China Will Shake the Whole World: About Farmers and Artificial Intelligence

For the first time in recent history, a poor, underdeveloped country has in no time developed into an economic superpower, with a major impact on world affairs. How has this been made possible? What does this mean for the rest of the world? A retrospective of 70 years of Chinese revolutions.

Back on the world map

For centuries, China exerted a cultural attraction and was, together with India, a leading player on the world stage. After a century of harrowing colonization, humiliation and internal civil wars, Mao Zedong put his country back on the world map in 1949. The Chinese regained their dignity.

It was the start of a ‘development marathon at a great pace’ that would shake up global relations. And as Napoleon Bonaparte predicted earlier:

“China is a sleeping giant. When it awakens, the whole world will shake “.

Economic miracle

At the time of the establishment of the People’s Republic of China in 1949, the country was one of the poorest and most backward in the world. The vast majority of the Chinese were employed in (often primitive) agriculture. Per capita GDP was half that of Africa and one sixth of that of Latin America. To give the revolutionary ideals of equality a chance in a highly hostile world environment, it was necessary to achieve rapid economic and technological growth. This was to take place over the next 70 years through a process of trial and error.

After an extremely introverted and turbulent period under Mao Zedong – in which controversial mass campaigns were launched such as ‘The Great Leap Forward’ and ‘The Cultural Revolution’ – Deng Xiaoping took up the torch in 1978. Almost immediately but cautiously, he launched economic reforms and established relations with numerous countries, including, remarkably, the United States.

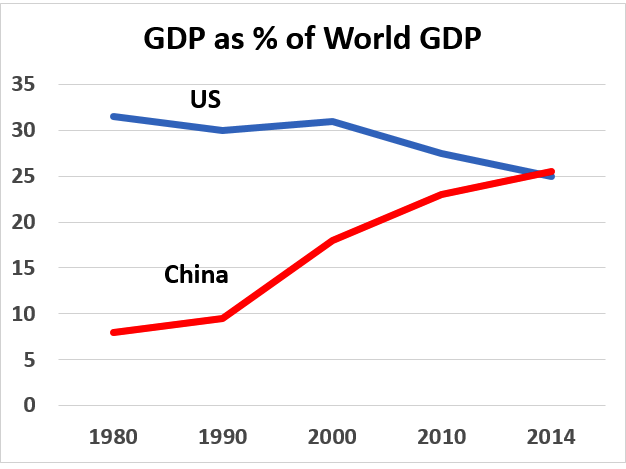

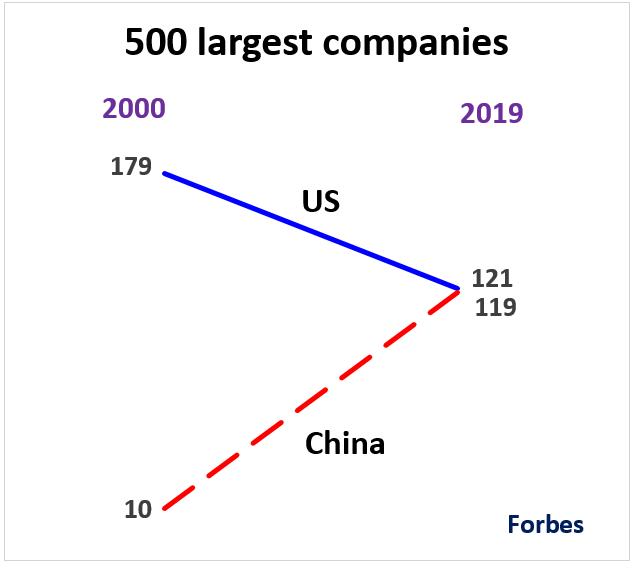

In comparison with Western Europe, China’s industrialization went four times as fast, and with a population five times as large.[i] Seventy years ago, the Chinese economy was insignificant on a global level. In 2014, the Chinese surpassed the US as the largest economy (in terms of volume) and it also becomes the largest exporting country. Today there are 35 Chinese cities with a GDP equal to that of countries such as Norway, Switzerland or Angola. The Chinese GDP has meanwhile become larger than the combined GDP of 154 countries. In 2011-2012, China produced more cement than the US during the entire twentieth century. It built ten new airports each year and has the world’s most extensive network of motorways and high-speed train lines. At the present, the country exports as much in six hours as it did in 1978 on an annual basis.

