Bolsonaro: The First 100 Days

Near the end of the first 100 days of the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro – the first radical-right Brazilian president since the moderated transition from military dictatorship in 1985 to a democratic regime – the first meaningful protests, apart from some popular mocking and chants directed against him during Carnaval in February, took place since he assumed office on January 1st of this year.

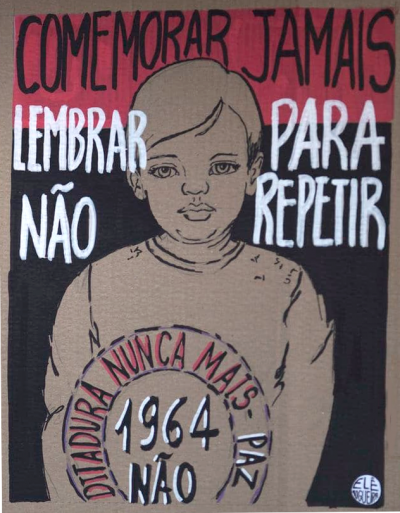

The protests were occasioned by the order Bolsonaro gave on March 25th to commemorate inside army barracks and military institutions the 55th anniversary of the Brazilian military coup of 31 March, 1964. Bolsonaro stated that he does not regard the military dictatorship as a dictatorship at all but as a regime that had ‘some problems’.

A few days later, world famous Brazilian novelist Paolo Coelho described in detail how he was tortured during the dictatorship and asked Bolsonaro if he is indeed keen on celebrating this. On the same 31st of March various cities all over Brazil saw demonstrations against this commemoration, and also smaller acts in favour of the dictatorship which led to violent scuffles in the center of Sao Paulo.

Commemorating ‘Some Problems’

An interesting footnote is that the previous commemorations of the coup by the army were only stopped by former president Dilma Rousseff in 2011. In this way, the parallel political universe maintained by the Brazilian army made itself public and official with Bolsonaro’s presidency. On the day of the latest anniversary of the coup a video, narrated by a paid actor, was sent out on the official Whatsapp channel of the presidential office, defending the coup as an emergency measure against the threat of communism.

Nobody took responsibility for the video initially. The vice-president said he didn’t know who made it, and the president’s spokesperson said he did not know who released it. Only three days later, the owner of the steel company Bendsteel, Osmar Stábile said he had financed the video, which had no imprint or logo of any official government organ. While the president himself kept silent on the issue, his vice-president later added that the president had not known about the video being sent out. Even close allies of Bolsonaro, like Joao Doria, the governor of Sao Paulo, criticized the video and said that the coup was a coup, and nothing positive.

A second protest movement had taken to the streets a day earlier on 30 March. This was a revival of the truckers’ strike of May 2018 that paralysed the economy of the country for 11 days. This time around the strike was much smaller and led only to some minor blockades in the states of Parana and Minas Gerais, similar to a slightly larger mobilization of December 2018. The fact that a new, albeit smaller, truckers’ strike took place shows that the issues behind it remain unresolved.

The truckers were seen as one of the groups backing Bolsonaro, yet neither Bolsonaro’s support for the strike in May 2018 (he changed his mind a week after endorsing the strike) nor the backing of the vast and fragmented group of truckers for the right-wing politician was firm. The central issues regard the temporary and incomplete measures taken in 2018 to alleviate the truckers’ problems and that have since ceased on 31 December. Among them are minimum freight prices and monthly instead of daily changes in the price of gasoline. These have not been renewed by the new government.

The announcement of the strike in March led Petrobras to go back to a 15-day rhythm for changing the price of gasoline. Bolsonaro’s response to the strike threat is typical of the hap-hazard measures of his style of governing. He promised in a video one day before the strike that some 8000 new planned speed radars will not go into operation, and that contracts for older speed radars will not be renewed. Thus a measure designed to enhance road security for everyone was abandoned in favour of short-term gains for truckers – whose representatives also felt dumbfounded after hearing Bolsonaro’s speech.

