Can an American Scientist Who Smuggled Critical Nuclear Secrets to the Russians After World War II be Considered a “Good Guy”? New Film Says Yes.

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

Controversial New Documentary Reveals How A Teenage Army Physicist Named Ted Hall Saved The Russian People From A Treacherous U.S. Sneak Attack In 1950-51—And May Well Have Prevented A Global Nuclear Holocaust

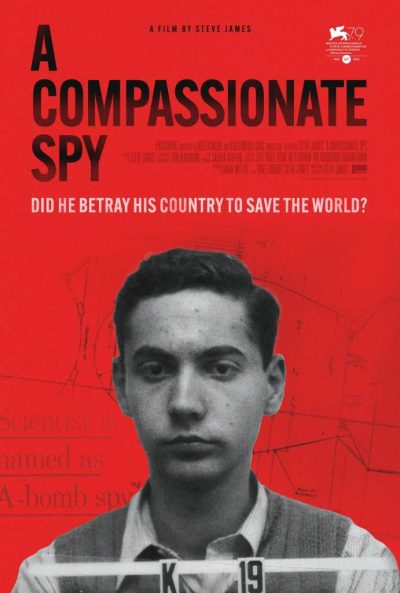

The provocative documentary “A Compassionate Spy” tells the amazing but almost unknown story of a “near-genius” Harvard physics major, who at age 17, was selected to help develop an atom bomb before the Nazis did.

At 18, after graduating from Harvard, Ted was the youngest physicist to work on the atomic bombs at Los Alamos, New Mexico. He worked with uranium and the implosion system for the plutonium bomb used in the Trinity test on July 16, 1945, one month before that bomb type killed tens of thousands of civilians at Nagasaki.

Between the bombings at Hiroshima, August 6, and Nagasaki, August 9, somewhere around 200,000 civilians were killed, and a similar number died within some months afterwards from radiation sickness and injuries.

The film also illustrates why and how Ted shared his knowledge with the Soviets: to prevent a post-war U.S. perhaps heading toward fascism and/or world domination intoxicated by having a nuclear monopoly. He foresaw correctly because, by 1946, Wall Street bankers and weapons industrialists had convinced President Harry Truman, as the film shows, to produce 400 more atomic bombs to attack the Soviet Union in 1950-51, kill millions of its people, and take over its huge land and natural resources.

Nine months after beginning work on the bomb, in October 1944, Ted received leave to celebrate his 19th birthday in New York City. It was there that he made his first contact with a Russian, Sergei Kurnakov, who was a writer and an undercover intelligence officer. Ted gave detailed plans for the plutonium bomb to the Russians, sometimes using his enthusiastic friend Saville Sax, whom he roomed with at Harvard, as courier.

In transmitting communications, the two novice spies used Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass. Ted’s Soviet spy code name was MLAD (youth).

Ted’s information corroborated what the Russians were receiving independently from scientist Klaus Fuchs. So critical was this to Soviet scientists’ ability to develop an atom bomb of their own that they made a virtual copy of the Nagasaki bomb, which was Ted’s specialty.

They exploded a test bomb on August 29, 1949, between two and five years earlier than otherwise expected by U.S. experts. According to the film, Truman was then forced to cancel his plans to pre-emptively invade Russia because retaliation by the Soviets would be likely.

(A similar dilemma was faced by President John F. Kennedy during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis when Wall Street capitalists, the Pentagon and the CIA, which was created under Truman in 1947, saw a chance to annihilate Soviet peoples in several areas. The U.S. had sought to destroy the Soviet Union ever since the Wilson administration invaded Russia following the 1918 Bolsehvik revolution. When Kennedy chose another path, a naval blockade of Cuba, it worked. The missiles were withdrawn. Yet Kennedy had also signed his death warrant).

JFK with army officials during the 1962 Cuban missile crisis. [Source: history.com]

This documentary, however, is not a political film per se. Central is the passionate, durable love story of Ted and his wife Joan, intermeshed with the history of the atomic bomb-making, its use and near-use.

Journalist and producer Dave Lindorff initiated the film idea in 2018. He, together with director Steve James and fellow producer Mark Mitten, started with three days of interviews with Joan, now 93. Joan also gave the team a video cassette which Ted, at his attorney’s suggestion, made for the “historical record.” Ted explains his reasoning for volunteering as a Soviet asset at Los Alamos.

