Canada and the First World War: Opposition to Conscription in Canada and Quebec

On the occasion of the centenary of the end of World War I, TML Weekly has been producing an excellent series of informative Supplements on the war and related matters of concern.

This is the second in the series. Click for No. 1 (How the First World War Out); N 2 (Canada and the First World War); No. 3 (British Movement of Conscientious Objectors); No. 4 (Contributions and Slaughter of Colonial Peoples in World War I); No. 5 (Steadfast Opposition to the Betrayal of the Workers’ Movement); No. 6 (Poems on the Occasion of the Centenary of the End of World War I – Moments of Quiet Reflection.

In August 1914, Britain declared war on the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Canada, as a dominion of the British Empire, was automatically bound to take part.

Robert Laird Borden, then Conservative Prime Minister of Canada, was eager to participate in the war. By Sunday, August 9, 1914, the basic orders-in-council had been proclaimed, and a war session of parliament opened just two weeks after the conflict began. Legislation was quickly passed to secure the country’s financial institutions and raise tariff duties on some high-demand consumer items. The War Measures Act 1914, giving the government extraordinary powers of coercion over Canadians, was rushed through three readings.[1]

Montreal rally in Victoria Square on May 17, 1917 was one of many opposing conscription during WWI.

Businessman William Price (of Price Brothers and Company – predecessor of Resolute Forest Products) was mandated to create a training camp at Valcartier, near Quebec City. Some 126 farms were expropriated to expand the camp’s area to 12,428 acres (50 square km). “From the start of the conflict, a range of 1,500 targets was built, including shelters, firing positions and signs, making it the largest and most successful shooting range in the world on August 22, 1914. The camp housed 33,644 men in 1914.”[2] At the time Valcartier was the largest military base in Canada.

Early in the war, Prime Minister Borden had promised not to conscript Canadians into military service.[3] However, by the summer of 1917, Canada had been at war for nearly three years. More than 130,000 Canadians belonging to the Canadian Expeditionary Force had been killed or maimed.[4] The number of volunteers continuously declined with the growing refusal to serve as cannon fodder for imperialist powers and as a result of the profound impact of the war efforts on the country’s economy. There was pressure on all the commonwealth countries and British colonies to continue providing troops for the British imperial war effort, yet the government was not able to provide a convincing argument for working people to agree to sacrifice their lives for the British Empire.

The lack of enthusiasm for the war was such that the Borden government imposed conscription through the Military Service Act August 29, 1917. It stipulated that

“All the male inhabitants of Canada, of the age of eighteen years and upwards, and under sixty, not exempt or disqualified by law, and being British subjects, shall be liable to service in the Militia: Provided that the Governor General may require all the male inhabitants of Canada, capable of bearing arms, to serve in the case of a levée en masse.”

The law was in force through the end of the war.

Borden also decided that the best way to bring about conscription was through a wartime coalition government. He offered the Liberals equal seats at the Cabinet table in exchange for their support for conscription. After months of political manoeuvring, he announced a Union Government in October, made up of loyal Conservatives, plus a handful of pro-conscription Liberals and independent members of Parliament.

Borden was in his sixth year of his first term. In the months just prior to the election he engineered two pieces of legislation, stacking the Unionist side.

Under previous laws, soldiers were excluded from voting in wartime. The new Military Voters Act allowed all 400,000 Canadian men in uniform, including those who were under age or were British-born, to vote in the coming election.

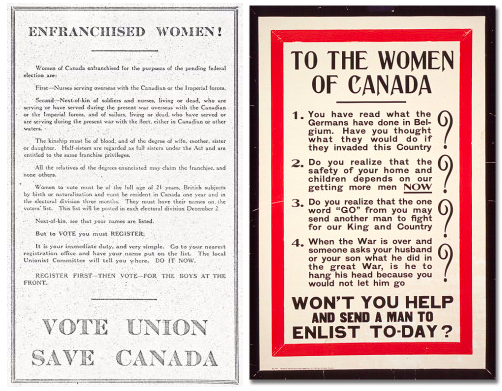

The second piece of legislation, the Wartime Elections Act, gave women the right to vote for the first time in a federal election – but only women who were the relatives of Canadian soldiers overseas. With these two laws, a vast new constituency of voters, the majority of whom supported the war effort and conscription, were suddenly enfranchised in time for the election. Borden’s Unionists won that election with a majority of 153 seats, only three of which were from Quebec.