These two instances during the last weekend in March indicate the character of the first 100 days: a hard line regarding ideological and political issues and an unrestrained embrace of repression and violence, and the lack of any strategy to address social conflicts and political problems. The repression also took a material form with the massacre of nine youths by police in Rio de Janeiro who were fleeing from them and which was defended by the state governor of Doria. There is also the case of the killing of a musician and the wounding of others in Rio by army soldiers who fired 80 bullets into the car the musician was driving his family in; a bystander was also killed. The musician’s vehicle was probably targeted on the basis of a false suspicion. Suffice to say, the victims were members of the black majority of the population in both cases.

Similar to the government of Trump, the chaos and hap-hazard decisions are accompanied by disastrous decisions that will have a massive impact on the poor majority of Brazilian citizens. But, other than in the case of Trump, business elites are aghast at the incompetence of the president and his entourage already after three months, while his vice-president General Mourão has turned into the darling of those elites due to his supposed more reasonable actions – which tends to hide that Mourão’s political positions are not much different from Bolsonaro’s.

The main events during the first 100 days were the environmental disaster/crime at the Brumadinho dam of the Vale mining company that led to more than 300 deaths, the scandal around the corruption investigation Lava Jato (aka Operation Car Wash) and the skirmish between Bolsonaro and the president of the Brazilian parliament, Rodrigo Maia.

Corruption and Scandals

The permanent background music to those larger events are several corruption investigations and scandals involving figures close to the president. The investigations involving bank transfers by employees of Flavio Bolsonaro, a son of the president, to a middleman who was Flavio’s chauffeur, are lingering on. The former president of Bolsonaro’s Social Liberal Party (PSL) Gustavo Bebianno, an important figure, had to step down due to the high amount of public election monies that went to an unimportant candidate two days before the election. Similar investigations against the Minister of Tourism continue, and the education minister Damares faced accusations due to her adoption of a girl from an indigenous community years ago that was never officialized, and that was called kidnapping by relatives of the girl. For a supposed anti-corruption government this track record in just three months is remarkable.

What was more damaging was the scandal around the corruption investigation itself. State oil company Petrobras which is at the center of the Lava Jato scandal has also faced investigations in the USA. The indemnization that Petrobras had to pay to U.S. authorities was lowered to $853-million (all sums in U.S. dollars) in September 2018. At the time, it was reported that 20 per cent of the sum remained with U.S. authorities, and that 80 per cent, some $682-million would go to the Ministerio Público in Brazil (that led the investigations) for unspecified social and educational programs. In addition, in order to settle a class-action lawsuit it was agreed that Petrobras pay $3-billion to shareholders who bought company stocks on the NY stock exchange between 2010 and 2014. Hence, Petrobras paid almost $4-billion while, in the end a higher amount of between $5 and $10-billion had been expected by market observers.

Only in March 2019 was it revealed that the basis of this reduction was a deal between Petrobras and the U.S. authorities, signed on 26 September 2018 by representatives of Petrobras, the U.S. Department of Justice and the respective U.S. state attorneys. The deal states the sum of $682-million will go to a private NGO run by the prosecutors in the Ministerio Público of Brazil, and that Petrobras keep the U.S. Department of Justice informed about its investments and business plans.

The agreement has caused a huge uproar and led to the cancelation of plans for the NGO in question. Raquel Dodge, the supreme state attorney blocked the deal after determining it violates the Brazilian constitution, so the sum of $682-million will remain with Petrobras. Most importantly, the deal discredited the image of the investigations among the public since the suspicion was confirmed that the investigations have as one of its goals the control of Petrobras by U.S. interests, and include the direct intervention of U.S. authorities in the political life of Brazil.

The arrest of former president Michel Temer, a week after the scandal, was interpreted as a move to regain legitimacy for the corruption investigations, even if Temer had to be released after seven days. But the arrest of Temer, and other politicians, was also seen as a sign of indirect blackmail of established politicians in Congress that were about to discuss the first draft of the law for pension reform. The signal was interpreted as: ‘if you don’t organize agreement on the reform, we will also arrest you for corruption.’

While Temer was not able to pass the reform, Bolsonaro has radicalized it. Poor pensioners who today have the right to receive a pension in the value of the minimum wage from the age of 60 onward (1000 Reals, about 250 Euros), shall now receive only 400 Reals from the age of 70 onward. At the same time, the generous pensions for military personnel – who receive full salaries as pensioners and which represent the larger part of the overall budget deficit – will be largely spared.

