China’s Migrant Worker Poetry

This essay examines a relatively new genre in Chinese literature: migrant worker poetry. These are poems written by rural migrant workers who have, since the economic reform and opening up of the early 1980s, moved to China’s booming cities in search of work in factories, mines and construction. The difficulties that these workers face are manifold, from exploitation of their labor and lack of welfare protection to an inability to make their voices and hardships heard. How best to represent this vast and oppressed demographic (an estimated 280 million rural migrants) has been at the heart of China’s social and political debate for the last 30 years. I argue that migrant worker poetry has been both overlooked and underestimated, not only for its emergent quality, but for its ability to address problems of representation – these worker poets eloquently represent themselves.

By making use of online platforms they not only bear witness to the damaging myth of social mobility that motivates so many to seek work on the assembly lines, but they are able to challenge it directly, publishing their own sublimated suffering for each other and for society at large. The scope of this study is limited to the poems in Iron Moon, a 2017 anthology of migrant worker poems translated into English by Eleanor Goodman; it excludes novels, short stories or autobiographies by migrant workers that could be included in the wider genre of “worker literature”. I hope, however, that an examination of these poems demonstrates that the simultaneous emergence of the internet with China’s rapid industrialization has both created and enabled a vital new movement in the history of China’s working-class literature.

It’s hard to think of anywhere in the world where becoming a poet is a canny career move, but this is especially true for the poorest and most disadvantaged trying to gain a foothold in the factories of China’s frenzied special economic zones.

There have been a flurry of documentaries in recent years highlighting the hardships of China’s migrant workers, but the 2015 film Iron Moon drew attention to a very specific figure: the migrant worker poet. It follows several young writers battling economic and cultural prejudice in their attempts to sublimate 14-hour shifts on assembly lines into lines of poetry.

We see the young, tender-minded Wu Niaoniao (whose given name means Blackbird) wandering from stand to stand in Guangzhou’s vast strip-lit Southern China Job Market, enquiring about editorial positions on internal factory newspapers. With a knowing mix of fatalism and hope that seems to permeate the poetry of China’s migrant workers, he reads a poem and awaits their responses with a sheepish smile.

“I know young people want to follow their dreams, but…” says one cynical recruiter without finishing the sentence. Another peers over his glasses and enquires “but what do you do? You can make a lot of money with an education. Without an education you can’t do business, get it?”

One recruiter simply wonders if Wu ever considered writing things that were a little more upbeat.

While no one would expect construction and factory tycoons to be on the look out for the next Charles Bukowski, their collective response, paying lip service to impersonal pragmatism and business savvy, inadvertently reinforces Wu’s humble, unprofitable ambitions.

The plight of rural migrants is not new to Chinese fiction. The New Culture Movement of the 1910s and 20s, driven by concerns about how to modernize China and highlight those marginalized by the old feudal society, inspired Lu Xun, arguably the greatest Chinese writer of the 20th century, whose pioneering use of vernacular Chinese in The Real Story of Ah Q detailed the life of a rural peasant in the city. He was followed by Lao She’s rural orphan in Beijing in Rickshaw Boy and Zhang Leping’s long-running cartoon serialization of the “aimless drifter” San Mao in the 30s and 40s. And yet, these were still migrant stories written at a remove. And even though the three decades of revolution that followed enforced the centrality of the worker, peasant and soldier in fiction, it produced for the most part a state-controlled literature that did little to convey the lived experiences of those it claimed to represent.

That all changed in the 1980s. Since China’s reform and opening era of agricultural de-collectivization, privatization of industry and the formation of a self-styled socialist market economy, it is estimated that 274 million Chinese migrants have moved from the countryside to work in mines, construction sites, and urban assembly lines. It is not surprising, therefore, that the migrant worker has also become the central protagonist in China’s New Left Critique in which the term “subaltern” or diceng (i.e. “lower strata”) specifically focuses upon this new post-socialist figure: the rural-worker-in-the-city who lives on the sharp edge of market capitalism.

Once celebrated by the Communist revolution, political terms such as “the working people” (laodong renmin), the working masses (laodong dazhong) or simply workers (gongren) have been replaced by increasingly pejorative nomenclature. The migrant worker (mingong, yimingong, nongmingong) is someone who does not belong. This “floating population” (liudong renkou) by definition lacks agency. With mass layoffs in state enterprises in the late 1990s, growing numbers of rural migrant workers and disadvantaged urban workers have again become people who “work for the boss” (dagongzai, dagongmei – male and female workers respectively), a retrograde step in the quest for subjectivity and autonomy.

