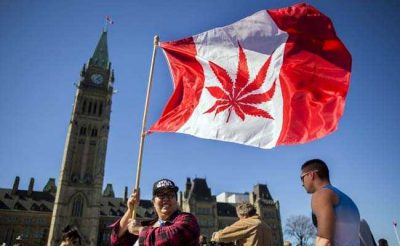

Canada: Starting Down the Path to Marijuana Legalization

In the late 1960’s my wife and I shared an eclectic circle of friends in London Ontario that included business colleagues, social workers, artists, university professors, hippies and students. We were starting a family and I was on the fringe of politics having volunteered to do fundraising and served on the public Library and Art Gallery Boards.

The hippie era was at its peak. Throughout North America, there was an active drug subculture that was at odds with the law. The enforcement tactics of the police in both the United States and Canada at the time were crude and unnecessarily alienating young people. Police were infiltrating hippie groups to search out drug use and this created paranoia.

Our friends who worked at the Addiction Research Foundation told us of the negative effect this was having on kids who were becoming fearful of police because the police were using spies and entrapment. A mantra at the time was, “Don’t trust anyone over thirty”.

Pierre Trudeau personified the period, as had John F. Kennedy a decade earlier, and he was elected Prime Minister in 1968. Trudeau’s charisma encouraged change, and this encouraged us.

In 1969, I established The Legalize Marijuana Committee with the sole purpose of lobbying the federal government for saner laws and became its spokesperson. We assumed that the government wanted feedback – probably even needed it – to discuss changing the law. We were right, and the government confirmed that in several ways.

First, they confirmed it by inviting us to meet with the federal Minister of Health and Welfare. Off we went to Ottawa. Only our immediate family knew where we were going or where we were staying.

We booked the cheapest room in the Chateau Laurier Hotel. When we checked in, the bellhop took us to the penthouse suite! It was a corner on the top floor of the hotel with outstanding views on two sides, four king size beds, a living room with several sofas and a kitchen area. Someone, it seems, had upgraded the room and paid the difference – this was the second bit of feedback that someone appreciated our efforts. (When we checked out, we paid the economy rate. Again, nothing was said.)

We booked the cheapest room in the Chateau Laurier Hotel. When we checked in, the bellhop took us to the penthouse suite! It was a corner on the top floor of the hotel with outstanding views on two sides, four king size beds, a living room with several sofas and a kitchen area. Someone, it seems, had upgraded the room and paid the difference – this was the second bit of feedback that someone appreciated our efforts. (When we checked out, we paid the economy rate. Again, nothing was said.)

Within a few minutes, a reporter called the hotel room telling us that someone had released our itinerary to the press as the reporters started calling – the government was leaving nothing to chance, they wanted the publicity.

The Minister’s office was on the top floor of an office building in Ottawa, a short walk from both the hotel and the Parliament buildings. We arrived a few minutes early to a modest reception area with about six others waiting. They didn’t hear us introduce ourselves. As we listened, it was clear from the conversations that they were journalists who were there because of us. “I wonder who these guys are” … “I see nothing wrong with it … I smoke the occasional joint” … “good luck to them!”

Soon we were asked to go in, and reporters fidgeted as they realized they had missed a chance to scoop a first interview. We were taken to a more private waiting room before John Munro, an energetic, chain-smoking Minister of Health and Welfare, welcomed us into his inner office. Several sofas circled a large coffee table and on the table was a file folder about eight inches thick, too deep to close. When Munro noticed it was sitting open he immediately closed it and put an ash tray on top.

We had sent him one letter and a small brochure, yet he had a file on us eight inches thick. Later, as I thought about the file, our hotel upgrade, and our schedule being released, I recalled that we had a break-in in our home a few weeks earlier. The break-in was a non-event; it would have been unnoticed except someone had broken the cheap lock on the only file cabinet in the house. Nothing was taken but in hindsight, I believe it must have been the Royal Canadian Mounted Police doing a routine report on someone about to meet a government minister on a contentious topic.

