BP: The Unfinished Crimes and Plunder of Anglo-American Imperialism

In the light of British Petroleum’s grotesque crime, as yet unfinished, against humanity in the Gulf of Mexico, it is well to recall briefly BP’s no less hideous crime perpetrated in its earlier incarnation as the Anglo-Persian Oil Company (APOC) and, later, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC).

At the turn of the 20th century, William D’Arcy, financial tycoon and politician, pursuing the advice of his financial associate and empire builder Cecil Rhodes, frantically began his quest for oil in the Persian Gulf. Little did they realize that one of the most dazzling El Dorados in the long and tortured history of British imperialism would soon be born. Geopolitically it would have reverberations well beyond the Persian Gulf region. It was one of the most decisive steps in the march of imperial globalization, accelerating the concentration of capital and the imperialist rivalries that are its normal concomitant.

William D’Arcy

In 1908, D’Arcy’s quest was consummated with one of the biggest oil discoveries of all time, and APOC was established a year later. The British government would subsequently gobble up a sizeable chunk of the total shares in APOC. It was only decades later that BP was privatized by Thatcher.

In record time, Abadan in Persia became the world’s largest oil refinery. Not only did the advent of APOC herald one of the major triumphs in the struggle for global oil and the striving for ever-larger market shares, but its ascendancy blazed new horizons for a galloping imperialism in what was to become one of the world’s major strategic commodities with the onrush of the automobile age. The reverberations of the production and marketing of this commodity – earlier labelled black gold by Rockefeller – at a moment when imperialism’s first major holocaust, the Great War (1914-1918), was about to erupt revolutionized the world economy.

APOC’s ascendancy owed nothing to the free play of market forces idealized by mythmakers of economic liberalism, but to the role of Big Capital and the thrust of imperial financial power for enhanced control of world markets. Like the earlier conquests and brutal territorial annexations of Cecil Rhodes, it signallized the marriage of Big Capital and the imperial political-military complex. The pivotal actor in this compulsive planetary drive to market supremacy and control was Winston Churchill (1874-1965), soon to become First Lord of the Admiralty.

Winston Churchill

Cecil Rhodes

As with Rhodes’ earlier African conquests – from the Cape to Cairo – Churchill (a personal friend of both Rhodes and D’Arcy’s) grasped immediately the potential of APOC to alter the balance of geopolitical power in favour of British imperialism, which was then facing the life-and-death challenge of German imperialism. It proved a major catalyst in the enhancement of the global reach and unchallenged supremacy of the Royal Navy and the British merchant marine.

An El Dorado of boundless prospects opened up, and well could Churchill label it, without hyperbole, as one of the greatest pillars of the British Empire. Well before APOC came into existence, all members of the British ruling class had been big-time investors in the super-lush pickings of empire. APOC added to Churchill’s already immense personal financial spoils and not least to those of the royal family. Not only was it a prodigious source of accumulation for the entire British ruling class but it also fanned the already raging fires of inter-imperialist rivalries. Imperial Germany’s drive into the Ottoman Empire’s backyard was checkmated and pushed back. The Royal Navy successfully blockaded oil supplies to Germany when the war was unleashed.

Of crucial strategic importance was that British capitalism had largely ceased to be dependent on the world’s largest petroleum giant, the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, slated to become one of its major economic rivals. With huge British government subsidies, that is, the taxpayer’s money, APOC acquired the world’s largest tanker fleet; it came to dominate the entire oil market from pit head to the retail pump. British imperialism was to reap the benefits of its victory over its imperialist rivals in all ways and APOC was one of the vital catalysts in this battle for the conquest of world markets.

With the dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, British imperialism turned the newly emergent Iraq into a British neo-colony and the private preserve of APOC. In joint ventures with the British Burmah Oil Company, the vast oil reserves of Kirkuk were grabbed and monopolized. This colossus of British imperialism, like its contemporary American counterpart, the United Fruit Company (born in 1898), came to enshrine the rapacity of imperialist hegemony. As with UFC, its corporate existence was to be soaked in blood, political intrigue and manipulation of the highest order.