Posters to mobilize women for imperialist war. Poster on left calls on women eligible to vote under Wartime Elections Act to vote for the Union government.

Conscription

Conscription went into effect January 1, 1918. Exemption boards were set up all over the country, before which a high percentage of men appealed their call-up for service.

Besides Quebeckers, who as a whole opposed conscription, many Canadians across the country were also opposed, including anti-imperialists, farmers, unionized workers, the unemployed, religious groups and peace activists. By February 1918, 52,000 draftees had sought exemption across the country. The lack of support for the war was reiterated by the fact that of more than 400,000 men called up for service, 380,510 appealed through the various options for exemption and appeal in the Military Service Act.

Ultimately, some 125,000 Canadians – just over a quarter of those eligible to be drafted were conscripted into the military. Of these, just over 24,000 were sent to Europe before the war’s end.

Many Canadian men simply did not show up when they were called to report and join the army. Winnipeg was second only to Montreal in the percentage of men who did not report or defaulted – almost 20 per cent of those conscripted compared to around 25 percent in Montreal, according to reports published in the Winnipeg Telegram at the time. These men were pursued by the police and could receive heavy jail sentences if caught and tried.

Opposition to the war and conscription in Quebec

Examples of the Canadian state’s clumsy Anglo-Canadian chauvinist attempts to recruit Quebeckers to its unjust cause of imperialist war, exhorting them to enlist on the basis of loyalty to the old colonial power, France; opposition to tyranny by supporting the new colonial power, Britain; or protecting themselves from foreign invasion.

On October 15, 1914, the 22nd Regiment was officially created to bolster French Canadian involvement. As the only combatant unit in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF) whose official language was French, the 22nd (French Canadian) Infantry Battalion, commonly referred to as the “Van Doos” (from vingt-deux, meaning twenty-two in French), was subject to more scrutiny than most Canadian units in the First World War. After months of training in Canada and England, the battalion finally arrived in France on September 15, 1915.[5]

In April 1916, the Van Doos participated in one of the unit’s most dangerous assignments of the entire war, the Battle of St. Eloi Craters. St. Eloi was fought on a very narrow Belgian battlefield. A fierce battle ensued with heavy casualties. Following St. Eloi, the battalion prepared to take the French village of Courcelette in the Somme sector of France. The battalion suffered hundreds of casualties. To many it showed just how violent war could really be. In the months following the Somme operations, the battalion began suffering from desertion and absence without leave. According to battalion officers, the months following Courcelette witnessed a complete breakdown in troop morale. In the next 10 months, 70 soldiers were brought before a court-martial (48 for illegal absences) and several were executed by firing squad.[6]

Despite the establishment of the Van Doos, the people of Quebec, expressing their anti-war sentiment, were at the forefront of the opposition to conscription. The Canadian establishment at the time blamed Quebeckers for the “the lack of French-Canadian participation in the war.”[7]

In Quebec, of the 3,458 individuals from the City of Hull called-up by military authorities who had not been granted an exemption, 1,902 men did not report and were never apprehended, for a total conscription evasion rate of 55 per cent. This was the highest evasion rate of all Canadian registration districts, followed closely by Quebec City at 46.6 per cent, and Montreal at 35.2 per cent. Further, 99 per cent of those called up by the City of Hull applied for an exemption, the highest application rate in all of Canada.[8]

War Measures Act Invoked

Quebeckers organized militant protests against attempts by the Canadian government to use its police powers to impose conscription on the working people and youth of Canada and Quebec. The Borden government responded by invoking the War Measures Act to quell this opposition. The government proclaimed martial law and deployed over 6,000 soldiers to Quebec City between March 28 and April 1, 1918.

On the evening of March 28, 1918, federal police raided a bowling alley and arrested the youth there. Faced with the arbitrariness and violence of the police, 3,000 people besieged the police station and continued their demonstration in the streets during the night.

Thousands of demonstrators march to Place Montcalm on March 29, 1918.

The next day, a crowd of nearly 10,000 gathered in front of the Place Montcalm auditorium (currently called Capitole de Quebec), where the conscripts’ files were administered. The military, with bayonets and cannons, were called in and shortly after the Riot Act was read, giving them permission to fire.

