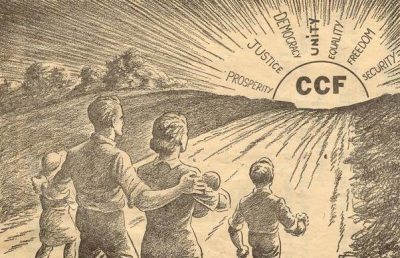

Canada and Socialism: Whatever Became of the CCF’s Dream?

A dramatic shift in electoral politics is currently disrupting leading capitalist democracies, challenging the ideological hegemony and legitimacy of the global neoliberalism of late capitalism.

In the U.S., Bernie Sanders, a self-declared democratic socialist, almost won the Democratic Party’s nomination for President. At the outset of the primaries, the nomination was widely viewed as a slam-dunk for Hillary Clinton. Some polls since the election report that Sanders may well have defeated Donald Trump.

In the UK, the Labour Party, under the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, came close to winning the election, despite the conviction of the right wing of his own party, which repeatedly tried to oust him, and the mass media, that Corbyn would lead the party to its worst defeat in history. Corbyn, a militant socialist, ran on the most left-wing platform put forward by the Labour Party since 1945.

In France, Jean-Luc Mélenchon’s La France Insoumise (rough translation: Rebellious France) missed winning a place in the run-off in the Presidential election by a few percentage points. Mélenchon was painted by the world media and the world establishment as dangerously far left.

Such events lead to an obvious question for Canadians: whatever became of the CCF’s dream?

The Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF) was founded in 1932 in Calgary, uniting various working class labour and socialist parties with populist farm organizations. In 1933, the CCF met in Regina and adopted the Regina Manifesto, concluding with a solemn pledge:

“No CCF Government will rest content until it has eradicated capitalism and put into operation the full programme of socialized planning which will lead to the establishment in Canada of the Co-operative Commonwealth.”

Co-operative Commonwealth

In 1934 the Saskatchewan Farmer-Labour Party/CCF became the Official Opposition under the leadership of George Williams. Williams served as Leader of the Opposition from 1934-1941, when he went overseas to fight fascism. Williams initiated a planning process involving the legislative caucus and key party members to prepare for power – the plan was to move quickly on the realization of socialism. Upon victory under the leadership of Tommy Douglas, the plan was largely implemented from 1944 to 1948. It was a significant step in the eradication of capitalism in Saskatchewan, involving an ambitious program of public ownership through Crown corporations, aggressive government support for the establishment of co-operatives in all economic areas, the first steps in the construction of a universal publicly funded system of social and health security, and unshackling the urban working class through unapologetically pro-labour trade union laws.

The economic cornerstone of this new socialist provincial economy was the public ownership of natural resources and their development. This was supplemented by publicly owned industrial plants to process selected resources into finished products. The CCF dream now had legs, and became a beacon of hope all across Canada.

So what became of this dream?

The short answer is the CCF’s parliamentary leadership killed it off and buried it, abandoning the visionary fight for a socialist society, where all could live in dignity and security. Instead, the leaders focused on winning elections through moderation and compromise, thus securing their careers as professional politicians seeking the ultimate prize – parliamentary power.

In 1948 Douglas led the CCF to another majority government, 31 seats of 52 with 48 per cent. The party’s 5 per cent fall in popular vote (in 1944 the CCF won 47 seats with 53 per cent), resulted in a loss of 16 seats. Douglas, the senior bureaucrats, and the cabinet panicked, convinced that a sharp right turn was necessary to retain power. The public ownership of natural resources and their development, the party’s foundational, and most controversial, socialist economic policy was abandoned. The left of the party lost its most effective champions – George Williams died in 1945 and Joe Phelps, the Minister of Natural Resources and Industrial Development, was defeated. Phelps had led the drive in public ownership from 1944 to 1948. The party establishment blocked efforts to find a seat for Phelps in a by-election, ensuring Phelps was kept out of the caucus and the cabinet.

