‘Collateral Murder’ and the My Lai Massacre

Comparing the reaction to the evidence of two war crimes reveals how much the United States has changed in the past 50 years, writes Joe Lauria.

To gauge the transformation in the response by the U.S. military, the mainstream media and the public to a U.S. war crime, one need only compare the reactions to two of the most heinous American crimes: the 1968 My Lai massacre in Vietnam and the gunning down of innocent Iraqis on a Baghdad street in 2007.

The latter was captured on a cockpit video from attacking Apache helicopters and revealed in a video released by WikiLeaks ten years ago today. Wikileaks obtained the video from a conscientious U.S. Army intelligence analyst, Chelsea Manning.

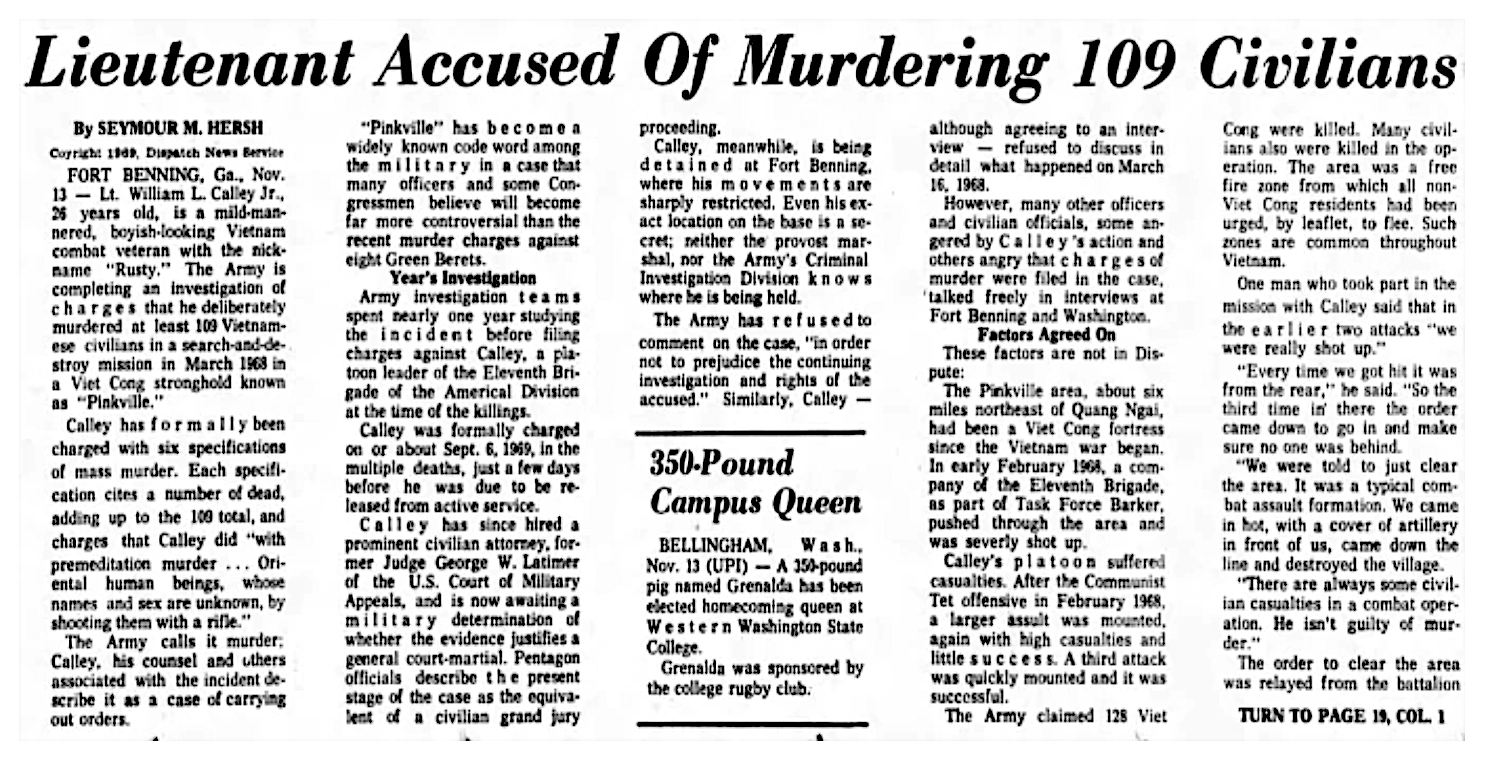

The My Lai incident was revealed to the public in Nov. 1969 through the reporting of investigative journalist Seymour Hersh. An army veteran whistleblower, Ronald Ridenhour, had first written in early 1969 to the White House, the Pentagon, the State Department and members of Congress revealing credible details about the massacre. It lead to a military investigation.

The probe found that U.S. Army soldiers had killed 504 unarmed people on March 16, 1968 in the village of My Lai, including men, women and children. Some women were gang-raped by the soldiers. The military investigation led to charges against 26 soldiers. Just one, Lieutenant William Calley Jr., a C Company platoon leader, was convicted. He was found guilty of the premeditated murder of 109 villagers. (Given a life sentence, he ultimately served only three and a half years under house arrest.).

