China’s “One Belt, One Road” Initiative: “A New Silk Road linking Asia, Africa and Europe”

On Sunday May 14, China’s President Xi Jinping will inaugurate the One Belt One Road summit, the object of which is to to build a “new Silk Road linking Asia, Africa and Europe”, largely focussing on infrastructure investment. Global Research brings to the attention of its readers this carefully researched review by political scientist Zhao Bingxing

* * *

The debate on China’s ambitious “One Belt, One Road” (OBOR, also referred to as “Belt and Road”) initiative seems gradually cooled down in the last year and one plausible reason was the relatively slow and limited progress it made. But recent news released by Chinese government reheated it: The Belt and Road Forum for International Cooperation will be held in Beijing in the middle of this May and 28 heads of state and government leaders [including North Korea] have confirmed their attendance.

For international observers, at least two factors make this forthcoming meeting eye-catching. On the one hand, it may tell whether China can convince other countries it is capable of playing a leading role in promoting global free trade by implementing OBOR when the U.S. turns to isolationism and protectionism.

On the other hand, three and a half years have passed since this initiative was announced and a mid-term review is required, which should preferably in a summit or high-level forum, rather than by a one-sided progress report, and the conclusion of this review will be a focus. To make judgment on either of the issues, the analysis of the motive, rationale of OBOR are necessary but still not enough. We need to examine how successful this initiative was implemented in those relevant countries so far and what impact OBOR will bring to them. Considering the different national power, developing level, economic institution of these countries, and even their complicated relations with China, an unified or too generalized view without studying of each country should be avoided.

In this article, four countries in the OBOR scope, i.e. Russia, Uzbekistan, Malaysia and Germany are selected to do case studies and it shows that OBOR, though based on positive principles, which focus on enhancing connectivity, facilitating trade and improving infrastructure, may not bring equal benefit to the relevant countries along this route and its impact on these countries differs significantly from one to another. In the meantime, the response of these countries also differs, which is closely relates to their economic, geopolitical and ideological consideration.

Russia

According to Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road (hereafter referred to as Vision and Actions), the official guiding document of OBOR, one of the three routes of the “Belt” passes Russia and two passes Central Asia, whereby Russia considers it to be a part of its historical economic and regional interests.[1][2] Hence, Russia can be viewed as a key to the success of OBOR. In a sense, the construction of the “Belt” will face more challenges if it lacks Russia’s cooperation, or at least consent.

A recent official remark in respect to bilateral relations between Russia and China seems quite optimistic. On Jan 17 and 18, 2017, Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov and a Chinese spokesperson for the Ministry of Foreign Affairs respectively stated that Sino-Russian relations were “at their best level ever in the two countries’ history”.[3] Both of them also mentioned OBOR as a part of Sino-Russian cooperation.[4] Though China has consistently been seeking support and cooperation with Russia (and all the other countries along OBOR as well), it is important to note, however, that Russia’s position was not consistent and underwent an obvious shift.

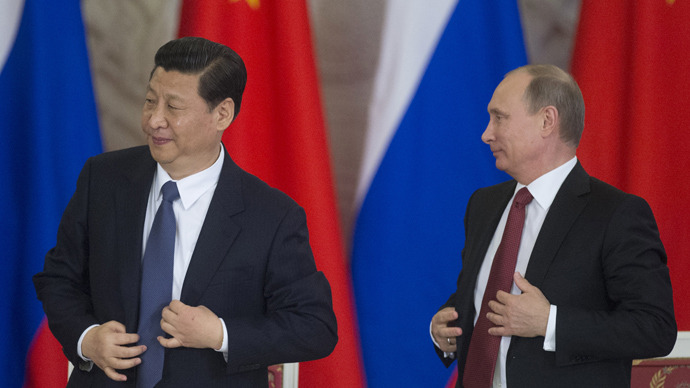

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin

Initially the Kremlin didn’t give the OBOR initiative positive feedback and it didn’t show enthusiasm for Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) in the first place, either, which reflected a dominant view of Russian elites that these would lead to a mutual distrust between the two countries.[5]

Russia’s concern about losing freight traffic was one reason for its unwillingness because the original route based on Chinese planning was to bypass Russia.[6] More importantly, it worried that the closer economic ties between China and the Central Asian countries would compete with Russia’s own integration plans for this region, which may further make the Central Asian countries drift away from Russia and embrace China.[7] But President Putin soon changed his position when China acknowledged Russia’s concerns and agreed to make some concessions to accommodate Russia’s needs, followed by the Russia’s endorsement of OBOR and its joint declaration with China on coordinating and linking OBOR to Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) in the middle of 2015.[8]

In fact, China did show considerable willingness and flexibility to cooperating and this was exemplified by China’s “creation” of an economic corridor with Russia and Mongolia, which would connect the “Belt” to Russia’s transcontinental railroad plan which was not in the initial plan of the OBOR.[9] Besides, China’s “Three Nos” principle in Central Asia, i.e. no interference with Central Asian countries’ internal affairs; no attempt to seek a dominant role in regional affairs; and no desire to create a sphere of influence, being a policy for dealing with its relations with Central Asian countries, to some extent eased Russia’s concern about China’s involvement in this region, because such showed that China had no intention of changing the status quo (Russia’s dominant influence) even though China didn’t formally acknowledge Central Asia as Russia’s backyard.[10] So far the concessions China made with regards to Russia are probably the most significant ones made during the promotion of OBOR because no other country alone constituted a reason for China to change the route.

