Cover-Up at Guantánamo: “Torture” and “Suicide”. What Does the NCIS Have to Hide?

This is a story about the last few weeks in the life of a man who ended up in Guantanamo where the physical torture was bad enough, and the emotional torture was worse. He was put through the psychological equivalent of a wood chipper.

As they chipped away at his spirit, he chipped away at his own body, with clumsy suicide attempts that only succeeded in creating scars. One day, he really did kill himself – or so it would seem.

But what really happened to the 31-year-old Yemeni, Mohammed Al Hanashi? And why would anyone question the official version of what happened to him?

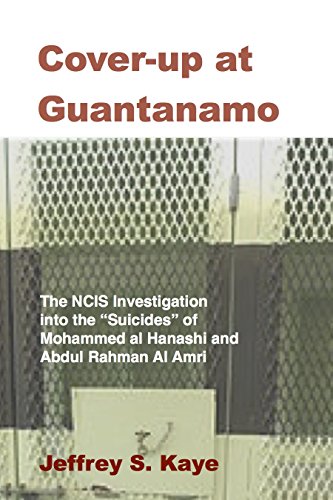

In his book — Cover-up at Guantánamo: The NCIS Investigation into the “Suicides” of Mohammed Al Hanashi and Abdul Rahman Al Amri — Dr. Jeffrey Kaye reveals what he found after relentless research. Clear evidence of a cover-up: missing, suppressed material, contradictory testimony, and more. As he wrote in his Preface,

“The possible criminality and compromised nature of the NCIS investigations is especially highlighted in the case of Al Hanashi, where NCIS was forced in the middle of its death query to open a subordinate investigation – reported for the first time here – into why the Guantanamo computerized detainee database system was ordered turned off as soon as Al Hanashi’s body was discovered. Even more suspicious, the order to shut off computer entries apparently was given by an unidentified NCIS agent him or herself!”

What Dr. Kaye had to work with was circumstantial evidence — which is defined as “evidence that proves a fact or event by inference.” This is the most difficult kind of material to work with, for it demands logic, perception, and imagination.

WhoWhatWhy Introduction written by Milicent Cranor

Excerpt from

Cover-up at Guantánamo: The NCIS Investigation into the “Suicides” of Mohammed Al Hanashi and Abdul Rahman Al Amri,

by Jeffrey Kaye

(Publisher: Jeffrey S. Kaye, PhD, September, 2016).

Chapter 4, “The only solution is death”: Al Hanashi’s Final Days.

On April 1, 2009, 31-year-old Mohammed Al Hanashi sat in his hospital cell at Guantánamo writing what reads like his last will and testament. The tiny room is nearly all white. There is a sink, a toilet, and a steel door with a slot for food and medications. A light shone at all times, day and night.

Probably unknown to Al Hanashi, in a grotesque coincidence, a USO tour of Guantánamo with both the 2008 winners of the Miss USA and Miss Universe contests had just visited the camp. Dayana Mendoza, the Miss Universe winner from Venezuela, caused some controversy with a blog piece about her visit.

“We visited the Detainees camps and we saw the jails, where they shower, how the [sic] recreate themselves with movies, classes of art, books. It was very interesting,” Ms. Mendoza wrote.

“The water in Guantánamo Bay is soooo beautiful! It was unbelievable, we were able to enjoy it for at least an hour. We went to the glass beach, and realized the name of it comes from the little pieces of broken glass from hundred of years ago. It is pretty to see all the colors shining with the sun….

“I didn’t want to leave, it was such a relaxing place, so calm and beautiful.”

How impossibly distant was the experience of detainee number 078.

“In the name of Allah the merciful the compassionate!” Al Hanashi wrote in Arabic. He had been imprisoned at that point for over seven years. Some may think, well, there are literally thousands of prisoners in US prisons who have been imprisoned as long and longer, who have spent years in isolation. Such prisoners often have been seriously damaged by their experience, but the Guantánamo experience took matters even farther.

