Brexit is Not the Will of the British People – It Never Has Been

The difference between leave and remain was 3.8 percent or 1.3 million in favour of Leave. However, in a close analysis, virtually all the polls show that the UK electorate wants to remain in the EU, and has wanted to remain since referendum day. Moreover, according to predicted demographics, the UK will want to remain in the EU for the foreseeable future.

There have been at least 13 polls since June 23rd which have asked questions similar to ‘Would you vote the same again’ or ‘Was the country right to vote for Brexit’. Eleven of these polls indicate that the majority in the UK do not want Brexit. The poll predictions leading up to the referendum narrowed but a significant majority of late polls indicated that the country wanted to remain. The leader of UKIP even conceded defeat on the night of the vote, presumably because the final polls were convincing that Remain would win.

In fact, according to the first post-referendum poll (Ipsos/Newsnight, 29th June), those who did not vote were, by a ratio of 2:1, Remain supporters. It is well known that polls affect both turnout and voting, particularly when it looks as though a particular result is a foregone conclusion. It seems, according to the post-referendum polls, that this was the case. More Remain than Leave supporters who, for whatever reason, found voting too difficult, chose the easier option not to vote, probably because they believed that Remain would win.

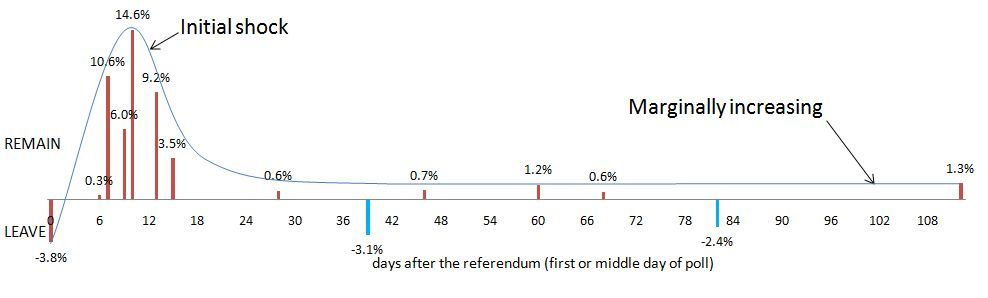

Percentage lead of LEAVE or REMAIN according to the polls post June 23rd

Immediately after the referendum, there was a marked ‘shock’ reaction in the polls against the Leave vote. Some Leave voters had voiced the opinion that they had only voted Leave to give the government a good kicking and they wished they had the opportunity to change their vote. That was reflected in the early polls with the reversal of the Brexit referendum result into double percentage figures. A higher percentage of Leave voters changed their mind to Remain, whilst the Remain voters generally stood firm. Four months on and that has now softened to 90 percent ± 2 percent of both Leave and Remain voters sticking to the guns and the rest of the original voters balancing somewhere between changing their vote or responding that they now don’t know.

What has been largely ignored are the 12.9 million who did not vote. Had the democratic process been that of Australia where voting is compulsory, the polls indicate the result would have been to Remain from day zero, and would still be Remain (see no2brexit.com and businessinsider.com). Of course, there is a criticism of the non-voter but, for various very good reasons, some were reported as simply not able to vote.

Unexpected administrative, personal or employment circumstances disabled some members of the electorate on the day from voting. One Financial Times study pointed out that most university students would generally be encouraged by their university to register to vote in their university town and they may not have realised early enough that they would have to apply for a postal vote given that term would be finished by June 23rd. The non-voters were largely younger voters and all the parties agree that the younger vote was (and still is) far more likely to vote Remain than Leave by a factor of nearly 3:1.

Since the initial shock, the gap in favour of Remain has decreased and, now, stabilised. Only two YouGov polls support a majority in favour of Leave was right, the other eleven polls have all indicated that the will of the UK is that it should remain in the EU. Such unpalatable poll results have been left unreported or occasionally inaccurately reported.

The “What would you vote now” question is being asked less frequently now. As of the middle of October, the polls indicate the continuing preference for Remain. The deciding factor is still amongst those who did not vote, with 41 percent saying that Remain was their preferred option and 26 percent preferring Leave. These figures are very similar to the News-night poll six days after referendum day when the comparative figures for the Remain and Leave non-voters were 35 percent and 19 percent respectively. When the most recent figures are applied to the 12.9 million they provide 1.9 million more Remain supporters which easily overturns the 1.3 million referendum Leave majority. Of course should there be another referendum the previous non-voters might well come out in force because they know what is at stake – but they might not.

By March 2017 when Article 50 is due to be initiated, there will be approximately 563,000 new 18-year-old voters, with approximately a similar number of deaths, the vast majority (83 percent) amongst those over 65. Assuming those who voted stick with their decision and based on the age profile of the referendum result, that, alone, year on year adds more to the Remain majority. A Financial Times model indicated that simply based on that demographic profile, by 2021 the result would be reversed and that will be the case for the foreseeable future.

Finally, two groups, in particular, saw their exclusion from the electorate as undemocratic. According to NUS polls, 75 percent of the 16-18 age group felt they should have had a vote in the UK on Brexit (given its greater long-term implications than a general election vote). The 16-18 age group did have a vote in Scotland on independence and this referendum, many felt, was at least as important. Had the younger vote come out in force there is good evidence to suggest that the referendum result would have been different.

In the second group, members of the Commonwealth (and Eire) who were resident in the UK were able to vote but other members of the EU resident in the UK were not able to vote. All EU residents of Scotland were eligible to vote in the Scottish Referendum but not in the Brexit Referendum. Clearly, if democracy is regarded as allowing those most affected by a decision to have a say in that decision, then this has not happened. With 2.9 million EU residents in the UK, it is likely that the majority would have voted for Remain and that too is likely to have reversed the decision.

Conclusion

So the UK electorate, as a whole, has been consistently against Brexit and the Remain majority will increase year on year. All things being equal Remain will be the choice of the public by the end of 2021 whether the abstaining electorate is counted or not. Those who saw the vote as a protest against poverty are now experiencing the thin end of the wedge of inflation from a falling pound and slow, drip-like movement of multinational companies out of the UK. Some Remain voters have thrown in the towel, accepting what they see as inevitable. The latest YouGov poll suggests that more people in the UK believe Brexit is bad, rather than good for jobs, will result in less influence in the world, is indifferent for the NHS, and will make the UK economy worse. A falling economy is bound to bite and reverse some of the enthusiasm for Leave and the effect of that will simply be to consolidate the trend against Brexit.

Sadly nothing less than a second, fairer referendum could redress the unfairness felt by the exclusion from the electorate of both the 16-18s and the non-UK EU residents. This all paints a very sorry picture of the effectiveness of UK democracy. Brexit is not the will of the people in the UK. It never has been. Had all the people spoken on the day the result would almost certainly be what the pollsters had predicted, and what the UK, according to the polls, still wants, and that is to Remain.

Revd. Adrian Low is Emeritus Professor of Computing Education at Staffordshire University and Church of England priest for the Costa del Sol West Chaplaincy in Spain. He is the author of Introductory Computer Vision, Imaging Techniques and Solutions.