But Calley’s conviction was largely covered up by the military. The New York Times ran only a short Associated Press story on Sept. 7, 1969, with few details. Hersh, however, heard something about the incident from a military source in Washington and started poking around. Eventually he got to see Calley in his cell in Georgia and was even allowed to look through classified notes on his case. Hersh had his story. He pitched it to Look and Life Magazines, but was turned down. Eventually the freelancer published his story at the obscure Dispatch News Service.

Hersh’s Dispatch News Service story picked up by the St. Louis Post Dispatch, Nov. 14, 1969.

There was a public outcry after Hersh’s revelation. It was picked up by newspapers across the nation, including on the front pages of The New York Times and Washington Post. It fueled anti-war sentiment and hatred of President Richard Nixon. Two days following Hersh’s story about 250,000 anti-war protestors gathered at the Washington Monument. “It surpassed in size the civil rights March on Washington in 1964 and was easily the largest — and was perhaps the youngest — antiwar crowd ever assembled in the United States,” the Post reported.

Forty years after the My Lai incident, Apache helicopter gunships patrolling the skies of Baghdad on July 12, 2007 opened fire on a group of civilians on a street below, killing a number of people, including two Reuters journalists, and the driver of a van who had come to pick up the wounded.

During the My Lai incident one brave American serviceman, Hugh Thompson, landed his helicopter between cowering civilians and advancing GIs and told the Americans his gunship would fire on themif they didn’t stop. In Baghdad, one U.S. soldier, Ethan McCord, saved the lives of two Iraqi children over the orders of his superiors.

Where the Similarities End

Some similarities between the two incidents are uncanny. But the outcomes were wholly different. Both were stories of a U.S. military massacre of innocent civilians, just two instances of many such massacres across Vietnam and Iraq. Both began with a whistleblower, Ridenhour on My Lai and Manning on Baghdad. Both stories were turned down by major media, and later accepted by obscure publications (which then made WikiLeaks well-known). (Manning was first turned down by the Timesand The Washington Post).

But that’s where the similarities end. The My Lai story led to a military investigation and a conviction of a U.S. soldier for mass murder. It caused a global outcry when all the facts became known. It contributed to the growing anti-war movement in the U.S. And it catapulted Hersh into prominence. As a result of his story, the freelancer was hired by The New York Times.

The Baghdad massacre led to no military investigation or charges against any soldier involved, despite video evidence that was stronger than what came out of My Lai. (The Army photographer who took the photo up top admitted to destroying pictures of the murders being committed.) The whistleblower was not jailed, as Manning was, but was listened to, and it led to an investigation. The ‘Collateral Murder’ video caused a stir, but hardly a global outcry, and it did not contribute to a U.S. anti-war movement. While WikiLeaks was catapulted into prominence, its publisher did not win a Pulitzer Prize, as Hersh did, but instead is languishing in a London prison on remand pending an extradition request by the United States to stand trial for espionage.

It bears repeating: At least one American soldier was imprisoned in My Lai. Hersh and the whistleblower did not go to jail. Not one U.S. soldier has gone to jail for the Baghdad massacre and the whistleblower and the journalist who revealed the crime were both imprisoned.

Manning’s 35-year sentence was commuted in 2017. She was again imprisoned for more than 250 days for refusing to testify to a grand jury against Assange, before she was released last month. Assange remains in a maximum security prison for doing the same job Hersh did.

These fundamentally different outcomes to a strikingly similar situation shows how far American society has sunk into the mire of authoritarianism and obedience.

Ellsberg and Assange

There is another Vietnam-era story that contrasts sharply with WikiLeaks, demonstrating how much the U.S. has changed for the worse in half a century. During the 1973 trial of whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg for leaking the Pentagon Papers it became known that the government had broken into Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office and bugged his phone to dig up dirt on him. The judge in the case was also offered the FBI directorship if Ellsberg were convicted.

When this serious prosecutorial misconduct became known, Ellsberg’s case was immediately thrown out and he was a free man. Fast forward nearly 50 years to Assange’s case. It is now publicly known that a Spanish company, UC Global, was contracted by the Ecuadorian government to conduct 24/7 video surveillance of Assange in the London embassy and that this audio and video–including of privileged conversations between Assange and his lawyers–was sold to the Central Intelligence Agency.

In other words, the prosecuting government eavesdropped on the defense preparations. This is even more egregious misconduct than in Ellsberg’s case, though it has not led to the extradition request on espionage charges being immediately tossed out.

At a rally for Assange in London in February I asked Yanis Varoufakis, the former Greek finance minister, why this was so. “The difference is that Dan was tried in a normal court,” he said. “Julian will never be given this opportunity. Julian is going to disappear into a system where not even his lawyers will know what the charges are. Habeas Corpus does not exist for him. Things are getting worse. Far worse.”

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Joe Lauria is editor-in-chief of Consortium News and a former correspondent for The Wall Street Journal, Boston Globe, Sunday Times of London and numerous other newspapers. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter @unjoe

Featured image: Photo by United States Army photographer Ronald L. Haeberle on March 16, 1968 in the aftermath of the My Lai massacre. (Wikipedia)