China’s Impressive Economic Growth. A Critical Look at China’s Belt and Road Initiative

Originally published: Reports from the Economic Front (October 2, 2018)

China’s growth rate remains impressive, even if on the decline. The country’s continuing economic gains owe much to the Chinese state’s (1) still considerable ability to direct the activity of critical economic enterprises and sectors such as finance, (2) commitment to policies of economic expansion, and (3) flexibility in economic strategy. It appears that China’s leaders view their recently adopted One Belt, One Road Initiative as key to the country’s future economic vitality. However, there are reasons to believe that this strategy is seriously flawed, with working people, including in China, destined to pay a high price for its shortcomings.

Chinese growth trends downward

China grew rapidly over the decades of the 1980s, 1990s, and 2000s with production and investment increasingly powered by the country’s growing integration into regional cross-border production networks. By 2002 China had become the world’s biggest recipient of foreign direct investment and by 2009 it had overtaken Germany to become the world’s biggest exporter. Not surprisingly, the Great Recession and the decline in world trade that followed represented a major challenge to the county’s export-oriented growth strategy.

The government’s response was to counter the effects of declining external demand with a major investment program financed by massive money creation and low interest rates. Investment as a share of GDP rose to an all-time high of 48 percent in December 2011 and remains at over 44 percent of GDP.

But, despite the government’s efforts, growth steadily declined, from 10.6% in 2010 to 6.7% in 2016, before registering an increase of 6.9% in 2017. See the chart below. Current predictions are for a further decline in 2018.

Beginning in 2012, the Chinese government began promoting the idea of a “new normal”—centered around a target rate of growth of 6.5%. The government claimed that the benefits of this new normal growth rate would include greater stability and a more domestically-oriented growth process that would benefit Chinese workers.

However, in contrast to its rhetoric, the state continued to pursue a high grow rate by promoting a massive state-supported construction boom tied to a policy of expanded urbanization. New roads, railways, airports, shopping centers, and apartment complexes were built.

As might be expected, such a big construction push has left the country with excess facilities and infrastructure, highlighted by a growing number of ghost towns. As the South China Morning Post describes:

Six skyscrapers overlooking a huge, man-made lake once seemed like a dazzling illustration of a city’s ambition, the transformation of desert on the edge of Ordos in Inner Mongolia into a gleaming residential and commercial complex to help secure its future prosperity.

At noon on a cold winter’s day the reality seemed rather different.

Only a handful of people could be seen entering or exiting the buildings, with hardly a trace of activity in the 42-storey skyscrapers.

The complex opened five years ago, but just three of its buildings have been sold to the city government and another is occupied by its developer, a bank and an energy company. The remaining two are empty–gates blocked and dust piled on the ground.

Ordos, however, was just one project in China’s rush to urbanize. The nation used more cement in the three years from 2011 to 2013 than the United States used in the entire 20th century. . . .

Other mostly empty ghost towns can be found across China, including the Yujiapu financial district in Tianjin, the Chenggong district in Kunming in Yunnan and Yingkou in Liaoning province.

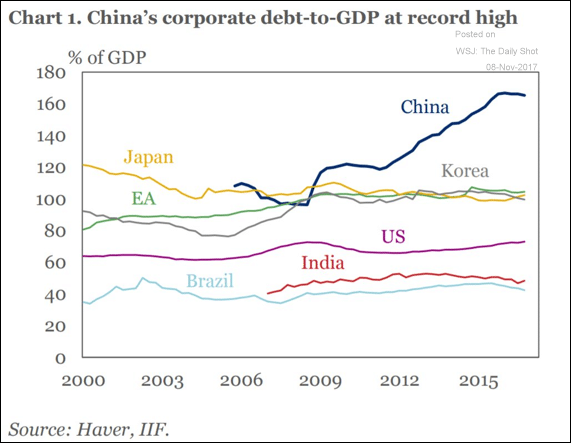

This building boom was financed by a rapid increase in debt, creating repayment concerns. Corporate debt in particular soared, as shown below, but local government and household debt also grew substantially.