Technological leap forward

China is not only surprising in terms of quantitative evolution. In terms of quality, the Chinese economy has also made huge leaps forward, technological development being the prime example. Millions of engineers, scientists and technicians have graduated from Chinese universities in recent decades. Until recently, China was seen as an imitator of technology. Today it is a leading innovator. China currently has the fastest supercomputer and is building the world’s most advanced research center to develop even faster quantum computers. In recent years, the country has achieved impressive results in the field of hypersonic rockets, human gene processing tests, quantum satellites and perhaps most importantly: artificial intelligence. The Made in China 2025 project aims to strengthen that technological innovation in vital socio-economic sectors.

Does China owe part of its technological progress to the stealing of intellectual property? Undoubtedly, as is the case with countries such as Brazil, India and Mexico. In the past, the US, too, has only been able to develop its economic growth at the level of superpower thanks to the large-scale theft of technology from Great Britain and Europe. As The Economist puts it:

“The transfer of know-how from rich countries to poorer ones, by hook or crook, is an integral part of economic development.”

Recipe

The success of the Chinese modernization sprint is based on various pillars:

- The key sectors of the economy are in the hands of the government, which also indirectly controls most of the other sectors, inter alia through the controlling presence of the Communist Party in most medium-sized and large companies.

- The financial sector is under strict government control.

- The economy is planned, not in all details but in general, both in the short term and in the longer term.

- There is room for (quite a lot of) private initiative within a well-delineated market mechanism that is dynamically developed in various economic domains; the market mechanism is tolerated as long as it does not interfere with economic and social objectives (of the overall planning).

- Compared to other emerging countries, there is a high degree of openness to foreign investment and foreign trade, provided that it is in line with China’s global economic objectives.

- A great deal of effort is being put into developing infrastructure and Research & Development.

- Wages largely follow the increase in productivity, which has created a large and dynamic internal market.

- A relatively large amount is invested in education, health care and social security.

- The country has enjoyed peace for decades and there is a relatively high level of social peace in the workplace.

- The distribution of agricultural land to farmers at the start of the revolution and the system of individual household registration (Hukou) have made it relatively possible to avoid the typical chaotic rural exodus of most Third World countries, resulting in massive informal and unproductive work.

- Unlike the Soviet Union, China has not embarked on a very expensive arms race with the US.

This approach contrasts with the recipe of capitalist countries where financial capital and multinationals are in charge, where short-term profit is the overriding goal and where governments are fixated on eliminating budget deficits through savings. The spectacular way in which they have tackled the financial crisis (2008) is typical of China. The Chinese government launched a stimulus program of 12.5 percent of GDP, probably the largest peacetime program ever. The Chinese economy plummeted a little but then picked up quickly, while the European economy has been teetering during ten years.

New growth model

Due to rapid changes in the internal labor market, wages and foreign markets, the Chinese government developed a different growth model. When President Xi Jinping took office in 2012, he stated that ‘growth for growth’s sake’ should no longer be the goal. The old model was based on exports and on investments in heavy industry, construction and the manufacturing industry. In the new model, the driving force is mass consumption (domestic market), the services sector and higher added-value activities by climbing the technological ladder. This transformation illustrates the flexibility in which the Chinese leadership implements economic policy. It is the 12th pillar of the Chinese recipe. This flexibility stands out from the way the Soviet Union dealt with these challenges in its later period.

Can the successful growth continue for a while now? Without doubt the economy is struggling with a high level of debt, shadow banks, over-investment in infrastructure, a real estate bubble, an ageing population, an increasing trade war with the US, and so on. Yet most observers still see China as a resilient economy with analyses showing that there is still substantial room for error and setbacks and a lot of room to grow at a rapid pace for a long time to come.