This rapid degradation of the laborer’s (laodongzhe) status, stripped of lifetime employment and bereft of many of the welfare benefits and the security of an earlier generation of state workers, is skillfully captured in a poem by former construction worker Xie Xiangnan. Here a young migrant compares the glorious image of “Lenin on the Rostrum” from his school days with the sight of forlorn hordes of migrants at the Guangzhou railroad station, carrying their possessions in plastic bags “like packages of explosives.” And again in the last lines of Ji Zhishui’s “Old World” in which “freedom’s great victory/in the end meant having nothing.”

Zheng Xiaoqiong’s “In the Hardware Factory” addresses directly the absurdity of old hopes and dreams:

I haven’t made it to the 21st century’s low slope of prosperity

the mountains are so high, but the body rots; how many years will it take

to reach utopia, I pity myself as I age

unable to squeeze aboard communism’s last train

but living in a scorching workshop in a sweatshop

(…) time begins to defect

it laughs at our memories and enthusiasm as they slip away

In the early post-socialist years, such disenchantment wasn’t always there. Migrant worker literature and poetry (which must not be confused with the official “worker poetry” of the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution) was one of many genres to sprout in the cultural wasteland following Mao’s death in 1976. But unlike the better-known elite (and beguilingly named) genres of “scar literature” and “misty poetry”, it’s one that, until recently, has been largely overlooked.

Early migrant worker literature mainly reflected a continued allegiance to state policy. In the early 80s, this meant formulaic self-help narratives of success-through-hard work in line with the government’s drive towards urbanization, of which Anzi’s Posthouse of Youth: The True Life of Migrant Women in Shenzhen is perhaps the most impressive. (Anzi became a model female migrant worker, whose entrepreneurial success in Shenzhen, site of the first China’s Special Economic Zone, codified the urban dream as reality.) Her legacy has been so influential that some critics have prematurely concluded that working girl (dagongmei) fiction such as this proves that women workers do not in fact lack agency. Unsurprisingly, these autobiographies and stories of social mobility in Shenzhen were also embraced by newspapers and state-run TV channels as handy proof that those rural workers who bore the heaviest burdens of the country’s early economic transformation were also its beneficiaries.

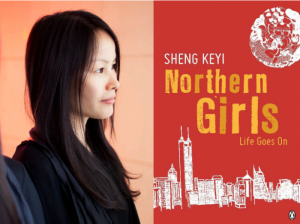

In 2004, the migrant worker-turned-writer Sheng Keyi transformed these narratives of plucky dagongmei ambition into one that upset government censors with its racy content and scenes of forced sterilizations in her critically and commercially acclaimed autobiographical novel Northern Girls. The headstrong albeit naïve protagonist, 16-year-old Qian Xiaohong, whose large breasts and demanding libido make her the target of unwanted male attention, courageously fights exploitative employers, corrupt policemen and crooked officials, refusing to let her body be appropriated or commodified. Despite staying true to her resolute moral code as she works her way up from salon girl to hospital administrator, the emotional and near metaphysical collateral damage of these years in Shenzhen leaves a heavy cloud hanging over the novel’s final pages. In the work of most recent migrant poets, this fatalistic bleakness is there from the start.

As Xie Xiangnan laments in his poem “Production, the Middle of Production, Is Soaked by Production,” reality doesn’t accord so neatly with one’s hopes:

This is a rectangular dream

Which inevitably brings forth a rectangular waiting

a floating country can’t pillow a broken dream

and I’ve never dared say goodnight to this enormous world.

Today the most famous migrant worker poet is 24-year-old Xu Lizhi who committed suicide in 2014. He worked at the Foxconn electronics mega-factory in Shenzhen famed not only for manufacturing Apple products and those of other international electronic giants, but for a spate of suicides in 2010 that exposed the sinister myth of opportunity and social mobility on the assembly line: “To die is the only way to testify that we ever lived,” wrote one blogger at the factory. (Foxconn subsequently erected netting to prevent not the despair but the death toll.) But when Xu threw himself from the seventeenth floor of a building four years later, having published much of his work online, it was not his death that made headlines, but his achievements as a poet.