Lindorff received the I.F. Stone “Izzy Award” for “Outstanding Independent Journalism” over his five-decade career and specifically for his exposé: “Exclusive: The Pentagon’s Massive Accounting Fraud Exposed,” The Nation, December 2018.

Steve James, two-time Academy Award nominee, was called “Chicago’s documentary poet laureate,” by The Hollywood Reporter in its September 2 review of the first film showing, which took place at the Venice Film Festival. One thousand viewers filling the Lido Hall rose to applaud for five minutes at its conclusion. A day later, the U.S. premiere was held in four full theaters at Colorado’s Telluride Film Festival.

So far, the film has been presented at six U.S. and European film festivals with at least two more to come. The funding comes from Participant Media, which is receiving bids for general distribution.

This reviewer, and my companion-photographer Jette Salling, saw the film in Cambridge where Joan and Ted lived from 1962 until his death in 1999. She still lives in the same house.

Although I am not a professional film reviewer, my six decades of peace and racial equality activism, and five decades of professional journalism lead me to the conclusion that A Compassionate Spy is both a horrendous and great film.

Horrendous because the United States of America, claiming to be the greatest democracy in the world, killed hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians in the Pacific War gratuitously.

Horrendous, all the more, because the U.S. elite and their politicians callously targeted millions more to die in the Soviet Union just as World War II was won, primarily by the USSR.

Greatest because of what two men, Ted, and Klaus Fuchs (see below) did to prevent the genocidal action. Ted Hall, and a handful of other scientists and couriers, deserve world-wide recognition by all humans who have any sense of brotherhood, sisterhood, solidarity and world peace.

One of the last public statements Ted Hall made just before he died was to encourage the next generations to demand government policies that do not put the world at such risk again.

Film Sequences

Main gate at Los Alamos. [Source: newmexico.org]

The gripping film flows smoothly, comprehensively. It opens in Cambridge, 1998, with witty, introspective and ever-feisty Joan interviewing Ted. When he arrived at remote Los Alamos, physicist Robert Oppenheimer was the scientist in charge, but the whole Manhattan Project was under the military with General Leslie Groves, a hawk, in charge. There were no sidewalks and one waded through the mud. Oppenheimer made a deal with Groves: You get your request to recruit younger scientists into the Army (less pay), and you get some streets and sidewalks paved.

Ted hated the Army and its uniform, but he had no choice.

Besides Joan, there are many interviews: her daughters; Sax’s children; the authors of Bombshell: The Secret Story of America’s Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy (1997) Joseph Albright and Marcia Kunstel; and co-author of To Win a Nuclear War: The Pentagon’s Secret War Plans Daniel Axelrod.

Actors portray the loving couple and their friend Saville in several re-enactments narrated by Joan and Ted.

In one taped interview, Ted tells Joan: The Russians were warm, helpful, charming, even funny; not authoritarian at all. They agreed on how to conduct communication, which went on for nearly two years. One method was to make codes out of passages of Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

When the Los Alamos test occurred on July 16, 1945, the allied leaders were at the Potsdam Conference: Truman, Stalin and Churchill plus Clement Attlee, who had just overwhelmingly defeated Churchill for the prime minister post. They were planning how to divide Europe post-war, and Stalin reiterated to Truman the agreement with Roosevelt at Yalta that he would send Soviet troops to help defeat Japan. That was not what Truman wanted. He planned to use the atomic bomb, in large part to prevent the Russians from sharing victory.

Ted kept to his room, away from the cheering party-makers, glad to see that their bomb worked.

Manhattan Project Scientists

Many Manhattan Project scientists did not want the bomb to be dropped on Japan, especially on civilians. When Gen. Groves told a few top scientists about that plan, one of them, Joseph Rotblat, resigned. Albert Einstein and Danish physicist-philosopher Niels Bohr, who had received the 1922 Nobel Prize for Physics, wanted FDR to share bomb information with the Soviets.

Bohr had fled Denmark early in the war upon learning that occupying Nazi forces were about to arrest him. He became part of the British component in the Manhattan Project. Bohr encouraged both Winston Churchill and Franklin D. Roosevelt to share knowledge. Churchill and Roosevelt viewed him as crazy or naïve. FDR had the FBI surveil him.

(Churchill, in fact, was soon to develop his own plan—Operation Unthinkable—formulated just after the war ended in Europe. He sought to use captured but rearmed German troops and British troops to invade Eastern Europe cities under Soviet control, and bomb three cities in the Soviet Union with Truman’s atomic bombs. Truman said they had to wait as he had only enough for Japan.)