The detainee had not been charged with any crime. He had not met with any attorney. The length of his imprisonment remained unknown and indeterminate. He was thousands of miles from home, held by a foreign power, manipulated in a regime that fancied itself a “battle lab in the war on terror.”

The detainee, Yemeni prisoner Mohammad Ahmed Abdullah Saleh Al Hanashi, was one of hundreds still imprisoned at the US Department of Defense “strategic interrogation” prison site at Guantánamo.

He’d been on hunger strike and fed via tube for some time (we don’t know if he was forcibly fed or not, but another detainee has written that he was). Now he pondered his death, probably by suicide. Or perhaps he thought he would die from the hunger strike, or as a victim of torture.

Al Hanashi pondered the “hardness” of life at Guantánamo. “Do not be sad for my death O family!” he wrote. “Allah almighty said ‘every soul will taste death.’”

“Life is no good without honor and a poet put it: ‘I have sworn either to live with honor and dignity or you may taste my bones.’”

From the document, it appears Al Hanashi had considered suicide deeply, and the deprivation of prison life at Guantanámo proved too much for him. “Anyway O family, I am well aware of my situation and of my circumstances,” he wrote. “I have not come to this without having been convinced by legal scholars.

“One has no blessing in life if one is deprived from certain joys.”

The cell of a non-compliant prisoner at Camp Delta, Naval Station Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Photo credit: US Department of Defense

According to his 2008 JTF-GTMO detainee assessment (one of hundreds released by Wikileaks), Al Hanashi was born in February 1978. He grew up in Yemen and graduated secondary school in 1995 or 1996. “After graduation… [he] worked for his father on the family farm where they raised livestock and grew watermelons, tomatoes, corn and other crops,” though the detainee assessment said he told a Yemeni delegation to Guantánamo that he used to be in the military.

In general, intelligence officials at Guantánamo thought Al Hanashi minimized his role fighting in forces associated with Al Qaeda. As a result, they judged him as “High risk,” a threat to the US and its interests and allies, as well as “A High threat from a detention perspective.” (They would state the same thing about Al Amri.)

According to Guantánamo expert Andy Worthington,

“[Al Hanashi] was one of around 50 prisoners at Guantánamo who had survived a massacre at Qala-i-Janghi, a fort in northern Afghanistan, at the end of November 2001, when, after the surrender of the city of Kunduz, several hundred foreign fighters surrendered to General Rashid Dostum, one of the leaders of the Northern Alliance, in the mistaken belief that they would be allowed to return home. Instead, they were imprisoned in Qala-i-Janghi, a nineteenth century mud fort in Mazar-e-Sharif, and when some of the men started an uprising against their captors, which led to the death of a CIA operative, US Special Forces, working with the Northern Alliance and British Special Forces, called in bombing raids to suppress the uprising, leading to hundreds of deaths. The survivors — who, for the most part, had not taken part in the fighting — took shelter in the basement of the fort, where they endured further bombing, and they emerged only after many more had died when the basement was set on fire and then flooded. “

This was the same prison revolt and subsequent massacre by US, British and Northern Alliance forces where the so-called “American Taliban,” John Walker Lindh, was also captured and later tortured by US operatives.

According to his Combatant Status Review Tribunal (CSRT) record, Al Hanashi went to Afghanistan to fight for the Taliban in early 2001. He was 23 years old.

Al Hanashi told Guantánamo officials he never heard about Al Qaeda until he read media reports while on the front lines in Afghanistan. He explained that he fought against the Northern Alliance, but said he never killed anybody.

After surviving Qala-i-Janghi, he was shipped off to Shabraghan Prison, where he spent the next four weeks or so recuperating in the prison hospital. Also in the hospital with Al Hanashi were victims of a transfer of Northern Alliance prisoners from Kunduz, the survivors of a purported war crime by Dostum’s forces (possibly with the knowledge or connivance of US Special Forces), as thousands of prisoners were “stuffed into closed metal shipping containers and given no food or water; many suffocated while being trucked to the prison. Other prisoners were killed when guards shot into the containers,” according to a New York Times story.

