China and India in Central Asia: Competition or Convergence?

It is quite probable that India’s growing role in Central Asia via its US-approved Chabahar Corridor to the region will lead to increased competition with China there. But there is also the possibility that the two Asian Great Powers’ connectivity projects could pragmatically converge in this region. This will usher in the admittedly unlikely scenario of a Eurasian Renaissance if New Delhi breaks ranks with Washington due to irreconcilable economic disagreements stemming from Trump’s so-called ‘trade war’.

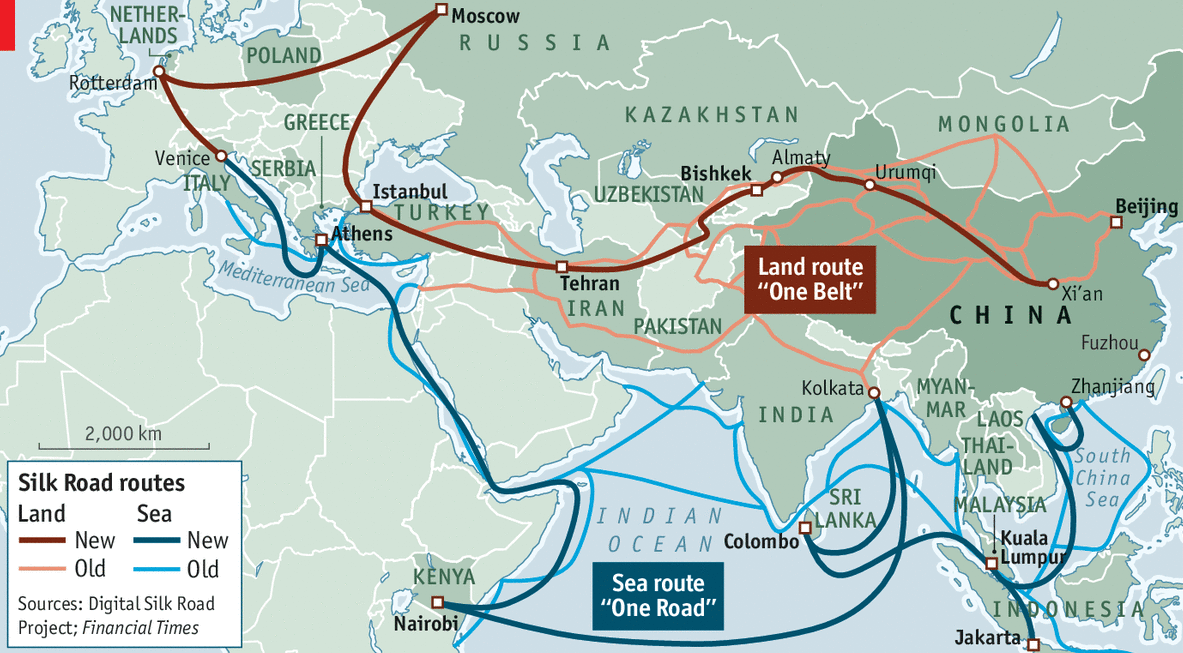

Central Asia, the focal point of Zbigniew Brzezinski’s ‘Grand Chessboard’ is more relevant now than ever in the emerging Multipolar World Order with India set to challenge China for influence in this resource-rich space. The competition between the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative and the joint Indo-Japanese ‘Asia-Africa Growth Corridor’ connectivity projects is heating up after India secured a sanctions waiver from the US to expand its Iranian-based Chabahar Corridor into the region. It strongly suggests that the success of this initiative would advance America’s national security interests more than imposing the relevant sanctions on Iran. This observation pointedly speaks to the grand strategic significance that the US sees in facilitating India’s entry into Central Asia, even if Trump has to lessen the impact of his highly publicized anti-Iranian sanctions in order to have this happen.

The guiding notion behind this gambit is that the expected influx of Indian economic influence into Afghanistan and the former Soviet Republics of Central Asia could redirect regional trade routes away from China. This would allow New Delhi to cultivate its own local and national elite that have a financial stake in ensuring the success of India’s far-reaching American-assisted influence operation in this part of Eurasia. The US is willing to accept the residual economic and political benefits that Iran is slated to gain as a result of allowing its territory to be used for connecting India to the Central Asian region, wagering that it could nevertheless still be contained through the Damocles’ Sword of secondary sanctions if it gets out of hand. Furthermore, Iran’s deepening reliance on India as an anti-sanctions pressure valve enables America to indirectly influence its rival via Tehran’s relationship with its ally.