The debacle of German, Ottoman, Austro-Hungarian and Russian imperialism did not lead to the end of imperialist rivalries but rather to intensified drives for enhanced market conquests in the crisis-stricken years and decades that followed. State terrorism, not dialogue, became the exclusive instrument of imperial rule.

The year 1919 signallized a turning point in the history of APOC in Iran and indeed throughout the Middle East (yet another imperialist designation). It marked the first organized strike at the Abadan refinery. More than 30 workers were killed by the Shah’s army acting in concert with the special armed constabulary created by the company. Dozens were wounded. It was at this point that MI6, the British foreign intelligence agency, began its close working relationship with the company. Many of the strike leaders and militant workers who slipped through the gauntlet were arrested and tortured in prisons located on the premises of the oil fields. APOC had taken the leap into sustained state terrorism, as had the masters of the Colonial Office and British imperialism. The Rubicon had been crossed. But what the APOC/ MI6 duo could never have imagined were the long-term revolutionary reverberations that these well-coordinated and organized strikes would engender.

The first major strike of a colonized working class in the Middle East triggered a political firestorm that would reshape the political configuration, but of course it was not an isolated event. It was meshed into the burgeoning colonial struggles that had now become ubiquitous. The mass peasant uprising in the Mekong Delta was crushed in blood by the Foreign Legion in 1919. It was one of the largest single massacres in colonial history. More than a thousand men, women and children were killed. “The peaceful colonial world that we inherited from our parents is now exploding,” moaned British Prime Minister David Lloyd George. Of course the anti-colonial revolt and battle for freedom had begun earlier with the Easter Uprising (1916) in Ireland that was acclaimed by Lenin and throughout the colonial world.

The killings in Abadan occurred (April 1919) simultaneously with the mass murder in Jallianwala Bagh (Amritsar), India in which General Dyer’s Gurkha mercenaries slaughtered (according to the official count that was grotesquely understated) 279 non-violent Satyagrahis and left 200 gasping for life on the ground. This act of imperial butchery was, in Dyer’s arrogant words, “to teach the natives that the power of the British Empire was not to be trifled with”. But that power would be challenged not only in the Indian sub-continent but universally.

The Abadan strike had extensive political ramifications in other major cities and over-spilled into the countryside; it was the crucial catalyst in the creation of the Iranian Communist Party in 1920. Many of the leading strike militants were destined to become members of the party’s central committee. Their political mission to Moscow in that decisive year was of revolutionary significance as it blueprinted the party’s central theses, which were nationalization without compensation of the entire productive and marketing operations of APOC and its infrastructure; expropriation of the large landed estates; the democratization of the armed forces and the creation of worker/peasant militias. The struggle against APOC revealed the first fledgling roots of the party’s internationalism.

This was a revolutionary platform that left no space for reconciliation with the existing order of British imperialism and the likes of APOC. Here was a concrete example of the workings of the Third International. Many of the party’s future leaders held discussions with Lenin, Zinoviev, Bukharin and Karl Radek in which their strategies for seizure of state power were framed. The imperialist wars of intervention (1918 – 1921) against the Russian October Revolution had not yet ended when discussions with the beleaguered but soon to be triumphant Soviet leadership got underway.

Easily conceivable was that the backlash of APOC, which had already co-opted many segments of the Iranian ruling class, the army and the higher clergy with its massive payoffs, was immediate. Churchill and the masters of APOC grasped the revolutionary significance of this new politico-ideological orientation. That was not too difficult given the international revolutionary context, and the fact that foreign imperialist powers were waging a life-and-death struggle to annihilate the emergent forces of the October Revolution whose existence threatened the existing order.

The spectre of anti-communism was raised. APOC published and distributed thousands of pamphlets fulminating that the party’s blueprint for the overhaul of existing property relations would be an onslaught against Islam. It would inexorably lead, given the corollaries of their policy inferences, to the extermination of the landed aristocracy, the monarchy and private property and wholesale destruction of law and order. Such were the ideological onslaughts that would endure until the ouster of Mossadeq decades later. The party was attacked on all fronts. The incipient trade union movement was victimized but never successfully undermined, as subsequent decades revealed. The military, seeing the potential threat that the party and its freedom manifestos posed to its class privileges and prerogatives, was instrumental in imprisoning hundreds of party members and those suspected of “seditious conduct”, in the language of Reza Shah Pahlavi. State terrorism had now become a grim and present reality.