The largest poverty reduction in world history

In 1949, at the start of the Chinese revolution, the life expectancy was 35 years. Thirty years on, it had already doubled to 68 years.[ii] Today, the life expectancy of the Chinese is 76 years. Infant mortality has improved fairly well. If, for example, India offered the same medical care and social support to its inhabitants as China does, 830,000 fewer Indian babies would die each year.[iii]

Between 1978 and 2018 China succeeded in lifting a record number of people out of poverty: 770 million. This amounts to the total population of sub-Saharan Africa during that period. At the current pace, extreme poverty will be eradicated by 2020. According to Robert Zoellick, former President of the World Bank,

this is “certainly the greatest leap to overcome poverty in history. China’s efforts alone have ensured that the world’s Millennium Development Goal on poverty reduction will be met. We and the world have much to learn from this.”

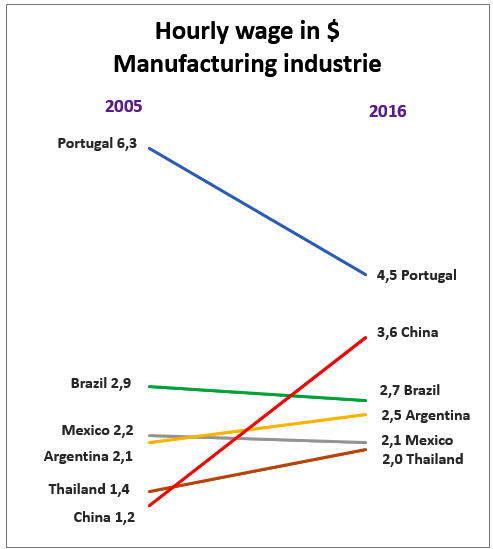

While wages are stagnating or declining in many countries, they have tripled in China over the last decade. Fifteen years ago, Western multinationals flocked to China because of low wages. The reverse movement is now starting to take hold. The average wages in the Chinese industry are currently only 20 percent lower than in Portugal. Countries such as Bulgaria, Macedonia, Romania, Moldova and Ukraine already had lower minimum wages in 2013 than in China.

Dark sides

This success story also has its drawbacks. The faster increase in productivity in industry and services, compared to agriculture, has led to a big gap between urban and rural areas, between poorer regions and the richer eastern coastal provinces. The strict Hukou system (registration of the individual residence, determines the social status) causes a huge group (of hundreds of millions) of ‘internal migrants’ who have less social rights and are often being discriminated. The one-child policy (since 1978) has led – apart from its binding character – to numerous selective abortions and a male surplus of more than thirty million.

Democracy: input and output

The Western political system usually thinks of itself to be superior and regards itself as the only valid model. This doesn’t demonstrate much historical insight knowing that almost all fascist regimes were born in the womb of western parliamentary democracy. An unbiased observer also will observe that Western democracy mainly serves the interests of the 1 %. That it lacks both a long-term vision and an effective policy to tackle social and ecological problems. And that it has been the breeding ground for increasingly ludicrous, unpredictable and dangerous figures such as Trump, Johnson, Bolsonaro and Duterte.

When it comes to democracy, the emphasis in the West is on the input side, on the question of how and by whom decision-making takes place. What are the procedures for choosing the political leadership and is the will of the citizens voiced by the elected representatives? Elections are the most important element in this.

In China, the emphasis is on the outputside, i.e. on the consequencesof the decision: is the decision successful and who benefits? The result is paramount, good and fair governance is the most important criterion.[iv] In this respect, the Chinese attach more importance to the quality of their politicians than to the procedures for choosing their leaders.