Within the conditions of the day, the ruling elite in Canada found a wall of resistance among the working people of Quebec to being forcibly sent to war. The aspirations of the Québécois for nationhood had been put down prior to Confederation through force of British arms. Along with the subjugation of the Indigenous peoples and the settlers in Upper Canada, the basis was laid for the establishment of an Anglo-Canadian state and Confederation. It is not hard to imagine that the Quebec working class would not look favourably on being mowed down on the battlefields of Europe in the service of the British Empire.

Notes

- “Sir Robert Laird Borden,” greatwaralbum.ca.

- “Les débuts du camp de Valcartier et d’une armée improvisée de toutes piéces,” Pierre Vennat, Le Québec et les guerres mondiales, December 17, 2011.

- Richard Foot, Election of 1917, August 12, 2015, Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Ibid.

- Maxime Dagenais, The “Van Doos” and the Great War, November 5, 2018, Canadian Encyclopedia.

- Ibid.

- “The First World War,” Sean Mills (under the direction of Brian Young, McGill University), McCord Museum website.

- Claude Harb, Le Droit et l’Outaouais pendant la Premi re Guerre mondiale, Bulletin de l’Institut Pierre Renouvin, 2017/1 (N 45), éditeur: UMR Sirice.

***

The Case of Ginger Goodwin

Twenty-four hour Vancouver General Strike was held to coincide with Ginger Goodwin’s funeral, August 2, 1918.

Ginger (Albert) Goodwin was a coal miner from England who immigrated to Canada in the early twentieth century. He worked in coal mines in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia and Michel, British Columbia before settling in Cumberland on Vancouver Island in 1910 or early 1911. He worked in the Dunsmuir coal mine in Cumberland and participated in the strike of 1912 to 1914. He was active in the United Mine Workers of America and in 1914 became an organizer for the Socialist Party.

In 1916 he moved to Trail in the interior of BC where he worked for some months as a smelterman for the Consolidated Mining and Smelting Company of Canada Limited. He was the Socialist Party of Canada’s candidate in Trail in the provincial election of 1916, coming in third, and in December of that year was elected full-time secretary of the Trail Mill and Smeltermen’s Union, a local of the International Union of Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers (IUMMSW). The following year he was elected as vice-president of the BC Federation of Labour, president of IUMMSW’s District 6 and president of the Trail Trades and Labour Council. He was proposed by the union as deputy minister of BC’s newly founded Department of Labour, but not selected. This was a proposal supported by the trades and labour councils of both Victoria and Vancouver.

Ginger Goodwin opposed World War I for political reasons on the grounds that workers should not kill each other in economic wars. “War is simply part of the process of Capitalism. Big financial interests are playing the game. They’ll reap the victory, no matter how the war ends,” he said. Nonetheless, he registered for conscription as the law required and was classified as unfit. However, not two weeks following the start of a strike in Trail for the eight-hour day, which Goodwin led, he was ordered to undergo a medical re-examination and this time was classified as fit to serve.

His appeal against conscription was rejected in April 1918. Ordered to report to army barracks he refused to compromise his conscience and hid out with others resisting conscription in the hills near Cumberland where people from the town ensured they had food and supplies.

Goodwin was shot and killed on July 27, 1918 by Constable Dan Campbell of the Dominion Police, one of three members of a team that was hunting men who were evading the Military Service Act. The anger of the people of Cumberland and workers throughout the province was such that on August 2, 1918 there was a mile-long funeral procession in Cumberland, and BC’s first general strike the same day in Vancouver.

Ginger Goodwin’s funeral, Cumberland BC, August 2, 1918.

On June 24, 2018 in honour of Ginger Goodwin, labour martyr and war resister, on the 100th anniversary of his death, the Cumberland Museum along with the BC Federation of Labour and local unions, artists, musicians and actors, re-enacted the funeral procession as part of the annual Miner’s Memorial events held from June 22 to 24. On July 23, 2018, on the occasion of the 100th anniversary of Goodwin’s death, the BC government erected a monument at nearby Union Bay, the coal port that served the Cumberland mines, in honour of Ginger Goodwin for his fight for workers’ rights and his opposition to conscription. A section of highway near Cumberland was named “Ginger Goodwin Way” in 1996 in his honour.

