Brazil’s “Emerging Market Economy”: Canary in “The Global Economy Coalmine”?

Chapter 3 "Emerging Markets’ Perfect Storm"

No country reflects the condition and fate of EMEs (Emerging Market Economies) better perhaps than Brazil. It’s both a major commodity and manufactured goods exporting EME. It’s also recently become a player in the oil commodity production ranks of EMEs. Its biggest trading partner is China, to which it sells commodities of all types—soybeans, iron ore, beef, oil and more. Its exports to China grew five-fold from 2002 to 2014. It is part of the five nation ‘BRICS’ group with significant south-south trading with South Africa, India, Russia, as well as China. It also trades in significant volume with Europe, as well as the US. It is an agricultural powerhouse, a resource and commodity producer of major global weight, and it receives large sums of money capital inflows from AEs.

In 2010, as the EMEs boomed, Brazil’s growth in GDP terms expanded at a 7.6% annual rate. It had a trade surplus of exports over imports of $20 billion. China may have been the source of much of Brazil’s demand, but US and EU central banks’ massive liquidity injections financed the investment and expansion of production that made possible Brazil’s increased output that it sold to China and other economies. It was China demand but US credit and Brazil debt-financed expansion as well. As in the case of virtually all the major EMEs, that began to shift around 2013-14. Both China demand began to slow and US-UK money inflows declined and began to reverse. In 2014 Brazil’s GDP had already declined to a mere 0.1%, compared to the average of 4% for the preceding four years.

In 2015 Brazil entered a recession, with GDP falling -0.7% in the first quarter and -1.9% in the second. The second half of 2015 will undoubtedly prove much worse, resulting in what the Brazilian press is already calling ‘the worst recession since the Great Depression of the 1930s’.

Capital flight has been continuing through the first seven months of 2015, averaging $5-$6 billion a month in outflow from the country. In the second half of 2014 it was even higher. The slowing of the capital outflow has been the result of Brazil sharply raising its domestic interest rates—one of the few EMEs so far having taken that drastic action—in order to attract capital or prevent its fleeing. Brazilian domestic interest rates have risen to 14.25%, among the highest of the EMEs. That choice to give priority to attract foreign investment has come at a major price, however, thrusting Brazil’s economy quickly into a deep recession.

The choice did not stop the capital outflow, just slowed it. But it did bring Brazil’s economy to a virtual halt. The outcome is a clear warning to EMEs that solutions that target soliciting foreign money capital are likely to prove disastrous. The forces pulling money capital out of the EMEs are just too large in the current situation. The liquidity is going to flow back to the AEs and there’s no stopping it. Raising rates, as Brazil has, will only deliver a solution that’s worse than the problem.

