Brexit Risk: More than a Fifth of Doctors or Nurses at Some Hospitals Are from the EU

Key hospitals across England depend on the European Union for more than one in five doctors or nurses, new analysis reveals, as Brexit uncertainty deepens the NHS crisis.

Senior figures in the NHS warn they may soon not be able to fill these posts as recruitment from the EU has dried up, with knock-on effects on waiting times, operating theatre capacity and beds.

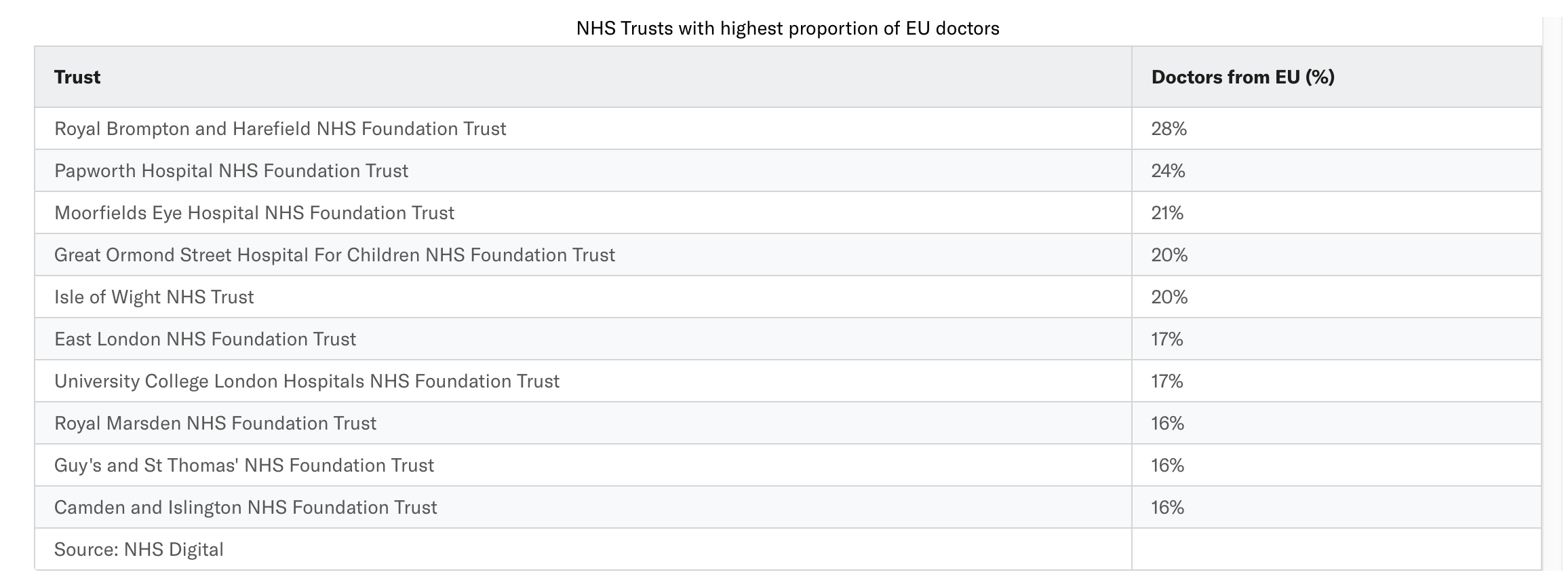

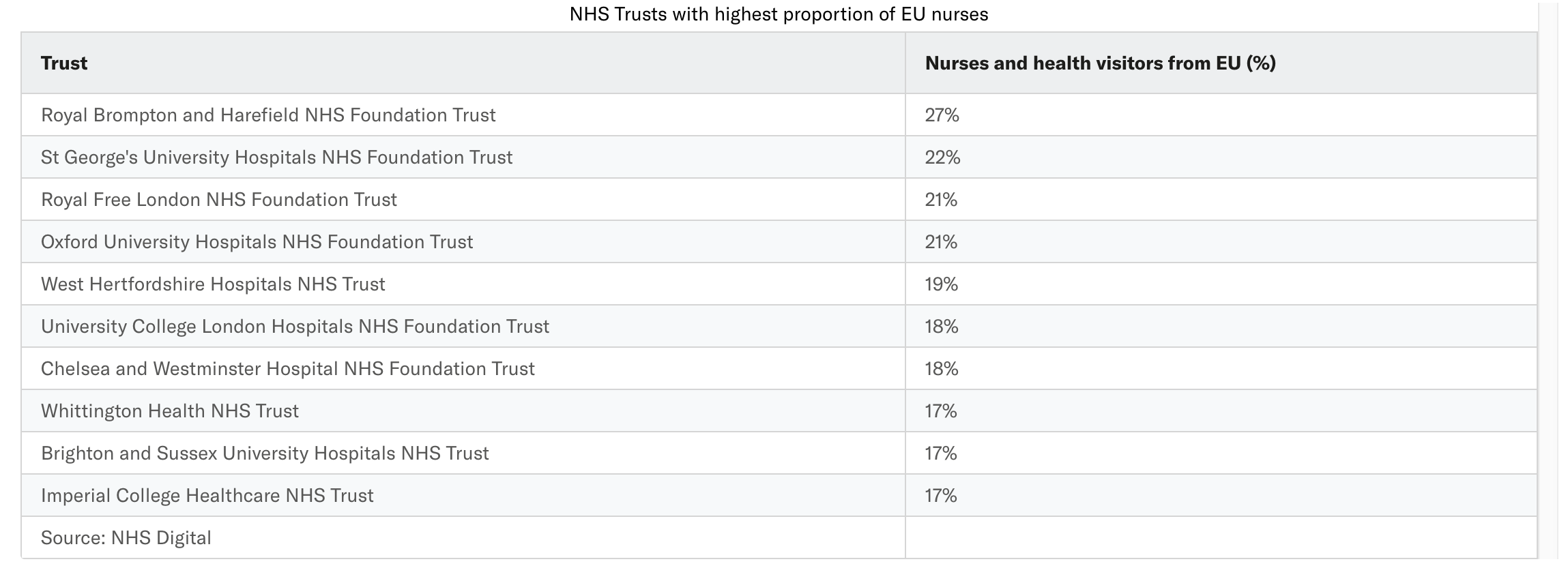

A Bureau analysis of NHS staffing shows certain trusts and specialist hospitals are heavily dependent on EU nationals, specifically for their frontline staff. Some of the most exposed include heart and lung specialists Royal Brompton and Harefield Trust and Great Ormond Street children’s hospital in London, heart specialist Royal Papworth in Cambridgeshire, Oxford University Hospitals and the Isle of Wight NHS Trust.

While across the whole of NHS England 5% of all staff are EU nationals, at eight NHS trusts they make up more than 20% of doctors or nurses. And in 92 trusts, more than 10% of doctors or nurses are from the EU.

Meanwhile recruitment from the EU has “plummeted”, said Danny Mortimer, chief executive of NHS Employers, warning that if numbers of nurses continued to fall then waiting times would go up dramatically.

“We would have to close capacity because we couldn’t man the beds or run the theatres. Costs would go up because we had to rely on agency staff and they are more expensive.”