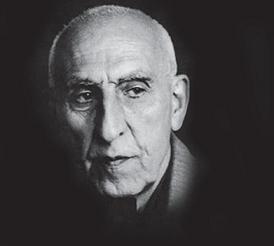

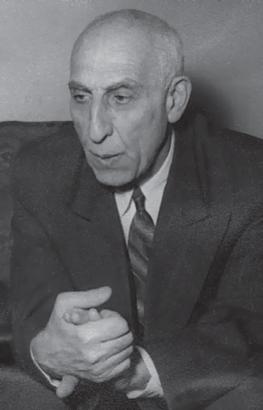

Mohammad Mossadeq (1882-1967) [1], whose active political life was galvanized at the start of the 1920s, grasped the wider meaning of the party’s programme, but recoiled from their offer of elaborating a popular front movement. It was his first strategic political blunder that he came to regret, as he would state time and again during his imprisonment after the coup and subsequent years of house arrest. This was understandable because Mossadeq was a landed aristocrat who earlier coddled the utopian illusion that APOC could be persuaded to agree to some sort of profit sharing and equitable marketing arrangement. He was what I called a reconciliationist, a believer that the sheep and the wolves could peacefully coexist. It was a perspective shared by Chile’s Salvador Allende; the upshot we all know. Let me say in parenthesis that I had a long interview with Allende a short time before his life and delusions were shattered by the bullets and the jackboots of the Pinochet/Kissinger coup.

Mohammad Mossadeq

This was proof sufficient that Mossadeq, a well-intentioned Western-educated bourgeois intellectual, had never been fully unshackled from the cultural stranglehold of imperialism (a theme that Edward Said analyzed perceptively in his chef d’oeuvre, Culture and Imperialism). As a self-styled nationalist, Mossadeq’s goal in the 1920s and early 1930s was never to effectuate changes in the social propertied relations of Iran. That was true in relation not only to the monarchy and the landed estates but also to APOC. He strenuously believed that reason could prevail and that capitalism was an economic engine susceptible to modification, that is, to becoming more humane. He failed to understand the Gandhian truth that there could be no such thing as “equality between unequals”.

The 1930s and the horrors of the Great Depression crystallized and radicalized his thinking in several ways. The visceral hatred on the part of his own social class towards his persona and his policies became clearer as the crisis deepened. As General Fazlollah Zahedi, his Interior Minister and later the hatchet man who demanded that he be hanged after the successful putsch, would say: “He was an unredeemable criminal that betrayed his class.”

The advent of Nazi-oriented parties in Iran deepened Mossadeq’s insights of the dynamics of imperialism and its domestic stooges. He had ceased to live in a cocooned world. What was important was that as an acute intellectual, a citizen of a quasi-colonial country who travelled widely within Iran, the Middle East and Europe during those years of ascendant fascism and brutal colonial repression, Mossadeq grasped the significance of the changes then shaking the colonial world and the nature of European fascism. He came to realize that fascism, despite its parliamentary and nonparliamentary variants, was a bulwark of imperialism and the racism that partnered it. His theoretical insights were soon to be metamorphosed into concrete policy directives. The Great Depression, trailed by the collapse of commodity prices and mass joblessness on a scale unprecedented in capitalism’s history, brought him closer to the resistance movements in the colonial world. India became a formative influence in his thinking and the nationalist policies that flowed from it. His encounters and lengthy exchanges with such legendary nationalist resistance leaders as Nehru, Gandhi and, above all, Krishna Menon were of decisive importance.

