Coronavirus in Gaza: Just 40 ICU Beds for Two Million People Under Siege

Israel should be told to lift the siege on Gaza or suffer the consequences of sanctions and isolation itself

Hospitals all over the western world are bracing for a tsunami of intensely ill patients suffering from breathing difficulties due to the Coronavirus.

In Britain, car companies are scrambling to produce ventilators. Plans are being laid for the army to build hospitals in conference centres. In Ontario, Canada, wards are being cleared, plans are being laid, models of infection are being scrutinised. If 70 percent of the population does not cut its social engagement by 70 percent, locking down will not work. Nerves are jangling.

Breaking point

So what do you think it is like in Gaza? This is not a question heard often these days, when Palestinians have been dropped off the international agenda, either as refugees or as people.

What do you think the prospect is for a besieged enclave that has 56 ventilators and 40 intensive care beds for a population of two million?

By comparison, according to figures from the OECD, Germany has 29.2 ICU beds per 100,000; Belgium 22; Italy 12.5; France 11.6, and the UK six and a half. Gaza has two.

Everywhere, medics are asking themselves whether they will be brought to their knees by Covid-19. They don’t ask themselves that question in Gaza. The health system there already is on its knees – by design. It passes for normality. It does not make the news. The international community scrambles with sticking plaster relief.

This has been the reality for the past 13 years. No conflict in that time was complete without a warning that the health system in Gaza was on the point of collapse.

In June 2018, at the start of a year when Israeli soldiers killed 195 Palestinians and injured nearly 29,000 people on the Great March of Return, UN experts said that healthcare in Gaza was “at breaking point”.

Acts of cruelty

During the war in 2014, hospitals such as Al-Aqsa in Deir al-Balah or al-Wafa in Shujaiyyeh were the target itself of Israeli shelling. Ambulances too were deliberately fired on by Israel. But this is what happens day in day out, acts of cruelty which never make the headlines that define who lives and who dies in Gaza.

Think about what happened to Muna Awad at the Erez Crossing in May last year. Muna had to hand over her gravely ill five-year old daughter Aisha to a woman she had never seen to get medical treatment in East Jerusalem. Aisha had been diagnosed with brain cancer, which could not be treated in the specialist hospital in Gaza.

Neither Muna nor her husband Wissam was allowed to travel with their daughter. Even Aisha’s grandmother, who was 75 (Israel refuses entrance to women under the age of 45 and men under 55), was refused entry.

Erez was the last time her mother saw Aisha conscious. The little girl had several operations in East Jerusalem but returned in a coma and never came out of it. She died in Gaza. Her case is not unique.

Al Mezan Centre for Human Rights, in Gaza, documented 25,658 Palestinians who applied for permits to seek medical treatment outside the enclave in 2018. Of that number, Israeli authorities delayed processing or rejected outright 9,832 applications – some 38 percent of cases.

If you want to know what collective punishment feels like in Gaza, try getting sick.

Aerial photographs of a quarantine hospital that is being constructed in western Rafah, #Gaza to prevent the spread of #coronavirus in the besieged heavy-populated enclave. pic.twitter.com/5m7Z3FotLs

— Palestine Live (@pallive_en) March 24, 2020

To retrieve the body of one of its soldiers, Hadar Golden, who was killed in combat in 2014, Israel reduced the number of entry permits from Gaza. The campaign was led by Golden’s family. There was an op-ed article in the Washington Post. And the government acted on it.

Figures supplied to Haaretz by Israel’s Coordinator of Government Activities in the Territories showed that in the first half of 2018, Israelrefused permission to 769 Palestinians seeking to leave Gaza for Israel because they were “first-degree relatives of a Hamas activist.”

So who holds the key to a medical collapse in Gaza? Israel.

Medical collapse

This is why the Ministry of Health in Gaza called on the international community to compel Israel to remove the blockade amid an acute shortage in ventilators, ICU beds, medicine and protective equipment.

And this is why the international community should now listen. Majdi Duhair, director of preventive medicine at the Ministry of Health in Gaza, told MEE that the biggest difficulty they faced was their ability to scale up ICU beds.

Given the shortage that exists, they only have 26 free ICU beds to deal with the spread of Covid-19.

“This is the biggest dilemma we face, all that is available is 65 beds of intensive care between children and adults, and this number is sufficient for normal and routine cases, and we need this number. There are six beds in the field hospital, and there are 18-20 beds in all places to deal with the spread of corona,” Duhair said.

He added:

“We are doing crew training, but this number is not sufficient. No new staff has been hired, the problem is there are volunteers, but the employment potential is limited, and existing employees receive 40-50 percent of their salaries.”

Gaza has suffered enough. No-one can just sit on the sidelines and watch this happen. Israel has to be told to lift the siege or suffer the consequences of sanctions and isolation itself.

This is an obscenity – one of many in the Middle East – that no western government can afford to maintain.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

David Hearst is the editor in chief of Middle East Eye. He left The Guardian as its chief foreign leader writer. In a career spanning 29 years, he covered the Brighton bomb, the miner’s strike, the loyalist backlash in the wake of the Anglo-Irish Agreement in Northern Ireland, the first conflicts in the breakup of the former Yugoslavia in Slovenia and Croatia, the end of the Soviet Union, Chechnya, and the bushfire wars that accompanied it. He charted Boris Yeltsin’s moral and physical decline and the conditions which created the rise of Putin. After Ireland, he was appointed Europe correspondent for Guardian Europe, then joined the Moscow bureau in 1992, before becoming bureau chief in 1994. He left Russia in 1997 to join the foreign desk, became European editor and then associate foreign editor. He joined The Guardian from The Scotsman, where he worked as education correspondent.

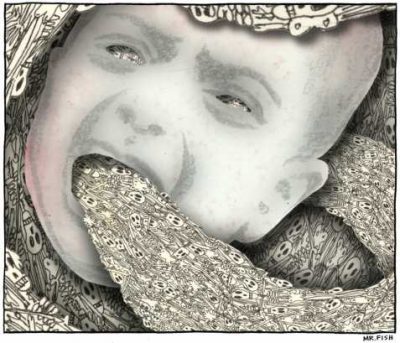

Featured image is from Desertpeace