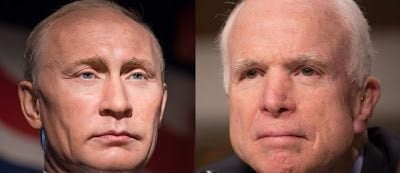

“Dear Vlad, Is It Something I Said?”: The Fierce Rivalry Between John McCain and Vladimir Putin

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

The ferocious sense of enmity that existed between John McCain, the late US Senator, and Vladimir Putin, the President of the Russian Federation, was quite palpable. While McCain was never an occupant of the White House, he was nonetheless a very prominent and permanent feature in the Cold War which developed during the 2000s. He was always an influential figure operating openly as well as covertly during the defining events which have shaped relations between both countries: Georgia, Libya, Syria, Ukraine, as well as the machinations involved in first prising Montenegro from Serbia and then removing it from the Russian orbit of influence. Where some saw McCain as a key advocate for the export of American liberty to areas of the world afflicted by tyranny, others see Putin as the central figure in trying to arrest the destructive attempts by the United States to impose a global imperium after the fall of the Soviet Union. An exploration of the rivalry between both men, one an avowed America patriot and the other a Russian nationalist, provides a key thread in charting, as well as understanding why the United States and Russia have become dangerously at loggerheads in recent times.

The deep-seated mutual loathing between John McCain and Vladimir Putin was a well known and played out over many years. It is perhaps correct to state that McCain’s malice often came out in a more forthright manner. For instance, soon after it was announced in 2011 that Putin would again be running for the office of President of the Russian Federation, McCain issued a tweet saying that Russia faced its own Arab Spring”. While many implied that McCain was forecasting that Putin would perish in a similar way to the former Libyan leader, Muammar Gaddafi, Putin opined that McCain’s comment had been directed at Russia in general. But he could not resist retorting that McCain had evidently “lost his mind” while being held captive by the North Vietnamese. To that barb, McCain mockingly responded:

“Dear Vlad, is it something I said?”

By all accounts, both men only met once at the Munich Security Conference in 2007. But they often appeared to be at each other’s throats. And this was not limited to intermittent threats and diatribes issued on social media, in speeches or at news conferences. Their hostility was an almost permanent feature in the discourse associated with the series of geopolitical confrontations that have occured over the past decade between the United States and the Russian Federation. The conflicts in Georgia, Libya, Syria and Ukraine, as well as the accession of Montenegro to NATO, all reflected the fundamental ideological division between them.

McCain’s consistent support for American interventionism, predicated on a belief in its exceptionalism, had the objective of maintaining US global leadership, while Putin’s nationalism was consistent with his objective of reestablishing multi-polarity. While McCain’s stance is characterised in positive terms as an insistence that ‘freedom’ should prevail over ‘tyranny’, Putin’s position is often portrayed by his supporters as one that is boldly resisting the imposition of American hegemony and even what is referred to as a ‘globalist agenda’.

Both men accused each other of fomenting a new ‘Cold War’. To McCain, Putin was the leader of a revanchist Russian state intent on reclaiming the territories lost after the breakup of the Soviet Union in the early 1990s. In 2008, during his acceptance speech after being nominated as presidential candidate at the Republican Party Convention, McCain lashed out at Putin and the Russian oligarchs who, “rich with oil wealth and corrupt with power … (are) reassembling the old Russian Empire.”

Putin had, after all, in a speech three years earlier, bemoaned the collapse of the USSR as “the greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the 20th century.” As John Bolton put it in the aftermath of the crisis sparked by the removal of Viktor Yanukovych from power in 2014:

“It’s clear (Putin) wants to re-establish Russian hegemony within the space of the former Soviet Union. Ukraine is the biggest prize, that’s what he’s after. The occupation of the Crimea is a step in that direction.”

