COP26: US Military ‘One of the Biggest Polluters in the Middle East’

US military emissions are playing a significant and under-reported role in climate change, say activists

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @crg_globalresearch.

***

The Middle East has become one of the world’s most climate change-affected regions, with severe droughts, devastating wildfires, massive floods and pollution affecting millions of lives and making some areas nearly unliveable.

Greenhouse gas emissions – a major cause of global warming – have tripled globally over the past three decades, with the Middle East and North Africa region, which stretches from Morocco to Iran, warming by twice the global average, with a rise of four degrees Celsius.

But as world leaders meet at COP26, the United Nations Climate Conference in Glasgow, there is one source of emissions unlikely to face the scrutiny of discussion – states are not obliged to publicly disclose the emission levels of their militaries.

Researchers and climate advocates have argued that of particular concern is the US military, the planet’s largest institutional consumer of petroleum and, correspondingly, the single largest producer of greenhouse gases in the world, whose past two decades of waging wars in the Middle East have also left the world damaged by its greenhouse gas emissions.

“The US military emissions are the largest that I know of in the world. US military emissions, because it is the United States’ single largest energy consumer, are enormous,” Neta Crawford, co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University, told Middle East Eye.

“If the United States is really serious about leading the world on climate change and, in particular, the mitigation of emissions, then it needs to look at the military and military industry.”

Fuel consumption

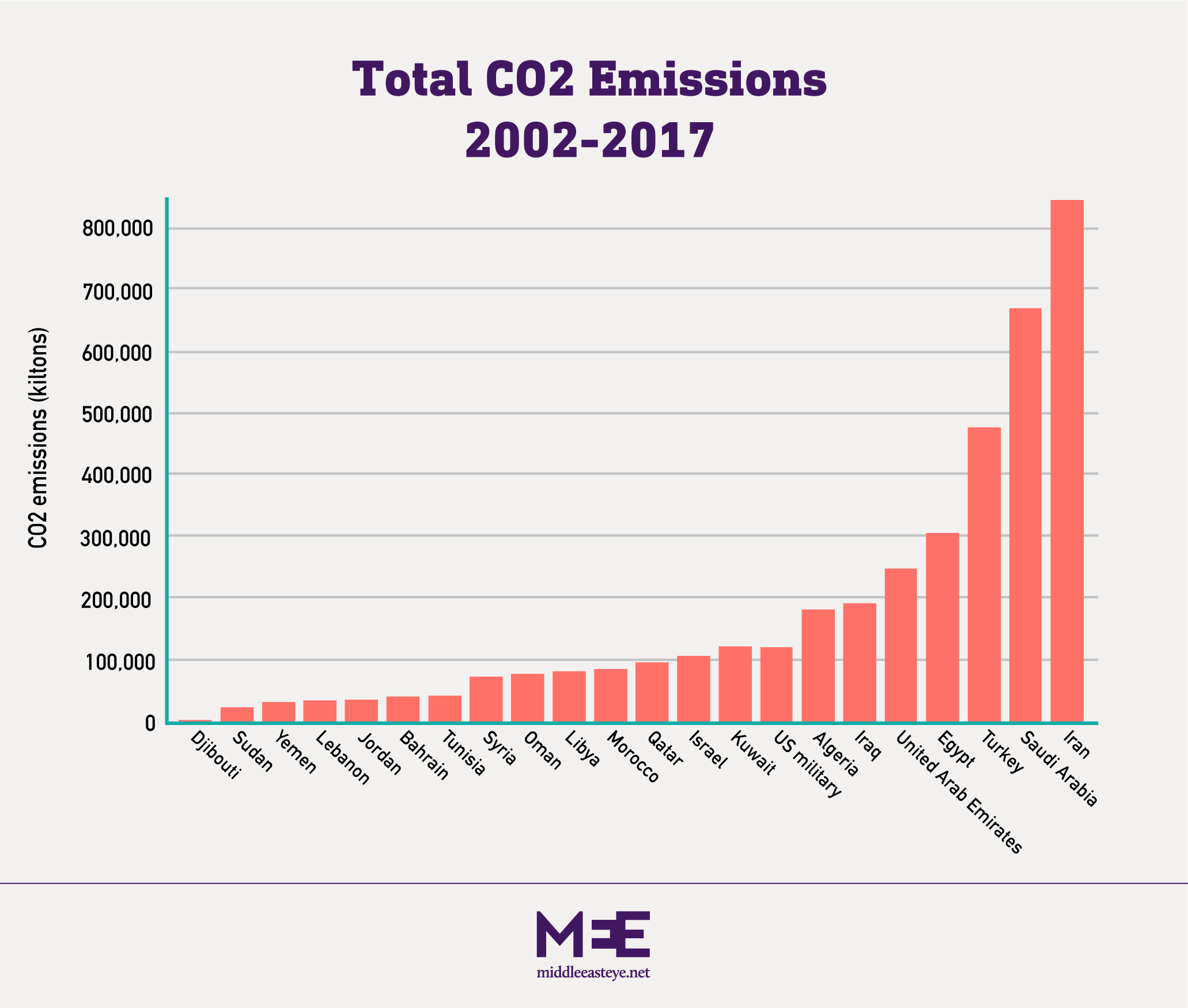

According to an estimate from the Cost of War Project, the US military produced around 1.2bn tonnes of CO2 emissions between 2001 and 2017, with 400 million of those tonnes directly accountable to the post-9/11 wars – in Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan and Syria.