Pension Reforms

The conflict that unfolded in the second half of March over pension reform was over Bolsonaro’s refusal to rally the deputies of Congress to support the reform draft. This is usually a game of exchanging favours, deputies negotiating in favour of their clientele, and then being rewarded with posts, money or other political favours. Bolsonaro announced that he will not distribute any favours, the practice of which he designated as the “old politics.”

Nonetheless some engagement with deputies is necessary to get the pension reform approved, and this will require several changes to the constitution if Bolsonaro sticks to the plans. It was then that the president of Congress, Rodrigo Maia from the Democratic Party, a right-wing outlet with roots in the dictatorship, began to provoke Bolsonaro in a series of tweets demanding that he “start governing” and get off of Twitter. Bolsonaro responded angrily on Twitter. Maia’s aim was to exhibit the incompetency of Bolsonaro and to bring himself into play as an important negotiator.

It was a little after this exchange of insults between Maia and Bolsonaro – Maia wrote Bolsonaro should stop “kidding around” and start working, Bolsonaro said “Maia is stressed about family issues,” alluding to the arrest of Maia’s father-in-law together with Temer – that Bolsonaro came up with his dictatorship commemoration plans, only to be topped by his Minister of Exterior, Araujo, who declared that German Nazism was a left-wing project. Bolsonaro repeated this phrase on his visit to Israel a week later, maybe the worst choice of location for it.

This incredible mess and ideological madness led to a considerable drop in the popularity of the government and Bolsonaro himself, registering the lowest poll-ratings after the first three months for any first mandate since the first elected official, Fernando Collor de Melo – even Collor who was impeached quickly, had higher approval rates. Only Cardoso and Rousseff scored worse than Bolsonaro after three months, but this was in their second mandates respectively.

The Brazilian business elite which effectively decides who stays in power once elected is getting nervous. The amateurism of Bolsonaro and his government (it would be wrong to call it a team) is seen as a danger for the pension reform and bets are now that it will be considerably watered down. Pressure groups in Congress are already calling for exceptions for firefighters, teachers and the military police. While a cut in pensions for the poor will be most disastrous, it is the middle class and reasonably paid workers in the public sector that have the most to lose with the pension cuts.

Unemployment is up to around 12 per cent, the same level as a year ago, and there is no visible economic agenda of the government. The head of the mighty agrobusiness caucus recently had cause to vent his anger against Bolsonaro. Backing away from moving the Brazilian embassy in Israel to Jerusalem, the president instead announced the opening of a commercial office in the city, while one of Bolsonaro’s sons – who regularly intervenes on political issues without coordinating with anyone – tweeted “Hamas should detonate itself” after Hamas had criticized the opening of the office in Jerusalem. A considerable amount of meat exported by Brazilian agrobusiness goes to Arab countries and is specifically produced as Halal meat in the presence of Muslim religious representatives. Other producers from India and Turkey are waiting to take over this chunk of business. Despite all the ideological regression that emanates from the Brazilian business elite, it becomes very pragmatic when its commercial interests are at stake.

It is hard to say what can be expected from the next 100 days. It is obvious that the conflict between the military faction in the government and the ideological hardliners has hardened. Moro and Guedes as the neoliberal third-pole have not shown much political leadership and independent initiative in this scenario. The hard-core making the crucial decisions are until now Augusto Heleno in the important post of national internal security leader and vice-president Mourão who demonstratively met with the Palestinian ambassador to Brazil in January – business is treating Mourão already as a president in waiting for a lack of alternatives. But the lack of coordination on the economic front is set to worsen the economic situation of the country, and it will probably be a joint protest by workers and business, albeit for different reasons, that can cause serious trouble for Bolsonaro’s motley crew.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Jörg Nowak is a political scientist at the University of Nottingham (UK) and co-editor of the magazine Rupture. His latest publications are “The Spectre of Social Democracy” in the Global Labour Journal, issue 3/2018, and Mass Strikes and Social Movements in Brazil and India (Palgrave, 2019).

Featured image is from The Bullet