Putin, on the other hand, considered McCain to be the promoter-in-chief of the American militarism that had germinated in the post-Cold War era. Those who support this view posit that American policy has, since the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, being informed by two specific geopolitical doctrines inspired respectively by Paul Wolfowitz and Zbigniew Brzeziński. The Wolfowitz Doctrine holds that in the aftermath of the demise of the Soviet Union, the United States must prevent the rise of another power capable of competing with it globally in the military and economic spheres, while the Brzeziński Doctrine provides that Russia should be intimidated while the US works towards its dismantling; the objective being to reduce Russia to a state of vassalage, with its role being restricted to that of supplying the energy needs of the West.

When McCain sneered at Russia for being, in his words, “a gas station masquerading as a country”, he was not merely referring to Russia’s dependence on its oil and gas revenues for most of its national revenue. He was also hinting at the outcome prescribed by Brzeziński: Russia’s has no valid role in the world other than to pliantly provide its energy resources. It had no business opposing the United States in its god-given right to dominate the world.

During an interview in which McCain’s anti-Russian animus was discussed, Putin acknowledged that Russia’s possession of nuclear weapons was the decisive factor which enabled it to “practise independent politics”. In other words, having a nuclear capability, unlike those countries that have been destroyed by American intervention, gave Russia the ability to resist what he believed to be the aggressive foreign policy championed by the likes of McCain.

From the Russian perspective, Western animosity towards Russia and the incessant campaign by the Western media to demonise Putin is not based on heartfelt concerns about human rights and democracy, but is predicated on the fact that he brought to an end the wholesale plunder of Russia’s resources by Western interests during the presidency of Boris Yeltsin. Putin is also reviled for having the temerity to obstruct the American programme of effecting regime change in Syria as it did in Iraq and Libya and hopes to finish off by with Iran. The conduct of John McCain, and his attitude towards Putin, has been emblematic of this animosity.

When war broke out between Russia and Georgia in 2008. Putin accused McCain of having instigated the conflict in order to bolster his chances during his presidential run against Barack Obama.

“The suspicion arises”, Putin said, “that someone in the United States especially created this conflict to make the situation tenser and create a competitive advantage for one of the candidates fighting for the post of US president.”

McCain’s comment that the conflict had been mistakenly instigated by Georgia’s then president, Mikheil Saakashvili, did not impress Putin whose reading of events was that Georgia’s attack on South Ossetia had been encouraged by NATO.

In other conflicts where Russian interests were at stake, McCain was at the forefront. While NATO’s 2011 intervention in Libya had been permitted by UNited Nations Resolution 1973, a decision based on the ‘Right to Protect’ doctrine, Putin, who at the time was serving as prime minister, bitterly regretted President Dmitri Medvedev’s decision to support the resolution. Referring to it as “a medieval call for a crusade”, Putin correctly sensed what would transpire because the resolution permitted the use of air strikes. Gaddafi was overthrown and in the process lynched by Islamist forces that had been trained and supported by NATO countries.

John McCain had been a key voice in calling for US-intervention. He had gone to the city of Benghazi, a stronghold of the anti-Gaddafi insurgents where he walked around the streets and referred to the rebels as “heroic”. A disgusted Putin complained that

“When the so-called civilised community, with all its might pounces on a small country, and ruins infrastructure that has been built over generations – well, I don’t know, is this good or bad? I do not like it.”

He was also mindful that Russia stood to lose $4 billion in arms contracts with the Gaddafi government, and would doubtless have concurred with the protest issued by the then serving ambassador in Tripoli that Medvedev’s inaction by not blocking the resolution and thereby endangering the military contracts had amounted to a “betrayal of Russia’s interests.”

