Chile’s 1973 Coup and Barack Obama’s Selective Memory on 9/11

Obama, referring to the military coup in Chile, stated in 2011 that we should not be “trapped by our history.”

At the September 11, 2016 ceremony, President Barack Obama remembered and honored the victims of terrorism. However, what was Obama’s position when he visited La Moneda in Chile in 2011, the presidential palace where the U.S.-organized military coup of September 11, 1973, took place?

Chile was the second leg of Obama’s March 2011 trip to Latin America. For the vast majority of people in Latin America, as well as many in North America and Europe, Chile invokes the atrocious events of 1973.

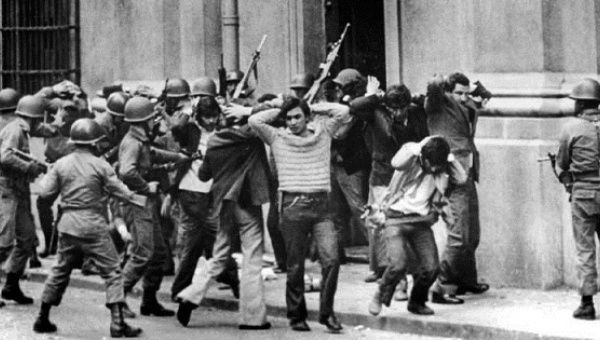

The military coup was directed against the democratically-elected socialist government of Salvador Allende. After the coup, tens of thousands of people were imprisoned, tortured, killed, forced into exile or disappeared. All left-wing socialist and communist organizations were violently suppressed. Allende, one of the icons of Latin American socialist and revolutionary personalities, himself died on that day in La Moneda Palace.

At La Moneda on March 21, 2011, Obama, along with his host, Chilean President Sebastian Piñera, addressed invited guests and some journalists at a press conference. In his opening remarks, Obama did not refer to the 1973 military coup nor, of course, to U.S. responsibility, but he did mention that Chile has “built a robust democracy.”

The US-orchestrated coup in Chile led to tens of thousands of people being imprisoned, tortured, killed, forced into exile or disappeared. | Photo: EFE

The first question asked by a journalist addressing Obama, despite his comments about transition to democracy, was, “In Chile … there are some open wounds of the dictatorship of General Pinochet. Political leaders, leaders of the world, of human rights, even MPs … have said that many of those wounds have to do with the United States … (is) the U.S. willing to collaborate with those judicial investigations … (is) the United States willing to ask for forgiveness for what it did in those very difficult years in the ’70s in Chile?”

In response to the correspondent’s question, Obama referred to the coup only as evidence of an “extremely rocky” relationship between the U.S. and Chile. This was followed by his statement that we should not be “trapped by our history,” that he “can’t speak to all of the policies of the past,” and repeated once again the importance of “understand(ing) our history, but not be(ing) trapped by it.”

In the same vein of avoiding the role of the U.S. in the 1973 coup, during another address in La Moneda several hours later, he was forced to make a vague reference to it. He referred to La Moneda as the place where “Chile lost its democracy decades ago.” He also made a frontal attack on Cuba.

He ignored the U.S. anti-communist orientation that motivated the 1973 coup against the Allende socialist government supported by the Chilean communists. Cuba and Allende’s Chile while had very fraternal relationships. Nevertheless, Obama vowed, “support for the rights of people to determine their own future—and, yes, that includes the people of Cuba.”

People should not be surprised by Obama’s selective use of history regarding the 1973 coup in Chile. Obama announced in his second book, to those who were interested in knowing, where he stands on the issue of military coups versus progressive or socialist thought and action.

He wrote, “At times, in arguments with some of my friends on the left, I would find myself in the curious position of defending aspects of Reagan’s world view. I didn’t understand why, for example, progressives should be less comfortable about oppression behind the Iron Curtain than they were about brutality in Chile.”

It is important for people to reflect seriously upon Obama’s manipulation of history and political content that is embedded in his use of the past. Together, they form the manner in which Obama and the U.S.-type of multi-party, competitive democracy use selective history with the goal of distancing themselves (in the case of Obama) from the previous administrations and, indeed, the entire history of U.S. military interventions in the hemisphere.

This process is carried out in order to provide a “new face” to U.S. intervention. This course of action even goes so far as to co-opt opposition to the decades-long U.S. policy so that this resistance applauds the new U.S. image under Obama. He goes to La Moneda, where the U.S. was responsible for the death of Allende.

Obama uses the hostility against the U.S.-organized coup and the pro-Allende sentiment by attempting to convert the resentment in favor of the U.S. by giving the impression that Washington is turning the page on its aggressive interference and thus the Chilean people can rely on the U.S. and Obama himself.

We recall, as mentioned above, Obama’s comment in his second book regarding his frustration about progressives and the left standing up against the coup in Chile. He juxtaposed this progressive political tendency to repression behind the Iron Curtain. Obama’s view on the Iron Curtain versus Chile reflects a very important traditional stance of U.S.-foreign policy.

Irrespective of one’s opinion on the former USSR and Eastern Europe, what has been the age-long policy of the U.S. since the 1917 October Revolution?

The course of action has been to support anything that opposes socialist, progressive and revolutionary ideas and actions. Taking the 20th century alone, there was the initial support for the fascists in Germany and Italy leading up to World War II, because it had in its crosshairs the USSR. There were also the innumerable, bloody undertakings in Latin America throughout the century—El Salvador, Guatemala, Cuba, Nicaragua, Brazil, Grenada, etc.—it is well known with whom the U.S. has always sided and against which forces it fought.

What remains a problem to be solved is that many people still turn a blind eye to Obama’s writings and utterances, a haziness caused by the U.S.-centric, prejudiced faith in the legend that the U.S. two-party system can really compete between programs of “change” and “status quo.”

Arnold August, a Canadian journalist and lecturer, is the author of “Democracy in Cuba” and the “1997-98 Elections” and, more recently, “Cuba and its Neighbours: Democracy in Motion.” Arnold can be followed on Twitter andFaceBook.