Time magazine published his brief life story alongside his work under the headline: “The poet dying for your phone”. In China, the host of a national culture show marveled at the depths of this uneducated worker’s feelings. In giving shape to his experiences through poetry, Xu highlighted our own automated disconnect from the people who manufacture the clothes we wear and the electronics we consume, as conveyed in the final lines of his poem “Terracotta Army on the Assembly Line”:

(…) these workers who can’t tell night from day

wearing

electrostatic clothes

electrostatic hats

electrostatic shoes

electrostatic gloves

electrostatic bracelets

all at the ready

silently awaiting their orders

when the bell rings

they’re sent back to the Qin.

In 1956 Erich Fromm warned that “the danger of the past was that men became slaves. The danger of the future is that men may become robots.” Robot-like human slaves—dubbed iSlaves—are fueling the growth of Apple and other transnational corporations. Migrant workers in Xu’s poetic universe represent both the entombed foot soldiers of the ancient Qin dynasty and, when at work, the automata of the future. They have become the dehumanized, chillingly synchronized embodiment of Fritz Lang’s once futuristic Metropolis.

The plight of young rural migrants has not been ignored by the country’s higher profile authors. At the heart of recent critical literary debates in China have been the imperatives of “working class literature” or diceng wenxue – fiction that is both concerned with the conditions of ordinary people and takes a critical stance towards the society that oppresses them. Wang Anyi for example, one of the many young intellectuals to be sent down to the countryside during the Cultural Revolution, is an author whose focus has historically been largely about people like herself, other intellectuals (notably in The Song of Everlasting Sorrow and Love in a Small Town). But in 2000 she shifted focus to those on the periphery with her Shanghai migrant narrative Fuping. Can Xue, a writer best known for her experimental narrative style and subject matter also changed tack with her story The Migrant Worker Corps (mingongtuan). Both writers broke rank with their usual experimental narrative modes, resorting instead to a realism in keeping with a tradition set in motion by the May Fourth Movement as the literary technique that could most accurately convey social transformation and lower class lives.

However, when it comes to debates regarding who can and can’t speak on behalf of the diceng or lower classes, even intellectuals and authors who wish to contribute to this particular genre can still, as Gayatri Chakravorky Spivak argues, be complicit in “the muting” of worker voices. Which is what makes migrant worker poetry so valuable – as literature by and about workers that conveys a sense of their struggles, hopes and torments.

In spring 2017 the first translated anthology of migrant worker poetry was published. The book, also called Iron Moon, was compiled to accompany the documentary, both of which were curated by the poet and critic Qin Xiaoyu. Expertly translated by Eleanor Goodman (whose translations have been used for this essay), the collection includes work by 31 poets drawn from more than 100 in the Chinese original. These young migrant poets debunk the myth of social mobility; they are aware of their own exploitation. Since the mid-90s, their experience of powerlessness has fortified their literature with a fresh, compelling strength and honesty. The title, a visual metaphor taken from one of Xu Lizhi’s most well-known poems:

I swallowed iron

they called it a screwI swallowed industrial wastewater and unemployment forms

bent over machines, our youth died youngI swallowed labor, I swallowed poverty

swallowed pedestrian bridges, swallowed this rusted-out lifeI can’t swallow any more

everything I’ve swallowed roils up in my throatI spread across my country

a poem of shame

Given the primacy of the moon in classical Chinese poetry – as an image of solitude, of longing, of romance, of companionship – linking it with iron, says Goodman, conjures “a head-on collision of traditional Chinese culture with an explosion of capitalism, of humanity with mechanization, romance with an unromantic world – it becomes an amalgam of extremes. And these poets are dealing with this very consciously.” They are using poetic imagery, in line with China’s most treasured and esteemed classical art form, to counter the brutalizing experience of modernity.

More than a thousand years ago two of China’s most beloved Tang dynasty poets, Li Bai and Du Fu, pondered the moon’s ability to evoke a longing for home and distant family in “Quiet Night Thought” and “Moonlit Night”. Today, for several of these migrant poets, its eerie illumination during ghostly nightshifts becomes an equally melancholy companion. In Hubei Qingwa’s “Moon’s Position in the Factory,” it’s an inhuman co-worker: “under the moon,” he writes, “I regret my entire life.” Alu sees the moon as a “chunk of homesick iron”, a kindred loner, longing for its origins. Zheng Xiaoqiong sees it as a lonely light that obscures rather than exposes suffering:

And the tears, joy, and pain we’ve had

our glorious or petty ideas, and our souls

are all illuminated by the moonlight, collected, and carried afar

hidden in rays of light no one will notice.