Russia’s consideration is also based on the fact that some benefits, including infrastructure construction and cooperation on industrial capacity with China are not a priority and the only significant and substantial benefit to be incurred may be the receipt of funding from China. Rather, apart from the competing interest in Central Asia, some cooperation models as used in other countries such as contracting a construction project and dispatching thousands of Chinese workers there would hardly be acceptable for Russia due to its vigilance on the issue of Chinese migrants, especially in Far East region.

However, there are some reasons that Russia eventually decided to support this initiative. First, there is some tangible benefit that Russia can expect, though it doesn’t seem so imperative for Russia to seek out for the time being. In addition to being another channel for funding of infrastructure, OBOR, after an adjustment to its route as per Russia’s requirements, both in the plan and in practice, has brought some benefits to Russia.

Since Russia’s transcontinental rail was connected to OBOR and China-Mongolia-Russia economic corridor started to build, freight volume rocketed up in the railway routes from China to Russia, and to Europe via Russia, both of which used Russia’s transcontinental railroad, such as Chongqing-Inner Mongolia-Russia (Yu-Meng-E) and Hunan-Inner Mongolia-Europe (Xiang-Meng-Ou), which had positive effects for both China and Russia.[11]

Second, EEU is currently Russia’s priority. Though initially OBOR was viewed more as a rival, China’s clarification and commitment on connecting the two projects eased Russia’s concerns to a large extent. As a concrete step, a document was signed in the middle of 2016 in which the two governments decided to formally start negotiations on an economic partnership, mainly focusing on trade facilitation, merging different standards on intellectual property, customs, and other areas.[12] Third, it might not be wise nor feasible for Russia to contain China’s influence in Central Asia, or larger scope by boycotting this initiative.

For one thing, though the influence of Russia, the “elder brother” in Eurasia is still dominant, which is determined by its close political, economic, cultural, language and even people-to-people ties with the five republics in this region, the latter have long been seeking reducing their overdependence on Russia and striking a balance among big powers. Of course, Russia and China are the most important two in the region. In the past decade, China’s influence in the field of economics in this region grew very quickly and as such China has been able to compete with Russia, if not surpass it.

In 2015, all Central Asian countries have a larger share of their two-way trade with China than with Russia except for China’s exports to Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan and imports from Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan.[13] Besides, the build-up of mutual trust and cooperation in other areas such as that of anti-terrorism also increased China’s influence and say in this region. These facts make it very difficult for Russia to sway these countries by one-sided action. It is even interesting that Kazakhstan, where Xi Jinping first announced the “One Belt” initiative, is exactly the country which has the closest relations with Russia in Central Asia. For the other, OBOR is basically based on the actual needs of both China and many other countries. Also, China has enough political will and financial resources to push forward with. These factors mean that it can still proceed even if the support from some of the local big powers is absent.

In addition, it is necessary to examine Russia’s position beyond the calculation of the benefit or loss of OBOR per se and put it in a broader context. After the annexation of Crimea, the Ukrainian territory in March, 2014, the West imposed the harshest sanctions since the Cold War was over against Russia and this was a heavy, though not devastating blow to Russia, both in politics and in economy.

Data showed that Russia entered into a recession, with GDP growth of -2.2% for the first quarter of 2015, as compared to the first quarter of 2014, which was regarded as a success of Western sanctions in terms of the proximate goal of inflicting damage on the Russian economy.[14] Under this great pressure, it is no surprise that the Kremlin turned to the East and sought cooperation opportunities from China. Though China didn’t support Russia’s annexation of the Crimea and basically held a neutral position, it did have a great deal of interest in strengthening bilateral cooperation with Russia in economic, military and other areas because China also faced pressure from the West and needed political support from Russia. Admittedly, joining OBOR cannot bring enough benefits to Russia to offset its losses from the sanctions, nor can the closer relations with China.

However, a positive attitude to OBOR is vital for Russia if it hopes to get more financial support from China, whether under the OBOR initiative or other bilateral projects. It is hard to image that the $400 billion USD gas deal between the two countries, which was signed shortly after Russia annexed the Crimea and other cooperation projects can be implemented smoothly if Russia eventually declines this initiative that China attaches the most importance to.

On the whole, the benefit of OBOR seems more symbolic than substantial for Russia and thus Russia still sticks to the EEU project, which can help to bolster its economic and political dominance in Eurasia. This has been evidenced by the wording used when Lavrov mentioned that the Russia-China relations were at the best of all time this January. He emphasized “aligning” the two projects, instead of “joining” OBOR. Nevertheless, Russia still cannot neglect OBOR because the latter is closely related to China, who is able to provide key support to Russia. This support was vital to Russia when it suffered from the sanctions from the West and is expected to continue to play an important role in the near future because the relations between Russia and the West have been in a stalemate and chances of lifting the sanctions look very slim in the near future.