Recruitment of Indigenous Peoples

When the First World War broke out on July 28, 1914, Canada had no official policy on the recruitment of Indigenous peoples into the army because they did not have status as citizens. However, in 1915, as the casualties began to mount, the British government directed the Dominions to begin recruiting Indigenous people for the war effort. Australia and New Zealand, along with Canada, recruited Indigenous soldiers to fight on the side of British imperialism in the war. It is estimated that 4,000 Indigenous men and woman served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force in the First World War out of a total of some 600,000 troops from Canada. It is estimated that a third of “Status Indian” men between the ages of 18 and 45 served in the War. There are no known statistics for Métis and Inuit because the Canadian government only recognized “Status Indians” in the records.

Many First Nations, which were the main source of Indigenous recruits along with a much smaller number of Métis and Inuit, protested against the attempt to recruit them into the Canadian colonial army and opposed the arrival of recruitment officers and the Indian Agent on their reserves. Other First Nations refused to participate unless they were accorded equal status as sovereign nations and dealt with on a nation-to-nation basis by the British Crown with which they had signed their treaties.

Some Indigenous leaders and elders also reminded the government that they had received reassurances at the time of the signing of the numbered treaties with the Crown that their youth would not be serving in any wars, specially those abroad.

As well, many Indigenous women wrote to the Department of Indian Affairs demanding that the Canadian government keep its hands off their sons and husbands and that they were needed at home.

Many reasons are given for the participation of Indigenous people in the First World War. One of the reasons was the promise of a regular paycheque, another was the argument that within the First Nations, warrior societies should play their role in assisting the Crown as their relations were with the Crown, not Canada. Another argument was that after making their contributions, Indigenous relations with the Canadian state would improve when they returned.

Indigenous soldiers took part in all the major battles that the Canadian army participated in and distinguished themselves as scouts, snipers, trackers and as front line fighters winning the admiration and respect of their non-Indigenous comrades and officers. At least 50 Indigenous soldiers were decorated for bravery and heroism. In the course of the war, some 300 lost their lives and many more were wounded and others died after returning home from the effects of mustard gas poisoning, wounds that they suffered, and diseases they had contracted in Europe such as tuberculosis and influenza.

The Military Services Act passed by the the Borden Conservative government in 1917 introduced conscription including for “Status Indians.” Conscription was not only broadly opposed in Quebec, but also by Indigenous peoples who denounced this manoeuvre by the government to disregard their status as Indigenous peoples. In response to this opposition, the government was forced to grant Indigenous peoples an exemption from serving overseas.

Other injustices were also imposed on Indigenous peoples. In 1917, Arthur Meighen, Minister of the Interior as well as head of Indian Affairs, launched the “Greater Production Effort,” a program intended to increase agricultural production. As part of this scheme, reserve lands that were considered “idle” were taken over by the federal government and handed over to non-Indigenous farmers for “proper use.” After non-Indigenous and First Nations protested that this was a violation of the Indian Act, the government amended the Indian Act in 1918 to make these illegal actions legal.

Post-war brutality against Indigenous veterans

At the end of the war, returning soldiers, including Indigenous veterans, held high hopes that their contributions to the war effort would translate into a better future for themselves and their communities. Indigenous veterans thought that their status as “wards” of the state would be over and that they would be treated as equals. Instead they found that nothing changed and the racism and colonial attitudes of the Canadian government remained intact.

Many Indigenous veterans returned with illnesses such as pneumonia, tuberculosis and influenza which they had contracted overseas. Those who had suffered poison gas attacks returned with weakened lungs and became more prone to tuberculosis and other respiratory illnesses. Like their non-Indigenous fellow soldiers, Indigenous veterans suffered from the trauma of the war – which in today’s terms would be called post-traumatic stress disorder – and other illnesses such as alcoholism, which wrecked their lives and caused many problems for their families and communities. In fact, the overall standard of living in Indigenous communities declined in the years following the war as returning veterans found it extremely difficult to keep regular work and to return to their pre-war lives. In the face of these complex problems, Canada provided little support to Indigenous veterans.