Acknowledging that the US is convinced (whether naively or not) that the pro-Iranian blowback that could result from this strategy is manageable, one can now proceed to analyzing the grander designs behind this approach. Washington understands that without India’s ‘economic intervention’ in the region, Central Asia will reliably remain under the influence of the multipolar great powers of Russia, China, Pakistan, Iran, and Turkey that comprise the Golden Ring. This is why the US is willing to sacrifice the ultimate impact of its promised anti-Iranian sanctions in the hopes that Tehran will agree to indirectly assist its plans in the region as an unofficial form of sanctions relief. This is not to suggest that Iran is knowingly conspiring with the US, but just that it has been pushed into the position where it believes that some of its interests are best served by collaborating with India on the American-approved Chabahar Corridor.

So long as Iran continues going along with this strategy, and there have thus far been no grounds to suspect that it would not, then it is inevitable that the regional countries’ growing economic relations with India will eventually lead to increased political relations with it. This could possibly be up to the point of breaking the de-facto Russian-Chinese condominium in Central Asia by introducing a so-called third force that could help its government balance between these two neighboring Great Powers. Russia no longer commands the economic influence that it once did in Central Asia. However, it can provide for the region’s security needs while China takes care of its economic ones. Viewed through a zero-sum perspective, this development would work out more to China’s relative detriment than anyone else’s. This is especially so when considering that Russia has excellent relations with India and is also inviting it to expand its investments in the Chinese-bordering Far East region. That is not to say that Russia is actively encouraging India to play a greater role in Central Asia, but just that it will flexibly adjust to this reality since it has no way of influencing this process one way or another.

One must bear in mind that the main artery of India’s connectivity investments in Iran is aimed at actualizing the North-South Transport Corridor for streamlining Russian-Indian trade via Iran and Azerbaijan. By dint of their geography, the two states that will probably see the most active competition between India and China are Afghanistan and Uzbekistan. For Afghanistan, Beijing previously suggested joint cooperation through the China-India-Plus-One format. Uzbekistan is an aspiring great power in its own right and eager to multi-align between the countries of the Golden Ring, India, and also the US. Interestingly enough, Pakistan is poised to play a role in all of this too.

There exists a realistic chance to expand CPEC into the region through three separate branches that could colloquially be called CPEC+, running from Gwadar to Chabahar and then up onwards, transiting via Afghanistan, and finally through Xinjiang in connecting Pakistan with its Babur-era civilizational cousins in Central Asia. The introduction of China’s all-weather ally Pakistan into the Central Asian competition could complement Beijing’s multipolar activities there and contribute to counteracting India’s influence, with the strategic consequence being that this landlocked region would then informally become part of the concept of greater South Asia. The impact of the Pakistani-Indian rivalry on Central Asia is impossible to predict in any precise terms, but it can broadly be forecast that it would remain within the non-kinetic sphere and restricted to economic, cultural, and informational dimensions.

Source: Economist

After all that has been analyzed thus far, it might seem like a fait accompli that India will soon flex its muscles as a disruptive force in Central Asia focused on shaking up the region’s affairs at the US’ balancing behest. But there still remains an unlikely possibility that an altogether different scenario might unfold which nevertheless cannot be discounted. The aforementioned analysis is premised on the presumption that India will remain one of the US’ top military-strategic allies this century, but in the off chance that irreconcilable economic disagreements over Trump’s so-called trade war push New Delhi to progressively distance itself from Washington in response, India could reverse some of the destabilizing effects that its entrance into Central Asia might otherwise have for the emerging multipolar world order.

To be clear, it would be altogether better for the Golden Ring if India did not play any role whatsoever in this construction of Central Asian Heartland. However, if it is inevitable that New Delhi will, then it is best for it to do so in coordination with Beijing through the China-India-Plus-One format that could potentially set the basis for merging their New Silk Road and ‘Asia-Africa Growth Corridor’ connectivity initiatives into a single developmental platform that could conceivably set the basis for a Eurasian Renaissance. Once again, it needs to be emphasized that it is extremely unlikely that this will happen because it would necessitate India having to defy the US’ presumably imposed primary and secondary sanctions against the Chabahar Corridor, but in the event that New Delhi garnered the political will to do so, then it could end up being a real game-changer.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Pakistan Politico.

Andrew Korybko is an American Moscow-based political analyst specializing in the relationship between the US strategy in Afro-Eurasia, China’s One Belt One Road global vision of New Silk Road connectivity, and Hybrid Warfare. He is a frequent contributor to Global Research.

Featured image is from Tehran Times