A few years later, while Libya functioned as a failed state, McCain would make another visit during which he gave an honour to Abdel Hakim Belhaj, a prominent Islamist leader of the insurgency. [“former” Libya Islamic Fighting Group linked to Al Qaeda]

McCain was also a visible presence in Ukraine during the Maidan protests that led to the overthrow of the government of Viktor Yanukovytch in February 2014. As in Libya, he walked the streets of Kiev. He addressed crowds and declared that Ukraine’s destiny lay with Europe. It was of course a plea to Ukraine to jettison itself outside the orbit of Russia. And while McCain’s actions in Kiev were viewed by his supporters as being in keeping with his resolve to expand the frontiers of liberty, others offered a different interpretation. According to George Friedman, the founder and CEO of Strafor, an American geopolitical intelligence platform and publisher which has been referred to as “The Shadow CIA”, the removal of Yanukovych “was the most blatant coup in history.”

Using neo-Nazi and ultra-nationalist groups such as Pravy Sektor as ‘street muscle’, the American intelligence and the State Department facilitated a change of government, an enterprise that was captured in part by phone taps which revealed Victoria Nuland, the Under Secretary of State for Eastern European and Eurasian Affairs, naming those who would hold key offices of state after Yanukovych’s ouster.

McCain, like Nuland, had met with a range of anti-Russian Ukrainian figures including Oleh Tyahnybok, the leader of the far right Svoboda Party, with whom he was photographed.

Meanwhile in Moscow, Putin calculated that the installation, by the Americans, of an ultra-nationalist and Russophobic regime on Russia’s doorstep imperilled Russia’s national security. So in order to secure its continued access to the Mediterranean Sea through one of its only warm water parts where its Black Sea Fleet resided, Putin set in motion the train of events which would lead to a referendum and the re-absorption of Crimea in Russia.

McCain denounced Putin’s action as illegal, and which was part of Putin’s objective of restoring Russia on the borders of the Soviet Union. In a BBC interview, he even compared Putin’s policy towards Crimea to those taken by Adolf Hitler.

He also led the calls for sanctions to be imposed on Russia. One of Putin’s responses was impose sanctions on McCain, an action to which he responded by tweeting:

“I’m proud to be sanctioned by Putin – I’ll never cease in my efforts (and) dedication to freedom (and) independence of Ukraine, which includes Crimea.”

McCain was active in another theatre where American and Russian interests collided. In Syria, he did not stop at calling for a more direct course of action from the United States aimed at overthrowing Bashar al-Assad. In December 2013, he visited insurgents -announced as belonging to the “Free Syrian Army”- who he described as “brave fighters who are risking their lives for freedom”. Both designations were untrue. The “freedom fighters”, more accurately defined by the Syrian government as “terrorists”, were like the rebels who McCain met in Benghazi: insurgents with an Islamist agenda.

The ‘Free Syrian Army’ was a largely non-existent militia formed by the Western powers which failed to grow into the large army that was envisaged. Moreover, many groups which met Western representatives such as McCain often announced themselves as being part of the ‘Free Syrian Army’, but reverted back to their true identities which more often than not were jihadist militias bearing an allegiance to al-Qaeda.

This modus operandi was alluded to by Putin in his speech to the UN General Assembly in September 2015 when announcing a more direct form of intervention in the Syrian conflict:

“First, they are armed and trained and then they defect to the so-called Islamic State. Besides, the Islamic State itself did not just come from nowhere. It was also initially forged as a tool against undesirable secular regimes.”

The destruction of Syria sought by McCain was predicated on the neoconservative policy of removing the leaders of those Arab states, most of them secular, who were resistant to Israel’s regional hegemony. The refusal of Assad to participate in building a gas pipeline supplying energy from pro-Western states in the Gulf also played a part in the decision of the United States to arm Islamist proxies.

But Russian intervention, in concert with the efforts of Iran and Hezbollah, has enabled the Syrian Army to reclaim most of the Syrian territory that had been taken by groups such as the ‘al Nusra Front’ and the ‘Islamic State’. It was a turn of events which angered and frustrated McCain who referred to President Barack Obama’s policy as “toothless”. He advocated a strategy of creating “safe zones”, ostensibly to protect Syrian civilians from what he termed “violations by Mr. Assad, Mr. Putin and extremist forces”. The strategy of ‘safe zones’, a technique used by NATO when confronting and destroying the Libyan army in 2011, was acknowledged by a declassified Defense Intelligence Agency (DIA) document as a technique through which the creation of independent territorial entities could be created, in the case of Syria, a Salafist emirate in its eastern region.