A number of other nuclear scientists wrote a letter to President Truman asking him not to drop the bomb on civilians but to invite Japanese leaders to watch the upcoming test and thus encourage a surrender. They gave the letter to Gen. Groves, who decided not to forward it to the president.

Even the top, most hardened U.S. generals did not want the bomb dropped. They had just finished firebombing and devastating 64 cities. They knew first-hand that Japan was finished.

U.S. commander in Europe, Dwight D. Eisenhower, explained:

“Secretary of War Stimson visited my Secretary of War headquarters in Germany, [and] informed me that our government was preparing to drop an atomic bomb on Japan. I was one of those who felt that there were a number of cogent reasons to question the wisdom of such an act—dropping the bomb was completely unnecessary. I [also] thought that our country should avoid shocking world opinion by the use of a weapon whose employment was, I thought, no longer mandatory as a measure to save American lives. It was my belief that Japan was, at that very moment, seeking some way to surrender with a minimum loss of ‘face.’ The Secretary was deeply perturbed by my attitude…”

Generals Douglas MacArthur and Curtis LeMay had just bombed nearly all Japanese cities. They both held the same view as did Eisenhower. Furthermore, its use could lead to further nuclear proliferation. Nine countries now possess nuclear bombs, and some extremist terrorist jihad organizations seek them.

Despite all the protests and evidence that there was no need, Truman held fast. He claimed the bombing would save 20,000 American soldiers’ lives by not being killed in battle. We do not know how he came to that figure, but it was too low to justify the hundreds of thousands of civilians killed by the two atomic bombs. Within a few years, propaganda had fabricated a figure of one million lives saved.

Truman and other U.S. chiefs learned from their main propagandist Nazi enemy, Joseph Goebbels.

To win over the masses: Tell a lie, a big lie, repeat it everywhere over and over. You win.

As Joan says in the film: The public is not taught to think. They form opinions as told by the mass media and at schools.

Film Sequences

The shattering information about U.S. cruelty toward Japanese civilians, and its ruthless genocidal plans to decimate millions of the 193 ethnic peoples in Russia, is supported in the film by archival newsreels and declassified information, including illustrated Pentagon plans of attack.

We see that major bank owners-CEOs and weapons industrialists urged Truman to take over the Soviet Union (15 republics), in order to engorge Wall Street profits.

In contrast, war-time government propaganda and media were quite favorably inclined toward the Soviets. They were suffering many millions of deaths, and after three years of German Nazi troops and Axis ally Finnish troops occupying much of Russia and Ukraine, the Soviets were turning the tide.

Besides many favorable newsreels, Mission to Moscow is a 1943 film based on a 1941 book by the former U.S. ambassador to the Soviet Union, Joseph E. Davies. The film used clips from that government-funded Hollywood film to chronicle Davies’ experiences in the USSR, in response to Franklin D. Roosevelt who wanted the book and film made. The book sold 700,000 copies and was translated into 13 languages.

Source: imdb.com

On February 14, 1945, just three months before the end of the war in Europe, Life magazine ran a favorable cover story about the Soviet Union, how well people lived, how much they suffered under the war and how brave they were. Within a year of Life magazine’s praise, several nuclear war operations were in the works, among them Operation Dropshot. It called for making 300-400 nuclear bombs, and 29,000 highly explosive bombs to be dropped on 200 targets in 100 cities of the Soviet Union.

The War Tally

The war caused between 70 and 85 million deaths (3% of the world’s population) and untold numbers of seriously wounded. Soviet Union and China citizens accounted for half of the deaths. The Chinese lost 15-20 million, ca. 3-4% of its population. The Soviets lost 16-18 million civilians, and 9-11 million soldiers ca. 14% of its population.

A similar number were seriously wounded. It lost 70,000 villages, 1,710 towns and 4.7 million houses. Of the 15 republics comprising the Soviet Union, Russia lost 12.7% of its population: 14 million, just over half were civilians. Ukraine lost nearly seven million, over five million civilians, a total of 16.3% of its population.

The U.S. lost just 12,000 civilians, 407,300 military, i.e., 1/3 of one percent of its population. England lost just 1% of its population.

Source: Image courtesy of A Compassionate Spy

In 2015, the National Security Archive, located at George Washington University, published declassified government files revealing that, in 1956, after trashing its earlier plans to drop atomic bombs on the Soviet Union, the U.S. planned to employ the new hydrogen bomb against the populations of the USSR, Eastern Europe and China.