Crawford noted that emissions from the US military were “larger than the emissions of entire countries in any one year; big countries with industry like Denmark, and Portugal”.

If the US military was a nation state in the Middle East, it would rank as the region’s eighth-largest emitter of greenhouse gases.

In 2017, the US military bought an average of 269,230 barrels of oil each day, burning a total of more than 25 million tonnes of CO2 that year, according to data obtained by researchers at Durham University and Lancaster University in the United Kingdom.

The most damaging source of US military emissions is the burning of jet fuel, which contributes between two and four times more to global warming than other types of fuel, because it is burned at higher altitudes.

Oliver Belcher, an associate professor at Durham University and one of the researchers, said “jet fuels are the highest pollutant in terms of hydrocarbons; they have the most detrimental effects on the atmosphere”.

Graph showing the total amount of emissions – reported by the World Bank – from Middle East countries, as well as the US military (MEE)

Military industrial complex

The consumption of fuel, however, only tells part of the story. The logistics of supplying the entire US military all over the world has an enormous carbon footprint “that’s probably been under-appreciated”, Belcher noted.

The agency that runs these operations, the Defence Logistics Agency Energy (DLA-E), oversees the delivery of fuel to more than 2,000 military posts, camps, and stations in 38 countries, as well as 230 locations where the US military has bunker contracts, which provide commercial ship propulsion fuels for military vessels worldwide.

“The supply chains that that agency runs also has a carbon footprint entailed in it because obviously moving material through any infrastructure is going to imply a carbon cost,” Belcher said.

However, “calculating military missions and accounting for them at all, is extremely difficult”, according to the researcher.

“Keeping track of how many vehicles have gone to and fro, for how long, how many times have they refilled fuel, all that basic everyday stuff that it takes to maintain operations in a military theatre, that’s very difficult to get numbers on, yet that’s the real nuts and bolts.”

Meanwhile, emissions from the manufacturing of weapons systems, munitions, and other equipment add another layer to the American military’s climate impact.

“Even though the [US military] emissions have declined, the military is still an enormously significant emitter. Because it bolsters and essentially pushes industry through its acquisition, research and development processes, it drives industrial emissions as well,” Crawford said.

The Cost of War Projected has estimated that the amount of CO2 emissions as a result of US military industry during the post-9/11 wars is roughly 153 million tonnes each year.

“In any one year, it is likely that the emissions of the DoD are about the same as military industrial emissions,” Crawford said.

Burn pits and other destabilising military actions

Beyond the US military’s contributions to greenhouse gas emissions and global warming, the Middle East’s climate and landscape has also been deeply affected by more direct actions, such as the burning of waste and training exercises.

At stations hosting US troops across the Middle East, the American military resorted to setting fire to their garbage as a means to get rid of it, releasing a myriad of toxic pollutants into the air for anyone around to breathe.