But if the goal of regime change in Syria, so vigorously encouraged by McCain, was frustrated by Putin, his efforts in enabling the state of Montenegro to be first prised from Serbia and then granted NATO membership status doubtlessly succeeded in doing the same to Putin.

McCain’s actions in helping to enable the Russian oligarch Oleg Deripaska to buy up Montenegro’s aluminium industry, perplexed observers who accused him of hypocrisy in allowing a man, who at the time was dubbed ‘Putin’s Oligarch’, to control the aluminum-dependent Montenigrin economy. Deripaska’s supposed closeness to Putin at the time convinced some that McCain was actually working for his arch-enemy.

But nothing could be further from the truth. Montenegro was being bought up en masse by Western financiers such as Nathaniel Rothschild and many of its leaders were being paid off to seek independence from Serbia as a prelude to it joining the Atlantic Alliance. When Senator Rand Paul blocked the initial Senate conferment on ratification of Montenigrin accession, McCain took the floor and furiously accused Paul of being an agent of Vladimir Putin.

Repeatedly invoking the name of Putin, McCain warned:

“If there is objection, you are achieving the objectives of Vladimir Putin… I have no idea why anyone would object to this, except that I will say, if they object: they are now carrying out the desires and ambitions of Vladimir Putin.”

McCain had played his part in an elaborate plot aimed at checking Russian interests. Placing Montenegro into the Western sphere succeeded in denting Russian influence in an area which is traditionally linked to Russia because of the Christian Orthodox faith of its Slav inhabitants. The subsequent drilling for oil off the pristine Adriatic coast is calculated to nullify Russian designs on a South Stream pipeline.

McCain revelled in the news that a coup, allegedly planned to occur on the day of parliamentary elections in October 2016, had been foiled. Its participants were claimed to have been Kremlin-backed Serbian and Russian nationalists who were acting in a last ditch attempt to prevent the country’s accession to NATO. McCain took to the senate floor to make a speech (which he later converted into a newspaper column) to denounce Putin.

Claiming that “Vladimir Putin’s Russia is on the offensive against Western democracy”, McCain linked the Montenigrin plot to the alleged Russian interference in the last American presidential elections and others by writing that it was “just one phase of Putin’s long-term campaign to weaken the United States, to destabilise Europe, to break the NATO alliance, to undermine confidence in Western values, and to erode any and all resistance to his dangerous view of the world.”

While doubts have been raised concerning the existence of a serious plot because the alleged ring appeared to be composed of a motley band emanating from disparate and innocuous trades and professions -some of whom were elderly and others who reneged on their confessions- Montenegrin accession remains a blow to Russian interests.

McCain often placed the blame of a US-Russian Cold War squarely on Putin’s shoulders. When in 2007, Putin complained that the US was seeking to establish a “uni-polar” world, it was McCain who led the Western retort by accusing Putin of presiding over an autocratic regime whose “actions at home and abroad conflict so fundamentally with the core values of Euro-Atlantic democracies.” After the conference, the BBC reported that “in the corridors there were dark mutterings by some about a new Cold War”.

If there is any truth to John McCain’s assertion that Vladimir Putin was treating global politics as a “Cold War Chessboard”, then his involvement in the Montenigrin intrigue demonstrated that he was a willing player in this ‘Great Game’ of international brinkmanship. Further, McCain’s repeated accusation of Putin being the initiator of the disharmonious state of relations between Russia and the United States is disputed by experts such as Stephen Cohen, a professor emeritus of Russian studies and politics at New York University and Princeton. Cohen convincingly argues that Putin’s actions on the world stage in Georgia, Ukraine and Syria have been reactive and not proactive.

