Black Ops in Hollywood: From Censorship to Normalization

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram at @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

First the CIA tried to block the public from being exposed to its dirty deeds—but now the strategy has shifted to trying to normalize them.

By depicting ugly, degrading, murderous and unspeakable acts as routine, they become accepted as “the way things are done.”

Almost since the very inception of the United States, it has waged covert warfare against target nations, whether by interfering in elections, supporting opposition factions even when they are fascists, bribing government leaders and high officials and—when all of the above fails—staging coup d’états.

For most of its existence, the CIA has been the primary instrument for carrying out these particular black operations, from the Congo to Cambodia. But for a long time it did not want anyone knowing about it, even censoring books by former officers—such as Victor Marchetti’s The CIA and the Cult of Intelligence and Ralph McGehee’s Deadly Deceits: My 25 Years in the CIA—to remove details of the Agency’s special activities.

The Pentagon has also been deployed as a covert weapon, with figures like Ed Lansdale turning up on both sides of the CIA/DOD divide. Lansdale first helped put down the Marxist Huk rebellion in the Philippines while working for the U.S. Air Force, before hooking up with the CIA in Vietnam and later becoming involved in anti-Cuba operations, including the notorious Operation Northwoods.

An almost totally unrecognized aspect of covert U.S. policy is the role Hollywood has played in propagandizing the U.S. and global public—first to protect the CIA and Department of Defense (DoD) and their black operations, and more recently to promote them. For decades these agencies have worked hand-in-glove with filmmakers to manipulate not only their own public images, but perceptions of America’s role in the world.

Animals from The Farm

Back in the 1950s, when the CIA was interfering everywhere, from Guatemala to Indonesia to Syria, Hollywood helped shield the Agency from the limelight. The Production Code Administration (PCA)—the movie industry’s own self-regulation office—helped keep the CIA’s name out of numerous films. When this failed, the CIA stepped in, removing any references to it from scripts, such as in the Bob Hope comedy My Favorite Spy (1951).

Source: imdb.com

While the Agency, with Hollywood’s help, was staying out of public view, it was subtly promoting the idea of rebellions and coups against left-wing governments.

The 1954 animated adaptation of George Orwell’s Animal Farm was secretly sponsored by the CIA, which bought the rights from Orwell’s widow before hiring a British production company to produce the film.

Originally published in 1945, Orwell’s book told the story of a group of farm animals who rebel against their human farmer, hoping to create a society where the animals can be equal, free and happy. Ultimately, the rebellion is betrayed, and the farm ends up in a state as bad as it was before, under the dictatorship of a pig named Napoleon.

As recounted in Frances Stonor Saunders’ book The Cultural Cold War, the CIA’s oversight led to a crucial change in the script in the film version. The core problem was that at the end of the story it is revealed that the authoritarianism of both the men (the capitalists) and the pigs (the Soviets) is equally corrupt, and that neither offered a way forward for workers and ordinary people.

As Orwell wrote, “the creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.” However, in the CIA-influenced cartoon version, for popular consumption, the ending was changed so it shows the creatures only recognizing the corruption of the pigs, i.e., the Soviets, and then mounting a counter-revolution against them. This pro-revolutionary message—but only when the revolution deposes or fights against a left-wing government—was the first salvo in a battle that has since grown into all-out cultural warfare.

Source: upload.wikimedia.org

Scorpions and Man-Eating Sharks

After the debacle at the Bay of Pigs the CIA could no longer maintain its secret status, and the PCA’s stranglehold over movie content was weakening. This led to the Agency being openly named and discussed in movie scripts, so it started quietly monitoring screenplays for any references to itself.

For example, when it came to Vanished—the first-ever TV mini-series, from 1971—the CIA kept close tabs on the production as well as responses from reviewers. Months before it was broadcast, a memo from the CIA’s General Counsel to then-Director Richard Helms contains a review of the script. It notes how the DCI was referred to in a scene set in the Oval Office, where the President says, “Don’t let that surface charm fool you. He’s a man-eating shark. Of course, he’s our man-eating shark and thoroughly dedicated to his job.”

The CIA did not intervene to try to have this line changed—it appears in the broadcast version—so we can only assume that being characterized as a loyal, dedicated man-eating shark was acceptable to the Agency.