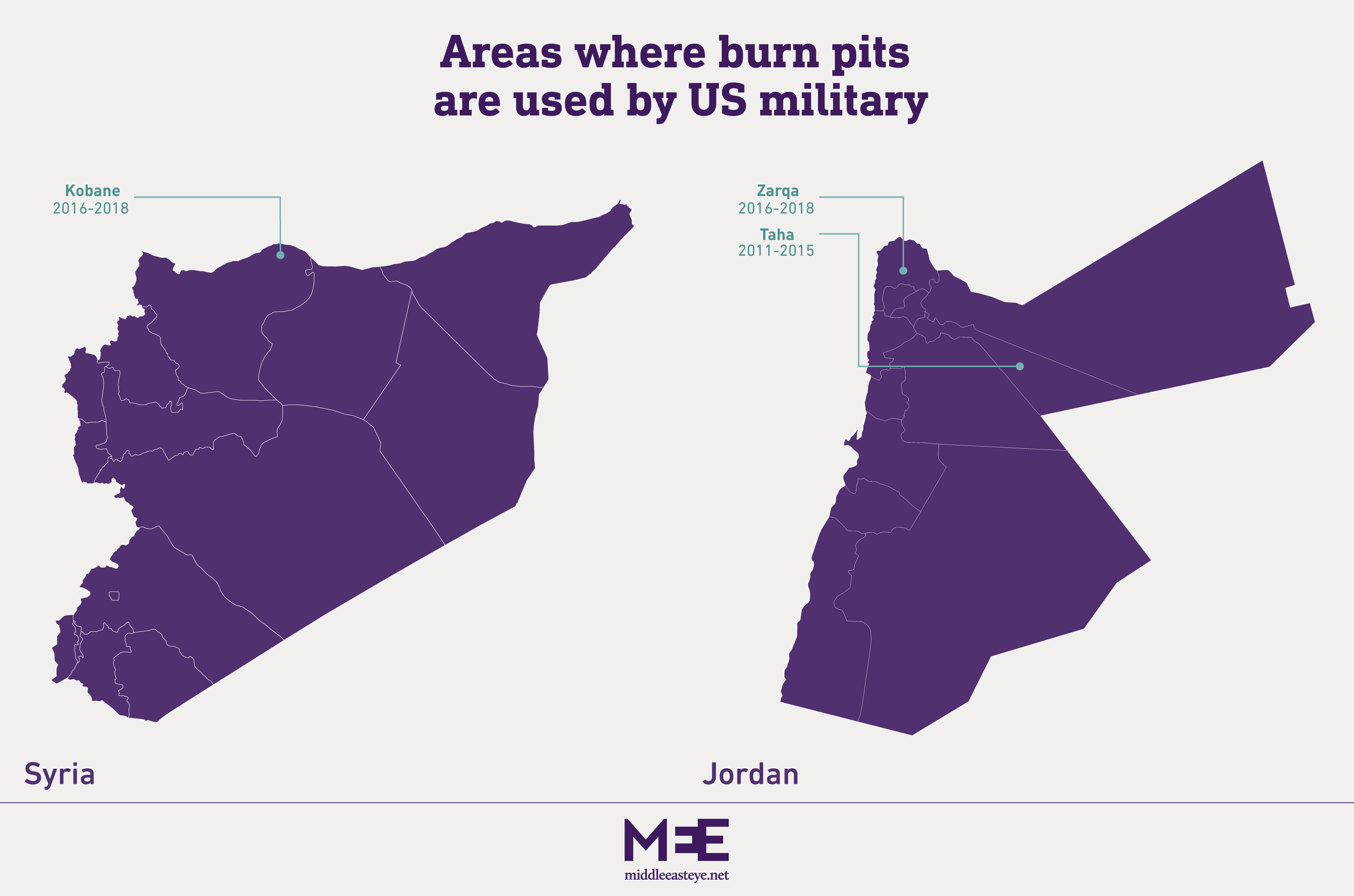

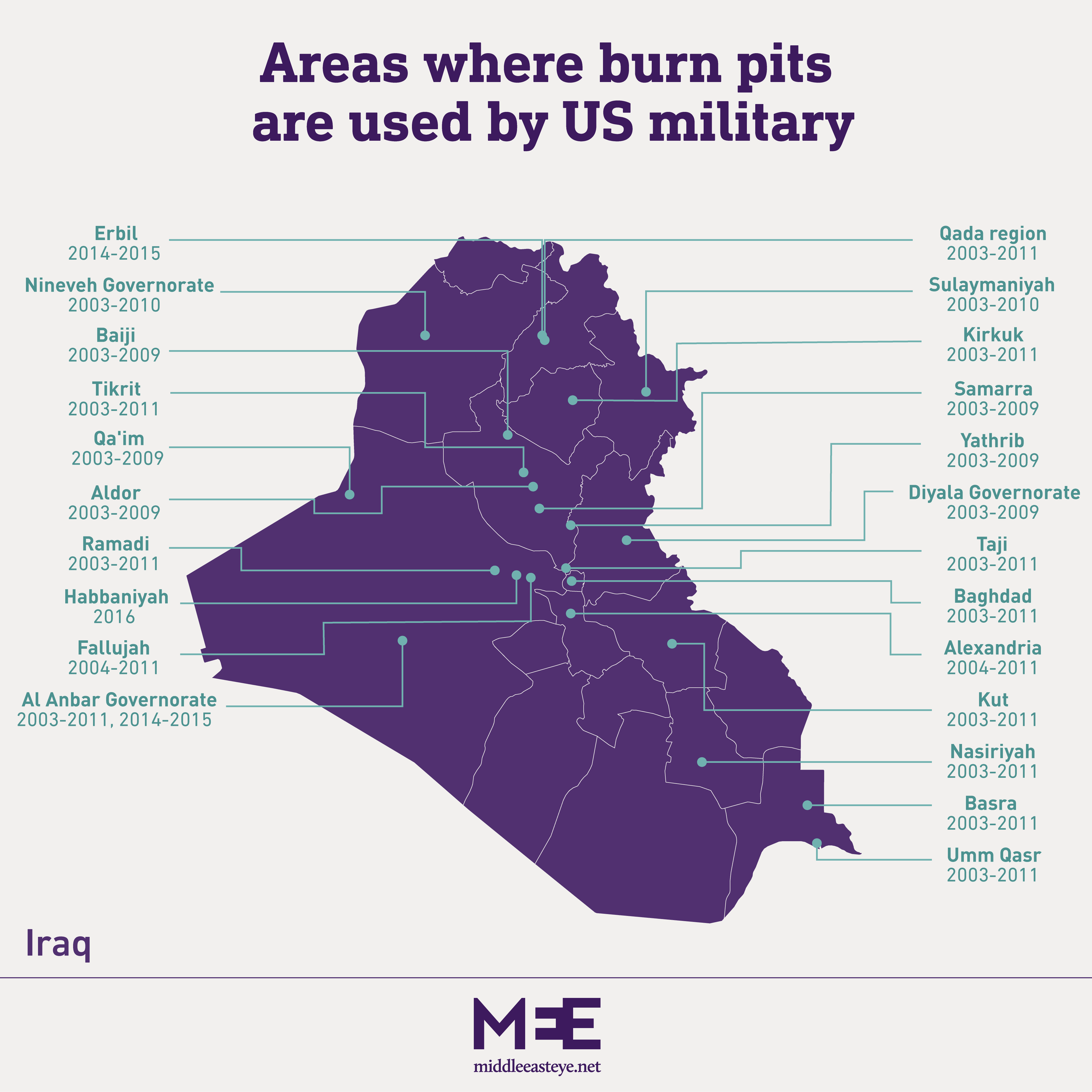

These burn pits were a common practice by the US military in Iraq, Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Bahrain, according to the Department of Veterans Affairs.

After throwing their waste – including chemicals, paint, medical and human waste, munitions, petroleum, plastics and Styrofoam – onto an open pit, jet fuel was poured onto it and set ablaze.

An assessment by the Pentagon found there were nearly 40 sites in which burn pits were used by the military, however some estimates from veterans’ groups put the number in the triple digits.

Numerous studies have shown that the pollution stemming from these burn pits have caused severe health complications for American veterans, and are likely to have affected civilians, contractors, and locals working on those military bases.

The burn pits were dubbed the new “Agent Orange”, referring to the chemical herbicide used by US soldiers in Vietnam and later proven to have caused cancers, birth defects and neurological problems among the Vietnamese people.

In an April 2019 memo to Congress, the Pentagon acknowledged that it still had nine active burn pits at bases throughout the Middle East and Afghanistan.

An assessment by the Pentagon found there a number of sites where burn pits were used in the Middle East (MEE)

According to the Pentagon, the majority of sites where burn pits were used were in Iraq (MEE)

In addition to pollution, US military activities, training exercises, and other operations that take place in the desert have helped contribute to dust storms that can travel across the region. There has been a subsequent increase in people’s overall risk of dying from dust exposure.

Barrak Alahmed, a PhD candidate in Population Health Sciences at Harvard University, told MEE that he and a team of researchers had seen a yearly increase in dust levels in the region surrounding Iraq between 2001 and 2017.

While he could not pinpoint US military operations as the direct result of these storms, he noted they definitely made the region more susceptible to them.