Benefits and support for veterans from the Canadian government through the Soldiers Settlement Acts of 1917 and 1919, such as land and loans to encourage farming, did not extend to Indigenous veterans. To add insult to injury, through the Acts the federal government confiscated an additional 85,844 acres from reserves to provide farmland for non-Indigenous veterans.

The racist Canadian colonial state’s aim of exterminating Indigenous people by assimilating them was alive and well as expressed by the notorious Duncan Campbell Scott, architect of the Residential School System in Canada and Deputy Superintendent of the Department of Indian Affairs, who wrote in a 1919 essay:

These men who have been broadened by contact with the outside world and its affairs, who have mingled with the men of other races, and who have witnessed the many wonders and advantages of civilization, will not be content to return to their old Indian mode of life. Each one of them will be a missionary of the spirit of progress… Thus the war will have hastened that day,… when all the quaint old customs, the weird and picturesque ceremonies… shall be as obsolete as the buffalo and the tomahawk, and the last tepee of the Northern wilds give place to a model farmhouse.

The neglect of Indigenous veterans and other abuses of Indigenous peoples by the Canadian state, led Haudenosaunee veteran Frederick Loft, a Mohawk from Six Nations on the Grand River who had served as a lieutenant overseas in the Forestry Corps, to form the League of Indians of Canada in 1919. Before his return to Canada, Loft had met with the King and Privy Council in London to express his concerns about the way Indigenous peoples in Canada were being treated. Under his leadership, the League of Indians fought to protect the lands and treaty rights of Indigenous peoples.

In particular, the League fought to preserve Indigenous rights and led the battle against the “involuntary enfranchisement” changes to the Indian Act, orchestrated by Duncan Campbell Scott and passed in 1920, aimed at extinguishing Indigenous title by giving “Status Indians” the vote, while at the same time working to undermine and sabotage the work of the League of Indians and isolating and criminalizing Loft. The League also mounted legal challenges to establish Indigenous claims to hunting, fishing and trapping rights among other things.

The League of Indians was the first attempt by Canadian Indigenous peoples to form a national organization to resist the Canadian colonial state’s assault on their rights and claims and subsequently inspired the formation of other Indigenous political organizations to battle the colonial Canadian state and its racist policies.

(With files from Indian Affairs and Northern Development Canada, Canadian Encyclopedia, Veterans Affairs Canada and Library and Archives Canada.)

The Black Construction Battalion

While Blacks were used by the British colonialists as cannon fodder to suppress the struggles for rights of others, their own legitimate rights and claims were marginalized and denied.

When the First World War broke out, Blacks in Nova Scotia and other places tried to enlist but faced racist obstacles and justifications to keep them out. The Chief of the General Staff of the Canadian Army at the time asked in a memo: “Would Canadian Negroes make good fighting men? I do not think so.”

When a group of about 50 Black Canadians from Sydney, Nova Scotia, tried to enlist they were advised, “[T]his is not for you fellows. This is a white man’s war.”

In the face of repeated opposition to this state racism and discrimination, the Canadian government permitted the formation of No. 2 Construction Battalion (also known as the Black Battalion), based in Pictou, Nova Scotia. It was a segregated battalion that never saw military action because they were not permitted to carry weapons. Five hundred Black soldiers volunteered from Nova Scotia alone, representing 56 per cent of the Black Battalion. It was the only Black battalion in Canadian military history.

The Battalion was sent to eastern France armed with picks and shovels to dig ditches and construct trenches at the front, putting themselves in grave danger. They also worked on road and rail construction. Following the end of the War in 1918, the members of the Battalion were repatriated and the unit was disbanded in 1920.

According to Veterans Affairs Canada, another some 2,000 Black Canadians served in the front lines of World War I through other units, some with the armies of other countries.

Once returned, the Black veterans of the No. 2 Construction Battalion, and other returning Black veterans found that nothing had changed at home and that not only were their contributions to the war effort ignored, they continued to face racism and discrimination in employment, veterans’ benefits, and other social services.[1]

Note

1. The Canadian state likes to portray the participation of Blacks in the Canadian military in the most self-serving manner. Veterans Affairs Canada notes

“The tradition of military service by Black Canadians goes back long before Confederation. Indeed, many Black Canadians can trace their family roots to Loyalists who emigrated North in the 1780s after the American Revolutionary War. American slaves had been offered freedom and land if they agreed to fight in the British cause and thousands seized this opportunity to build a new life in British North America.”