The boom also caused several industries to dramatically increase their scale of production, creating serious overcapacity problems. As the researcher Xin Zhang points out:

Over the past decade, scholars and government officials have held a stable consensus that “nine traditional industries” in China are most severely exposed to the excess capacity problem: steel, cement, plate glass, electrolytic aluminium, coal, ship-building, solar energy, wind energy and petrochemical. All of these nine sectors are related to energy, infrastructural construction and real estate development, reflecting the nature of a heavily investment-driven economy for China.

Not surprisingly, this situation has also led to a significant decline in economy-wide rates of return. According to Xin Zhang:

despite strong overall growth performance, the capital return rate of the Chinese economy has started to be on a sharp decline recently. Although the results vary by different estimation methods, research in and outside China points out a recent downward trend. For example, two economists show that all through the 1980s and the first half of the 1990s, the capital return rate of the Chinese economy had been relatively stable at about 0.22, much higher than the U.S. counterpart. However, since the mid-1990s, the capital return rate experienced more ups and downs, until the dramatic drop to about 0.14 in 2013. Since then, the return to capital within Chinese economy has decreased even further, creating the phenomenon of a “capital glut”.

In other words, it was becoming increasingly unlikely that the Chinese state could stabilize growth pursuing its existing strategy. In fact, it appears that many wealthy Chinese have decided that their best play is to move their money out of the country. A China Economic Review article highlights this development:

Since 2015, the specter of capital flight has been haunting the Chinese economy. In that year, faced with the threat of a currency devaluation and an aggressive anti-corruption campaign, investors and savers began moving their wealth out of China. The outflow was so large that the central bank was forced to spend more than $1 trillion of its foreign exchange reserves to defend the exchange rate.

The Chinese government was eventually able to dam up the flow of capital out of its borders by imposing strict capital controls, and China’s balance of payments, exchange rate and foreign currency reserves have all stabilized. But even the largest dam cannot stop the rain; it can only keep water from flowing further downstream. There are now several signs that the conditions that originally led to the first massive wave of capital flight have returned. The strength of China’s capital controls might soon be put to the test.

Chinese leaders were not blind to the mounting economic difficulties. Limits to domestic construction were apparent, as was the danger that unused buildings and factories coupled with excess capacity in key industries could easily trigger widespread defaults on the part of borrowers and threaten the stability of the financial sector. Growing labor activism on the part of workers struggling with low salaries and dangerous working conditions added to their concern.

However, despite earlier voiced support for the notion of a “new normal” growth tied to slower but more worker-friendly and domestically-oriented economic activity, the party leadership appears to have chosen a new strategy, one that seeks to maintain the existing growth process by expanding it beyond China’s national borders: its One Belt and One Road Initiative.

The One Belt, One Road Initiative

Xi Jinping was elected President by the National People’s Congress in 2013. And soon after his election, he announced his support for perhaps the world’s largest economic project, the One Belt, One Road Initiative (BRI). However, it was not until 2015, after consultations between various commissions and Ministries, that an action plan was published and the state aggressively moved forward with the initiative.