Uzbekistan

It is not a coincidence that Xi chose Central Asia to announced the “One Belt” initiative first. One plausible explanation for such is that this is the region where the ancient Silk Road first passed by when it left West China, but the underlying reason may be that the five republics of Central Asia are the countries who best match the ideas of OBOR and support it most as well. Since they gained independence twenty-five years ago, these landlocked countries had to face a common challenge, i.e. how to develop their economies in the Post-Soviet time?

Although Putin showed a strong desire to play an even bigger role in this region, Russia’s capabilities alone are not enough to ensure the prosperity of these counties. More importantly, such support is not without a price—overreliance on one big power will risk their independence. The rise of China provided an alternative to these countries which enabled them to choose partners from a wider range and benefit from both. OBOR is attractive to Central Asian countries because the focuses of this initiative, such as promoting connectivity, facilitating trade and investment, and improving infrastructure are all imperative to them. In this section, Uzbekistan is selected as an example, which can be a representative of the other four countries.

In May 2014, one year before the Vision and Actions was released, the then Uzbek President Karimov stated that Uzbekistan would actively participate in the building of the Silk Road economic belt when he met with Chinese President Xi.[15] In June 2015 China and Uzbekistan agreed to expand trade and economic cooperation under the framework of the “Belt initiatives”.[16] In June 2016, Karimov and Xi agreed to focus on jointly promoting this initiative.[17] All of which clearly shows Uzbekistan’s positive attitude to OBOR.

Uzbek President Karimov and Chinese President Xi Jinping

The main areas of cooperation under the OBOR framework include economic and trade cooperation, gas pipeline, railway tunnel construction, people-to-people exchange, etc. and much progress has been witnessed since a series of pacts were signed.[18] For example, the Qamchiq Tunnel in Uzbekistan, which is a part of the Angren-Pap railway line that connects Tashkent and Namangan, was completed on June 22, 2016 as a major achievement of OBOR.[19]

There is also some uncertainty about the implementation of OBOR in this country, which not only comes from the death of Karimov in last September, but also comes from local Uzbekistanis’ insufficient knowledge and recognition of OBOR, and too even China’s overall model of economic development.[20] In spite of this, cooperation related to OBOR still seems to be on track and there is no sign that it has been set aside by Uzbekistan.

Admittedly, the five republics in Central Asia differ from each other in terms of levels of democracy, natural resources, economic development levels, even in terms of domestic tensions or conflicts. Nevertheless, their common feature in geographic location cannot be overlooked. Being landlocked states, their trade connectivity with the rest of the world is limited, but they are also the overland juncture between East Asia and Europe, which gives them the potential to become a transportation hub that can connect the East and the West.[21] OBOR looks like a perfect solution to this situation.

If properly managed, it can better the connectivity within their individual country and that with other countries, which will bring triple benefits to them. First benefit is in meeting their local needs. Second is in facilitating their own export and import, and the third is to make profit by providing transshipment services. Also, appealing to Central Asian countries is China’s “no intervention in domestic politics”, “business-is-business” and economic oriented approach. When compared to Russia or other powers, China “is more inclined to perceive the local situation in terms of a sophisticated win-win scenario rather than in terms of aspirations of geopolitical dominance in the region” and such this policy has been approved to be successful.[22]

Overall, OBOR is beneficial to Uzbekistan and joining this initiative can be a reasonable choice. In fact, Uzbekistan can be a typical case with regards to OBOR from two different angles. One is that it represents the other four Central Asian countries which have similar geographic advantages as well as disadvantages and economic status quo. The other is that it can represent many medium or small developing states which have little direct conflicting interest with China in terms of geopolitics and thus can focus more on the economic cooperation they are mutually interested in. Basically, it is not difficult for them to find some areas in which they can cooperate with China on and benefit from them together.

Malaysia

Being an important part of 21st century Maritime Silk Road, or “One Road”, the other half of the OBOR, Malaysia, has its significance in two aspects. First, it is sitting on a strategic spot, in that Kuala Lumpur is quite close to the Malacca Strait, the second busiest waterway in the world. Trade statistics show that almost half of the world’s total annual seaborne cargo passed through this passage, which is jointly administered by Malaysia, Singapore and Indonesia.[23] Second, Malaysia is now China’s largest trading partner in ASEAN and the third largest in Asia and its policy option can be used as reference for some other countries.[24] In addition, Malaysia is able to help China expand markets in other ASEAN and neighboring countries.[25] All these factors together make Malaysia’s position key to the prospects of “One Road”.