The right turn was successfully executed. The CCF made peace with capitalism, inviting capital to lead in the development of natural resources. The publicly owned industrial plants were gradually abandoned and closed. The dream of the eradication of capitalism and building a socialist economy was unceremoniously buried.

Meanwhile, on the federal scene, M. J. Coldwell, a long time ideological opponent of Williams’ leadership in Saskatchewan, had replaced J. S. Wordsworth as national CCF leader. His primary focus in internal party politics was to ferret out and expel suspected communists, and to abandon the Regina Manifesto, which he described as a “millstone around the neck of the party.” Coldwell was finally successful in 1956 when the Winnipeg Declaration replaced the Regina Manifesto. The reborn, more right-wing and moderate CCF embraced a mixed economy and incremental steps in building the welfare state. There was no more talk of the eradication of capitalism. As far as the official party apparatus was concerned the old CCF dream was buried.

But it was a long and torturous road – the vision of socialism is hard to kill. There was resistance from the rank and file all along the way. The main problem for the leadership was that the right turn was a dismal failure, but each new leader continued the rightward march until the CCF’s successor, the New Democratic Party (NDP, founded in 1961), finally embraced neoliberalism, the latest and most savage stage of capitalism.

The NDP

This complete capitulation to capitalism finally tantalized the party under Jack Layton. The years of compromise and ideological cleansing appeared to pay off. Over four elections from 2004 to 2011 Layton led the federal NDP to significant gains in seats culminating in 2011 when the party swept Quebec, becoming the Official Opposition, one election away from power. Layton’s death in August 2011 and his replacement by Tom Mulcair set the stage for the lunge for power. In the best tradition of past party leaders, Mulcair pushed through the final compromise – rescinding the party’s commitment to apply “democratic socialist principles to government,” carefully hidden in the constitution.

The last vestige of the party’s socialist roots thus expunged, Mulcair transformed the NDP into a non-ideological government in waiting, able to provide prudent neoliberal economic leadership. In 2015 Mulcair’s NDP ran on a bold neoliberal platform: balanced budgets; debt reduction; no new taxes on the rich; and the slow realization of increased program spending over years of balanced budgets. Justin Trudeau and the Liberals pounced, campaigned from the left promising immediate deficit spending on infrastructure, job creation, and greatly enhanced program spending. Mulcair’s NDP finished third, behind the Liberals and the Tories. The party promptly drove him from office in April 2016.

This brings us to today, where the NDP’s rank-and-file membership, and its electoral base, the loyal 15 to 20 per cent, remain considerably to the left of the parliamentary leadership. No candidate in the current leadership race has provided an engaging vision for the future. In fact, the race has been greeted with yawns not only among the public, but within the party.

The dream therefore lingers on, bursting onto the historical stage at key political conjunctures. The Waffle Manifesto emerged from the new activism of the 1960s and galvanized the party in an effort to make a turn to socialism. It was defeated in 1969. In 2001 the New Politics Initiative advocated disbanding the NDP and building a more clearly socialist party with organic links with progressive social movements. Though briefly widely influential, it was defeated at the 2001 convention and disbanded in 2004. More recently, as a result of the increasingly urgent politics of the climate change crisis, and of the suffering resulting from global neoliberalism, the Leap Manifesto again galvanized the party. Its fate has yet to be determined, but the party establishment is firmly opposed. No candidate in the leadership race has tied his or her star to the manifesto.

Can the dream be resurrected for these times and move enough people to build a new vehicle for its realization? The first dream came out of the nightmares of the Great Depression and World War II, horrific disasters resulting from crises of capitalism. The dream this time must face the fact that the present stage of capitalism promises a series of worsening natural and social disasters, putting the social and natural worlds as we know them at risk – the biggest nightmare of all.

J. F. Conway teaches sociology at the University of Regina.

All images in this article are from the author.