Did al Hanashi talk with survivors of the Dostum mass killings? Did he hear tales of US Special Operations soldiers or officers involved? According to his JTF-GTMO detainee assessment, an area of “possible exploitation” in his ongoing incarceration was the “Uprising at Mazar-e-Sharif and detainee’s reported leadership” there. The claims about “leadership” came from the interrogation of John Walker Lindh, who supposedly told interrogators that Al Hanashi had helped negotiate the surrender of prisoners at Qala-i-Janghi.

Appended to a section of the assessment is an “Analyst Note,” which stated, “If detainee was truly in a situation to negotiate for others, he may have been in a more significant leadership position than reported.”

The question of the level of leadership Al Hanashi exerted was brought up both by outside observers (like the former detainee Binyam Mohamed) and, as noted in the released NCIS interviews, by Guantánamo guard and medical personnel. In addition, as we have seen, when Guantánamo officials decided to change the policies for psychiatrically hospitalized detainees, bringing them into alignment with rules for the rest of the camp, top Guantánamo officials came to the Behavioral Health Unit to discuss the situation with Al Hanashi.

Some of the statements made about Al Hanashi can be taken with a grain of salt. Former Guantánamo inmate, Binyam Mohamed, who knew Al Hanashi, has said he didn’t believe the 31-year-old Yemeni force-fed hunger striker committed suicide. He told the journalist Naomi Wolf that reports that Al Hanashi was “an upbeat person with no mental problems and would never have considered suicide.” The documentary record from Guantánamo doesn’t support that conclusion.

According to a July 30, 2009 news report, “Mohamed refuses to believe that Saleh committed suicide and the US military refuses to say how he allegedly took his life. ‘He was patient and encouraged others to be the same,’ Binyam said.”

Mohamed also had a different tale about how Al Hanashi came to be in the Behavioral Health Unit. He told reporters, “I was asked if I wanted to represent the prisoners on camp issues such as hunger strikes and other contentious issues. I declined, as did most. But poor Wadhah [Al Hanashi] agreed, wanting to help his brothers the best he could. Little did he realize that if they didn’t get their way he would be the one sacrificed.”

Regardless of how accurate Binyam Mohamed’s narrative of events was, he certainly understood the prison’s environmental pressures, and he has held the US military accountable for Al Hanashi’s death, as suicide was so improbable under the conditions of detainee confinement. Mohamed pointed out that “Everything that someone could use to hurt himself has been removed from the cell, and a guard watches each prisoner 24 hours a day, in person and on videotape. In light of this, I am amazed that the US government has the audacity to describe Wadhah’s death categorically as an ‘apparent suicide.’”

Another odd coincidence surrounding Al Hanashi’s death concerns the transfer of Ahmed Khalfan Ghailani, a “high-value” detainee, who has been at Guantánamo since September 2006, to a New York federal court, only a week after Al Hanashi was found not breathing in Guantánamo’s psych ward. Ghailani was facing charges concerning his alleged role in the 1998 bombings of US embassies in Tanzania and Kenya.

The link between Ghailani and Al Hanashi is significant for at least one reason: According to Andy Worthington, Ghailani, who was tortured in the CIA’s black site prisons, fingered Al Hanashi in 2005 as having been at “the al-Farouq camp [the main training camp for Arabs, associated in the years before 9/11 with Osama bin Laden] in 1998-99 prior to moving on to the front lines in Kabul.”

But according to Al Hanashi and all other sources, Al Hanashi came to Afghanistan only in early 2001. Hence, his possible testimony at a trial in New York City, establishing that Ghailani’s admissions were false, and likely coerced by torture, may have been a hindrance to a government bent on convicting the supposed bomber. Interestingly, as Worthington points out, the other four embassy bombers were not kept in CIA black prisons or tortured, but convicted in a US court for the bombings in May 2001.

(Ghailani himself was acquitted of all but one of 280 counts in the embassy bombings, as the courts refused to admit a witness whose identification came via torture of Ghailani while he was held prisoner in a secret CIA prison. Even so, he was sentenced to life in prison for one count of conspiracy to destroy government buildings and property. Today, he is imprisoned at the ADX Supermax prison in Florence, Colorado.)