In fact, Malaysia is perhaps the most active country regarding the OBOR in ASEAN, or Southeast Asia. In October 2014, Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak voiced his country’s readiness to support both OBOR and AIIB when meeting with Chinese State Councilor Yang Jiechi.[26] In addition, many other high-ranking governmental officials also echoed Najib’s position on OBOR. For example, Liow Tiong Lai, the Minister of Transport of Malaysia reiterated that the OBOR was a win-win project and indicated that Malaysia was ready for that in his speech at the Boao Forum for Asia in June 2015.[27]

Malaysian PM Najib Razak and Chinese President Xi Jinping

Several key areas and projects have been highlighted by both Malaysia and China under the umbrella of OBOR, including infrastructure, transportation, energy, property and even education and some progress have been made on each to date. For example, 60% of the equity of the 1MDB-owned Bandar Malaysia project in Kuala Lumpur was sold to a consortium led by a Malaysian company and China Railway Engineering Corp (CREC, a stated owned Chinese company) at RM7.41 billion in early 2016.[28] In November of the year, following an official visit to China by Najib, Malaysian and Chinese companies saw the signing of fourteen agreements on several iconic and mega agreements worth RM144 billion.[29] Another eye-catching project which China hopes to incorporate into OBOR is the High Speed Rail (HSR) connecting Malaysia and Singapore. Though the final result of HSR bidding will not be available until 2018, it is a general consensus that a Chinese-led consortium is one of the two most promising competitors (the other is Japanese-led consortium) because of its successful precedent as set in Indonesia.

There are several reasons that can explain the positive attitude of both government and business sectors. First, Malaysia has basically maintained friendly relations with China over the past few decades. In fact, Malaysia was the first country in Southeast Asia to build formal ties with China in 1974.[30] Such good relations are also based on the fact that there was little strategic conflict between the two countries after 1980s whereas there was also a frequent people-to-people exchange that occurred because of the large Chinese ethnic population present in Malaysia. It should be noted that territory disputes between the two countries do exist, which is about the waterways in the South China Sea. However, both Malaysia and China seem to be restrained about such and downplay this dispute, which is unlike the situation between the Philippines and China in the last several years. As a result, this dispute didn’t impede the bilateral relations. Second, both Malaysia and China have benefited a lot from previous economic cooperation and thus there is a strong driving force for them to maintain such development. A closer look at the bilateral economic cooperation between the two countries shows that two-way investment and trade involves different sectors, from manufacturing to construction, and different regions in these two countries, which reflects the in-depth and successful cooperation of both. Third, Malaysia believes that much of its needs in infrastructure, transportation and investment can be met by joining OBOR. As Najib notes, for instance,

“[The double-track East Coast Rail Line] will spur socio-economic growth in specific areas and bring great benefit to the people in the East Coast [of Malaysia]”.

Also, with the implementation of OBOR, Malaysia sees more opportunities to attract Chinese investment.[31]

OBOR can be a good opportunity for Malaysia too because it is more likely to succeed in this country than in some other developing countries along the OBOR. Aside from the strategic significance, Malaysia has a relatively stable political environment, well-established legal system and sound economic framework and good infrastructure. Its unique advantages include its large Muslim population as well as its Chinese ethnic population. The latter can help Chinese businesses easily enter into the local market and the former provide a possibility to connect the Chinese halal industry to the Muslim world.[32]

Though geopolitical consideration is not frequently and publicly emphasized when Malaysian high-ranking officials talk about OBOR, there is good reason to believe that Malaysia is trying to seek a balance between the two big powers of the United States and China. While actively getting involved in OBOR, Malaysia is also a member of TPP, a US-led trade agreement.[33] Since OBOR and TPP are widely considered to be part of a rivalry between China and the US, the involvement of both projects clearly shows that Malaysia hopes to benefit from both but not to overly rely on any. In a sense, the choice of “OBOR or TPP” reflects the choice of “US or China”, which is a common issue facing almost all the ASEAN countries, which is largely due to the geographic location of these countries. Although ASEAN countries try to speak with one voice, each of them have different responses to the “US or China” issue — some are more pro-American and others seem more pro-China. Of course, such is subject to change depending on their leadership and certain circumstances and the dispute over the South China Sea plays a key role in the policy option.

Last but not least, skepticism and concerns about OBOR can also be found in Malaysia. In addition to the dispute concerning the South China Sea, the “indifference” of Malay ethnic people as opposed to the “enthusiasm” of Chinese ethnic people and the exaggeration of the potential effect of OBOR are also challenges.[34] However, it seems that the Malay-Chinese cooperation on OBOR hasn’t been influenced much by such opinions.

Germany

China became the biggest trading partner of Germany in 2016 for the first time, overtaking France and the US, and Germany has long been China’s biggest trading partner in Europe.[35] This clearly shows the even closer economic relations between the two countries. From China’s perspective, Germany’s significance for OBOR primarily lies in its geographic location as one of the destinations of OBOR as well as its identity as an important actor among Western countries, which means that cooperation on OBOR, if successfully implemented, may set an example for other Western countries in Europe and attract more Western partners. Overall, the German government holds a relatively positive position towards OBOR and its focus is mainly on the areas of improving connectivity and trade and investment facilitation. Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel has welcomed the initiative to secure more Chinese investment in Europe.[36] At the same time, reservations and ambiguity can also be read from German government positions. German Consul General in Hong Kong when asked about the position of Germany on OBOR, said that Germany welcomed China’s openness to the rest of the world but he also highlighted that “any roads and any belts should be and will be in both directions”.[37]

