Che Guevara, Apostle of the Oppressed: Che and the Cuban Revolution

The fiftieth anniversary of the death of Che Guevara, assassinated in Bolivia on October 9, 1967, offers us an opportunity to look back on the Cuban-Argentine revolutionary who dedicated his life to defending the “Damned of the Earth”.

What was Che Guevara’s role in the Cuban Revolution?

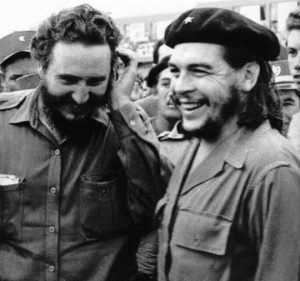

Che was one of the principal leaders of the rebel army, second-in-command to Fidel Castro who was the indisputable and undisputed leader of the July 26 Movement and the most emblematic figure of the Cuban Revolution. Che was on the same level as Raúl Castro, Camilo Cienfuegos, Ramiro Valdés and Juan Almeida, among others, but it was he who had the greatest intellectual affinity with Fidel Castro.

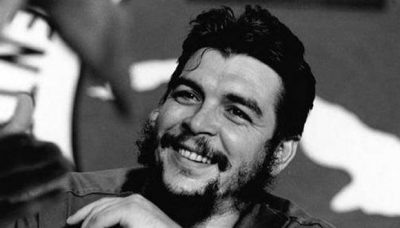

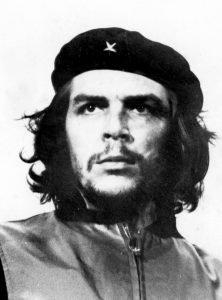

Che possessed extraordinary courage, that at times approached rashness, and felt a sovereign contempt for danger. His prestige spread rapidly among the fighting troops and supporters of the Movement across the island. Everyone knew that an Argentinian, with a funny accent, was fighting alongside Fidel, and his engagement won the admiration of the Cuban people. Although he was not as well known around the world as Fidel Castro, his image nevertheless had appeared several times in the international press, notably in the United States.

Che possessed extraordinary courage, that at times approached rashness, and felt a sovereign contempt for danger. His prestige spread rapidly among the fighting troops and supporters of the Movement across the island. Everyone knew that an Argentinian, with a funny accent, was fighting alongside Fidel, and his engagement won the admiration of the Cuban people. Although he was not as well known around the world as Fidel Castro, his image nevertheless had appeared several times in the international press, notably in the United States.

What were the circumstances under which Che was appointed commander by Fidel Castro?

Because of his exceptional qualities as a fighter, a fine strategist and his natural gift of leading men, Che Guevara was the first to be appointed commander, long before Raúl Castro. Argentinian by birth, Che had chosen to join the Cuban revolutionary movement to free the island from the military dictatorship of Fulgencio Batista, but importantly from the hegemonic control of the United States as well. He was aware that he would risk his life at every moment, given the dangers involved in a guerrilla war against an enemy immensely superior in number. Still, he quickly distinguished himself among the group of 82 insurgents by demonstrating his extraordinary valor. Whenever a dangerous mission presented itself, he was the first to volunteer. Understandably, he rapidly won the hearts and respect of his comrades, who greatly admired seeing a foreigner risk his life for a land that was not his own.

Fidel Castro had quickly discerned the exceptional virtues of Che and decided to promote him to the rank of Commander. The Argentinean learned of his promotion in the following way: On July 21, 1957, Fidel Castro ordered his brother Raúl to write a letter to Frank País, leader of the July 26 Movement of the province of Santiago de Cuba, on behalf of the entire group. As he included Che’s name among the signatories, Raúl asked his brother what title he should affix to it. The answer was: “Put ‘commander’”.

Was Che a doctor or guerrilla?

There is an anecdote that reveals Che’s state of mind on this subject. The voyage of the Granma, from Mexico to the Cuban coast, lasted seven days instead of the five originally scheduled. Rather than arriving in Cuba on November 30, the Granma reached the Cuban coast on December 2, 1956. In Santiago, a city in the eastern part of Cuba, an uprising had been planned on November 30 to divert attention and support the landing. Nevertheless, the army, informed of the revolutionaries impending arrival, was waiting for the expedition to land. Moreover, in addition to the grueling crossing, the guerrillas landed in the swampy area of Las Coloradas and the journey from the boat to the mainland was a nightmare that lasted for several hours.

There is an anecdote that reveals Che’s state of mind on this subject. The voyage of the Granma, from Mexico to the Cuban coast, lasted seven days instead of the five originally scheduled. Rather than arriving in Cuba on November 30, the Granma reached the Cuban coast on December 2, 1956. In Santiago, a city in the eastern part of Cuba, an uprising had been planned on November 30 to divert attention and support the landing. Nevertheless, the army, informed of the revolutionaries impending arrival, was waiting for the expedition to land. Moreover, in addition to the grueling crossing, the guerrillas landed in the swampy area of Las Coloradas and the journey from the boat to the mainland was a nightmare that lasted for several hours.