Political decision-making with Chinese characteristics

According to Daniel Bell, expert on the Chinese model, China’s political system is a combination of meritocracy at the top, democracy at the base and room for experimentation at the intermediate levels. The political leaders are selected on the basis of their merits and, before they reach the top, they go through a severe process of training, practice and evaluation. There are direct elections at the municipal level and for the provincial party congresses. Political, social or economic innovations are first tried out on a smaller scale (a few cities or provinces) and after thorough evaluation and adjustment introduced on a large scale.[v] According to Daniel Bell, that combination “comes close to the best formula for governing a large country”.

In addition, the central government organizes opinion pollson a very regular basis which assess the government’s performance in the areas of social security, public health, employment and the environment. The popularity of local leaders is also the subject of the surveys. Based on this, policies are frequentlyadjusted.

The Chinese decision-making system has proved its worth. Francis Fukuyama, who can hardly be suspected of left-wing or Chinese sympathies:

“The most important strength of the Chinese political system is its ability to make large, complex decisions quickly, and to make them relatively well, at least in economic policy. China adapts quickly, making difficult decisions and implementing them effectively.”

For example, in just two years, China has extended the pension system to 240 million rural residents, which exceeds drastically the total number of people covered by the US state pension system.

It should therefore come as no surprise that the Chinese government can count on great support from the population. Around 90 percent say their country is heading in the right direction. In Western Europe, that is between 12 percent and 37 percent (the global average).

The Communist Party

The backbone of the Chinese model is the Communist Party. With more than 90 million members, it is by far the largest political organization in the world. That such a backbone is useful or even necessary is shown by the gigantic proportions of the country. China is the size of a continent: it is 17 times the size of France and has as many inhabitants as Western Europe, Eastern Europe, the Arab countries, Russia and Central Asia combined. Translating this into the European situation would mean that Egypt or Kyrgyzstan would have to be governed from Brussels. Given these proportions, the large differences between the regions and the huge challenges facing the country, a strong cohesion force is needed to keep the country governable and to be able to implement a solid policy. According to The Economist:

“China’s rulers believe the country cannot hold together without one-party rule as firm as an emperor’s (and they may be right).”

The party recruits the most skilled people. The selection process for the promotion of top leaders is objective and rigorous. Kishore Mahbubani, a top expert on Asia:

“Far from being an arbitrary dictatorial system, the CPC may have succeeded in creating a rule-bound system that is strong and durable, not fragile and vulnerable. Even more impressive, this rule-bound system has thrown up possibly the best set of leaders that China could produce.”

Nearly three quarters of the population say they support the one-party system.

International relations

China’s economy has been largely self-sufficient in the past. It has been able to afford to live in isolation from the outside world and has often done so. Even at the height of its imperial power, China has spread its culture by diplomatic and economic relations rather than by (military) conquests.[vi] This way of foreign policy is also maintained in recent history. China strives for a multipolar world, characterized by equality between all countries. It regards sovereignty as the cornerstone of the international order and rejects any interference in the internal affairs of another country, for whatever reason. This often gives China the reproach that it does too little against human rights violations in other countries. In any case, China is the only permanent member of the UN Security Council that has not fired a single shot outside its own borders in the last 30 years.

Globalization in Chinese style

Today, China is no longer self-sufficient. With 18 percent of the world’s population, it has only 7 percent of the world’s arable farmland, and only imports 5 percent of the world’s oil. In addition, the country produces far more goods than it consumes. For all these reasons, China today is highly dependent on world markets.