Mossadeq, as Menon said to me on many occasions in Bangalore, enshrined the qualities and dilemmas, and shortcomings, of many colonial intellectuals. True, Mossadeq shifted ideological gears in the crisis-strapped 1930s, but it was a radicalization or rather conversion that stopped short of hammering out a full-blooded militant working relationship with the Iranian Communist Party. (The latter renamed itself the Tudeh Party in l941.)

A crucial date in Mossadeq’s political trajectory (and that of APOC, which was renamed the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) in 1935) was the forced abdication in 1941 of Reza Shah Pahlavi, who was succeeded by his son Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. The date was of immense geopolitical significance. It coincided with the first massive Soviet offensive that pushed the Wehrmacht 200 km west of Moscow and the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour. The anti-fascist coalition gave a new impetus to the resistance struggle. Oil was being marketed to the Soviet Union for the first time despite AIOC’s stiff resistance. Tudeh’s new strategy was to resist calls for precipitous nationalization. Its central goal was to extend its organizational power base throughout the country by mobilizing the industrial working class and the peasantry, and making deep recruitment inroads into the armed forces.

Reza Shah Pahlavi

Mohammed Reza Pahlavi

This policy orientation moved in tandem with closer collaborative work with Mossadeq’s National Front. This new turn was masterfully summarized in a proclamation by Tudeh’s Central Committee. Couched in a language of moderation, it was nonetheless interpreted by the ruling class, AIOC and imperialism as signalling the liquidation of AIOC and the end of Britain’s influence:

“Our long-term goal is the building of a coherent socialist society. That means democracy, social justice, equality before the law, and elimination of repression and violence against our people. We must extend our organization in all sectors of society into every corner of our land. This marks a deepening of the democratic process. We shall work with those who honestly strive to work with us for a democratized social order. We shall continue to support the struggles of the peoples of the USSR against the fascist barbarians. We shall not act in haste so as not to jeopardize our fraternal relations with our friends and sympathizers.”

Although he would return later to Iran from his forced internment in Cyprus, the voices of the likes of General Zahedi, a paid Nazi agent and a servant of AIOC, were momentarily stilled. But he would surface again to execute his counterrevolutionary goals at the end of the war.

Of great political importance was the election of Mossadeq as Prime Minister by the Majlis, the Iranian parliament, in April 1951. The Cold War had scaled new levels of intensity, as had the anti-imperialist drive in Iran. On the first of May – and the choice of date owed nothing to chance – more than 50,000 workers, members of the armed forces, intellectuals and peasants that comprised a large contingent of women massed in front of the Majlis to give their support to the nationalization of AIOC. It was a victory that went well beyond the confines of Iran for it was the first successful manifestation of the anti-imperialist struggle.

The US-backed Syngman Rhee invasion of North Korea (June 1950) was set in motion, but it was successfully checkmated three months later by Chinese volunteers. The war in Indochina had reached a critical phase with the liberation of the frontier areas bordering China in 1949. This spelt the end of the geographical isolation of the Viet Minh freedom fighters. A frontier of 1,000 km had now been liberated. Supplies from the USSR and China would now boost the offensive capabilities of the Viet Minh in Indochina. One of his closest aides told me that Mossadeq took time to study the unfolding events in Indochina notably through his systematic study of the excellent day-by-day reports in Le Monde. His interest or, better still, ideological commitment extended to all of South-East Asia. His battle with imperialism had propelled him into the front ranks of the leadership of the anti-colonial struggle.

The nationalization decree and his non-stop daily speeches in town and country gave us a glimpse of a militant who would become one of the greatest anti-colonial speakers of his age. He was ceasing to be an armchair politico. This flight of eloquence is seen in what would become a manifesto of economic and political freedom:

“We are nationalizing the AIOC because it has systematically over several decades refused to engage in a constructive dialogue with us. Working hand in glove with the British government it has trampled on our national rights. Their conduct was one of unspeakable arrogance. Our battle for the end of the company’s domination has finally arrived and we shall triumph. It is a war against a beast that has corrupted officials at every level of the government. It has pillaged our ancient nation over decades. It has reduced us to poverty and humiliation. Above all, ours is a struggle for the conquest of our political freedom.”