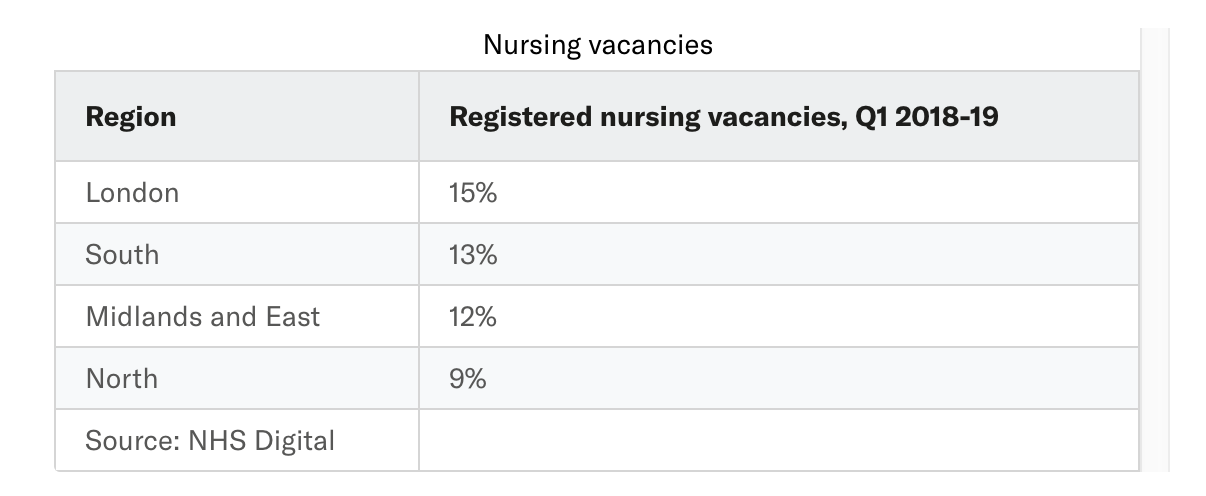

The question mark over what will happen when Britain leaves the EU has accelerated a staff crisis that was already well underway, particularly within nursing. There are now 41,000 nursing vacancies across England and annual staff turnover is more than 15%.

There is also a shortage of doctors, with 11,500 vacancies recorded in the latest figures from NHS Improvement, up from 10,800 the year before.

Brexit is just one factor impacting NHS recruitment and retention. A weak pound is making salaries much less of a draw, say analysts, and perceived anti-immigrant sentiment heightened by the Windrush scandal is also putting people off, said Mortimer.

Uneven risk

Using data from NHS Digital, the Bureau calculated the percentage of doctors, nurses and midwives from the EU at every trust in England. We focused on total staff numbers (headcount) rather than full-time equivalents.

Hospitals in London, which as a major world city has always attracted high numbers of foreign workers in the UK, topped the tables.

Royal Brompton and Harefield Trust, which runs two specialist heart and lung hospitals in the capital, has the highest proportion of both doctors and nurses. It relies on the EU for nearly a third of all its frontline staff – 28% of its doctors and 27% of its nurses are EU nationals.

Other London trusts heavily reliant on EU workers include Moorfields Eye Hospital (21% of doctors), Great Ormond Street (20% of doctors), St George’s University Hospitals (23% of nurses) and the Royal Free Foundation (21% of nurses).

London has generally been thought to be more resilient to the potential impact of Brexit, given its popularity as a destination. But its high cost of living, combined with a weaker pound, is already putting off potential EU staff, according to analysts Christie and Co. There is currently a vacancy rate in London of 9% among doctors and 15% among nurses.

“In London, the vacancy rate suggests that it is not the case to assume that ‘London will be alright’,” said Mark Dayan, policy and public affairs analyst at the health think tank the Nuffield Trust. “In that context, the reliance on EU workers looks like a liability.”

Our analysis also found various trusts outside the capital to be heavily dependent on EU frontline staff. Coupled with already high rates of staff turnover, some hospitals are struggling to replace vacancies left by EU nationals.

“This variation that’s hidden by the national picture does mean that, while certain national numbers may seem manageable – rightly or wrongly – actually, for local trusts they’re facing quite tricky challenges,” said Ben Gershlick, an analyst at the charity Health Foundation.

Oxford University Hospitals (OUH) has the highest proportion of EU nurses of any trust outside London, at 21%. And out of a total of 133 nurses who left the trust in the past year, 108 were EU nationals.

OUH did not provide a comment on the Bureau’s findings. But according to its latest annual report, turnover of staff in nursing and midwifery are among the highest in the trust.

Three out of the five trusts most dependent on EU nurses and health workers outside of London are in the East of England – West Hertfordshire Hospitals (19%), Royal Papworth Hospital (17%) and Mid Essex Hospital Services (17%).

The East of England is of particular concern as it is “an area with more rural trusts, which can make recruitment hard,” according to Nuffield’s Dayan.

West Hertfordshire Hospitals NHS Trust declined to comment. Mid Essex Hospital Services didn’t respond to multiple requests to comment.

When it comes to doctors, the trust outside London relying most heavily on the EU is Royal Papworth, a specialist heart hospital in Cambridge. We found 24% of its doctors are EU nationals. It was one of a number of specialist hospitals which had significant numbers of EU doctors, including Christie’s cancer hospital in Manchester (14%).