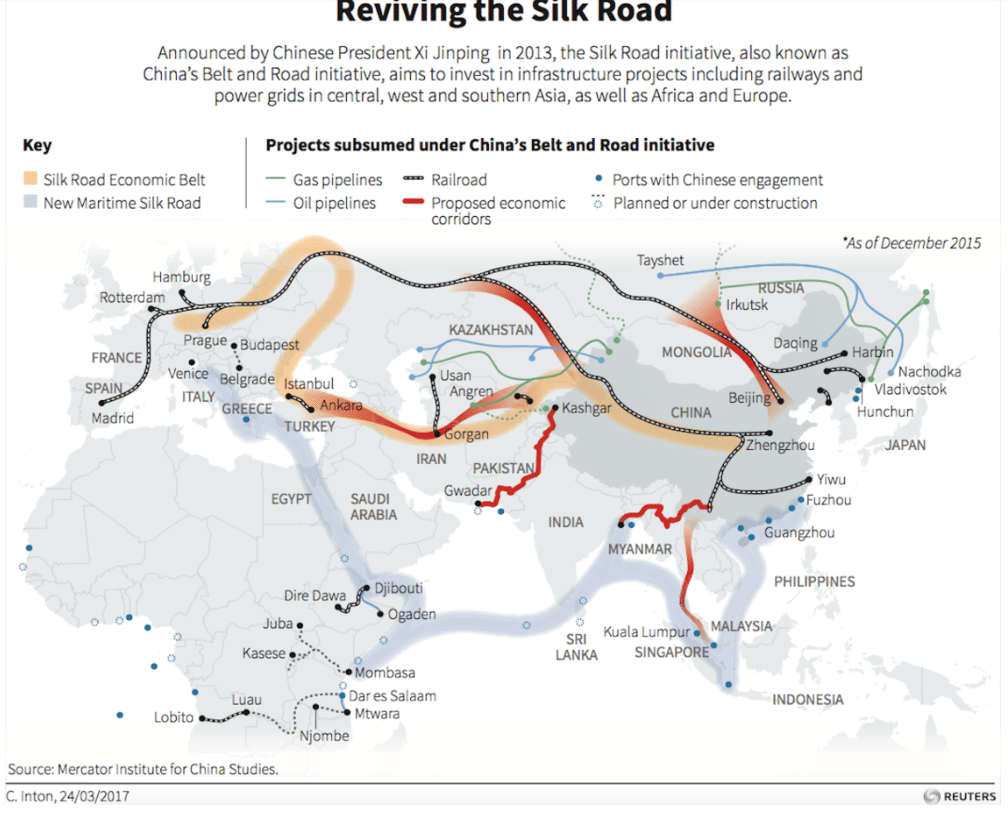

The initial aim of the BRI was to link China with 70 other countries across Asia, Africa, Europe, and Oceania. There are two parts to the initial BRI vision: The “Belt”, which seeks to recreate the old Silk Road land trade route, and the “Road,” which is not actually a road, but a series of ports creating a sea-based trade route spanning several oceans. The initiative was to be given form through a number of separate but linked investments in large-scale gas and oil pipelines, roads, railroads, and ports as well as connecting “economic corridors.” Although there is no official BRI map, the following provides an illustration of its proposed territorial reach.

One reason that there is yet no official BRI map is that the initiative has continued to evolve. In addition to infrastructure it now includes efforts at “financial integration,” “cooperation in science and technology,”, “cultural and academic exchanges,” and the establishment of trade “cooperation mechanisms.”

Moreover, its geographic focus has also expanded. For example, in September 2018, Venezuela announced that the country “will now join China’s ambitious New Silk Road commercial plan which is allegedly worth U.S. $900 billion.” Venezuela follows Uruguay, which was the first South American country to receive BRI funds.

Xi’s initiative did not come out of the blue. As noted above, Chinese economic growth had become ever more reliant on foreign investment and exports. And, in support of the process, the Chinese government had used its own foreign investment and loans to secure markets and the raw materials needed to support its export activity. In fact, Chinese official aid to developing countries in 2010 and 2011 surpassed the value of all World Bank loans to these countries. China’s leading role in the creation of the BRICs New Development Bank, Asia Infrastructural Investment Bank and the proposed Shanghai Cooperation Organization Bank demonstrates the importance Chinese leaders place on having a more active role in shaping regional and international economic activity.

But, the BRI, if one is to take Chinese state pronouncements at their word, appears to have the highest priority of all these efforts and in fact serves as the “umbrella project” for all of China’s growing external initiatives. In brief, the BRI appears to represent nothing less than an attempt to solve China’s problems of overcapacity and surplus capital, declining trade opportunities, growing debt, and falling rates of profit through a geographic expansion of China’s economic activity and processes.

Sadly this effort to sustain the basic core of the existing Chinese growth model is far from worker friendly. The same year that the BRI action plan was published, the Chinese government began a massive crackdown on labor activism. For example, in 2015 the government launched an unprecedented crackdown on several worker-centers operating in the southern part of the country, placing a number of its worker-activists in detention centers. This move coincided with renewed repression of the work of worker-friendly journalists and activist lawyers. The Financial Times noted that these actions may well represent “the harshest crackdown against organized labor by the Chinese authorities in two decades.”