This same dark image of the CIA also features in Scorpio two years later, in which the Agency tries to kill one of its own due to fear of him exposing secrets. Scorpio was so beloved by the CIA that it became the first film to be allowed access to shoot at the Agency’s Langley headquarters, and officials even made up a batch of scorpion badges to hand out to the crew when they arrived. According to director Michael Winner in his autobiography, a “nice CIA lady” who was handing out the badges told him “This will show we’ve got a sense of humor, Mr. Winner!”

Post-Church Committee

However, then came the Church Committee and the revelations that the CIA was staging coups and assassinating people at will, with apparently no oversight. The CIA set up an Office of Public Affairs in the late 1970s to help manage its public image, but essentially withdrew from the entertainment industry until the early 1990s.

In the late ’70s and ’80s, several efforts were made to produce a CIA-themed TV show in the manner of the long-running ABC series The F.B.I., including one backed by the Association of Former Intelligence Officers, but they all died due to a lack of interest from the Agency.

Scene from ABC’s long-running The F.B.I. series after which the CIA wanted to model its own. [Source: thefbiepisodeguide.wordpress.com]

Likewise, when the Reagan White House’s Hollywood liaison Joe Holmes reached out to then-Director of Central Intelligence (DCI) Bill Casey about supporting an unnamed movie production, the request was also turned down.

A note from CIA Executive Director John McMahon to Casey urged him to reject the request and “keep to the reduced silhouette path.” Casey agreed, and his handwritten note says “James Bond is my favorite anyway.”

The upshot of this is that, while the CIA was conducting two of the largest covert operations of all time—Iran-Contra and Operation Cyclone—it was largely absent from pop culture. Casey’s policy of trying to reinstitute the secrecy the Agency had enjoyed in its early years was working, at least as far as Hollywood was concerned.

Patriot Games and Mission Impossible

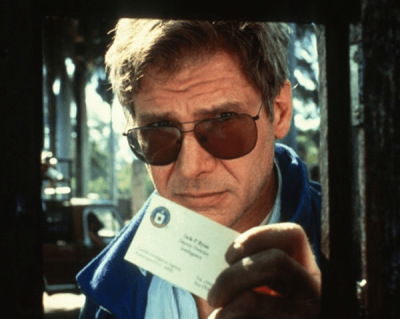

Then, things started to shift. In 1991 the CIA granted permission for the makers of the Tom Clancy adaptation Patriot Games to shoot at Langley. The film focused on the exploits of CIA analyst Jack Ryan (played by Harrison Ford) who helps capture Irish Republican Army (IRA) terrorists.

Subsequently, the CIA set up its own entertainment liaison office modeled on the equivalents at the Pentagon and the FBI. The first major production it worked on was Mission: Impossible (1996), which was filmed at Langley, and where a dialogue was altered at the CIA’s urging in order to denigrate the Church Committee for allegedly trying to destroy the Agency.

Source: imdb.com

During an insert shot where a senator is being interviewed about the CIA on TV, the script originally had the senator saying,

“I’ll go you one further. I say the CIA and all its shadow organizations have become irrelevant at best and unconstitutional at worst. It’s time we throw a little light on the whole concept of the Pentagon’s ‘black budget.’ These covert agency subgroups have confidential funding, they report to no one—who are these people?! We were living in a democracy the last time I checked.”

This scene was diluted to remove these lines, and in the finished film the insert shot instead has the interviewer say, “Senator, it sounds as if you want to lead the kind of charge – that Senator Church led in the 70’s, and destroy the U.S.’ intelligence capability.” The senator simply responds, “I want to know who they are and how they’re spending the taxpayers’ money. We were living in a democracy the last time I checked.”

Instead of the dialogue being a pointed critique of the CIA and Pentagon’s secret, black operations, it became a dig at the Church Committee, denoting anyone who tries to provide oversight of the CIA as a threat to the nation.

The Pentagon Censors Black Operations in Hollywood Scripts

The Pentagon has also shaped and censored movies to cover up for black operations it would rather the public at large not know about. A database on its work with Hollywood shows how the CIA rejected Seven Days in May (1962), “in light of story of the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff planning a coup because the president signed a disarmament treaty.” A few years later, the CIA pushed John Wayne’s The Green Berets (1968) to delete references to over-the-border raids into Laos.

Other films were not so lucky. In 1986 the producers of The Best Ranger approached the DOD for help, but were turned down “because the U.S. military becomes involved in a fictional military attempt on President Aquino’s life and a take-over of the government of the republic of the Philippines.” The film was never made.

Similarly, Counter Measures—a high-cast movie from the 1990s about a weapons-smuggling conspiracy on board a U.S. aircraft carrier—was turned down because the DOD saw “no reason to denigrate the White House or remind the public of the Iran-Contra affair.” It too was never made.