“Plans to target people violated international legal norms. [The Air Force Strategic Air Command] wanted a 60 Megaton bomb, equivalent to over 4,000 Hiroshima atomic weapon. Strategic Air Command Declassifies Nuclear Target List from 1950s (gwu.edu)”

What plans do they have today?

Meeting Joan

After the war, Ted enrolled in the University of Chicago to earn a doctorate in bio-physics. Then 20, he met Joan, 17, who was taking general courses at the university. Saville was also there. The three were good friends, and both men were initially in love with Joan.

One day, cuddling on a bare wooden floor, listening to Mozart, Ted asked Joan to marry him. Yes. Joan had otherwise thought she would wait to marry until she was 28 years old, but she could not resist Ted. However, he had one catch. He had to tell her what he had done with his Los Alamos work. Only Saville knew. She had to swear to secrecy. Joan listened and felt proud of him. (Her grandparents were Russian Jews.) Then, she recalled, they went back to what they were doing on the floor.

They got married, and joined the Communist Party. They viewed Chicago communists as good people, supporting Black people and unions, and world peace. Ted later pioneered important techniques in X-ray microanalysis, and kept in contact with the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs (NKVD) at their suggestion so they could get him out of the U.S. if he were to be in danger.

Ted and Joan were happy: Ted doing important work, getting graduate degrees, immersed in love.

Then the FBI came knocking.

Venona Project

The U.S. Army’s Signal Intelligence Service Venona Project (precursor to the National Security Agency) decrypted some Soviet messages. In January 1950, they uncovered two cables, one identifying Hall and Sax, and another Klaus Fuchs, as Soviet spies.

Until the encrypted documents’ public release in early 1995, nearly all of the espionage regarding the Los Alamos nuclear program was attributed to Klaus Fuchs. He had been arrested in Britain by national intelligence MI5. He caved in during interrogation to protect his sister from arrest. Fuchs served nine years of a 14-year sentence, and went to live in East Germany.

Dave Lindorff, writing in The Nation magazine on January 4, 2022, obtained, on appeal in 2021 through the Freedom of Information Act, the FBI file for Ted’s 11-year older brother Edward Nathaniel Hall. The Air Force needed to protect Ed Hall so he could continue with his rocket-making science. He was the father of the Inter-Continental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) program and Minuteman missile.

This 130-page FBI file on Ed Hall included communications between FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and the head of the Air Force Office of Special Investigations, Gen. Joseph F. Carroll, a former FBI agent. The file shows how Carroll had blocked Hoover’s intended pursuit of Ted Hall and Saville Sax, fearing that Hall’s arrest would have, in the political climate of the McCarthy era, forced the Air Force to lose their top missile expert, Ted’s brother.

Instead, the Air Force promoted Ed Hall to Lt. Colonel and later Colonel, and stopped the FBI from arresting any of them. The FBI also needed to keep the Soviets in the dark about how the U.S. had broken the Soviet encrypted code. So, the FBI settled for a one-time interrogation of Ted and Saville, in March 1951, which the two stone-walled. They tried again with Ted a few days later, but he just walked away as agents looked on. The FBI then kept a rather low-key surveillance of Ted and Joan, and Saville, which included tapping the Halls’ telephone.

The day after Ted and Saville had been interrogated, and the Air Force had asked Ed what he knew about Ted, Ed came to visit Ted and Joan. A telephone “repairman” was “fixing” their phone, which was not broken. Once the “repairman” left, Ed detected the bug.

Ed and Ted simply shared that they had been questioned. Ed did not ask if Ted had done anything. Ed died in 2006, seven years after his brother. Ed had known since Bombshell was published what Ted had done, but he never criticized him for his action.

After Ted earned his Ph.D., he and Joan believed they had to flee the FBI. Ted left the University of Chicago’s Institute for Radiobiology and Biophysics to do research in biophysics at Memorial Sloan-Kettering in New York City.

Driving to a party of Ted’s work colleagues, they passed by Sing Sing Prison where, it turned out, Ethel and Julius Rosenberg were to be executed that day. Julius had allegedly been involved in transmitting some Manhattan Project information to the Soviets, although he did not work there.

Ted later reflected with Joan that he felt remorseful. He should have turned himself in to save the Rosenbergs. Joan did not waver. The authorities, she told her husband, would simply have taken you away from me and the children, and continued the execution of Ethel and Julius. Ted knew his wife was right.