Al Hanashi’s death, coming only weeks before he was, after seven long years imprisonment, to meet finally with an attorney, brings to mind the untimely death of Ibn al-Sheikh al-Libi, also at first reported as a suicide, in a prison cell in Libya in May 2009, only weeks before Al Hanashi died. Al-Libi, too, was supposed to meet soon with people from the outside, according to a report from Newsweek.

Al-Libi was infamously the source of tortured information that Iraq’s Saddam Hussein was gathering weapons of mass destruction, information that Al-Libi later recanted. According to Human Rights Watch, some of their workers met Al-Libi in his prison cell on April 27, 2009, “during a research mission to Libya.” Al-Libi “refused to be interviewed, and would say nothing more than: ‘Where were you when I was being tortured in American jails”?

Jeffrey Kaye, author of Cover-up at Guantanamo: The NCIS Investigation into the “Suicides” of Mohammed Al Hanashi and Abdul Rahman Al Amri.

Photo credit: Jeffrey Kaye (Twitter) and Jeffrey S. Kaye, Ph.D publisher

As is the case with Al-Libi, the Al Hanashi death has a strange feel to it.

On June 1, 2009, three months after writing out his last testament, Al Hanashi was found seemingly lifeless in his cell. He was taken to the prison hospital, where he was pronounced dead less than an hour later by Dr. Enterprise, a prison physician. (Could that be his actual name? Medical officers routinely used pseudonyms at Guantánamo.) Military authorities said Al Hanashi had committed suicide by self-strangulation.

According to NCIS documents, Al Hanashi repeatedly told the Chief of Guantánamo’s Behavioral Health Unit (BHU) that he felt he was being tortured. They argued about it even on the last day of the detainee’s life.

Later that day, only a little over 2 months after writing what NCIS investigators labeled Al Hanashi’s “last will and testament,” Al Hanashi wrote what appeared to be a suicide note, but he was too depressed and disheartened to even finish it. Reportedly in silence and quickly, he strangled himself to death with a piece of elastic supposedly taken from his underwear.

Al Hanashi was haunted by the deaths of three prisoners, supposedly by suicide, on June 10, 2006. While there is evidence that the government’s story about those suicides has real holes — as already noted, former Guantánamo guard, Joe Hickman, wrote a book exposing the suppression of and tampering with evidence by the investigating agency — Al Hanashi told medical personnel in the Behavioral Health Unit at Guantánamo that he was supposed to die with the other three detainees on that day, too.

According to a statement given by the Senior Medical Officer, JTF GTMO, she had heard “at various JTF meetings” that Al Hanashi “was on a directed suicide list authored by [redacted].” But Al Hanashi was described as seeking refuge in the detainee mental hospital as a way to escape other detainees “who might have been pressuring him to commit suicide.”

No evidence of such a suicide list, or of pressures by other detainees on Al Hanashi to kill himself was included in the FOIA release I received in May 2015 on NCIS investigation into his death.

I had made the original FOIA request in January 2012. But little did I know at the time — which was two-and-a-half years after Al Hanashi died — that, as I filed my FOIA request, the NCIS investigation was still underway. Nor did I have any idea the investigation ultimately would take three years to complete.

Reading the documents that were finally released, it did not seem NCIS personnel felt much urgency about closing the case. At times, months went by and no investigative activity took place.

When the investigation was finally closed on June 13, 2012, NCIS had to admit in documented form that key portions of the evidence bearing on the chronology of events surrounding Al Hanashi’s death had gone missing.

As already described, someone — allegedly an investigator from NCIS itself — told Guantánamo personnel to stop entering information on Al Hanashi into a computer database, once his body was discovered. Subsequently, and we don’t know exactly when, the logs for the database the day Al Hanashi died and the following day disappeared entirely.