Iron Man to the Rescue in Afghanistan

Since the turn of the 21st century and the arrival of the information age, the strategy appears to have changed. These days it is easy enough for anyone to simply search “CIA coup d’états” and find no end of open-source material, even Agency documents describing in detail how, for example, it used false-flag “sham bombings” during the coup in Iran in 1953.

This shifting of the outer limits of public knowledge means that simply denying that these sorts of operations take place is no longer a viable option, and so censoring them out of movie and TV scripts accomplishes very little. Instead, the CIA and DOD have switched gears and are now trying to normalize these actions, even using superhero movies to try to make them seem cool.

Iron Man (2008) got the ball rolling. An early script shows that the intention was to make a film castigating the military-industrial complex, with Tony rebelling against his father, a major weapons manufacturer. This version was due to go into production in 2005, but the project died before being resurrected as a vehicle to launch Marvel’s Cinematic Universe.

While the original script removed Tony’s Vietnam-era origin story—where he is kidnapped by Vietnamese soldiers and forced to make weapons for them—the newly updated version, with full Pentagon support, simply updated this to Afghanistan. Tony is shown in his full military-industrial glory demonstrating incredibly destructive weapons.

When Tony is kidnapped, the terrorist leader shows off his vast collection of modern weaponry, leading Tony to ask where he got them from. As the film’s director Jon Favreau admitted during an unofficial live commentary for the movie, the leader’s response was “Carter, Reagan, Bush, Clinton, Bush”—a reference to how U.S. foreign policy had resulted in vast quantities of weapons flooding into the region over recent decades. This was removed from the film.

With lines like this nixed from the movie, Iron Man spends most of the second act of the film acting as a hi-tech adjunct to the U.S. military, conducting violent covert operations in Afghanistan while being answerable to no-one. The implication is that being American and having access to high technologies gives one extra-legal rights to do almost anything.

At the same time as Iron Man was filming scenes at Edwards Air Force Base, the actual U.S. military’s Task Force 373 was in action in Afghanistan. In June 2007, armed with HIMARS—High Mobility Rocket Systems, not unlike those on the Iron Man set—they set out to assassinate Abu Laith al-Libi. They killed thirteen people—six that they claim were Taliban fighters, and seven innocent children.

The Suicide Squad Invades Latin America

The most recent collaboration between the Pentagon and the superhero genre was James Gunn’s The Suicide Squad (2021). The original screenwriter, Adam Cozad, went on an Air Force-arranged tour of U.S. Space Command in the summer of 2017.

Source: medium.com

Once Cozad was replaced by Gunn he wrote a new script and, as soon as it was completed, the DOD “began a conversation with Warner Brothers Studios exploring possible DOD support of an upcoming feature film, a sequel to the 2016 film ‘Suicide Squad.’” Documents from the Pentagon’s entertainment liaison office show that “Producers request the use of CV-22 aircraft. General script notes have been provided to the producers.”

The CV-22 (also known as ‘the Transformer’ as it converts from a helicopter into a plane in mid-air) appears a few minutes into the film. It flies several small-time superheroes into the fictional Latin American nation of Corto Maltese where they are trying to overthrow the new government, which is considered a threat to U.S. interests. The backstory, as explained in The Suicide Squad, is that the previous government was a dictatorship but was U.S.-friendly, whereas the new government is not.

CV-22 featured in The Suicide Squad (2021). [Source: spyculture.com]

Combined with the first main action sequence—an amphibious assault whereby the low-grade superhero team is ambushed by Corto Maltese government forces—this storyline is clearly drawn from U.S. relations with Cuba.

A right-wing, U.S.-friendly dictator was deposed during the Cuban revolution and replaced by a more radical, left-wing government. The U.S. then set about destabilizing and trying to overthrow that government and assassinate its leader, including a failed amphibious assault at the Bay of Pigs.

In The Suicide Squad, the Corto Maltese radicals overthrow the government in bloody fashion—machine-gunning a room full of high officials and military brass—before appearing on TV talking about free and fair elections. Gunn’s film does not just promote this sort of covert action by the U.S., it rubs the audience’s faces in the great lie that the U.S. does these things in furtherance of democracy.

Scene from The Suicide Squad (2021). [Source: denofgeek.com]

Interrogating The Interview

Yet another government-supported production that promotes U.S. covert interventions is The Interview (2014), a comedy in part inspired by Dennis Rodman’s visit to North Korea in 2013. The story revolves around two TV stars who are invited to North Korea to interview Kim Jong-un, and are subsequently recruited by the CIA to attempt an assassination of Kim.

