Impacts of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). Ease or Exacerbate China-India Rivalry?

The eventual completion of the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC) will either ease or exacerbate the Sino-Indo economic rivalry of the past few years depending on how New Delhi responds to Beijing’s latest trans-regional integration initiative, but whatever it decides to do, it’s clear that CMEC is destined to be a real game-changer one way or the other.

President Xi’s visit to Myanmar last weekend was marked by the clinching of 33 agreements that are in one way or another connected with the China-Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC). This latest trans-regional integration project of China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) aims to pioneer a CPEC-like connectivity corridor to the Afro-Asian (“Indian”) Ocean that would complement its predecessor in the northwestern corner of this body of water by further strengthening Beijing’s economic influence in South Asia. Beijing’s intentions are benign because its grand strategic goal is simply to ensure its reliable non-Malacca access to the Afro-Asian Ocean through which a sizeable percentage of its foreign trade traverses, but its moves have been interpreted by New Delhi (with a wink and a nod from Washington) as part of a plot to “encircle” it.

This state of affairs lays the basis for their “strategic dilemma” with one another that has contributed to their economic rivalry over the past few years, which dramatically reached a new height after India refused to sign on to the Chinese-led Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) at the very last minute during last November’s summit in Bangkok. At the same time, however, India has been playing a double game that it deceptively describes as “multi-alignment” by attempting to re-enter into economic talks with the People’s Republic as part of its so-called “balancing” strategy of supposedly pursuing equidistant relations with the world’s premier Great Powers. The signing of “phase one” of a more comprehensive US-Chinese trade deal, however, put India in a tough spot entirely of its own making which will shape its reaction to CMEC.

Not only didIndia fail to take advantage of the so-called “trade war” to position itself as a leading destination for Western companies re-offshoring from China like Vietnam did, but it now has to contend with China’s gradual economic reforms which will by default make the People’s Republic even attractive to Western companies in the long run especially since many of them already have an impressive footprint in the country. India also didn’t agree to a free trade deal with the US after the RCEP fiasco since it considered America’s demanded terms to be lopsided (though a deal might nevertheless soon be signed), but after “phase one”, Washington has no reason to “compromise” all that much since it already reached an important deal with Beijing. At the same time, the expansion of Chinese economic influence into South Asia continues apace with CMEC.

