Citigroup’s Dark Pools: Here’s Why the Public Doesn’t Trust Wall Street

In 2008, the sprawling global bank, Citigroup, created under the controversial repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act, blew itself up with toxic debt hidden in the dark in the Cayman Islands in an exotic framework called Structured Investment Vehicles or SIVs. The unwilling taxpayer was forced into servitude to bail out this hubris that had occurred at the hands of captured regulators, infusing $45 billion in equity, over $300 billion in asset guarantees, and $2.5 trillion in below-market loans.

At the time of its implosion, Citigroup had over 2,000 subsidiaries, affiliates or joint ventures, many of which operated in the dark in foreign locales.

Flash forward to today: in March, the Federal Reserve said Citigroup had flunked its stress test and the Fed prevented it from boosting its dividend. (The so-called stress test is how the Fed measures a mega bank’s ability to withstand a major economic upheaval.) In rejecting Citigroup’s capital plan for 2014, the Fed said that Citigroup

“reflected a number of deficiencies in its capital planning practices, including in some areas that had been previously identified by supervisors as requiring attention, but for which there was not sufficient improvement. Practices with specific deficiencies included Citigroup’s ability to project revenue and losses under a stressful scenario for material parts of the firm’s global operations.”

Most Americans, and, sadly, members of Congress, believe that Citigroup is the parent of all those branch banks holding FDIC-insured deposits across America and bearing that angelic red halo over the word “Citi.” But Citigroup is far more than that.

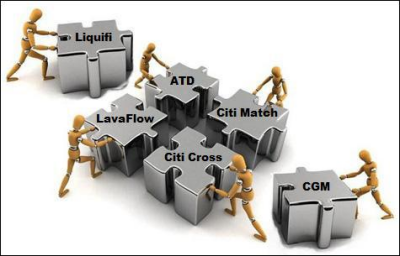

A recent record search by Wall Street On Parade suggests that Citigroup may be operating one of Wall Street’s largest collections of dark pools, trading stocks 24/7 around the globe in de facto unregulated stock exchanges which it operates under a dizzying array of different names.