You could be forgiven for suspecting that a story about the CIA working with the entertainment industry in a covert capacity was quietly supported and encouraged by the CIA.

In an interview the writer/producer and star Seth Rogen said, “We made relationships with certain people who work in the government as consultants, who I’m convinced are in the CIA.” He elaborated, explaining that, when Kim disappeared for a week, he emailed one of the consultants who reassured him that Kim was having ankle surgery and “would be back in a couple of weeks.” Sure enough, Kim was back in the public eye two weeks later.

The North Korean government labeled the film an “act of war” and Sony Pictures, which had produced it, was hacked and thousands of internal documents were leaked online. These showed that senior Sony executives had discussed the film with the State Department, even showing it cuts of the movie.

Furthermore, according to leaked emails, during a press “visit the set” event, someone let slip that a “former CIA agent and someone who used to work for Hillary Clinton looked at the script.” One email exchange between executives Marisa Liston and Keith Weaver highlights concerns about this slip, but as Weaver put it, “Depending on how this comes up, this can go in any number of directions in terms of how it’s interpreted.”

Concerned about the film’s potential political impact, producers Rogen and Evan Goldberg reached out to Rich Klein of McLarty Media, to whom internal CIA documents refer as a “long time contact” of Langley’s Office of Public Affairs.

Months later, on the day before The Interview was released, Klein wrote an editorial in support of the film, calling it a “subversive and damn funny movie” and suggesting that, “if copies are pirated into North Korea, it is a very real challenge to the ruling regime’s legitimacy.”

Klein’s prediction proved prophetic: A few months after the film was released, South Korean activists started sending huge numbers of balloons into North Korea carrying tens of thousands of USB sticks and DVDs containing copies of The Interview.

This was before the film was available on DVD in many countries (including the UK), but none of the media coverage of the event addressed the large-scale copyright infringement inherent in this “activism.”

This is virtually identical to CIA efforts during the Cold War when balloons were used to drop millions of leaflets, copies of books and even terrorism training manuals to populations in Soviet republics or countries with left-wing governments.

It appears that the CIA not only softly helped to make The Interview but was also involved in using it as a weapon of psychological warfare against the North Korean government. Whether this was effective is unclear due to the near-total absence of reporting from inside North Korea.

Jack’s Back, and He’s Overthrowing the Venezuelan Government

Perhaps the most astonishingly blunt PR effort on behalf of the CIA and DOD’s black operations is Amazon’s Jack Ryan, a TV reboot of the Clancy franchise. Written by a former Marine, Jack Ryan has benefited from assistance from the CIA, the DOD, and the U.S. Coast Guard, which is both an adjunct of the U.S. Navy and a component of the Department of Homeland Security.

The DOD actually rejected season one after reading scripts for the first few episodes. A document from the summer of 2017 says they were “very well-written, ‘page-turners,’ but hopeless for DOD.” It seems that the depiction of a drunken, traumatized drone pilot gambling and cavorting in Las Vegas, and U.S. soldiers paying off Yemenis for the bodies of jihadis targeted in drone strikes was a bit rich for the Pentagon’s blood.

However, the episodes ultimately aired and the finished series was deemed acceptable, and heavily promoted by the U.S. military, with hundreds of uniformed servicemen attending the premiere aboard a U.S. battleship in San Pedro, near Los Angeles, during “LA Fleet Week.”

Season two of Jack Ryan shifted focus from the Middle East and the War on Terror to Russia and Venezuela. The opening episode sees Jack go down to Venezuela in search of supposed Russian nukes that had been smuggled into the country. His convoy is ambushed in a scene that is creepily reminiscent of a scene in Clear and Present Danger (1994) which, like Jack Ryan season two, was supported by the CIA and DOD.

Jack Ryan vs. Clear and Present Danger

A comparison between these two Clancy adaptations, produced more than 20 years apart, illustrates the shift in approach within the entertainment liaison offices.

Clear and Present Danger centers around the U.S. running black operations in Colombia to try to stem the flow of drugs into the U.S.—a reversal of the Iran-Contra scandal whereby the CIA was colluding with major drug traffickers in order to raise money to support the Contras in Nicaragua.

An elite special forces squad is sent into Colombia to take on the drug cartel directly, in the form of sabotage and assassinations. Early versions of the script had the President, the National Security Adviser and senior CIA officials all conspiring to run this covert operation, but this proved problematic for the military’s PR staff.