German Chancellor Angela Merkel and Chinese President Xi Jinping

Although German government is not very willing to provide clear and strong support to OBOR, it didn’t refuse the relevant business opportunities that came with such. However, when compared to the Central Asian countries or some Southeast Asian countries, the result yielded in Germany under OBOR seems rather limited. The most prominent progress related to OBOR made in Germany is the Sino-European freight trains. In fact, the only five big projects to be undertaken by the end of 2016 were those linking the existing railroads. But it should be noted that several of them had been planned long before the announcement of OBOR and were just included in this initiative later.[38]

Unlike some countries which are China’s immediate rivals or have territory disputes with China, Germany can stay away from such tricky problems. As a result, the responses of Germany regarding OBOR, especially those positive ones, including the statements of the government or business sectors and projects discussed or agreed to are almost all based on economic calculations. In fact, the realistic or foreseeable benefits for Germany may also lie in this area. For one thing, the operation of Sino-German freight train provided a new option for the transportation of goods between China and Germany, and other European countries with a shorter timeline and more affordable cost. According to the China Railway, the total freight volume of the Sino-European railway reached 42 million tons in 2016, an increase of 12% and Germany was the main destination.[39] It should be noted that there are other destination countries of eastbound freight trains aside from China, such as Kazakhstan.[40] This demonstrates that the connectivity achieved can be beneficial to all the countries along OBOR. For the other, it did attract more Chinese investors to Germany. So far around seventy enterprises have settled in Duisburg, one of the destinations of Sino-German freight train, and most of them entered the European market within the last two years.[41] Overall trade and investment statistics show a very positive trend for the past three years and OBOR did play “some” positive role in such, though it may not be easy to measure precisely to what extent OBOR contributed to this trend.

Admittedly, the challenge facing OBOR in Germany is huge, and such a challenge is quite different from that in the developing countries or in China’s neighboring rivals. For a Westernized developed economy like Germany’s, infrastructure, one of the key pillars of OBOR, which is also a focus for many of the countries in Central Asia and Southeast Asia, is not a priority, nor even a concern of Germany’s because infrastructure is well-established throughout the country. Foreign investment is generally welcomed but not a pressing need. The cooperation on manufacturing capacity which has been in operation by China and some developing countries along OBOR is not applicable to Germany at all. This explains why the major benefit, if not the only benefit, that is attractive to Germany may be the connectivity created by OBOR and the resultant trade and investment opportunities.

In addition to the mismatch as mentioned, the obvious divergence between Germany and China regarding China’s markets, transfer of cutting-edge technology to Chinese companies, Chinese state-owned enterprises, or ultimately, China’s model of economic development is also a big obstacle for OBOR. For example, Berlin became seriously concerned that Chinese acquisition of hi-tech German companies would make China an even more aggressive competitor while Chinese officials criticized this new protectionist tendencies in Germany in response.[42] Needless to say, this is a common issue between almost all the EU countries and China. Furthermore, the EU’s approach has, to a large extent been based on a democratization and human right paradigm, which can be viewed as one of the root causes of their indifference and skepticism of OBOR.[43] As a result, Germany’s involvement with OBOR is limited and the influence of OBOR to this country is drastically weakened.

Siemens is a German conglomerate company with headquarter in Beijing, China.

For years Germany’s policy on China has been split between the economic interests and ideological considerations. On the one hand, it cannot ignore the Chinese markets and cooperation with China, which has brought huge benefit to its economy. On the other hand, Germany’s free market capitalism and values can hardly accommodate China’s development and expansion based on the Chinese model and thus deterrence is required. This dilemma has inevitably influenced how Germany looks at OBOR and what impact OBOR will bring to Germany. The result is, not surprisingly, a temporary balance between the two objectives. Of course, such a balance is not unchangeable and the struggle over economic interests and ideological principles will continue. A recent and noticeable event that occurred which may sway Germany’s position might be US president Trump and his isolationism. Before Merkel’s meeting with Trump, Merkel and Xi stressed a commitment to free trade during a telephone call.[44] This move signals that Germany may have to attach more importance to achieving economic cooperation with China, which means OBOR will probably have a more favorable environment in Germany in the future.

The case of Germany can reflect the general European situation to some degree and it basically coincides with European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker’s statement, who also emphasizes the importance of investment and links and holds that this initiative can bring huge benefit to both China and the EU, if it works well.[45] However, the representation of Germany shouldn’t be overestimated. On the one hand, there is no official EU position on OBOR as of yet and EU countries also lack a collective voice.[46] On the other hand, the Germany case is more applicable to Western Europe than Eastern, Central and Southeastern Europe. Unlike Germany, most countries in the Central, Eastern and Southeastern parts of Europe are less developed and thus need more infrastructure building assistance and foreign investments, which brings them more opportunities to cooperate with China under OBOR. And this has been evidenced by a series of cooperation between two parties, such as the China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO)’s purchase of the Greek port of Piraeus and China’s building of a high-speed railway from Hungary to Serbia.

Conclusion

The analysis of the four countries, though fragmented and not adequate to provide a whole picture of the impact of OBOR for those countries within the scope as well as their response, to some extent reveals the trend of the relations between OBOR and the relevant countries, because each of the four countries can represent a group of countries, or at least reflects some key consideration of the countries with the same features.