And attacks against workers and those who support them continue. A case in point: in August of this year, police in riot gear broke into a house in Huizhou occupied by recent graduates from some of China’s top universities who had come to the city to support worker organizing efforts. Some 50 people were detained; 14 remain in custody or under house arrest.A flawed strategy

To achieve its aims, the BRI has largely involved the promotion of projects that mandate the use of Chinese enterprises and workers, are financed by loans that host countries must repay, and either by necessity or design lead to direct Chinese ownership of strategic infrastructure. For example, the Center for Strategic Studies recently calculated that approximately 90% of Belt and Road projects are being built by Chinese companies.

While BRI investments might temporarily help sustain key Chinese industries suffering from overcapacity, absorb surplus capital, and boost enterprise profit margins, they are unlikely to serve as a permanent fix for China’s growing economic challenges; they will only push off the day of reckoning.

One reason for this negative view is that in the rush to generate projects, many are not financially viable. Andreea Brinza, writing in Foreign Policy, illustrates this problem with an examination of European railway projects:

If one image has come to define the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), China’s ambitious, amorphous project of overseas investment, it’s the railway. Every few months or so, the media praises a new line that will supposedly connect a Chinese city with a European capital. Today it’s Budapest. Yesterday it was London. They are the newest additions to China’s iron network of transcontinental railway routes spanning Eurasia. But the vast majority of these routes are economically pointless, unlikely to operate at a profit, and driven far more by political need than market demand. . . .

Chongqing-Duisburg, Yiwu-London, Yiwu-Madrid, Zhengzhou-Hamburg, Suzhou-Warsaw, and Xi’an-Budapest are among the more than 40 routes that now connect China with Europe. Yet out of all these, only Chongqing-Duisburg, connecting China with Germany, was created out of a genuine market need. The other routes are political creations by Beijing to nourish its relations with European states like Poland, Hungary, and Britain.

The Chongqing-Duisburg route has been described as a benchmark for the “Belt,” the part of the project that crosses Eurasia by land. (The “Road” is a series of nominally linked ports with little coherence.) But paradoxically enough, the Chongqing-Duisburg route was created before Chinese President Xi Jinping announced what has become his flagship project, then “One Belt, One Road” and now the BRI. It was an existing route reused and redeveloped by Hewlett-Packard and launched in 2011 to halve the time it took for the computing firm’s laptops to reach Europe from China by sea. . . .

Unlike the HP route, in which trains arrived in Europe full of laptops and other gadgets, the containers on the new routes come to Europe full of low-tech Chinese products—but they leave empty, as there’s little worth transporting by rail that Chinese consumers want. With only half the route effectively being used, the whole trip often loses money. For Chinese companies that export toys, home products, or decorations, the maritime route is far more profitable, because it comes at half the price tag even though it’s slower.

The Europe-China railroads are unproductive not only because of the transportation price, as each container needs to be insulated to withstand huge temperature differences, but also because Russia has imposed a ban on both the import and the transport of European food through its territory. Food is one of the product categories that can actually turn a profit on a Europe-China land run—without it, filling China-bound containers isn’t an easy job. For example, it took more than three months to refill and resend to China a train that came to London from Yiwu, although the route was heavily promoted by both a British government desperate for post-Brexit trade and a Chinese one determined to talk up the BRI.

Today, most of the BRI’s rail routes function only thanks to Chinese government subsidies. The average subsidy per trip for a 20-foot container is between $3,500 and $4,000, depending on the local government. For example, Chinese cities like Wuhan and Zhengzhou offer almost $30 million in subsidies every year to cargo companies. Thanks to this financial assistance, Chinese and Western companies can pay a more affordable price per container. Without subsidies, it would cost around $9,000 to send a 20-foot container by railway, compared with $5,000 after subsidies. Although the Chinese government is losing money on each trip, it plans to increase the yearly number of trips from around 1,900 in 2016 to 5,000 cargo trains in 2020.