The rapturous acclamation of the masses drove home to the masters of AIOC and the British Colonial Office that these were not frivolous words on the part of an opportunist politico begging for crumbs from the white man’s power structure and who believed that their conquests and pillage were things of fixity and permanence. Rather, they were a direct and powerful blow to the vitals of imperialism. Indeed, in my view, this was one of the mightiest anti-colonial manifestos that had ever been penned.

The Churchill government and Lord Beaverbrook’s tabloid yellow press in the UK unleashed their venom. Amongst other things, Mossadeq was dubbed a thieving wog, a Bazaari thug and of course a commie stooge. This sustained outpouring of filth did not stop there. The BBC joined the chorus, followed by the Voice of America. The British government engineered a series of repressive measures or, in the contemporary lingo of Hillary Clinton, “crippling sanctions” aimed at toppling the government. It warned tanker fleets that they would not receive payments from British and European banks if they marketed Iranian oil. (The loss of Iranian oil was offset by the boosted production in Saudi Arabia, Kuwait and Iraq. That was comprehensible since Saudi Arabia was a hostile enemy of Mossadeq’s reforms.)

A banking boycott by the City on Iranian credit institutions followed. The Seven Sisters, the cartel of oil corporations which controlled the world oil market, were corralled into the conspiracy to strangle the nationalization decree and bring down the government. AIOC pulled out its technicians but the workers blocked attempts to dismantle and even at times sabotage its oil installations. The British Royal Navy imposed a blockade on the entire Persian Gulf. The USSR, for reasons of its own internal policy considerations and to mollify Churchill, the United States as well as AIOC, gave no succour to Iran in its moment of dire need.

The UK took the matter to the United Nations Security Council. Mossadeq’s discourse at the Council session in October 1951 was one of the most tragic utterances of a country that was being raped and pillaged and striving to retain its dignity:

“It went without saying that as long as the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company had a monopoly over this source of national wealth, the government and people of Iran could not enjoy political independence. Despite its business façade, this company is to be considered as the modern counterpart of the old British East India Company, which in a short span of time extended its control over India. The Anglo-Iranian Oil Company had an annual income exceeding that of the Iranian government; its foreign trade was larger than ours; it intervened actively in the internal affairs of the country, and grossly interfered in our elections to the Majlis and the formation of cabinets, and thus conducting themselves in a manner calculated to wring the greatest profits from resources which it owned and controlled. By a complex conspiratorial network within the country, by widespread corruption of government ministries, and the illegal support to native journalists and politicians, it had in fact created a State within a State. Little by little it sapped the independence of the Iranian nation.” [2]

What Mossadeq has bequeathed us is a portrait of imperial genocide seen in the stricken soul of one of its most legendary victims. This damning indictment of one of the most brazen criminal corporations of all time has never, in my view, been more succinctly portrayed.

There was no respite in the offensive against the progressive and nationalist forces led by Mossadeq. The counter-revolutionary putsch was gathering steam. Churchill, who had been in the counter-revolutionary business since 1917 and whose hatred of revolutions and of coloured peoples was legendary, recognized that a bankrupt Britain was incapable on its own of pulling down the Iranian government. He pleaded with Eisenhower, who didn’t need too much urging, in the name of the US-British “special relationship”, to bring down a “monster that was threatening Western civilization”. This was a manifesto of political genocide. It left nothing unsaid.

“We are fighting a war,” he ranted on, “against a communist offensive that is moving on all fronts. The Chinese terrorists are at our throats in Malaya. They have a stranglehold of the country. Ho Chi Minh backed by the Chinese and Russian communists is fighting to grab rich Indochina. [Indonesia’s] Sukarno is a communist stooge and that land endowed with unmatchable oil and mineral and agricultural resources will be grabbed by Peking and Moscow. In Korea, the red hordes of Mao have invaded the country and they are killing Americans in great numbers. Compounding this onslaught is that a communist Russia bent on further conquests has thrown its full weight in support of the war against freedom. The moment is propitious to halt the drive to communism. For all these reasons we have to root out the tyranny of Mossadeq.”