A rosy picture, but far from reality. The slaves that sided with the British colonialists during the U.S. War of Independence, numbering some 30,000, escaped to the British side and served as soldiers, labourers and cooks. When the British were defeated, the British evacuated some 2,000 of these “Black Loyalists” to Nova Scotia with the promise of a better life and opportunities as free people. Others were thrown to the four winds landing in the Caribbean Islands, Quebec, Ontario, England and even Germany and Belgium. Those the British outright abandoned in the U.S. were recaptured as slaves.

Many of the Black Loyalists landed at Shelburne, in southeastern Nova Scotia, and later created their own community nearby in Birchtown, the largest Black settlement outside Africa at the time. Other Black Loyalists settled in various places around Nova Scotia and New Brunswick.

Far from finding freedom, and new opportunities, most of the Black Loyalists never received the land or provisions that they were promised and were forced to make their living as cheap labour – as farm hands, day labourers in the towns or as domestics. In 1791, in order to solve the “Black problem,” the British Colonial authorities repatriated about half of these Black Loyalists from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick to Sierra Leone, Africa.

Those Blacks who remained were used by the British colonial state in the War of 1812 to fight the Americans. Blacks in Ontario and also from other places were part of a colonial militia called in to suppress the Upper Canada Rebellion in 1837.

(With files from Veterans Affairs, CBC and the Canadian Encyclopedia.)

***

The War Measures Act and Internment of Canadians

Internment camp in Banff, Alberta.

Upon Great Britain’s declaration of war on Germany, the Borden Conservative government enacted the War Measures Act, in August 1914. The law’s sweeping powers allowed the government to suspend or limit civil liberties and provided it the right to incarcerate “enemy aliens.”

The term “enemy alien” referred to the citizens of states legally at war with Canada living in Canada during the war.

From 1914 to 1920, Canada interned 8,579 persons as so-called enemy aliens across the country in 24 receiving stations and internment camps. Of that number, 3,138 were classified as prisoners of war, while the others were civilians. The majority of those detained were of Ukrainian descent, targeted because Ukraine was then split between Russia (an ally) and the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an enemy of the British Empire. Some of the internees were Canadian-born and others were naturalized British subjects, although most were recent immigrants.

Most internees were young unemployed single men apprehended while trying to cross the border into the U.S. to look for jobs – attempting to leave Canada was illegal. Eighty-one women and 156 children were interned as they had decided to follow their menfolk into the only two camps that accepted families, in Vernon, BC (mainly Germans) and in Spirit Lake near Amos Quebec (mainly Ukrainians).

Internment camp in Fernie, BC.

Besides those placed in internment camps, another 80,000 “enemy aliens,” mostly Ukrainians, were forced to carry identity papers and to report regularly to local police offices. They were treated by the government as social pariahs, and many lost their jobs.

Monument to those interned at the Castle Mountain camp in Alberta.

The internment camps were often located in remote rural areas, including in Banff, Jasper, Mount Revelstoke and Yoho national parks in Western Canada. Internees had much of their wealth confiscated. Many of them were used as forced labour on large projects, including the development of Banff National Park and numerous mining and logging operations. They constructed roads, cleared land and built bridges.

Between 1916-17, during a severe shortage of farm labour, nearly all internees were paroled and placed in the custody of local farmers and paid at current wages. Other parolees were sent as paid workers to railway gangs and mines. Parolees were still required to report regularly to police authorities.

Federal and provincial governments and private concerns benefited from their labour and from the confiscation of what little wealth they had, a portion of which was left in the Bank of Canada at the end of the internment operations on June 20, 1920.

A small number of internees, including men considered to be “dangerous foreigners,” labour radicals, or particularly troublesome internees, were deported to their countries of origin after the war, largely from the Kapuskasing camp in Ontario, which was the last to be shut down.

Of those interned, 109 died of various diseases and injuries sustained in the camp, six were killed while trying to escape, and some – according to a military report – went insane or committed suicide as a result of their confinement.

Internment camp in Petawawa, Ontario. (Canadian War Museum, Calgary Herald, Wikipedia.)

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Our thanks to Tony Seeds for having brought this article to our attention.

All images in this article are from the author unless otherwise stated.