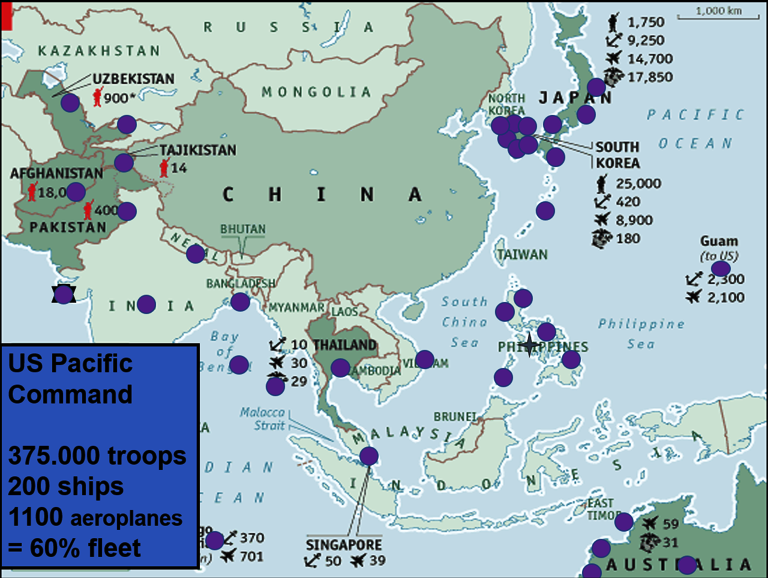

China’s dependence on world trade and the – in essence – military ‘encirclement’ of the US (see below) has prompted the country to take the initiative for a New Silk Road. Two thousand years ago, during the Han Dynasty, the world-renowned Silk Road connected China to the Mediterranean Sea via Eurasia. Like the historic trade route, the project has also become a vast network of sea and land routes today, launched in 2013 under the name of ‘One Belt, One Road’.

In the meantime, more than 1,600 projects are involved in construction and infrastructure works, projects in transport, air and other ports, but also in initiatives of cultural exchange. Hundreds of investments, loans, trade agreements and dozens of Special Economic Zones, worth 900 billion dollars, are spread over 72 countries, representing a population of approximately 5 billion people or 65% of the world’s population. ‘One Belt, One Road’ is by far the largest development program since the Marshall Plan for post-World War II reconstruction in Europe.

Martin Jacques describes the New Silk Road as “Globalization in Chinese style”. The ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative is strongly reminiscent of the Netherlands’ trade strategy 400 years ago. British and French colonialism were literally on the hunt for conquered land. They organized military conquests to subdue societies and to steal wealth. Amsterdam, on the other hand, was striving for an ’empire of trade and credit’. It was not about territory but about business. The Dutch built a gigantic fleet, installed trading posts on the major routes and then tried to secure them. Like the Dutch in the 17th century, China currently has the largest merchant fleet.[vii] The Special Economic Zones are “commercial garrisons of a supply chain world, enabling China to secure resources without the messy politics of colonial subjugation” says Stratfor, a prestigious think tank.

Tilting North-South relations

China’s enormous growth in the heart of Asia has acted as a catalyst for the entire continent. The world’s economic centre of gravity is shifting rapidly towards the poorer economies of Asia. It also dramatically increases the demand for raw materials, to the benefit of many countries in Latin America and Africa.

The industrialization of East Asia shows the pattern of ‘flying geese’. As a country upgrades economically, wages rise and less sophisticated production tasks shift to poorer regions with lower labor costs. This first happened in Japan, then in South Korea and Taiwan, and today this process is in full swing in China. Because of the higher wages, Chinese companies are now relocating their production to countries such as Vietnam and Bangladesh, but also increasingly to Africa. If this trend continues, it can help to build an industrial base on the African continent.

Confronting the US

The socialist revolutions did not break out in the heart of capitalism but in its weakest links, the poorest and most underdeveloped countries. An advanced social system then had to be built on a weak material basis, which has given rise to many handicaps and contradictions. Seventy years later, that situation has changed radically. China’s great leap forward in technology and spectacular economic growth have laid solid foundations for building a socialist society.

Of course, Washington is not amused with this. But even worse is the fact that China threatens to surpass the US economically. These two phenomena feed the ‘new Cold War’ between the US and China and the threat of a ‘hot war’.

In the context of the 2019 budget discussions, Congress stated that “long-term strategic competition with China is a principal priority for the United States”. It is not only about economic aspects, but about an overall strategy that must be conducted on several fronts. The aim is to maintain dominance in three areas: technology, the industries of the future and armaments.