Another reason to doubt the viability of the BRI is that a growing number of countries are becoming reluctant to participate because it means that they will have to borrow funds for projects that may or may not benefit the country and/or generate the foreign exchange necessary to repay the loans. As a result, the actual value of projects is far less than reported in the media. Thomas S. Eder and Jacob Mardell make this point in their discussion of BRI activities with 16 Central and Eastern European countries (the 16+1):

Numbers on Chinese investment connected to the Belt and Road Initiative tend to be inflated and misleading. Only a fraction of the reported sums is connected to actual infrastructure projects on the ground. And most of the projects that are underway are financed by Chinese loans, exposing debt-ridden governments to additional risks. . . .

Depending on the source, BRI is called either a 900 billion USD or an up to 8 trillion USD global initiative. Yet only a fraction of the lower number is backed up by actual projects on the ground. BRI investments in 16+1 countries are similarly plagued by confusion over figures and a tendency towards inflation.

Media reports often arrive at their figures for the sum of “deals announced” by collating planned projects based on vague Memoranda of Understanding (MoUs) and expressions of interest by Chinese companies. Many parties share an interest to push Belt and Road-related figures upwards: local officials in BRI target countries like to impress constituencies, journalists like to capture readers, and Chinese officials are keen to cultivate the hype surrounding BRI.

The Banja Luka–Mlinište Highway in Bosnia Herzegovina, for example, is strongly associated with 16+1 investment. Sinohydro signed a preliminary agreement on implementing the project in 2014, for 1.4 billion USD, and this figure was then widely reported in English-language media. Four years later, though, final approval for an Export-Import Bank loan financing the highway section was still pending. This highway is actually one of the projects emerging in the region that we have fairly good information on, but the preliminary nature of the agreement is not reflected in media reports on the project.

Also in 2014, China Huadian signed an agreement on the construction of a 500MW power station in Romania, reportedly for 1 billion USD. Talks faltered, appeared to resume in 2017, and there has been no progress reported since. It is unclear whether and when this project will materialize, but it is the sort of “deal” counted by those totting up the value of Chinese investment in 16+1 countries. An even larger figure–1.3 billion–was reported in connection with Kolubara B, though it was later claimed that a cooperation agreement with Italian company Edison had already been signed, three years prior to the expression of interest by Sinomach.

Another important point is that Chinese “investment” in the region–and this very clearly emerges from the MERICS database–often refers to concessional loans from Chinese policy banks. This is financing that needs to be paid back, with interest, whether the project delivers commensurate economic benefits or not.

As with Belt and Road projects elsewhere in the world, loans made by Beijing to CEE countries create potential for financial instability. Smaller countries, which might lack the institutional capacity to assess agreements (such as risks associated with currency fluctuation), are particularly vulnerable.

The Bar-Boljare motorway in Montenegro illustrates this point. It is being built by the China Road and Bridge Corporation (CRBC) with an 809 million EUR loan from Exim Bank. The IMF claims that, without construction of the highway, Montenegro’s debt would have declined to 59% of GDP, rather than rising to 78% of GDP in 2019. It warns that continued construction of the highway “would again endanger debt sustainability.”

The motorway is typical of many BRI projects in that it is being built by a Chinese state-owned company, using mostly Chinese workers and materials, and with a loan that the Montenegrin government must pay back, but which a Chinese policy bank will earn interest on. On top of this, Chinese contractors working on the highway are exempt from paying VAT or customs duties on imported materials.

Because of these investment requirements, many countries are either canceling or scaling back their BRI projects. The South China Morning Post recently reportedthat the Malaysian government decided to:

Cancel two China-financed mega projects in the country, the US$20 billion East Coast Rail Link and two gas pipeline projects worth US$2.3 billion. Malaysian Prime Minister said his country could not afford those projects and they were not needed at the moment. . . .

Indeed, Mahathir’s decision is just the latest setback for the plan, as politicians and economists in an increasing number of countries that once courted Chinese investments have now publicly expressed fears that some of the projects are too costly and would saddle them with too much debt.

Myanmar is, as Reuters reports, one of those countries:

Myanmar has scaled back plans for a Chinese-backed port on its western coast, sharply reducing the cost of the project after concerns it could leave the Southeast Asian nation heavily indebted, a top government official and an advisor told Reuters.

The initial $7.3 billion price tag on the Kyauk Pyu deepwater port, on the western tip of Myanmar’s conflict-torn Rakhine state, set off alarm bells due to reports of troubled Chinese-backed projects in Sri Lanka and Pakistan, the official and the advisor said.

