Building a Definition of Development

The idea of development itself, its definition, and even the method we use for defining it, would be a good place to begin toward discovering its potential in our lives. We cannot rely on any single, or even ten, definitions. We need to look at the full range of literature that arose following the end of World War II, decolonization, and reconstruction from when international development spawned in our era. How has development been defined across the decades?

One of the ways this information can be organized is by looking at the explanations–some concise, some longer–of what development is, and taking those few sentences and putting them into a file, building a database of development descriptions. This process gave me several hundreds of pages from several thousands of books or authors that can help one come to an understanding of what is development.

The next step is to break down the definitions into their components. You have a box for development as it relates to economics. Another relates to social aspects. Still another is about the political side of the issue, and another is about geography. Other components will include change, growth, and process. When you have built a database of information and broken the concept down into its elements, you are then in the position of defining the term based on the range of its basic elements.

You can extend this method to other aspects of your life and work, where I hope you find the most passion. Defining the terms will be essential to creating a foundation for your research, investigation, analysis, understanding, teaching, and training. In my own investigation, absorbing all possible literature on the development field that emerged from the 1950s up until 2011, at which time most of my energies transitioned from academic study to development practice in Morocco, I can share what I gathered. One result of dedicated study can be the formulation of new definitions, created by drawing from all of the “baskets” of broken down and organized parts, and then reassembled into working definitions.

What we find with all of these words–development, empowerment, sustainability, participation–is that there are great differences and lack of consensus in their meaning, with entirely different emphases, depending on the context. There are also some other words–like progress, change, movement, mobilization, action, unpredictable, and multi-dimensional that reappear when we discuss development. Lack of predictability does not mean uncontrollable or unmanageable, but rather requiring flexibility or the ability to adapt with ever-changing circumstances.

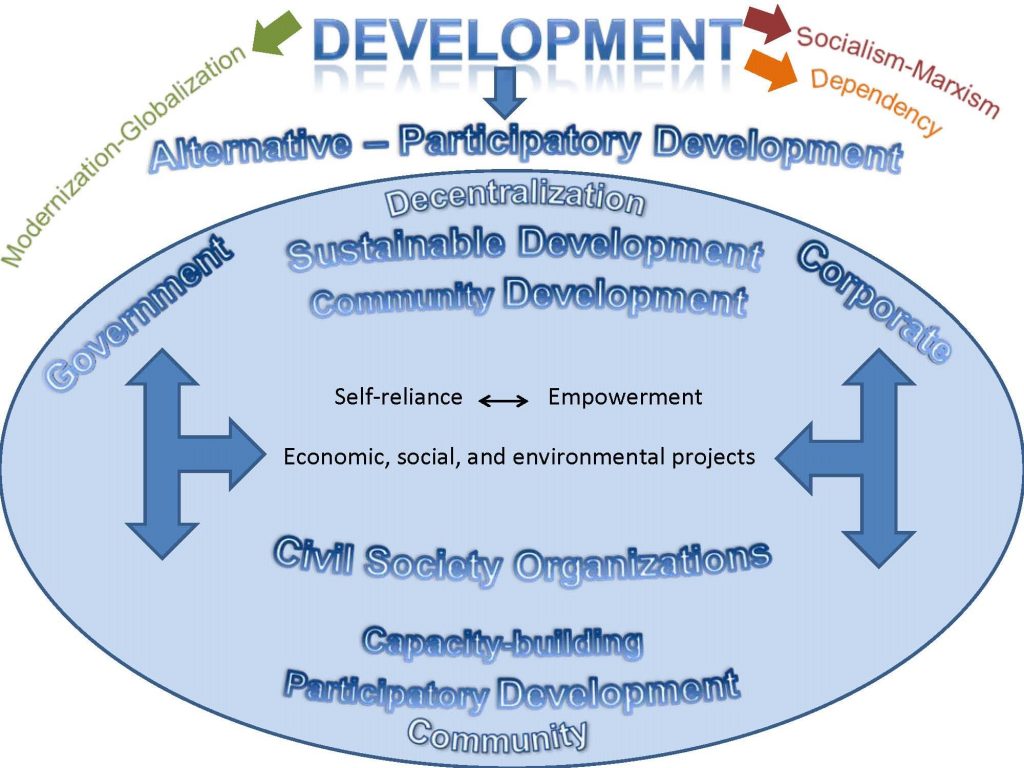

A model of the Alternative-Participatory Development social system (Yossef Ben-Meir, 2009)