“Heavy military vehicles and explosions destabilise and disintegrate the desert soil making it easier to blowout and create dust storms that can travel long distances affecting many other Middle Eastern countries,” Alahmed said.

“We have done a number of studies in Kuwait – one of the most affected countries by dust storms. We found that dust days increase the overall risk of dying, and more specifically we found that migrant workers were most vulnerable to dust exposure.”

A need for accountability

In 1997, the international community came together to address the climate crisis and signed the Kyoto Protocol, which mandated that 37 industrialised nations and the European Union cut their greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet the US, which never ratified the agreement, requested an exemption on revealing its military emissions on the grounds of protecting national security.

Then in 2015, the Paris Climate accord was adopted, which included a measure in which countries could voluntarily report on military emissions.

However, there has yet to be any incentive or requirement for nations to do so, and the issue of military emissions remains absent from the COP26 agenda.

The only way to truly reduce these emissions, climate researchers argue, is to force countries, especially the US, to report on their military’s carbon emissions and work to reduce them.

On 9 November, advocates will launch a new website, dedicated to reporting on these emissions and allowing the public to see what is often left out of climate discussions.

“There needs to be some sort of accounting mechanism innovated within the military to account for these submissions,” Belcher said. “And this is one area where pressure should be applied.”

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @crg_globalresearch. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Featured image: In 2017, the US military bought an average of 269,230 barrels of oil each day, burning a total of more than 25 million tonnes of CO2 that year (MEE)