Deputy Finance Minister Set Aung, who was appointed to lead project negotiations in May, told Reuters the “project size has been tremendously scaled down”.

The revised cost would be “around $1.3 billion, something that’s much more plausible for Myanmar’s use”, said Sean Turnell, economic advisor to Myanmar’s civilian leader, Aung San Suu Kyi.

A third reason for doubting the viability of the BRI to solve Chinese economic problems is the building political blowback from China’s growing ownership position of key infrastructure that is either the result of, or built into, the terms of its BRI investment activity. An example of the former outcome: the Sri Lankan government was forced to hand over the strategic port of Hambantota to China on a 99-year lease after it could not repay its more than $8 billion in loans from Chinese firms.

Unfortunately, Africa offers many examples of both outcomes, as described in a policy brief survey of China-Africa BRI activities:

In BRI projects, Chinese SOEs overseas are moving away from ‘turnkey’ engineering, procurement, and construction (EPC) projects, towards longer term Chinese participation as managers and stakeholders in running projects. China Merchants Holding, which constructed the new multipurpose port and industrial zone complex in Djibouti, is also a stakeholder and will be jointly managing the zone, in a consortium with Djiboutian port authorities, for ten years. Likewise, SOE contractors for new standard gauge railway projects in Ethiopia and Kenya will also be tasked with railway maintenance and operations for five to ten years after construction is completed. . . .

Beyond transportation, the BRI is spurring expansion of digital infrastructure through an “information silk road”. This is an extension of the ‘going out’ of China’s telecommunications companies, including private mobile giants Huawei and ZTE, who have constructed a number of telecommunications infrastructure projects in Africa, but also the expansion of large SOEs such as China Telecoms. China Telecoms has established a new data center in Djibouti that will connect it to the company’s other regional hubs in Asia, Europe, and to China, and potentially facilitate the development of submarine fibre cable networks in East Africa. . . .

Countries linked to the BRI, including Morocco, Egypt, and Ethiopia, have also been singled out [as] ‘industrial cooperation demonstration and pioneering countries’ and ‘priority partners for production capacity cooperation countries’; these countries have seen a rapid expansion of Chinese-built industrial zones, presaging not only greater trade but also industrial investment from China. . . .

However, the rapid expansion in infrastructure credit that the BRI offers also brings significant risks. Many of these large infrastructure projects are supported through debt -based finance, raising questions over African economies’ rising debt levels and its sustainability. For resource-rich economies, low commodity values have strained government revenues and precipitated exchange rate crises—both of which constrain a government’s ability to repay external borrowing.

In Tanzania, the BRI-associated Bagamoyo Deepwater Port was suspended by the government in 2016 due to lack of funds. The port was originally a joint investment between Tanzanian and Chinese partners China Merchants Holding, which would construct the port and road infrastructure, along with a special economic zone. While project construction has continued, funding constraints have meant that the government has had to forego its equity stake. This represents a case where African governments may risk losing ownership of projects, as well as the long-term revenues they bring.

Adding to political tensions is the fact that many BRI projects “displace or disrupt existing communities or sensitive ecological areas.” It is no wonder that China has seen a rapid growth in the number of private security companies that serve Chinese companies participating in BRI projects. In the words of the Asia Times, these firms are:

Described as China’s ‘Private Army.’ Fueled by growing demand from domestic companies involved in the multi-trillion-dollar Belt and Road Initiative, independent security groups are expanding in the country.

In 2013, there were 4,000-registered firms, employing more than 4.3 million personnel. By 2017, the figure had jumped to 5,000 with staff numbers hovering around the five-million mark.

What lies ahead?

The reasons highlighted above make it highly unlikely that the BRI will significantly improve Chinese long-term economic prospects. Thus, it seems likely that Chinese growth will continue to decline, leading to new internal tensions as the government’s response to the BRI’s limitations will likely include new efforts to constrain labor activism and repress wages. Hopefully, the strength of Chinese resistance to this repression will create the space for meaningful public discussion of new options that truly are responsive to majority needs.