Files on the film show that the first approach from the producer was in 1991, but a U.S. Army memo reviewing the script records a fairly critical response, saying, “My real difficulty is the way our soldiers are ‘shanghaied’ into a black—superblack operation. On a larger scale, I do not see how we can support unless DOD—with the concurrence of State, CIA, Justice and the White House—agrees to support.”

The filmmakers returned in 1993 but many of the same problems remained, with the Joint Staff objecting, “These are portrayed as unilateral U.S. actions, not coordinated with the governments of the countries in which the actions take place. Latin American countries are extremely sensitive to any violations of their sovereignty.”

If only the U.S. government were as concerned with the sovereignty of Latin American countries in real life as it is in the movies.

As a result, there were many months of negotiations with the DOD, and including representations from the CIA, White House, State Department, Justice Department, FBI and others, before support was granted.

The size of the conspiracy was reduced, to make it the result of a handful of bad actors rather than outright U.S. foreign policy. The President was removed from the conspiracy and his racist comments about South Americans were deleted. The CIA involvement in the operation was reduced to a single, rogue agent, and it is made clear that the Colombian government is aware of the covert invasion and approves.

By comparison, Jack Ryan is far more explicit. Jack and his merry band of CIA cohorts have no permission to be in the country, and set about influencing an election to try to sway it in favor of their preferred candidate, just like the real CIA has been doing in Venezuela for decades.

However, the series flipped the script for a modern audience, portraying the incumbent Venezuelan president as a right-wing dictator who is facing off against a liberal human rights activist. This inverts reality, whereby the CIA has frequently supported and even installed authoritarian dictators in Latin America, often overthrowing left-wing governments in the process.

Nonetheless, the second season of Jack Ryan openly depicts the CIA operating covertly in Venezuela to shape and influence its politics, and heroizes this as necessary for U.S. national security. Even when it means Jack and his buddies chopping off people’s fingers and keeping them in the fridge as mementos.

Remember, Jack’s a man-eating shark, but he’s our man-eating shark.

Both the CIA and the DOD were fully on board with this depiction, in sharp contrast to their approach to a very similar storyline in early scripts for Clear and Present Danger. The U.S. Navy lent the producers a warship, Black Hawk helicopters play a key role in flying Jack to the presidential palace to hunt down the dictator, and star Michael Kelly was given a tour of CIA headquarters—a benefit enjoyed in season one by John Krasinski and Wendell Pierce.

Stars of Tom Clancy’s Jack Ryan who visited Langley. [Source: ew.com]

CIA consultants worked on both seasons, with Krasinski commenting “They’re always checking in with us and we’re always checking in with them.”

Normalizing the Unthinkable

We have to conclude, therefore, that, while in the past the CIA and DOD have proven very sensitive about being depicted conducting worldwide black operations, they have shifted tack by trying to normalize these activities.

As economist and media scholar Edward Herman noted, “Doing terrible things in an organized and systematic way rests on ‘normalization.’ This is the process whereby ugly, degrading, murderous, and unspeakable acts become routine and are accepted as ‘the way things are done.’”

Had Herman ever had access to the many thousands of pages of government documents now available on their relationship with Hollywood, he would undoubtedly agree that this normalization is reaching fever pitch.

The entertainment industry is openly portraying some of the darkest actions of the CIA and DOD, from death squads to coup d’états, often with the help of those selfsame agencies.

These depictions do vary, and on occasion still go too far.

For example, the most recent Clancy-verse film Without Remorse (2021)—which portrays a Navy SEAL torturing, murdering and going completely off-book—was rejected by the DOD.

Source: imdb.com

But the CIA and DOD are increasingly coming around to the view that normalization is more effective than censorship, and that portraying black ops as either heroic, or at least a necessary evil in a complex and hostile world, is working wonders for their ability to continue carrying them out.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram, @globalresearch_crg and Twitter at @crglobalization. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Tom Secker is a British-based journalist, author, and podcaster. His specialities include the security services, Hollywood, propaganda, censorship and the history of terrorism. Tom’s writing and research has appeared in The Mirror, The Express, RT, Salon, Newsweek, The Atlantic, The Independent, Harpers, Insurge Intelligence, Shadowproof, TechDirt and elsewhere. Tom can be reached at [email protected].

Featured image: Harrison Ford as Jack Ryan flashing CIA card in Tom Clancy remake, Clear and Present Danger (1994). [Source: hollywoodreporter.com]