Zheng, one of the finest poets in the collection, has pioneered her own distinctive “aesthetic of iron”, a peculiarly expansive and pliable metaphor to convey a life that is mercilessly cold and hard. Having worked for years in a die-mold factory and as a hole-punch operator, it is clear from the opening lines of “Language” how seamlessly she forges the physical and intellectual symbiosis of man and metal:

I speak this sharp-edged, oiled language

of cast iron–the language of silent workers

a language of tightened crimping and memories of iron sheets

a language like callouses fierce crying unlucky

hurting hungry language back pay of the machines’ roar occupational diseases

language of severed fingers life’s foundational language in the dark place of unemployment

between the damp steel bars these sad languages

……….. I speak them softly

It’s a theme that pervades the collection, including miner Chen Nianxi’s “Demolition’s Mark,” in which he writes,

“I don’t often dare look at my life/it’s hard and metallic black/angled like a pickaxe.”

Just as there is a noticeable splicing of rich, sophisticated imagery in some poems and a lean, resolute use of the vernacular in others, there are fascinating common themes: a nostalgia for a life not lived, the futility of language (“we can’t bear to put our tears and pain into our letters…. The blank spaces of years” writes Xie), a mourning for lost limbs and one’s truncated youth: “My finest five years went into the input feeder of a machine,” Xie records.

“I watched those five youthful years come out of the machine’s/asshole – each formed into an elliptical plastic toy.”

Just as the industrial revolution in England enforced a whole new concept of time, severing workers from seasonal rhythms, so these poets speak of disrupted menstrual cycles, damaged fertility, the blurring of night and day and the sense of unbelonging, where both countryside and city are rendered uninhabitable (several refer to themselves as “lame ducks”, maimed and unable to complete their journey back home).

The missed youth of their children, left behind with grandparents in country villages while they futilely try to make their way in the city haunts several of the poets. Chen Nianxi splices beautifully the small distances he covers down a mineshaft with the vast expanse his work puts between him and his family:

your dad is tired

each step is only three inches wide

and three inches take a year

son, use your math to calculate

how far your dad can go

At times, there is no greater reminder of solitude than an application form. Without a credible address or residence permit, without qualifications, connections or verifiable recommendations, this blank page is a visual exaggeration of their hopelessness. Alu writes of the feelings hidden behind tyrannical facts:

Ideas: He suddenly thinks of fire. The shadows penetrate his thoughts.

Education: The shadows begin to flee. The stars twinkle.

Place of birth: He shuts the window, hides in a suitcase and sobs.

Language is often, ironically, perceived as an insufficient tool. Of the poets who write about the severing of limbs – seven in total in this collection – all evoke the silent fatalism with which injury is experienced. Pain, both physical and emotional, leaps out from these pages.

Of course, migrant worker writers are not the only ones concerned with the spiritual vacuum of China’s brutish capitalist economy or the devastating destruction of the environment, but what makes their poetry so vital is that they are not writing from a distance, but at the coalface, at the cutting edge of the assembly line.

They work hellish hours without job security, drink water from rivers infused with pollutants, inhale air fouled by poisonous gases. They risk injury from merciless, vampiric machines that consume not only their youth, but their body parts (with numerous incidents of severed fingers). And they find the time outside of the interminable shifts and the space in their crowded dorm rooms to engage, to write about their lives and publish online using a basic cell phone (of the many forums they use, the most established is the Worker’s Poetry Alliance.) The internet has not only helped to raise awareness of what is happening to them, it has galvanized them to take action and make others aware of their adversity. In April 2017, I am Fan Yusu, a memoir published by a female migrant worker in Beijing on the online platform Noonstory.com became an overnight sensation, praised for the ability of its “sincere and simple words” to resonate with ordinary people. Having left her daughters in Hubei to work as a nanny for a rich tycoon’s mistress she wonders how the children of migrant workers can be protected from becoming “screws in the world’s factory” and being “lined up like Terracotta warriors, leading a puppet-like life” (translation from What’s on Weibo). Although the life stories of the rich and famous such as Alibaba magnate Jack Ma still monopolise the nonfiction market, Fan Yusu’s candid account, shared more than 100,000 times within 24 hours of posting before being deleted, could suggest that people’s awareness is also broadening to those on the margins. What’s indisputable is that the confluence of China’s industrialization with easy internet access has created an unprecedented opportunity for the creation and dissemination of working class literature, a literature by and for workers.