Ted and Joan had three daughters in the 1950s: Ruth, Debbie and Sara. Years later in Cambridge, Debbie died when a truck driver hit her bicycle. Joan, who became a poet and artist, read a poem in the film about Ted:

What If

What if I had died instead

and left you here behind

alone in your eighties?

How would you have lived

Would you have solved the riddle

of quantum mechanics?

Of course you’d have kept the audio

system in working order, go on

listening to your music.

Always a better housekeeper than I, you’d

have kept things much tidier. Though

come to think of it when I recall

the state of your study I sometimes wonder.

And would you have learnt to cook?

Frozen ready meals, I suppose.

But no doubt you’d have been invited

to dinner every day by one or another

of your women friends, who once

were my women friends. How would you

have remembered me? Anyway, soon

you’d surely have married again, one

of those women who loved you and envied me.

And for long years of Indian summer you

would drive along together and talk

in the car and in bed, my grey ashes melted

silently into the earth under that tall tree

in the park. Ah, now I’m jealous.

I want to be your second wife.

Their children were attending schools in Connecticut where they lived during the 1950s.

In 1962, Ted and Joan, to get away from the anti-Red hysteria in the U.S., decided to move to Cambridge University in England where Ted had been offered a research position by Vernon Ellis Cosslett’s electron microscopy research laboratory.

He created the Hall Method of continuum normalization, developed for the specific purpose of analyzing thin sections of biological tissue. Joan went to Cambridge College to learn the Russian language and its literature, and Italian. She soon taught Italian at the college, and substituted in Russian, for the next 20 years.

When some Venona files were released in 1995, Joseph Albright and Marcia Kunstel wrote Bombshell: The Secret Story of America’s Unknown Atomic Spy Conspiracy. This was the first public exposure about these whistle-blowing spies. Written in 1996, it was published in 1997.

The mass media encircled Ted and Joan’s house in Cambridge. He was maligned by the media as a traitor. Samuel T. Cohen, father of the neutron bomb, and a good friend of Ted’s at Los Alamos, turned on Ted and said in one film about atomic spying that he should be recalled to the Army, court-martialed and executed.

In a never-aired portion of the 1998 CNN-TV series “Cold War” used in the film A Compassionate Spy, Ted Hall stated:

“I decided to give atomic secrets to the Russians because it seemed to me that it was important that there should be no monopoly, which could turn one nation into a menace and turn it loose on the world as…Nazi Germany developed. There seemed to be only one answer to what one should do. The right thing to do was to act to break the American monopoly.”

Asked in another interview, what motivated him to share information, Ted pondered, and simply replied: “compassion.” Toward the end of A Compassionate Spy, Joan says, “the arms race was a farce at the expense of the American people and the world. First nuke strike was the U.S. goal.”

Ruth (l), Joan and Sara stand by Ted’s favorite tree—common beech—near their home. His ashes are buried by the tree, and Joan will lie beside him. [Source: Photo courtesy of Ron Jette Salling]

Steve James, in an interview in Cambridge following the British premiere of the film, said: “The threat of nuclear warfare remains. None of the nine nuclear powers signed the United Nations’ 2021 treaty to ban nuclear weapons.”

Only Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev had sought dismantling all nuclear weapons in the 1980s, and wanted to join NATO as partners, a proposal rejected by the Pentagon, CIA and President Ronald Reagan.

Steve James, Joan Hall, and Dave Lindorff talked at Joan’s home the day after the film showing. During end-of-film comments, Dave said Ted deserved the Nobel Peace Prize posthumously. Coincidentally, photographer Jette Salling had earlier suggested that we present a Peace Lily to Joan at the film showing.

Steve James, left, Joan Hall, center, and Dave Lindorff, right. [Source: Photo courtesy of Ron Ridenour]

Ted died November 1, 1999, of Parkinson’s disease and renal cancer. He likely acquired cancer precursor elements from the plutonium he had worked with to make the atom bomb.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Ron Ridenour is a U.S.-born author and journalist, anti-war and civil rights activist since 1961. After joining the U.S. Air Force at 17, he saw the inner workings of U.S. imperialism first hand and resigned. In the 1980s and 1990’s he worked with the Nicaraguan government and on Cuban national media. Ron can be reached at [email protected].

Featured image: Poster for A Compassionate Spy showing photo of Ted Hall. K-19 was his badge number at Los Alamos. [Source: imdb.com]