Trump is aiming for a full reset of the economic relations between the US and China. The growing trade war is the most striking, but it is only the leading edge of a larger strategy that includes investment, both Chinese investment in the US and US investment in China. In the first place the strategic sectors are targeted with the aim of disrupting China’s technological advance. In this respect, the roll-out of the 5G network is crucial. It is no coincidence that the Huawei, which is far ahead in the development of 5G technology, has become a central target.

The Trump government is also trying to extend this economic war with China to other countries by having clauses signed in trade agreements or by simply putting pressure on them. The aim is to create a kind of “economic iron curtain” around the country.

US military strategy

The military strategy towards China has two tracks: an arms race and an encirclement on the country.[viii] The arms race is in full swing. The US spends 650 billion dollars a year on weapons, or more than a third of the world total. That is 2.6 times as much as than China and 11 times as much as per capita. It also spends 150 billion dollars a year on military research, that’s five times as much as China. The Pentagon is feverishly working on a new generation of highly sophisticated weapons, drones and all kinds of robots, which a future enemy will not be able to cope with. A pre-emptive war is not excluded.

The second track is the military encirclement. For its foreign trade, China depends for 90 percent on maritime transport. More than 80 percent of the oil supply has to pass through the Strait of Malacca (near Singapore), where the US has a military base. Washington can easily cut off oil flows to China. Currently the country has no defence against it. Around China the US has more than thirty military bases, facilities or training centres (dots on the map). 60 percent of the total US fleet is stationed in the region. It is no exaggeration to say that China is encircled and squeezed. You can not imagine what would happen if China were to install even one military facility, let alone a base near the US.

It is in this context that China’s militarisation of small islands in the South China Sea should be seen as well as its claim to a large part of this maritime area. Controlling the shipping routes along which its energy and industrial goods are transported is of vital importance to Beijing. It is in that same context that the New Silk Route must be seen.

Champion of pollution and greening

Since the end of the 1980s, China has entered a phase of development that has caused great environmental pollution. As the ‘workplace of the world’, it is one of the biggest polluters on the planet. At present the country is also – by far – the largest emitter of CO2, albeit that the emissions per person are less than half of those of the US and about the same size as those of Europe. China is also responsible for only 11 percent of cumulative emissions, compared with more than 70 percent for industrialized countries.

The situation is untenable. At the current rate, between 1990 and 2050, China will have produced as much carbon dioxide as the whole world did between the beginning of the Industrial Revolution and 1970, and that is catastrophic for global warming.

Ten years ago, the Chinese leadership changed course and the ecological issues were given high priority. In 2014 the “War on Pollution” was declared by Prime Minister Li Keqiang. A battery of measures is being drawn up, including trend-setting legislation on the environment, but its application is not always self-evident.

The results follow quickly. In no time, China has become number one in the field of solar panels and wind energy. Currently, 33 percent of the electricity is generated by green energy, compared to less than 17 percent in the US. China today invests about as much in green technology as the rest of the world combined. It wants to capture and store millions of tons of CO2 underground in the near future.

The country is a pioneer in the long-distance transmission of large amounts of energy (e.g. from distant solar panel fields), which is very important for green energy supply of cities. According to NASA data, China’s sustained reforestation efforts have made an important contribution to the global forestation, which is essential to keep emissions under control. On the other hand, Chinese companies still have a large share of illegal logging worldwide.

Patron saint of the Paris Climate Agreement

China is called the ‘patron saint of the Paris Climate Accord‘ (COP 21, 2015, focus: limiting global warming to a maximum of 2 degrees, with 1.5 degrees as a target value). When Trump withdrew from the agreement in 2017, Beijing declared that it would do everything in its power to achieve the goals of COP21, together with others – including the EU.

China also acts as a mediator between rich industrialized countries and developing countries, stressing that global warming is essentially a historical responsibility of the industrialized countries, and therefore arguing that rich countries should make financial resources and technology available to developing countries in order to combat climate change. Thanks to China, the large majority of developing countries have aligned themselves with the objectives of COP21 and submitted climate plans to the UN General Assembly in recent months.

