Between Horror and Hope. An Interview with John Pilger. His Legacy Will Live!

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

New Year Donation Drive: Global Research Is Committed to the “Unspoken Truth”

*

John Pilger has been winning awards since 1966, for his journalism and, later, his documentary film-making. Harold Pinter observed: ‘He unearths, with steely attention to facts, the filthy truth, and tells it as it is.’ The Financial Times, on the other hand, has called him ‘a master propagandist’.

Huw Spanner began corresponding with him by email on 2 November 2020.

***

Huw Spanner (HS): We’re starting this conversation on the very eve of the US presidential election. What do you think is at stake?

John Pilger (JP): Well, Donald Trump is a caricature of the American system and Joe Biden is the embodiment of the American system. Either way, we shall end up with an American President. There will be superficial changes if Trump loses, but the system will not change. The rich will continue to grow richer, and the poor poorer. The majority of people – Americans and the rest of us – will be the losers.

What is known as ‘American foreign policy’ will continue to promote violence, plunder and lawlessness across the world, ignoring sovereignty and abandoning democracy and diplomacy in a bid to restore America’s perceived dominance of 25 years ago. This ‘mission’ is bipartisan to both Republicans and Democrats, though it is based on the mostly liberal belief that ‘exceptional’ America has the divine right to do as it wishes.

The priority is to subvert China and Russia and influence or overthrow their governments. This is unlikely to succeed, but what may happen is open warfare, especially nuclear war in Asia, by mistake. Russia is almost as well defended as the Soviet Union was; and China is rapidly (and reluctantly) preparing seriously to defend itself. ‘For the first time,’ says the respected Union of Concerned Scientists in the US, ‘China is discussing putting its nuclear missiles on high alert … This would be a significant – and dangerous – change in Chinese policy.’1

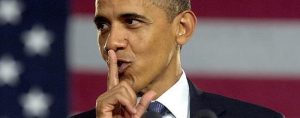

President Obama, who [in 2009] was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize, initiated an entirely unnecessary bellicose campaign against China. While declaring that he was freeing the world from the ‘tyranny’ of nuclear weapons, he secretly increased America’s production of nuclear warheads at a faster rate than any President during the first Cold War.

This is important to understand, because the so-called news these days is so integrated into Anglo-America’s rapacious planning, and the deceit that accompanies it, that most people haven’t a clue what our governments are doing. They still look favourably on Obama and regard Trump as a maniac – which he may well be, but no more maniacal than his predecessors, if their policies and actions are a measure. With Joe Biden at his side, Obama started seven wars, a presidential record.2

HS: I take your point about Obama’s record overseas, but still most people would say that he’s a decent and principled man.

JP: A form of ‘identity politics’ says he is, certainly – but apart from gestures, slogans, the fawning of the media, what evidence do you have that Obama was a decent and principled man?

HS: I was merely appealing to an intuition that, at a personal level, he would be a better next-door neighbour, say, or a better godfather to a child, than Trump would be. But let’s not argue about that!

JP: Some of the greatest scoundrels have been perfect godfathers (in more ways than one). Obama’s now infamous Tuesday ritual when he selected the names of those to be murdered by the US military’s drones3 – ‘suspected’ terrorists who often weren’t – would disqualify his description as a man of decency and principle.

People’s ‘intuition’ is important, but it so often needs knowledge and a consciousness.

HS: Do you believe that the US political system tends to promote to power people who are morally corrupt, or is it more that anyone in power, even if they were genuinely the best of people, would find themselves obliged to do wicked things?

JP: The short answer is that all power corrupts sooner or later, in varying forms and degrees, unless it is accountable.

HS: You’ve spent much of your life scrutinising the actions of people in power, in many parts of the world. Have you observed a pattern in how power corrupts? Are there particular fault lines in human nature?

JP: Suggesting that a ‘fault line in human nature’ is the cause of a failure of principle in some is an easy option. People in power are the product of systems, whose stewardship often requires the surrender of principle.

HS: Maybe we could take an egregious example. Some years ago, Desmond Tutu said of Aung San Suu Kyi: ‘She inspires me with her gentle determination. In the face of the viciousness of the military regime … she has demonstrated just how potent goodness is. Men, armed to the teeth, are running scared of her. When those men are no more than the flotsam and jetsam of history, her name will be emblazoned in letters of gold.’4

Nowadays, however, even Burma Campaign UK is condemning her for her government’s repressive actions – not least in imprisoning journalists.5 How do you make sense of her conduct in power?

JP: Desmond Tutu is a magnificent human being, and generous. He was being generous in saying that Suu Kyi’s name would be ‘emblazoned in letters of gold’. I, too, admired Suu Kyi. I interviewed her [in 1996] when she was under house arrest6 and corresponded with her after she was released. (I used to send her books, mainly fiction and poetry, which she appreciated.) I still admire the extraordinary fortitude with which she faced her incarcerators and the inspiration she gave her people then.

Where did her strength come from? She is a deeply religious person, and this may be part of the answer. She is also deeply conservative. The only clue that her book, Freedom from Fear,7 gives is that it offers no vision for political change. I once asked her what kind of Burma she wanted beyond elections – how she would protect her people against corporate exploitation and the notorieties of imposed debt and [International Monetary Fund] ‘structural adjustment’ regimes. The impression she gave was that she would not oppose them; it was a steely reply.