The government was using our group to float a trial balloon alerting the world that they were thinking of changing drug laws. After a few minutes, the press was invited in. About twenty journalists filled the office for about half an hour of Q and A. Then one of the journalists asked if we would agree to go to the Press Club on Parliament Hill where we met another thirty or so print journalists. An hour or so later we were taken to the media studio for TV and radio interviews by another dozen journalists.

Later the same year the Trudeau government took a step towards changing drug laws by establishing a Royal Commission (Royal Commissions are a big deal in Canada, like a Presidential Commission in the United States); The Commission of Inquiry into the Non-Medical Use of Drugs which stated in its title that the Government saw this as a civil rights and medical issue, not a criminal one.

The government appointed Gerald LeDain, a lawyer and Dean of Canada’s prestigious Osgoode Hall law school to head the commission which began with a public hearing on Oct. 26, 1969. For their opening day, they invited two organizations to appear: The Royal Canadian Mounted Police and our group, the Legalize Marijuana Committee. Each group presented a brief and the next day’s newspaper had a lead story on the hearing including two photos: one of the Commissionaire of the RCMP, and the other, me. (My mother wrote to the paper to get a copy of the photo, “… before my son goes to jail” as she stated!)

The official report recommended the repeal of laws against possession of cannabis and the prohibition of cultivation for personal use. One of the commissionaires went further, recommending a policy of legal distribution. Unfortunately, the Canadian Government ignored the report; I suspect it was because the government to our south opposed it.

Now, 48 years later, we have legalized marijuana in Canada.

The Economics of marijuana

At the heart of illegal drug distribution is pyramid selling. Mary Kay thrives on it but whether to sell cosmetics or illegal drugs, anyone can be hired and hire any number of sub-dealers. Everyone gets a cut, and the profit margins are high enough in cosmetic sales to award the occasional pink Cadillac. Profit margins for drugs are higher because they are illegal and the market more dangerous. The vehicles tend to be bigger, and black, and usually with tinted windows.

In 2003, I was a member of a Social Action Committee that was studying the ‘War On Drugs’ and supported a progressive resolution on Alternatives. I was invited to attend a national conference, and to prepare for it I updated myself on some 30 years of changes. I learned how much larger and more dangerous the illegal drug market had become.

At the conference I met Judge Jim Gray from the Superior Court in Southern California, who told me about how teenagers in his California town could get crack cocaine easier than beer, because, as he said, beer was legal and controlled. Privately, he told me how much he respected Judge Le Dain and the work he had done with the Canadian Commission.

How big is the illegal drug market? One answer can be found in the Caribbean.

The Cayman Islands: swimming in money

Grand Cayman Island is the largest of three Cayman Islands miles just south of Cuba. It’s a tropical paradise, where you can swim with stingrays in North Sound or take a submarine ride along the coral reef cliff on the south.

It’s about an hour or so by plane south of Miami, about two hours north of Columbia and two hours east of Mexico – therefore, central to two drug producing nations and the huge drug consuming market of the United States. Politically the islands are British Overseas Territories. They are not independent, not a country, and not truly British. They occupy a small area, one-quarter the size of New York City (102 vs. 468 sq. miles) with a small population of 57,000 people.

Over half of those people live in George Town, on Grand Cayman, and this tiny town is the fifth-largest banking center[1] in the world. There are 279 banks and 260 of them do no banking in the Caymans. With the Caymans’ unusual political structure, laws get strange and enforcement stranger. Drug lords can take a day trip to the Caymans, do some banking, avoid all taxes and be home for dinner. Money laundering and tax avoidance are reasons the Caymans have become one of the world’s largest banking centers.

Those who think that the war on drugs has been a failure have misunderstood its purpose. It has made illegal drugs more profitable making billions of dollars for those in the market; it has fueled a private prison industry in the U.S., made money for the banks and has been used to politically control nations. Was it intended to control drugs? Or, was it to make them more profitable? Follow the money!

Now under Trudeau the second, Canada is making some progress as it fumbles towards making an unregulated distribution system meet some standards of the corporate marketplace. I’m proud to have played a small part.

*

This article is based on part of chapter 3 in the book An Insider’s Memoir which is available at www.aninsidersmemoir.com or on Amazon.

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Note

[1] The Economist, Feb. 2007 http://www.economist.com/node/8695139?story_id=8695139