There is more concern about general and regional hospitals than specialist institutions, however, as it’s hoped the opportunity to work in world-renowned units will continue to attract high-calibre staff from around the world no matter what the outcome of Brexit.

A spokesperson for Royal Papworth Hospital said: “We continue to recruit proactively in the EU. Of course we are keen to know what leaving the European Union will mean for EU staff wanting to work in the UK.”

Uncertain status

Responding to the Bureau’s findings, a Department for Health (DoH) spokesperson said the number of EU nationals working in the NHS had increased since the referendum.

The DoH spokesperson said the “NHS is preparing for all situations”, but stressed that EU staff in the NHS “will be among the first to be able to secure their settled status”.

The number of EU doctors working in England has seen a small increase, rising 1.4% since 2017, but the number of EU nurses has dropped by 6%.

And in terms of recruitment of frontline staff, particularly nurses, since the referendum the NHS “absolutely has seen applications from within the EU just drop,” said Mortimer. “Like a stone.”

The government has previously said it is “publicly committed to the EU Settlement Scheme which will allow any EU citizen currently residing in the UK to register to remain here indefinitely, with broadly the same rights as now.”

The government has also talked of retaining high-skilled, high-paid workers, on salaries of over £30,000 per year, or perhaps £50,000 – there is no established policy at this time. However, given nurses earn an average of £28,000 per year in the UK, the vast majority would not meet the proposed criteria.

Mortimer from NHS Employers says hypothetical guarantees of settled status are not enough to retain staff. “Windrush has dented confidence for some of our EU colleagues,” he said. “They see a community that was given guarantees 60 years ago about their futures and they see those promises not being honoured.”

The government’s statements do not appear to have reassured EU nurses that are already in England, or those considering joining the NHS. The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) register shows new arrivals from the European Economic Area (EEA) fell by nearly 90% from 2015/16 to 2017/18, while the number leaving the register increased by a nearly a third.

Half of EEA nurses leaving the register said that “Brexit has encouraged me to consider working outside the UK,” according to the NMC.

The UK currently lets doctors and nurses from outside the EU into the UK under the Tier 2 visa system, the main visa route for skilled workers. There are caps on numbers for certain professions but doctors and nurses were given an exemption from that cap last June following campaigning by NHS organisations and medical groups.

There was alarm last week when the Home Secretary Sajid Javid said this exemption was temporary, in a letter to the Migration Advisory Committee. However the exemption is likely to continue, according to Dayan from the Nuffield Trust, “because nurses are so emotive and the shortage so bad.”

Mortimer believes anti-immigrant sentiment is putting off prospective staff from coming to work in the NHS: “Politicians have to recognise that the way in which they talk about migration isn’t just a theoretical thing, it impacts on the way people feel.”

No overnight fix

It’s less than ten months since the NHS emerged from the worst winter crisis on record. To take just one marker as an example, from December 2017 to March 2018 there were more trolley waits of more than four hours than the total amount in the same months from 2010 to 2014 combined.

On Monday, trade association NHS Providers said this winter would be even tougher. It highlighted the major role staff shortages have in driving this crisis, with a “double negative effect” – services cannot be expanded to the extent needed and existing staff are put under much greater pressure.

“Historically the UK has always relied on international recruitment to address domestic supply problems,” the report pointed out, warning that the decision to leave the EU combined with new language tests introduced in 2016 had “resulted in a significant cut to the supply line of EU workers.”

Dr Andrew Goddard, president of the Royal College of Physicians, questioned how the health service would cope with any more pressure on staffing. “With research indicating the workforce is at breaking point, anything that impacts the NHS’s ability to recruit talented, hardworking professionals is a major risk,” he said. “We know there are no overnight fixes.”

EU frontline workers were vital to the NHS’s ability to keep its services up and running, said Mortimer. “We can’t afford to lose a single colleague from the EU,” he said. “We are short across the board.”

The Bureau has been investigating the possible impacts of Brexit, to identify areas where there could be dislocation to vital sectors of the economy. One such areas is the NHS. The Bureau has no position on Brexit itself.