What do we mean when we say “multi-dimensional”? What are these dimensions? Economic, environmental, cultural, social, political, technological, financial, historical, and physical-ecological–these have all been identified as elements of development, recognizing that they touch every aspect of community life or the totality of human life. Development experiences also identify a spiritual aspect, connecting to the universal, recognizing that the impact of development is also internal and perceptional. These dimensions surround our community lives and are within the fabric of our relating to one another.

From the early decades to today, “modernization” has been the underlying perspective for approaching development. All societies experience or need to experience this espoused linear progression from point A to point B as part of their development process. The agricultural economy needs to be productive to the point where it can feed a growing urban population, so that people in the cities can manufacture and have industry. If we are in Morocco or anywhere else, modernization’s progression–at least according to its own view–is necessary for development.

When we talk about development that doesn’t support this model–it’s not A, B, C, D, E for everyone. What works for you might not work for us and might actually hurt us, take away our autonomy, and won’t let us build our economy based on our choices and capacity and agricultural opportunity. Not taking into consideration our geographical and environmental situations, our history, our culture, our traditions, strict modernization is often a source of our poverty. Development which tries to readdress this rigidity is labeled “alternative”, controversial, or even politically contradictory.

Our definition of development must include growth and expansion and meeting human needs. There are, however, profound differences among different societies on how those things are achieved and what the nature, quality, and characteristics of the growth look like. This is why a single definition is so difficult to land on. It dooms us to not be fully adequate in our definition. Forms of development can be conflictual. We can’t have full industrialization in developing countries based on products that are in demand in developed countries and expect the same outcomes on all sides of the exchanges. The modernization model may create a cost borne by developing/less-industrial countries because they will only grow as a reflection of demand in the developed ones.

From the birth of development, there has always been an alternative approach, rejecting external control that mainstream prescriptions bring and instead emphasizing internally strengthening (and diversifying) people-driven change. Today, it is the norm to advance people’s participation–in Morocco, it is the law–but that point of view did not used to be mandated and was distrusted by those in the mainstream who believed it was putting collectives of people in positions to make decisions they were not equipped to make. The outcome and what public participation would mobilize was feared and distrusted.

Who is to benefit from development and enhanced quality of life through mobilization, action, change, and a multi-dimensional process improving upon all aspects of human life? The goal is all or the majority of people, but particularly the people who experience poverty and marginalization. We will always have to make choices because budgets are never endless. However, when making choices, we focus on people who are disenfranchised, disadvantaged, and remote–the individual and the collective. Not just in Morocco, but around the world, most poverty is concentrated in rural areas, and within these places, typically the highest rate impoverishment is in mountainous and dry regions.

So, what definition of development have we come to after reviewing literature, breaking down into parts, and reconfiguring these elements into something workable? It is a process that considers in its planning, economic, political, institutional, cultural, environmental and technological factors to achieve its goal of generating benefits in these areas directed at all or the majority of people, especially those who experience poverty.

If we go through this process together, across our localities, we will be in a superb position to manage public health in a pandemic. We will be in a position to encourage calm dialogue in the face of terrible unrest and unfairness. We will understand how we may effectively govern and campaign to govern, to devise infrastructure investments for maximum community-level return and widely shared management and benefits, to guide our trade relationships emphasizing self-reliance, regional bloc markets, and global engagement, and to address the root causes of people’s dissatisfying work and interconnectivity with each other. To best face the time we’re in, there is no greater immediate and long-term urgency than the process of development requiring inclusion.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Dr. Yossef Ben-Meir is a sociologist and President of the High Atlas Foundation, a U.S.-Moroccan non-for-profit organization dedicated to sustainable development in Morocco.