In the corridors of imperial power in Washington the alltoo- familiar Churchillian babble, recycled for decades and distillated in the Fulton Declaration (1946), found an echo in the now militantly expansionist circles of corporate imperialism underpinned by the political/military oligarchy in the United States.

Of major historical significance, aggravating the agony of imperialism, was that yet another liberation struggle had taken root in Washington’s backyard which was, as Che Guevara said, to alter the history of the Americas, and indeed the world. In 1951 President Jacobo Arbenz (1913-1971) scored a crushing electoral victory against the entrenched forces of the Guatemalan oligarchy, the Roman Catholic hierarchy (one of the biggest landowners in all of the Americas) and its Gringo backers. One of the major planks of his agrarian reforms – “the mildest of the mild” – empowered his government to expropriate uncultivated land of the oligarchy and the multinational food companies.

The battle lines were becoming clearer. One of the biggest latifundistas (landowners) in Guatemala (and indeed in all of Central America) was the United Fruit Company headquartered in Boston. Its shares were owned by most members of Congress and the Senate, which vastly contributed to its political leverage. One of its major shareholders and political backers was John Foster Dulles (1888-1959), later Secretary of State in the Eisenhower administration that came to power in January 1953 – a year of pivotal importance, as we shall see, in the history of Iran. His brother Allen Dulles, who would play a paramount role in the butchering of Iranian democracy, became head of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). After the CIA-orchestrated eradication of the Arbenz administration in 1954, Allen Dulles became the chairman of the board of United Fruit. Indeed, the Dulles family had been among the largest stockholders of UFC since the 1920s.

John Foster Dulles

Allen Dulles

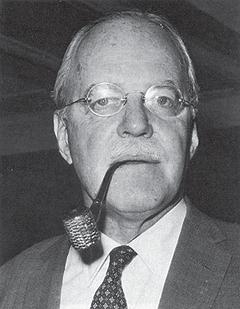

By the start of January 1953, the offensive against Iran was well underway. Operation Ajax, as it was codenamed, was engineered to axe the legitimately elected government. It would be the precursor of several such crimes against humanity in the years and decades that followed. By temperament and his unbendable ideological propensity to aggrandize the sphere of imperial conquests in the Middle East and grab its oil resources, the choice of Kermit Roosevelt Jr. (1916-2000), a long-serving CIA professional agent, to direct Operation Ajax proved ideal. A fact repeatedly acknowledged by his mentors, the Dulles brothers.

A grandson of ex-president Theodore Roosevelt, he was an entrenched conservative and a card-carrying Republican Party member. Indicative of his class outlook was his burning hatred of the New Deal and of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who he incessantly proclaimed had betrayed his class and was shovelling America down the road to communism. From this he drew the inference that the CIA was the most appropriate institution “to defend America’s interests at home and abroad”. He was a symbol of the moneyed East Coast establishment; a WASP (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) educated at Groton and Harvard. His first postings to the Middle East had reinforced his earlier connections with the tycoons of Big Oil and the Wall Street bankers – connections that he nurtured until his death. In short, his credentials for the political and human genocide that he was now to trigger were unblemished.

He slipped into Iran under the alias of James Lockridge. He had personally recruited his fellow criminal conspirators from the Iranian army and upper Shia clergy, members of MI6 with American passports and members of AIOC. One of his most ruthless co-conspirators (dubbed the Iranian Himmler by his Iranian military associates) was General Zahedi, former Minister of the Interior in Mossadeq’s cabinet. Zahedi, as an animal that had fed from many troughs, had long been on the payroll of AIOC. The rope, as an MI6 conspirator jubilantly noted, had been slung over Mossadeq’s neck but the trapdoor remained to be sprung.