What happened during Al Hanashi’s final weeks? How did the detainee who had made numerous suicide attempts in the previous months leading up to his death, finally come to take his life? Did he, in fact, kill himself?

It is worth taking an in-depth, closer look at his death, including actions taken in the days leading up to his death by doctors, nurses and guards. But this remains a provisional narrative, as the full story is still pointedly unknown, blocked on one hand by government censorship and the failure to release all documentation. On the other hand, we do not have access to the scene of his death. We do not have access to the witnesses. They cannot be cross-examined. The key witness, Al Hanashi himself, is dead.

With all the attention of the world upon Guantánamo, the actual events inside the Cuba-based US prison are shrouded in deep mystery, sealed by classification and censorship. Hence the death of one man is barely known, much less remembered, and what happened to him even less known.

For the first time in this book, the circumstances around his death are open to public scrutiny. The record, even as it remains censored in part, shows that perceived violations of trust by doctors, nurses and mental health personnel contributed, at the very least, to Al Hanashi’s decision to take his life. It is possible some person or persons – medical personnel or guards – facilitated his death, or even murdered Al Hanashi. We can only speculate.

“Everything seemed normal”

Al Hanashi had been suffering from depression and suicidal thoughts for some time. A long-time hunger striker, Al Hanashi’s weight had fluctuated dramatically over the years, as detailed above. As a reminder, according to government records, on July 22, 2006 his weight dropped under 80 pounds. Only months before he had weighed just over 140. His weight had dropped by over 60 pounds in just four months.

According to his autopsy report, Al Hanashi had gone on hunger strike again in January 2009. During his last hunger strike, Al Hanashi was fed via tube. At his death, he weighed 120 lbs.

A Medical Record Review by NCIS investigators stated he entered the BHU on Jan. 10 for “making suicidal ideations.” His autopsy report also noted that Al Hanashi had made five suicide attempts in the month before he died.

The NCIS Medical Record Review contradicted that account, stating it was three attempts, all in the presence of prison personnel. By any account, Al Hanashi was deeply depressed and suicidal. Yet despite his history of recent suicide attempts, on the night he supposedly killed himself, Al Hanashi did not appear to be on suicide watch.

The guards reported little of consequence that evening. There were nine guards and a Watch Commander on duty that night, and seven detainees present on the BHU. One guard told NCIS investigators, “The BHU houses detainees that have expressed the desire to harm themselves.”

The procedure on the unit was to have two guards at a time monitor the seven detainees. One African-American guard with the Naval Expeditionary Guard Battalion (NEGB) described the scene:

“Our duties were to look inside each cell and check on the welfare of the detainees. We look inside the cell windows to ensure the detainees are not in possession of contraband or attempting to do harm to themselves. We usually spend approximately thirty seconds to one minute looking inside of each cell window.”

For whatever reason, this guard changed his statement later to reflect the fact that guards only spent “approximately thirty few seconds to one minute” watching the prisoner. The words “thirty” and “to one minute” were crossed out, though not enough that one couldn’t see what was originally written.

“Everything seemed normal,” the Navy guard stated. “I did not notice anything out of the ordinary.”

Al Hanashi was in cell two and “seemed in good spirits.” He had seen Al Hanashi upset in his cell before, pacing, or “praying loudly.” He was not writing anything, the guard said, “or doing anything out of his normal pattern.”

Another guard, who ended his roving tier patrol an hour before Al Hanashi died, told NCIS he too experienced the night as “normal.” On the other hand, he did see Al Hanashi writing something for most of the time he was on his shift.

In addition, Al Hanashi did not seem “in good spirits” to this guard, but rather seemed “down.” Al Hanashi was “a little more quiet than normal.” Al Hanashi reportedly was “usually talkative.” Nearly a full page of this guard’s statement is still redacted and “under classification review” by a Command other than NCIS.

An African-American Navy Airman assigned to the BHU Response Team told NCIS about earlier contact with Al Hanashi.

It was mid-May, only a few weeks before Al Hanashi’s death. He was told before his shift in mid-May 2009 that Al Hanashi had made a suicide attempt earlier that day. He’d rammed his head into a fence, and then tried to hang himself with his t-shirt.