First, big powers are more inclined to put OBOR in the context of power rivalry and this inevitably reinforces OBOR as a challenge and usually leads to distrust of this initiative. Russia’s response initially reflected

this relationship but China’s immense move towards making concessions and Russia’s plight in the Ukraine eventually changed Russia’s position. By comparison, India is a case in point to show how another power is wary of China’s OBOR initiative. Since India positions China more as a rival than a partner, and there are no key drivers that emerged like those which occurred in Russia’s case that could reverse the trend, to date India hasn’t endorsed this initiative and there is little hope it will in the future. To some degree, the benefits or losses that OBOR can yield have become secondary to geopolitical considerations. Small or medium states, such as the Uzbekistan and Malaysia cases suggest, however, don’t want to get involved in the great power games and tend to focus on the tangible and immediate gains that can be derived from OBOR. They don’t seem to care whether or not China can get more from the bilateral cooperation than they do. In reality, many of them tend to seize the opportunity as it presents itself and transform it to improve their own country’s economy.

Second, developing countries are meant to benefit more from OBOR. Overall, the trade and investment facilitation, one of main goals of OBOR is universally welcomed by both developed countries and developing countries alike. But only the developing countries have huge demands for infrastructure building and requirements for relevant funding to be invested, which can probably be met by the implementation of OBOR. Then it should come as no surprise that developing countries along OBOR show relatively more positive attitudes towards it.

Third, political and economic institutions and too even ideology can play a important role in the assessment of OBOR as well as the position a country takes on it. Western counties are more concerned about the role of the Chinese government and state-owned enterprises in OBOR and are prone to link the implementation of this initiative outside China to the market environment within China. By contrast, non-Western countries have less concern in this regard partly because some of them are also practicing state capitalism, rather than free market capitalism. Therefore, their judgment is basically centered on what result OBOR can yield and to what degree such is beneficial to them.

In general, the idea of enhancing connectivity and promoting trade, which constitutes the main rationale of OBOR, is positive and this explains why OBOR won quite a bit of recognition after three years of intensive promotion, though it has always been accompanied by skepticism and challenges outside China. However, this initiative is still not a one-size-fits-all solution because its real effect relies heavily on the different situation of each country. Then it is no surprise that each country has different positions, all depending on the consideration of various factors, including economic, geopolitical, ideology, etc. Roughly speaking, OBOR is more of an opportunity for small and medium developing states than big powers or Western countries.

In a sense, Trump’s new policy, Brexit and even the rise of right-wing political force in West Europe provided an unexpected opportunity for China’s OBOR initiative because most countries in the world are still in favor of open and free trade. In the meantime, they also need some kind of mechanism and project to materialize this conception. Intentionally or unintentionally, OBOR may probably play a positive role in this regard, but we also need to realize its limit and avoid too optimistic or unrealistic expectation.

NOTES

[1]National Development and Reform Commission, Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.

[2]Linn, J. F., Central Asian Regional Integration and Cooperation: Reality or Mirage?, 96.

[3]See Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov’s remarks and answers to media questions at a news conference on the results of Russian diplomacy in 2016, Moscow, and

Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesperson Hua Chunying’s regular press conference on January 18, 2017.

[4]Ibid.

[5]Li, X., Silk Road Can Find Common Ground with Eurasian Economic Union.

[6]Wilson, The Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Silk Road: Implications for the Russian–Chinese Relationship, 119.

[7]Yu, China-Russia Relations: Putin’s Glory and Xi’s Dream.

[8]Wilson, The Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Silk Road: Implications for the Russian–Chinese Relationship, 119.

[9]Li, X., Silk Road Can Find Common Ground with Eurasian Economic Union.

[10]Yu, China-Russia Relations: Putin’s Glory and Xi’s Dream.

[11]Xinhua, China Uses Cooperation on Regional Ports to Boost China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor.

[12]Shtraks, China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative and the Sino-Russian Entente: An Interview with Alexander Gabuev.

[13]Central Intelligence Agency. World Factbook,

[14]Christie, Sanctions after Crimea: Have They Worked?

[15]Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC, Xi Jinping Meets with President Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan.

[16]Xinhua, China, Uzbekistan to Strengthen Cooperation Under the Silk Road Initiative.

[17]Xinhua, China, Uzbekistan Agree to Focus on Belt and Road Development.

[18]Xing, Guangcheng, and Weiwei Zhang, Promote the Building of Sino-Uzbeki “One Belt, One Road”.

[19]Xinhua, Chinese, Uzbek Leaders Hail Inauguration of Central Asia’s Longest Railway Tunnel.

[20]Chen, Julie Yu-Wen, and Olaf Günther, China’s Influence in Uzbekistan: Model Neighbor or Indifferent Partner?

[21]Li, Z. G., Central Asia Embraces “One Belt, One Road” Because of the Matched Interest.

[22]Kozłowski, The New Great Game Revised: Regional Security in Post-Soviet Central Asia.

[23]InvestKL, One Belt One Road: Kuala Lumpur is Sitting on a Strategic Spot.

[24]Foon, “Belt-road” to Benefit Businesses.

[25]Ibid.

[26]Xinhua, China, Malaysia Wow to Promote Bilateral Relationship.