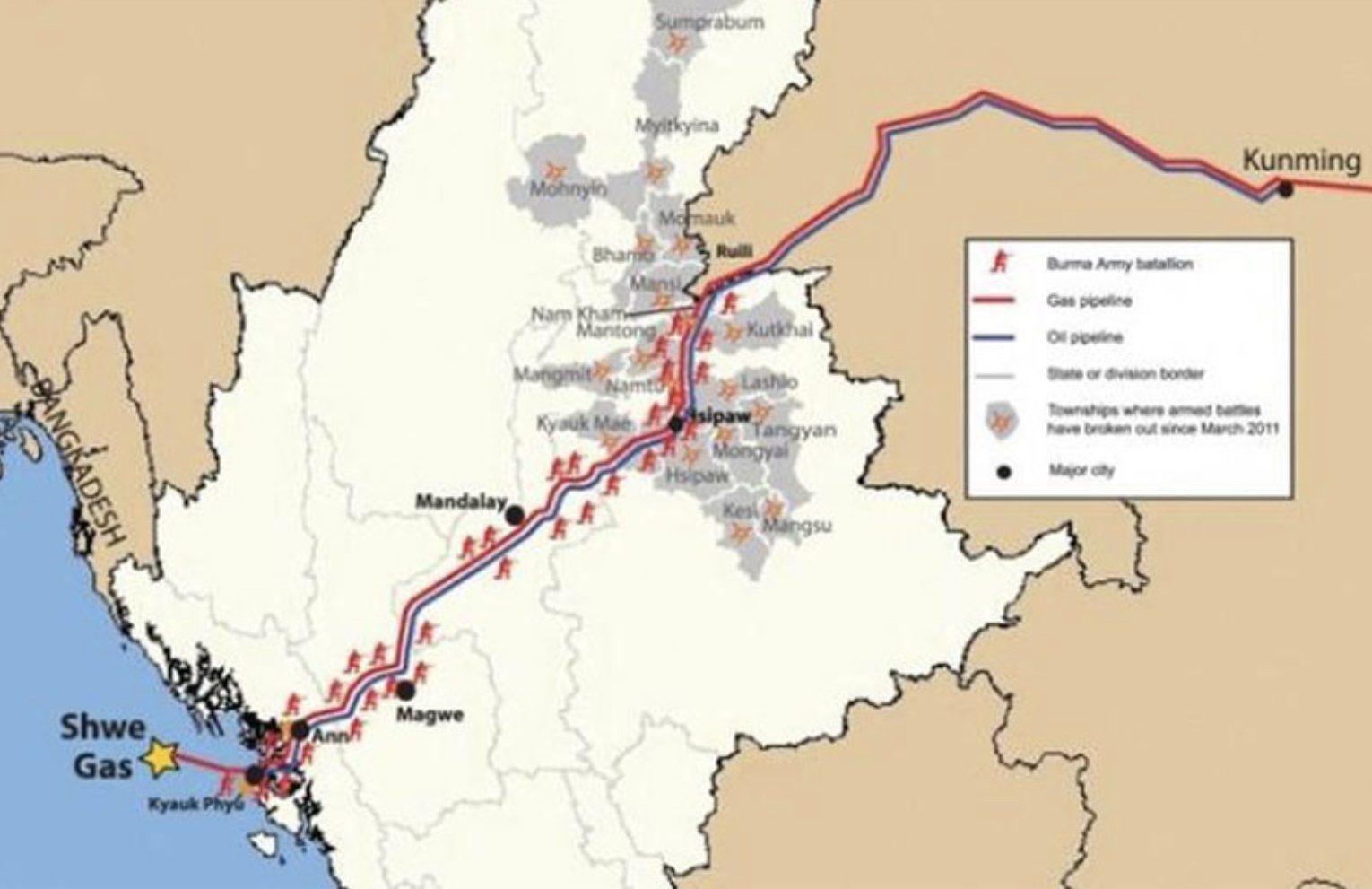

India also has strategic economic interests in Myanmar as well, namely in the country functioning as a transit state for New Delhi’s overland trade with ASEAN through the Trilateral Highway that will connect it with Thailand. CMEC and the Trilateral Highway are perpendicular to one another and both intersect in the centrally positioned city of Mandalay, so these connectivity initiatives can either complement one another or compete depending on whatever New Delhi decides. On the one hand, India might use Myanmar as a backdoor to China via RCEP, but on the other, China doing the same to India via the latter’s free trade agreement with ASEAN might defeat the entire purpose of New Delhi declining to join RCEP in the first place. In other words, Mynamar’s “economic multi-alignment’ between China and India makes both scenarios possible.

This naturally leads to the conclusion that India’s trade ties with Myanmar and ASEAN more broadly after their incorporation into the Chinese-led RCEP is the main issue which will have to be settled by New Delhi sooner than later. India has made spent a lot of time promoting its so-called “Act East” policy of ASEAN engagement, but it can’t continue with it at the same scale as before because of RCEP and CMEC unless it either modifies its relations with the neighboring bloc or accepts that it and especially Myanmar will function as the bridge more closely connecting the Indian and Chinese economies. Therein lies the dilemma, however, since India wants to keep China at arm’s length out of fear that its “Make in India” program of domestic industrial development will be hamstrung by the predicted large-scale influx of cheap Chinese goods through RCEP and Myanmar.

There were serious protests in India in early November before it officially declined to join RCEP precisely over these fears, and considering the current political unrest that’s spread throughout the country in a more wider way than those previous purely economic protests, the ruling BJP might not want to risk further inciting the populace by being seen as supposedly “selling out” to China. Even so, the only way to avoid the eventuality of closer Sino-Indo trade ties via Myanmar is to publicly call for the reformatting of Indian-ASEAN relations, which would risk ruining the goodwill that it’s fostered with the bloc over the past decade and make it seem like the country is economically isolating itself. New Delhi’s development vision for its restive Northeastern States (“Indian Balkans“) also hinges on ASEAN connectivity, so a chain reaction of regional uncertainty might ensue.

As a result of these interconnected strategic calculations, it’s clear to see that CMEC will either ease or exacerbate the Sino-Indo economic rivalry. The consequences of New Delhi’s decision to follow the former scenario would be the country’s further integration into the Chinese-led economic order that’s emerging all throughout Asia whereas its choice to pursue the latter scenario would contribute to its growing isolation and potentially also spark further unrest in the “Indian Balkans” if the government fails to do good on its previous pledge of bringing development to this long-neglected region. Given the observable tendency of the Indian leadership to tacitly “contain” China in cooperation with the US, the odds are that it’ll opt for the second scenario unless something unexpectedly changes, which would only work out to America’s strategic benefit.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on OneWorld.

Andrew Korybko is an American Moscow-based political analyst specializing in the relationship between the US strategy in Afro-Eurasia, China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and Hybrid Warfare. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from OneWorld