The NCIS review of medical records dates the attempt to May 13, and expanded on the story. Al Hanashi reportedly “slammed his head on an exposed bolt located on a fence in the BHU recreational area.” The same day, he “attempted to strangle himself with a shirt.”

Five days before the May 13 attempt, Al Hanashi had also “tore off pieces of his shirt and attempted to strangle himself in the recreation yard.”

The guard told NCIS what he saw on his shift later that day after the suicidal behaviors, “Due to his suicide attempts, [redacted, but certainly 078, i.e., Al Hanashi] was under constant monitoring by a guard and he was placed in a green self harm suit. During the shift, [redacted, again, certainly 078] had some type of a Code Yellow (urgent medical issue) that required the response team to enter his cell and move him to the padded restraint chair adjacent to the tier.”

The medical issue isn’t known, but the guard thought, “[It] didn’t seem to be serious.” But another guard, in a different context, explained that Code Yellow means a detainee is “unresponsive.”

Another guard, who was on tier duty on the Duty Section One (Nights) shift the day Al Hanashi died, also described his duties. “Our job on the tier is to check every detainee every three minutes,” he told NCIS investigators. A check was only deemed satisfactory if they saw “breathing or some type of movement on each detainee.”

That night, this guard heard Al Hanashi talking from his cell with other prisoners on the BHU. This was not unusual, but as the conversations were in Arabic, he didn’t know what was said. There was nothing else unusual, either. Al Hanashi “seemed to be acting normal.”

“Is he breathing?”

Later that night, around 9:45 pm, Al Hanashi asked the guard to get him the nurse on duty. He called a corpsman, who then called the nurse. The guard observed the nurse talk with Al Hanashi for 5 or 10 minutes. She left and came back shortly with a sleeping pill (though the guard didn’t know what kind of pill it was at the time, he said). The guard watched him take it, swallowing it with water.

This guard heard Hanashi continue to talk to someone. The identity of the person he was speaking with is redacted in the documents, but from internal evidence, it seems to have been the nurse. The last reported contact with Al Hanashi, according to the autopsy narrative, was 10-15 minutes after Al Hanashi spoke to the nurse who gave him the pill. “… [H]e asked the guard to close the ‘bean hole cover,’ a sign that he was ready to go to sleep.”

Three minutes after his last check, “at approximately 2200,” he looked inside the cell and “did not see any movement or breathing.” Al Hanashi was described as lying “in the fetal position on the floor with the top of his head against the door and his feet facing the rear of his cell.” A green blanket covered his body up to his eyes. His hair, hands and feet were sticking out.

“I am not involved in [redacted, likely “078’s”] death,” the guard told NCIS, somewhat defensively it seems.

Yet another guard, a Caucasian male with NEGB, was coming on duty right at the time Al Hanashi was discovered on the floor of his cell. He overheard the two guards who were checking on Al Hanashi’s cell say “something to the effect, ‘is he breathing’ or ‘check to see if he is breathing.’”

This guard looked in the room and Al Hanashi wasn’t moving. He saw a woman, possibly a nurse, “dealing” with another detainee. She told the guard Al Hanashi might not be responding “because he had been given sleep medication by medical personnel.” At the same time, two other detainees “began shouting that [redacted] was sleeping and that we should leave him alone.”

The guard decided to ignore the warnings. He called in through a slot in the door to get Al Hanashi’s attention. Another guard reached in through the lower slot in the door and tried to shake Al Hanashi, who was lying close to the door. But then something caught the guard’s attention…

Jeffrey S. Kaye is a practicing psychologist in San Francisco, California. He is the author of numerous works, including “Isolation, Sensory Deprivation, and Sensory Overload: History, Research, and Interrogation Policy, from the 1950s to the Present Day,” Guild Practitioner, Vol. 66, No. 1, Spring 2009 and “CIA declassifies new portions of Cold War-era interrogation manual,” Muckrock, April 8, 2014.