We have the word of McCain himself to confirm this about the Russo-Georgian conflict which he claimed had been “a mistake” initiated by Mikheil Saakashvili. And Putin’s withdrawal of Russian forces from Georgian territory, which had long been a province of both Russian and Soviet empires, presents evidence that he is not working towards a ‘Tanaka Memorial’-style plan of territorial expansion.

The same may be said of Ukraine, in regard to which Putin refused the pleas of Russian ultranationalists to invade and annexe the Russian-speaking eastern part of the country. His refusal led to allegations of ‘weakness’ from hardliners. The Russian armed forces, of course, had the capability of invading and conquering the whole of Ukraine. Putin’s measured response in limiting his response to American actions such as reabsorbing Crimea also applies to Syria where Russian intervention came after much prevarication by a chief of state who unsurprisingly worried about sending the Russian military into a quagmire of the sort which the Soviet Union became embroiled in the 1980s.

McCain, on the other hand, supported the idea of US military intervention across the globe. He is on record as supporting virtually every US-led or US-backed overt or covert military action before and after the events of September 11th 2001. His support for American militarism and his prominence as a high-ranking US senator intimately involved in national security affairs made his rivalry with Vladimir Putin something of an inevitability. In many ways, McCain embodies the American half of the new Cold War because his longevity as a senator provided the basis for his continuous presence in the realm of national security and foreign policy. Presidents came and contended with Vladimir Putin, but McCain remained an ever present figure until his death.

McCain appeared to be as convinced about the ineluctable force of evil Vladimir Putin represented as he was of the sanctity of the wars he made in the cause of spreading American liberty. When Donald Trump responded to an interviewer’s allegation that Putin murdered his political adversaries by inquiring whether the interviewer thought “our country’s so innocent”, McCain exploded on the senate floor and insisted that there was no moral equivalence between the United States and “Putin’s Russia”. Loudly tapping on the lectern he boomed:

“I repeat, there is no moral equivalence between that butcher and thug and KGB colonel and the United States of America.”

Putin’s feelings about McCain are no less gentle. He once specifically alluded to McCain having “civilian blood on his hands” during his time of service in the Vietnam War. And he made clear that he held McCain, alongside other American political leaders, responsible for the murder of Muammar Gaddafi, once asking whether McCain was unable “to live without such horrible and disgusting sights as the butchering of Gaddafi”. It is clear that Putin, like many of McCain’s critics who accused him of being a perpetual warmonger, hold him jointly culpable for the millions of deaths that have flowed from American backed military interventions.

Indeed, when during his 2015 UN speech, Putin criticised “policies based on self-conceit and belief in one’s exceptionality”, he might have had McCain in mind. Far from pushing the frontiers of liberty and order, the wars that McCain supported in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Syria were marked by failure. As Putin put it,

“Rather than bringing about reforms, an aggressive foreign interference has resulted in a brazen destruction of national institutions and the lifestyle itself. Instead of the triumph of democracy and progress, we got violence, poverty and social disaster. Nobody cares a bit about human rights, including the right to life.”

While Putin would concede to ‘liking’ McCain “to a certain extent..because of his patriotism…and…his consistency in fighting for the interests of his own country”, McCain never put on record any qualities that he felt Putin possessed. He died taking his anti-Putin animus to the grave. First he arranged for a Russian dissident named Vladimir Kara-Murza to serve as one of the dignitaries to carry his coffin to the front of the Washington National Cathedral at a memorial service. Then in another parting shot at his nemesis, McCain specifically requested for Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko and NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg to be seated beside each other during the ceremony.

These gestures were the last of what must surely rank as one of the bitterest international political rivalries of recent times.

*

This article was originally published on the author’s blog site: Adeyinka Makinde.

Adeyinka Makinde is a writer based in London, England. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.