fighters and patriots.

Military actions allegedly taken by the Serbs, described in the vaguest terms, are repeatedly labeled “brutal,” while assaults and atrocities delivered upon the Serbs by other national groups are more usually accepted as retaliatory and defensive, or are dismissed by Sell as “untrue,” “highly exaggerated,” and “hyperventilated.” Milosevic, Sell says, disseminated “vicious propaganda” against the Croats, but he does not give us any specifics. Sell does provide one or two instances of how Serb villages were pillaged and their inhabitants raped and murdered by Albanian secessionists. From this he grudgingly allows that “some of the Serb charges . . . had a core of truth.” But he makes nothing more of it.

The well-timed, well-engineered story about a Serbian massacre of unarmed Albanians in the village of Racak, hyped by U.S. diplomat and veteran disinformationist William Walker, is wholeheartedly embraced by Sell, who ignores all the contrary evidence. An Associated Press TV crew had actually filmed the battle that took place in Racak the previous day in which Serbian police killed a number of KLA fighters. A French journalist who went through Racak later that day found evidence of a battle but no evidence of a massacre of unarmed civilians, nor did Walker’s own Kosovo Verification Mission monitors. All the forensic reports reveal that almost all of the forty-four persons killed had previously been using fire arms, and all had perished in combat. Sell simply ignores this evidence.

The media-hyped story of how the Serbs allegedly killed 7,000 Muslims in Srebrenica is uncritically accepted by Sell, even though the most thorough investigations have uncovered not more than 2,000 bodies of undetermined nationality. The earlier massacres carried out by Muslims, their razing of some fifty Serbian villages around Srebrenica, as reported by two British correspondents and others, are ignored. The complete failure of Western forensic teams to locate the 250,000 or 100,000 or 50,000 or 10,000 bodies (the numbers kept changing) of Albanians supposedly murdered by the Serbs in Kosovo also goes unnoticed.

Sell’s rendition of what happened at Rambouillet leaves much to be desired. Under Rambouillet, Kosovo would have been turned into a NATO colony. Milosevic might have reluctantly agreed to that, so desperate was he to avoid a full-scale NATO onslaught on the rest of Yugoslavia. To be certain that war could not be avoided, however, the U.S. delegation added a remarkable stipulation, demanding that NATO forces and personnel were to have unrestrained access to all of Yugoslavia, unfettered use of its airports, rails, ports, telecommunication services, and airwaves, all free of cost and immune from any jurisdiction by Yugoslav authorities. NATO would also have the option to modify for its own use all of Yugoslavia’s infrastructure including roads, bridges, tunnels, buildings, and utility systems. In effect, not just Kosovo but all of Yugoslavia was to be subjected to an extraterritoriality tantamount to outright colonial occupation.

Sell does not mention these particulars. Instead he assures us that the request for NATO’s unimpeded access to Yugoslavia was just a pro forma protocol inserted “largely for legal reasons.” A similar though less sweeping agreement was part of the Dayton package, he says. Indeed, and the Dayton agreement reduced Bosnia to a Western colony. But if there was nothing wrong with the Rambouillet ultimatum, why then did Milosevic reject it? Sell ascribes Milosevic’s resistance to his perverse “bunker mentality” and his need to defy the world.

There is not a descriptive word in this book of the 78 days of around-the-clock massive NATO bombing of Yugoslavia, no mention of how it caused the loss of thousands of lives, injured and maimed thousands more, contaminated much of the land and water with depleted uranium, and destroyed much of the country’s public sector industries and infrastructure-while leaving all the private Western corporate structures perfectly intact.

The sources that Sell relies on share U.S. officialdom’s view of the Balkans struggle. Observers who offer a more independently critical perspective, such as Sean Gervassi, Diana Johnstone, Gregory Elich, Nicholas Stavrous, Michel Collon, Raju Thomas, and Michel Chossudovsky are left untouched and uncited. Important Western sources I reference in my book on Yugoslavia offer evidence, testimony, and documentation that do not fit Sell’s conclusions, including sources from within the European Union, the European Community’s Commission on Women’s Rights, the OSCE and its Kosovo Verification Mission, the UN War Crimes Commission, and various other UN commissions, various State Department reports, the German Foreign Office and German Defense Ministry reports, and the International Red Cross. Sell does not touch these sources.

Also ignored by him are the testimonies and statements of members of the U.S. Congress who visited the Balkans, a former State Department official under the Bush administration, a former deputy commander of the U.S. European command, several UN and NATO generals and international negotiators, Spanish air force pilots, forensic teams from various countries, and UN monitors who offer revelations that contradict the picture drawn by Sell and other apologists of U.S. officialdom.

In sum, Sell’s book is packed with discombobulated insider details, unsupported charges, unexamined presumptions, and ideologically loaded labeling. As mainstream disinformation goes, it is a job well done.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Michael Parenti’s recent books are To Kill a Nation: The Attack on Yugoslavia (Verso), and The Terrorism Trap: September 11 and Beyond (City Lights). His latest work, The Assassination of Julius Caesar: A People’s History of Ancient Rome has been nominated for a Pulitzer Prize. © Copyright M Parenti 2003 For fair use only/ pour usage équitable seulement.

Featured image is from One Voyce of the World