General Fazlollah Zahedi

A special plane chartered by AIOC had brought the exiled Shah back from Rome. Allen Dulles was on that plane. As Zahedi later said: “The money flowed into our coffers like the Niagara Falls.” He was right in a way, but for Dulles the sum of $5 million sprinkled across the spectrum to a wholly corrupt band of gangster politicians was piddling as the gains, both financial and geo-strategic, to imperialism would subsequently run into the tens of billions. Mossadeq was arrested on 19 August 1953 and hauled before a military tribunal. Treated as a traitor and a criminal, he was tortured and kept in solitary confinement until 21 December. His prison term was subsequently extended to three years of incarceration followed by house arrest until his death in 1967. “Our job isn’t over yet,” boasted Kermit Roosevelt. “The enemy is running fast but we’re running faster. Wherever he goes we’ll hunt him down and kill him.” Once again he was on target.

What followed in Iran was nothing short of an inferno. The CIA had joined forces with Israel’s Mossad intelligence service that would go on to become one of the founders and manipulators of the Savak secret police force in Iran. It should be noted that Savak as conceived by Mossad and the CIA was a force that combined the institutional attributes of the Nazi Gestapo secret police and the SS military fighting units. Thousands were deported, butchered and disappeared. That was, however, a non-issue for the yellow corporate press. The repression bore striking similarities to Pinochet’s Chile, save that it was on a far vaster scale. The entire nation was blanketed by Savak, which became the highest-paid and most privileged thugs of the Shah’s Anglo-American-dominated empire.

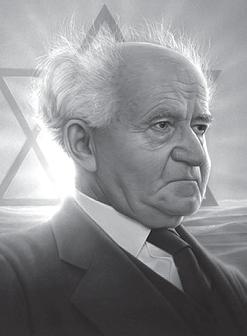

Israeli premier David Ben Gurion ecstatically proclaimed that Israel would henceforth never cease to enjoy easy access to inexhaustible and cheap supplies of oil. The oil may have been cheaper but it was now drenched with the blood of the Iranian peasant/worker resistance. The joys of Ben Gurion stemmed not only from cheaper oil but also from other, political factors. As the historical record reveals, Mossadeq and Tudeh had vigorously articulated their hostility to the mass expulsion of Palestinians from their homeland and the savage colonial occupation that followed.

David Ben Gurion

Savak became the training ground for mass murderers and torturers. Training camps were swiftly set up within Iran and in Israel as well as in that institution of mass genocide that was the School of the Americas in Panama. Genocide Inc. in Iran had now been globalized.

The pay of the Savak killers was exceptionally high. Lavish bonuses were doled out to those that denounced resistance fighters who had gone underground. The biggest and most notorious death camp, near the village of Irafshan in southern Iran, where temperatures hit 50°C in the summer months, housed 50,000 inmates at the time of the Shah’s departure. Thousands died of malnutrition, typhus and malaria.

At the University of Geneva, in Paris and elsewhere, I had the privilege of meeting several members of Mossadeq’s family and his political entourage that included members of Tudeh that had been singled out for extermination by Savak. The speed of the butchery of Iranian democracy and the horrors which trailed in its wake brought to the fore two major criminal actors in the Middle East: Iran and Israel. The Shah’s tyranny continued its march of unrelenting terror until it was ignominiously crushed in 1979.

The ousting of Iranian democracy boosted US imperial hegemony. It would ensure US imperial rule but it also marked the irreversible eclipse of British imperialism that was accentuated after the nationalization of the Suez Canal in 1967.

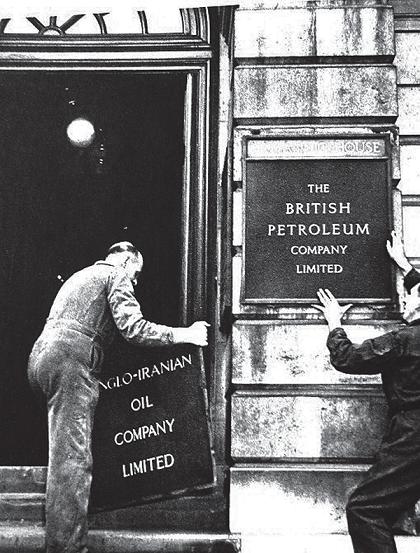

Kermit Roosevelt and his co-conspirators had saved BP’s (AIOC was renamed British Petroleum in 1954) wretched skin. In those three decades (1953-1979) BP became fully globalized, enhanced by its newly rediscovered El Dorado. Well could its stockholders enjoy their fabulous pickings. By market capitalization (1979) BP had become the world’s fifth largest company.