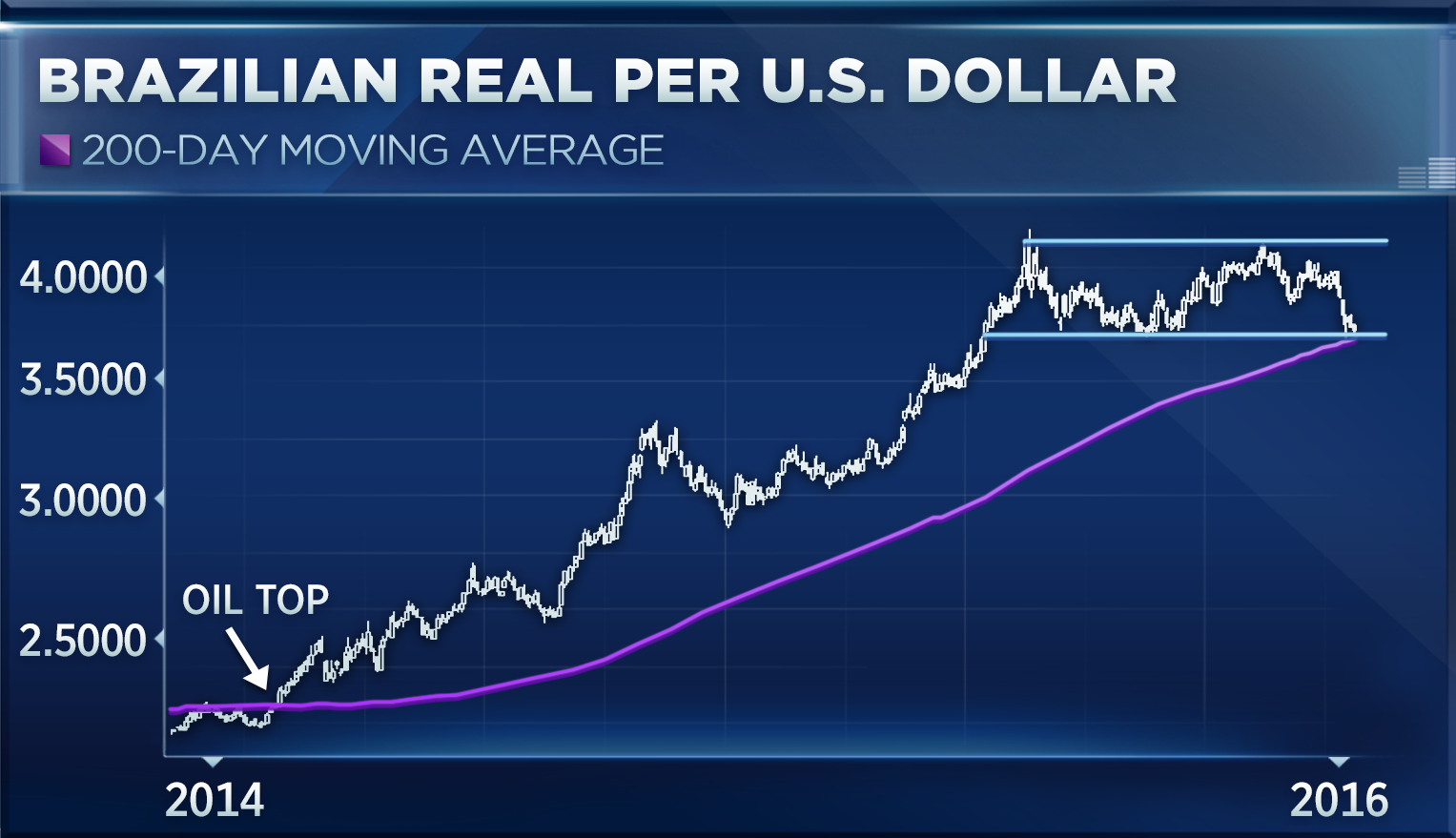

Source: CNBC

Nor did that choice to raise rates to try to slow capital outflow stop the decline in Brazil’s currency, the Real, which has fallen 37% in the past year. The currency decline of that dimension should, in theory, stimulate a country’s exports. But it hasn’t, for the various reasons previously noted: in current conditions a currency decline’s positive effects on export growth is more than offset by other negative effects associated with currency volatility and capital flight.

What the Real’s freefall of 37% has done, however, is to sharply raise import goods inflation and the general inflation rate. Brazil’s inflation remained more or less steady in the 6%-6.5% range for much of 2013 and even fell to 5.9% in January 2015, but it has accelerated in 2015 to 9.6% at last estimate.

With nearly 10% inflation thus far in 2015 and with unemployment almost doubling, from a January 4.4% to 8.3% at latest estimate for July, Brazil has become mired in a swamp of stagflation—i.e. rising unemployment and rising inflation. With more than 500,000 workers laid off in just the first half of 2015, it is not surprising that social and political unrest has been rising fast in Brazil.

The near future may be even more unstable. Like many EMEs, Brazil during the boom period borrowed the liquidity offered by the AEs bankers and investors (made available by AE central banks to their bankers at virtually zero interest) to finance the expansion. That’s both government and private sector borrowing and thus debt. Brazil’s government debt as a percent of GDP surged in just 18 months from 53% to 63%. More important, private sector debt is now 70% of GDP, up from 30% in 2003. Much of that debt is ‘junk bond’ or ‘high yield’ debt borrowed at high interest rates and is dollar denominated. That means borrowed from US investors and their shadow banks and commercial banks and therefore payable back in dollars—dollars obtainable from export sales to US customers which are slowing. An idea of the poor quality of this debt is indicated by the fact that monthly interest payments for Brazilian private sector companies is already estimated to absorb 31% of their income.

With falling income from exports, with money capital fleeing the country and becoming inaccessible, and with ever higher interest necessary to refinance the debt when it comes due—Brazil’s private sector is extremely ‘financial fragile’. How fragile may soon be determined. Reportedly Brazil’s nonfinancial corporations’ have $50 billion in bonds that need to be refinanced just next year, 2016. And with export and income declining, foreign capital increasingly unavailable, and interest rates as 14.25%–it will be interesting to see just how Brazil will get that $50 billion refinanced? If the private sector cannot roll over those debts successfully, then far worse is yet to come in 2016 as companies default on their private sector debt.

Brazil’s monetary policy response to the EME crisis of collapsing demand and exports, falling currency values, capital flight, and domestic inflation and unemployment has been to raise interest rates. Brazil’s fiscal policy response has been no less counter-productive. Its fiscal response has been to cut government spending and budgets by $25 billion—i.e. to institute an austerity policy. Like its monetary policy response of raising rates, its fiscal policy response of austerity will only slow its real economy even further.

The lessons of Brazil are the lessons of the EMEs in general, as they face a deepening crisis, a crisis that originated not in the EMEs but first in the AEs and then in China. But attempting to stop the capital flight train that has already left the station and won’t be coming back’ (to use a metaphor) will fail. So too will fail competing for exports in a race to the bottom with the AEs. Japan and Europe are intent on driving down their currencies in order to obtain a slightly higher share of the shrinking global trade pie. The EMEs do not have the currency reserves or other resources to outlast them in a tit-for-tat currency war. Instead of trying to rely on somehow reversing AE money capital flows or on exports to AE markets as the way to recovery and growth, EMEs will have to try to find a way to mutually expand their economic relationships and forge new institutions among and between themselves as a ‘new model’ of EME growth. They did not ‘break the old EME model’; it was broken for them. And they cannot restore it since the AEs have decided to abandon it.

Featured image: The Information Company