Only moments after their arrival, while in a state of total exhaustion, the insurgents were spotted by military aviation and pursued by soldiers of the dictatorship. The troop was therefore forced to disperse. Che, caught up in this whirlwind, had to make a choice. While he was appointed to be the group’s doctor, he found himself in possession of two large bags, the first filled with ammunition and the second with drugs. It was physically impossible for him to carry both while he was under fire. He therefore opted for the ammunition bag because he considered himself a revolutionary before being a doctor.

What was the name of Che’s battalion?

Che’s battalion was created following his promotion to commander. At the time, the only existing battalion was that of Fidel Castro which bore the designation Column No. 1. Logically, Che’s battalion should have been named Column No. 2, but in order to deceive the enemy regarding the importance of the revolutionary forces, Fidel decided to name it Column No. 4.

Later, Che was put in charge of the “Suicide Squad”, which consisted of the most experienced combatants whose role it was to carry out the most dangerous missions. Due to Che’s rather excessive temerity, Fidel decided to entrust him with responsibility for the group on the condition that he himself no longer participate in this type of operation and focus instead on strategic, tactical and organizational tasks.

The leader of the Cuban Revolution knew that the country would need this group of chosen and trained cadre, and that it was therefore vital to preserve it. On each mission, one or more fighters lost their lives, hence the name “Suicide Squad”. In his diary, Che recounts an unusual and recurring event: when a member of the suicide squad lost his life, another soldier was appointed to replace him. Each time, he witnessed scenes of young fighters in tears, disappointed not to have had the honor of joining a group that would have allowed them to demonstrate their bravery.

How did Che treat the prisoners?

Che was implacable with the rapists, the torturers, the traitors and the murderers. Revolutionary justice was expeditious. On the other hand, he made it a point of honor to preserve the life of the prisoners and to look after the enemy’s wounded. There were two reasons for this. The first was moral and ethical: the life of any prisoner was sacred and needed to be protected. The second was political in nature: while Batista’s army gave no quarter, torturing and murdering prisoners of war, the rebel army demonstrated its difference through its irreproachable conduct.

At the beginning of the revolutionary process, no soldier surrendered because all were convinced that they would be executed by the rebels. Towards the end of the insurrectional war, the soldiers of Batista, who had heard of the noble conduct of the insurgents, surrendered en masse when they were surrounded by the revolutionaries because they knew they would be safe.

An anecdote illustrates Che’s behavior on this subject: following a fight with the army, a rebel killed a wounded soldier without giving him a chance to surrender. He himself had lost everyone in his family during a bombing. Che went into a great rage and told him that his conduct was unworthy of the rebel army, that soldiers’ lives should be preserved whenever possible, and that none were to be shot. Hearing these words, another wounded soldier, who had hidden behind a tree, revealed his position by shouting “Do not shoot!”. He was treated by the rebels and every time a guerrilla appeared, he raised his arms and exclaimed: “Che has said that prisoners will not be killed!”

What was Che’s reputation?

Che was a leader of natural authority and prestige, acquired on the battlefield. He was demanding and steadfast. He preached not by word, but by example. He was uncompromising on principled matters and hated favoritism and special privileges. In the mountains of the Sierra Maestra, when a cook attempted to attract Che’s favor by filling his plate with more than what the other fighters had received, he immediately drew the wrath of Che, who cursed him out. He was egalitarian and wished to be treated like his fellow fighters. His prestige and the admiration of the Cuban people for him were born of his exemplary attitude. He was unyielding and hard, but fair and honest.

What were his political views during the triumph of the Revolution on January 1, 1959?

Che defined himself as a Marxist-Leninist. He already had a solid theoretical background before joining the Cuban revolutionary movement. From his experience in Guatemala, he had discovered how US economic hegemony was strangling Latin America and how it constituted an obstacle to any effort at social transformation. The Cuban situation, where the strategic sectors of the economy were in the hands of US multinationals, allowed him to realize that the struggle for freedom, equality and justice would also be a struggle against US imperialism. He was absolutely convinced that the state should take control of the country’s strategic resources by carrying out a vast agrarian reform, diversifying the economy and multiplying its trading partners in order to free itself from dependence upon its powerful northern neighbor. He believed it should also universalize access to education, health, culture and sport as well as provide unfailing support to those who are struggling for their dignity.

Salim Lamrani

Article in French :

Che Guevara, apôtre des opprimés: Le Che et la Révolution cubaine, October 11 2017

Translated from the French by Larry R. Oberg.

Source for the english article : huffingtonpost.com (La Réunion)

Doctor of Iberian and Latin American Studies at the Paris IV-Sorbonne University, Salim Lamrani is a lecturer at the University of La Réunion, specializing in relations between Cuba and the United States.

His new book is titled Fidel Castro, héros des déshérités, Paris, Editions Estrella, 2016. Preface by Ignacio Ramonet.

Contact: [email protected]; [email protected]

Facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/SalimLamraniOfficial