Declassified Documents: 1997 Mapiripán Massacre: Coordinated in advance with Colombian Army

Photo above: Carlos Castaño and members of the United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC).

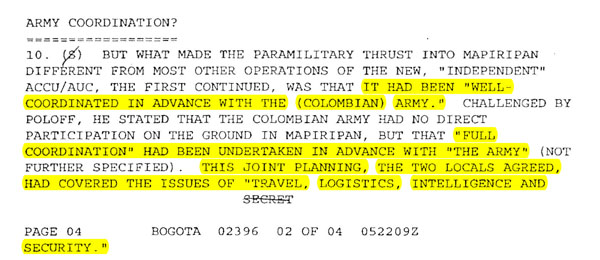

The massacre was “well-coordinated in advance” with the Colombian Army.

Colombia’s Mapiripán massacre was “well-coordinated in advance” with the Colombian Army, according to confidential paramilitary sources, one of which the U.S. Embassy believed had “participated directly in the planning” of the killings. The new disclosures are the first from a fresh set of declassified diplomatic cables on the Mapiripán case released at the end of last week by the State Department’s Appeals Review Panel on the15th anniversary of the massacre.

If this “blunt admission” of Army complicity in the Mapiripán massacre was correct, an Embassy official observed, “then both of the key paramilitary operations which most directly affected U.S.-assisted counter-narcotics operations in the Guaviare region in 1997 had been conducted with the foreknowledge and facilitation by members of the Colombian Army.” The other “operation” was the October 1997 massacre at Miraflores, which, like Mapiripán, was then an important narcotics trafficking hub in Colombia’s eastern plains.

It’s taken the State Department 15 years to declassify what it knew only 18 months after those dark days: that the Mapiripán massacre was likely the result of an Army-paramilitary conspiracy that went “well beyond” the units and individuals that have been implicated so far. The document suggests that the previous convictions in the case—which mostly involve junior officers and crimes of omission—are merely the tip of the iceberg.

A few days ago, we published a 2003 letter in which the State Department claimed—six years after the fact—that the Colombian military had tried to “cover up” the massacre, in which dozens were brutally killed by illegal paramilitary forces brought in from northern Colombia. These new documents, most of which are from 1997-1999, go a long way toward explaining how they arrived at that conclusion.

The Mapiripán case remains one of the most critical, and in many ways unresolved, massacre cases in recent Colombian history. In a country that has seen far too many human rights atrocities, no single case is as central the story of paramilitary expansion in Colombia as Mapiripán. The operation was the first major projection of paramilitary power outside of northern Colombia, where the rightist militia forces consolidated their hold on power in the 1980s and 1990s.

The Embassy report did not identify the two “public, well-known” individuals from the paramilitary stronghold of Montería, Córdoba, who provided the information, but said that “we have reason to believe that one of the two … has participated directly in the planning of AUC military operations – to include, based on a discussion with POLOFF [the Embassy’s Political Officer], Mapiripán.”

The United Self-Defense Forces of Colombia (AUC), led by Carlos Castaño, was the country’s top paramilitary organization at the time. Castaño, now deceased, admitted that the AUC was behind the massacre, warning that there would be “many more Mapiripáns.” Several other paramilitary members, including top commander Salvatore Mancuso, have also been convicted for plotting the massacre.

The Embassy judged the paramilitary interlocutors to be “most credible,” according to the cable, which was approved by U.S. Ambassador Curtis Kamman. “We know of no reason for them to deviate from their boasting of the AUC’s full-fledged independence,” the Embassy said, “other than their desire for the USG [U.S. government] to understand correctly what had transpired eighteen months ago.” The AUC, under Carlos Castaño, wanted “political legitimacy,” according to the cable, and “some degree of recognition from the USG—which they have consistently failed to get.” By raising the question of Mapiripán, the report continued, the Embassy official who interviewed the sources had “put the two in a position of either having to lie to us, or to come clean.”

Mapiripán “was quite different” from other paramilitary operations, the paras told the POLOFF—“a special case.” At least five different paramilitary fronts participated in the massacre with “full coordination” from the Army, including “travel, logistics, intelligence and security.” The conspiracy went “well beyond” the two sergeants who had been arrested for facilitating the paras’ arrival at a joint military/police airfield in San José del Guaviare.

Mapiripán was actually “a well-coordinated counter-narcotics operation,” the sources said, the goal of which was to strike “a coordinated blow” against the left-wing FARC guerrillas, “by targeting the key money-movers who buy and sell cocaine for the FARC.” The operation was a “success,” according to one of the paramilitary contacts, in that it had damaged “the FARC’s ability to move both money and cocaine in the region.”

The paramilitary sources also “did not contradict” the Embassy official’s suggestion that such a “well-coordinated” operation would have also involved the collaboration of Army elements from their point of departure in Urabá.

In recent years, the former commander of the Army brigade in Urabá at the time of the Mapiripán massacre, Gen. Rito Alejo del Río, has come under scrutiny for alleged “systematic” reliance on paramilitary forces to strike at guerrillas in northern Colombia. Now on trial in a separate human rights case, Del Río has never been charged in connection to Mapiripán, despite that fact that several former paramilitaries and at least one of the military officers convicted in the case have identified Del Río as one of the intellectual authors.

It’s notable enough that an Embassy official had direct, face-to-face contact with one of the presumed authors of the Mapiripán massacre, but the real news here is the paras’ “blunt admission” that they had the “full coordination” of the Army, from beginning to end. This suggests that the Mapiripán conspiracy was much wider and deeper than previously thought.

From the start, Mapiripán was unique as much for its sheer brutality as for what appeared to be the clear involvement of Colombian security forces. Most importantly, the massacre put the newly-formed AUC on the map and established the model by which AUC paramilitary forces, aided by elements of the security forces, would swoop into an important narcotics-producing area, assassinate scores of perceived guerrilla supporters and take over the drug trade.