Kermit Roosevelt Jr.

Roosevelt had achieved the acme of his sordid career. He was the prototype of the war criminal spawned by the CIA, Mossad and MI6. The Shah’s grovelling gratitude towards these killers, including Mossad, epitomized his euphoria in the aftermath of 19 August:

“I thank God for all His mercies that he has showered on [this] Kingdom, and all of you who are gathered here for the help you have given us in eliminating the greatest scourge that our nation has ever known. I offer my special thanks to Mr Kermit Roosevelt, who has come thousands of kilometres from a land blessed by liberty, for his sustained and selfless devotion to the cause of freedom.”

It is wholly irrelevant whether the Shah was capable of drafting these lines or whether they were written by one of the foreign hangmen of the Iranian people in their embassies. But there was more to it than this fatuous piece of verbiage. Roosevelt’s colossal personal pickings were now bounteously displayed on the table for the world to see. His victims’ bodies were not among his newly acquired trophies. Among his honours were the Peacock Throne’s highest military and civilian decorations, to which was added an annual pension of $25,000 (and a lump sum of $1 million) which he received until the end of the regime in 1979.

But of course there were other delectable gifts too. BP bestowed on him an executive position on its board of directors which he turned down. What he did not decline, however, was the manna of $500,000 from the British government (the biggest shareholder in BP at the time) and BP. Overnight he metamorphosed into a big-time investor in BP, whose lush profits now rocketed to the stratosphere in the aftermath of the political coup. His destiny remained linked to the perpetuation of Big Oil.

Roosevelt went on to assume an executive position at another oil giant, Gulf Oil, and was propelled into the Political and Economic Directorate of its oil empire, which of course embraced Iran. Almost up to the end of his life (2000), this killer-conspirator never severed his connections with Iran, which he visited regularly. Nor did he shed his connections with the CIA, Mossad and his British plotters.

Roosevelt was more than a bloodthirsty mega-sized spymaster. He enshrined the unity of political power at its highest peaks and the financial exigencies of imperial aggrandizement. And hence he became a recipient of the highest award for US spies, the National Security Medal. Present at the ceremony in the White House were President Eisenhower himself, who had earlier stealthily refused to acknowledge his connections with the planned coup, the Dulles brothers, the head of MI6 and the head of BP’s operations in the Middle East. This was the grand galaxy of imperialism.

Meanwhile Mossadeq was spared the hangman’s noose because of conflicts within the conspiratorial cabal. At his death, his extensive personal papers and memoirs were confiscated and presumably destroyed. And that included his precious personal diaries. As were the CIA records of the putsch which he refused to remove. What we do know is that his overthrow did not end his militancy and what I would call his unbending faith in the unfolding revolutionary process.

Mohammad Mossadeq

He followed events intensely and, as several of my friends and informants noted, his singular regret was that he had not followed Tudeh’s injunction for arming the peasantry and the urban masses. In short, the direction of armed struggle. In the living room of his residence hung a large portrait of Ho Chi Minh which he refused to remove when ordered to do so. He followed, up to the end of his life, the liberation struggles (and repressions) in the colonial world. The triumph of Cuban freedom in January 1959 happened to be one of his greatest joys, proof of his internationalism. Even as the Iran of today and its democratically elected government face the threat of physical liquidation by the combined forces of Zionism and imperialism, the struggles and aspirations of this great humanist and architect of freedom will remain, to all who strive for justice and decency, forever green.

Notes

[1] He completed his undergraduate degree at the University of Paris and his doctorate at the University of Neuchatel.

[2] Official records of the Security Council.

Author’s note: Without the tenacity and sustained devotion of my friends Lim Jee Yuan and Lean Ka-Min, who have been a constant source of comradeship and inspiration over decades, this monograph would never have seen the light of day.

Published by Citizens International

Jalan Masjid Negeri

11600 Penang Malaysia

email: [email protected]

ISBN 978-983-3046-11-9