[27]Liow, Speech By YB Dato’ Sri Liow Tiong Lai, Minister Of Transport, Malaysia, Boao Forum For Asia – Luncheon Speech One Belt One Road Strategy, Vision, Action Plan.

[28]Khoo, China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ Initiatives in Malaysia.

[29]Bizhive, Riding the dragon: Harnessing Malaysia-China’s Trade Partnership.

[30]Foon, “Belt-road” to Benefit Businesses.

[31]Bizhive, Riding the Dragon: Harnessing Malaysia-China’s Trade Partnership.

[32]Liow, Speech By YB Dato’ Sri Liow Tiong Lai, Minister Of Transport, Malaysia, Boao Forum For Asia – Luncheon Speech One Belt One Road Strategy, Vision, Action Plan.

[33]With the inauguration of President Trump, the US quitted TPP on Jan 23, 2017. See http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-38721056

[34]Chen, J.S., Where is “One Belt, One Road” Heading for?

[35]Xinhua, Sino-German Trade Reaches a New Level Based on Mutual Benefit.

[36]Gaspers, Germany Wants Europe to Help Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

[37]Lau, Make China’s Belt and Road Initiative a Two-way Street, Says German Consul General in Hong Kong.

[38]Ibid.

[39]Guan, “One Belt, One Road” Is a Lucky Key for Us.

[40]Ibid.

[41]Ibid.

[42]Larres, China and Germany: The Honeymoon Is Over.

[43]Arduino, China’s One Belt One Road: Has the European Union Missed The Train? 14.

[44]DW, Germany, China Stress Commitment to Free Trade Ahead of Merkel’s Meeting with Trump.

[45]Xinhua, Interview: Europe to Benefit from China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative: EC chief.

[46]European Parliament, One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s Regional Integration Initiative.

SOURCES

Arduino, Alessandro. “China’s One Belt One Road: Has the European Union Missed the Train?” Policy Report, Nanyang Technological University, Mar 2016

Bizhive, Yvonne Tuah. “Riding the Dragon: Harnessing Malaysia-China’s Trade Partnership.” Borneo Post Online, Nov 13, 2016

http://www.theborneopost.com/2016/11/13/riding-the-dragon-harnessing-malaysia-chinas-trade-partnership/

Central Intelligence Agency. World Factbook, CIA website

https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/wfbExt/region_cas.html

Chen, Jinsong. “Where is ‘One Belt, One Road’ Heading For?” (yi dai yi lu, lu zai he fang), Oriental Daily News, Sept 27, 2016

http://www.orientaldaily.com.my/columns/pl20153441#

Chen, Julie Yu-Wen, and Olaf Günther. “China’s Influence in Uzbekistan: Model Neighbor or Indifferent Partner?” The Jamestown Foundation Global Research & Analysis, Nov 11, 2016

http://www.silkroadreporters.com/2015/05/13/chinas-influence-grows-in-uzbekistan/

Christie, Edward Hunter. “Sanctions after Crimea: Have they Worked?” NATO Review

http://www.nato.int/docu/review/2015/Russia/sanctions-after-crimea-have-they-worked/EN/index.htm

DW. “Germany, China Stress Commitment to FreeTtrade Ahead of Merkel’s Meeting with Trump.” DW, Mar 16, 2017

http://www.dw.com/en/germany-china-stress-commitment-to-free-trade-ahead-of-merkels-meeting-with-trump/a-37973301

European Parliament. “One Belt, One Road (OBOR): China’s Regional Integration Initiative.” European Parliament Briefing, July (2016): 1-12

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPRS_BRI(2016)586608

Foon, Ho Wah. “’Belt-Road’ to Benefit Businesses.” The Star Online, Aug 2, 2015

http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2015/08/02/belt-road-to-benefit-businesses/

Gaspers, Jan. “Germany Wants Europe to Help Shape China’s Belt and Road Initiative.” The Diplomat, Dec 17, 2016

http://thediplomat.com/2016/12/germany-wants-europe-to-help-shape-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative/

Guan, Kejiang. “’One Belt, One Road’ is a Lucky Key for Us.” (yi dai yi lu shi wo men huo de de xing yun yao shi), People’s Daily, Jan 26, 2017

http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2017-01/26/nw.D110000renmrb20170126_4- 03.htm

InvestKL. “One Belt One Road: Kuala Lumpur is Sitting on a Strategic Spot.” InvestKL website, Oct 27, 2016

http://www.investkl.gov.my/Relevant_News-@-One_Belt_One_Road-;_Kuala_Lumpur_is_Sitting_on_One_of_the_Prettiest_Spots_.aspx

Khoo, Ryan. “China’s ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiatives in Malaysia.” The Edge Property, Feb 1, 2016

http://www.theedgeproperty.com.sg/content/china%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%98one-belt-one-road%E2%80%99-initiatives-malaysia

Kozłowski, Krzysztof. “The New Great Game Revised: Regional Security in Post-Soviet Central Asia.” Warsaw School of Economics, (2014): 190-203

Larres, Klaus. “China and Germany: The Honeymoon is Over.” The Diplomat, Nov 16, 2017

http://thediplomat.com/2016/11/china-and-gemany-the-honeymoon-is-over/

Lau, Stuart. “Make China’s Belt and Road Initiative a Two-Way Street, Says German Consul General in Hong Kong.” South China Morning Post, Apr 10, 2016

http://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/economy/article/1935033/make-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-two-way-street-says