“No one, of course, would envy this opportunity. Xu Lizhi’s father, who still mourns his son’s death three years on, has little faith in the ability of poetry to improve the lives of the lower classes – spiritually or economically: “If this [his death] hadn’t happened,” he says tearfully in the documentary, “we wouldn’t” know he wrote poetry. But I don’t think there’s any future in poetry. It can’t compare with science and technology. Poetry was important in dynastic times, when it was part of the civil service exam… you could be an official if you wrote good poetry. But society has changed a lot. It’s not that I don’t support him, but in today’s world if you don’t have money or power it’s really hard.”

As Goodman points out, these poets not only face discrimination as unskilled workers, they are up against “a really deep prejudice that someone who doesn’t have a formal education can’t write poetry. Poetry has always been an essential part of the formal education structure; it was part of the civil service exams. When you talk to people in China there is a sense that someone is cultured or not-cultured – to broader society these workers are “uncultured.”’ Yet some of these worker poets are gaining a wide audience among workers and beyond.

The more “intellectual” writers of the Chinese avant-garde such as Mo Yan, Han Dong, Su Tong, Yu Hua, and Can Xue have turned to a Kafka-esque surrealism or magical realism to broach thorny subjects.

By contrast, in reading Iron Moon, one realizes how intimate and personal these young migrant writers can be, even when their writing is at its most dispassionate and restrained. In “Obituary for a peanut” Xu Lizhi’s presentation of the label on a jar of peanut butter becomes metamorphic in light of its title. For others, the language is wonderfully evocative, whether it’s Alu recalling his childhood (“The quiet nights/ were like a pine cone lying in the grass”) or Chi Moshu’s depiction of perverted circadian rhythms: “The stars are all asleep/and the 24-hour machines are still there/like sleeping babies shaken awake.” Their micro-narratives of mechanization, as self-identified screws, filaments, nails, discarded rocks, atoms of dust, unite as a powerful chorus. For they are, as Xie contends below, writing for themselves and each other:

Let’s have more

poets like Xie Xiangnan

they don’t come from storm clouds above

but from the belly of the earth

from those workers just stopping for the day

carrying shovels and hammers, from that sloppily dressed

group of men.

Their poems offer a deeper and more meaningful connection between the grand narrative of economic prosperity and the unheard stories of the millions who sacrifice their health, youth and sanity for our benefit.

One of the most forgiving and hopeful of the migrant worker poets is Wu Xia, whose disarming benevolence towards beneficiaries of her labor is heartbreaking:

I want to press the straps flat

so they won’t dig into your shoulders when you wear it

and then press up from the waist

a lovely waist

where someone can lay a fine hand

and on the tree-shaded lane

caress a quiet kind of love

last I’ll smooth the dress out

to iron the pleats to equal widths

so you can sit by a lake or on a grassy lawn

and wait for a breeze

like a flower

The very act of writing these poems is a way for those without a voice to counter the detachment they feel from each other, from their work, from the things they make, and to reclaim their own sense of humanity. It is also a communicative act, a cri de coeur, a call for social action. The personal is political: these poems can be read as searing critiques of an alienated epoch in which the state has sold out the rights of working people in return for foreign-investment fueled growth, in which labor and social protections are sacrificed. The poems also provide an opportunity for us not to lazily point fingers at China’s human rights abuses, but to think about our own casual complicity in these workers’ hardship. Their eloquent commitment to poetry and to life provides another way of understanding the cost of sweatshop labor that stretches beyond cold, unfeeling economics.

Iron Moon: An Anthology of Chinese Migrant Worker Poetry

Ed.: Qin Xiaoyu, Trans.: Eleanor Goodman White Pine Press, Buffalo New York

Iron Moon documentary (also known as The Verse of Us) dir. Qin Xiaoyu and Wu Feiyue

This is an expanded version of an essay that originally appeared on lithub.com

All images in this article are from the author except for the featured image which is from Oberlin College.