There is, obviously, still a long way to go in China but it is going in the right direction. Witness to this is the report in mid-2017 that China has achieved its climate targets two years before the agreed date of 2020. China is

Errors

Many mistakes have been made over the past seventy years. Initially, the CPC tried to introduce socialism hastily with the Great Leap Forward (1958-1961), with catastrophic consequences. The left-wing extremism of the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) left deep scars and led to a right-wing reaction. The introduction of market elements from 1978 onwards has given capitalist exploitation a controlled rein. The consequences were far-reaching: a deeper gap between rich and poor, and the creation of a top layer of capitalists.

The margin for personal enrichment has been widened and has caused rampant corruption and abuse of power. Nevertheless, this policy of ‘capitalist bird in the cage’ has made the Chinese economy grow spectacularly and has dramatically reduced extreme poverty. Whether this controlled market-oriented dynamic can be kept in check will remain to be determined by the future.

The Chinese leadership has succeeded in keeping the vast and very heterogeneous country together, but this was and is done by keeping certain minorities tightly in line. Tibetans and Uighurs feel treated like second-class citizens, even though there have been many formal efforts by the Chinese authorities to improve their situation. Quite a few questions remain about the unorthodox and muscular approach to ethnic tensions.

An advantage here is that the Chinese leadership is not in the habit of hiding or concealing weaknesses and problem issues. They are usually explicitly recognized and addressed. For example, before and during the eighteenth Congress, the country’s main problems were listed one by one and discussed and translated each with action points assigned. Such a rational political attitude makes it possible to learn from the mistakes and, if necessary, to adjust the course.

Stability of the planet

For the first time in recent history, a poor, underdeveloped country has rapidly developed into an economic superpower, with a major impact on world affairs. China, and in its wake India, is rapidly changing the balance of powers and transforming the world in an unprecedented way.

The more China follows an independent course, the more it deviates from the West and the more it holds up a mirror to ‘the Western system’, the more the country is criticized and attacked. It seems to be very difficult for us to look at this new world player in an open-minded way. According to Mahbubani, “the reluctance of Western leaders to acknowledge that Western world domination cannot continue is a major threat”.[ix]

Yet we will have to learn to live with the realization that we are no longer the center and benchmark of the world. In fact. With the rise of populism in more and more countries, unpredictable and irresponsible people like Trump, Bolsonaro or Johnson are taking the reins. The stability and liveability of this planet will increasingly depend on people like Xi Jinping and other decent leaders.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Notes

[i] We take 1870 as a starting year for Western Europe and 1980 for China. We measure the speed of the industrialization process based on the growth of GDP per capita. The figures are calculated on the basis of Maddison A., Ontwikkelingsfasen van het kapitalisme, Utrecht 1982, p. 20-21 en UNDP, Human Development Report 2005,p. 233 en 267. Zie ook The Economist, 5 januari 2013, p. 48.

[ii] Hobsbawm E., Een eeuw van uitersten. De twintigste eeuw 1914-1991, Utrecht 1994, p. 540.

[iii] Calculated on the basis of UNICEF, The State Of The World’s Children 2017, New York, p. 154-155.

[iv] For the distinction between input and output of political decision-making, see Kruithof J., Links en Rechts. Kritische opstellen over politiek en kultuur, Berchem 1983, p. 66.

[v] Bell D., The China Model. Political Meritocracy and the Limits of Democracy, Princeton 2015, p. 179-188.

[vi] Luce E., The Retreat of Western Liberalism, New York 2017, p. 166.

[vii] In the seventeenth century, the Netherlands had 25 times more ships than England, France and Germany. Today, China has 20 times more merchant ships than the US. Maddison A., The World Economy. A Millennial Perspective, OESO 2001, p. 78; Khanna P., Use It or Lose It: China’s Grand Strategy, Stratfor,9 april 2016.

[viii] For a more extensive treatment, see Vandepitte M., Trump and China: Towards a Cold or Hot War?

[ix] Mahbubani K., De eeuw van Azië. Een onafwendbare mondiale machtsverschuiving, Amsterdam 2009, p. 18.

All images in this article are from the authors