Li, Xin. “Silk Road can Find Common Ground with Eurasian Economic Union.” Global Times, Apr 26, 2015

http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/918736.shtml

Li, Ziguo. “Central Asia Embraces ‘One Belt, One Road’ Because of the Matched Interest.” (li yi gao du qi he, zhong ya re qing yong bao yi dai yi lu), Beijing Review, Jun 1, 2015

http://www.beijingreview.com.cn/caijing/201506/t20150601_800033793.htm

Linn J. F. “Central Asian Regional Integration and Cooperation: Reality or Mirage?” EDB Eurasian Integration Yearbook 2012

https://www.brookings.edu/wpcontent/uploads/2016/06/10-regional-integration-and-cooperation-linn.pdf

Liow, Tiong Lai. “Speech by YB Dato’ Sri Liow Tiong Lai, Minister of Transport, Malaysia, Boao Forum for Asia – Luncheon Speech One Belt One Road Strategy, Vision, Action Plan.” Boao Forum for Asia, Jun 11, 2015

http://www.asli.com.my/uploads/20150615173806_Dato%20Sri%20Liow%20Tiong%20Lai%20Speech-Bo%20Ao%20Forum.pdf

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of P.R. China. “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s Regular Press Conference on January 18, 2017.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC website, Jan 18, 2017

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/xwfw_665399/s2510_665401/2511_665403/t1431615.shtml

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of P.R.China. “Xi Jinping Meets with President Islam Karimov of Uzbekistan.” Ministry of Foreign Affairs website, May 20, 2014

http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/yzxhxzyxrcshydscfh/t1158604.shtml

Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation. “Sergey Lavrov’s Remarks and Answers to Media Questions at a News Conference on the Results of Russian Diplomacy in 2016.” The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Russian Federation website, January 17, 2017

http://www.mid.ru/en/foreign_policy/news/- asset_publisher/cKNonkJE02Bw/content/id/2599609

Mohan, C. Raja. “Silk Route to Beijing.” Indian Express, Sept 15, 2014

http://indianexpress.com/article/opinion/columns/silk-route-to-beijing

National Development and Reform Commission of P.R.China. “Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road.” NDRC website, Mar 08, 2015

http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/201503/t20150330_669367.html

Shtraks, Greg. “China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative and the Sino-Russian Entente: An Interview with Alexander Gabuev.” The National Bureau of Asian Research, Aug 9, 2016

http://www.nbr.org/research/activity.aspx?id=707

Wilson, Jeanne. “The Eurasian Economic Union and China’s Silk Road: Implications for the Russian–Chinese Relationship.” European Politics and Society, 17:sup1, (2016): 113-132, DOI: 10.1080/23745118.2016.1171288

Xing, Guangcheng, and Weiwei Zhang. “Promote the Building of Sino-Uzbeki ‘One Belt, One Road’.” (tui jin zhong guo wu zi bie ke yi dai yi lu jian she), China Social Science Net, Feb 10, 2017

http://www.cssn.cn/sjs/sjs_rdjj/201702/t20170213_3412851.shtml

Xinhua. “China, Malaysia Vow to Promote Bilateral Relationship.” Xinhuanet, Oct 8, 2014

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-10/08/c_133698261.htm

Xinhua. “China Uses Cooperation on Regional Ports to Boost China-Mongolia-Russia Economic Corridor.” (zhong guo jie qu yu kou an he zuo zhu tui zhong meng e jing ji zou lang jian she), Xinhuanet, Jun 18, 2015

http://news.xinhuanet.com/fortune/2015-06/18/c_1115658858.htm

Xinhua. “China, Uzbekistan to Strengthen Cooperation Under the Silk Road Initiative.” Xinhuanet, Jun 15, 2015

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-06/15/c_134328727.htm

Xinhua. “Chinese, Uzbek Leaders Hail Inauguration of Central Asia’s Longest Railway Tunnel.” Xinhuanet, Jun 23, 2016

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-06/23/c_135458470.htm

Xinhua. “China, Uzbekistan Agree to Focus on Belt and Road Development.” Xinhuanet, Jun 22, 2016

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2016-06/22/c_135458277.htm

Xinhua. “Interview: Europe to Benefit from China’s One Belt, One Road Initiative: EC Chief.” Xinhuanet, May 7, 2015

http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-05/07/c_134218780.htm

Xinhua. “Sino-German Trade Reaches a New Level Based on Mutual Benefit.” (hu li gong ying, zhong de mao yi zai shang xin tai jie), Xinhuanet, Mar 14, 2017

http://news.xinhuanet.com/world/2017-03/14/c_129508816.htm

Yu, Bin. “China-Russia Relations: Putin’s Glory and Xi’s Dream, Comparative Connections.” Comparative Connections, Vol 15, Issue 1, Jan 2014

Bingxing Zhao is currently a graduate student of the department of political science, University of Windsor, Canada. Prior to his study in this university, he used to work for Chinese government and an American multinational company.