Some would describe this as a liberal pragmatism. Her current alliance with Burma’s generals, who were responsible not only for her own torment but for crimes against humanity, not least the persecution of the Rohingya, has ensured her a place at their table. She has refused to defend the Rohingya, a minority defamed by Burma’s extremist monks. Is she influenced by them? Or is she simply the ‘pragmatist’ who retains power by turning away from inconvenient horrors? As the latter, she would fit comfortably into the Western system of ‘democracy’.

HS: You have documented so much injustice and suffering around the world, generally among those who have the least resources. Are they inevitable ‘collateral damage’?

JP: ‘Collateral damage’ is a cynical term used by militaries (and corporations) to distance themselves from the consequences of their actions. As for it being ‘inevitable’, I don’t see what is inevitable about injustice and suffering among ‘those who have least resources’ when resources are denied them. Some 1,200 children die from malaria every day, says Unicef.8 They die in countries denied resources to which they have a right and which are their own sovereign wealth.

Unless you believe in a divinity, nothing is inevitable.

HS: Can you envisage a system of government that would not ‘require the surrender of principle’ but would genuinely allow decent people to exercise power justly and humanely? Have you seen such a system in your travels around the world?

JP: A system of government that does not require the surrender of principle is one that strives to deliver political, social and economic justice. Yes, I can envisage it – as long as I don’t have to envisage perfection. As human beings are less than perfect, their best-laid plans will be flawed. And yes, I have seen parts of systems that exercise power justly and humanely.

This power may be compromised as a reformist or revolutionary government struggles to prevent its subversion by both domestic and foreign influences. Still, principle is not necessarily surrendered, or it is preserved in a shared popular memory. Latin America offers up striking examples of this. In all societies, there is always a seed beneath the snow.

HS: That is a very hopeful image! The optimism of it puts me in mind of the slogan El pueblo unido jamás será vencido (though it strikes me that ‘never being defeated’ is not quite the same thing as being victorious).

JP: Yes, it is hopeful. Perhaps what truly distinguishes humanity from other species is not so much our brainpower as our optimism. That seems extraordinary to say at a grim time like this, but even when we fail to recognise it, optimism is our motor. It moves us on the greyest morning; it fools me into believing I can do more than my faculties allow – that I can swim up the wall of a wave before it breaks, as I did when I was 21. Audacity is always necessary: just enough to ensure we ‘go on’.

Those who struggle against the odds for principle and justice may pause and rest, but they ‘go on’. I have met so many of them, and invariably I leave their company optimistic. Ahmed Kathrada – I knew him as ‘Kathy’ – spent 18 years on Robben Island as a political prisoner with Nelson Mandela. When I returned to South Africa after my long banning, he took me to Robben Island and his cell, turning the key in what looked like a stone closet, five feet by five feet. When we entered, the two of us filled it. ‘I slept on the floor for the first 14 years,’ he said. ‘I had a raffia mat, that’s all. And the light was always on, always burning bright.’

Such sheer moral and physical courage, limitless ingenuity and what I can only describe as ‘optimism of the spirit and purpose’ kept Kathy and his comrades going. Of course they were exceptional, but there are a lot of exceptional people.

HS: Are you confident of the ultimate victory of el pueblo (as Tutu was in South Africa9), or do you foresee that the struggle will go on forever? Are world affairs essentially chaotic, or do you see prevailing winds and currents that are carrying us all inexorably in one direction? Lately, there have been dramatic twists in the story in Ecuador,10 Brazil11 and Bolivia,12 but do they fit into any coherent larger narrative?

JP: As you say, there have been ‘dramatic’ shifts in many countries lately – in 2019 Bolivia saw a coup that overthrew the reformist indigenous government of Evo Morales. And yet, within a year, the people had risen up, demanded a new election and voted by a landslide to throw out the coup plotters. The exiled Morales is now back in Bolivia. If we were served with real news, that astonishing turnaround – and its poder del pueblo,13 as they still say in Latin America – might have cheered some of us up.

Even in times as gloomy as these, the breeze can change suddenly, unexpectedly. Few predicted the restoration of democracy in Bolivia. Precious few foresaw the end of apartheid or the fall of the Berlin Wall. I didn’t; I should have been more optimistic.

HS: Your recent column titled ‘Another Hiroshima is Coming… Unless We Stop It Now’ began with the image of ‘the shadow on the steps’: the silhouette of a young woman burnt into the granite by the flash of the atom bomb in 1945. You wrote that on your visit in 1967 you ‘stared at the shadow for an hour or more.’14

I’ve read that you like to ‘mull’. Can you say what was going through your mind then?

JP: When I first saw dead young soldiers on a battlefield, their new boots upended in the stillness, I stared at them. How could this be? The Hiroshima shadow was different. The woman on the steps of the bank was not on a battlefield. There were no soldiers; she was not meant to be in immediate danger – Hiroshima was a civilian city going about its normal business. She was vaporised waiting for a high-street bank to open. (That’s why Peter Watkins’ The War Game15 is so disturbing and memorable – it shows the criminal terror of nuclear war.)

I was mesmerised by the shadow because it was evidence of something that was beyond the imagination, yet it touched almost every nerve. [The great US war correspondent] Martha Gellhorn and I talked about this, and she spoke about her similar reaction to the horror of reporting just-liberated Dachau.

‘Mulling’ – now, that is altogether different! It’s serene, relaxing, a switch-off, an escape. My mother used to say of me, ‘His head is always in the clouds.’ I think I trained it to come down to earth. A pity.

HS: An online review of your pick of other writers’ investigative journalism, Tell Me No Lies,16 observed: ‘It engenders a feeling of intense rage.’ Is anger an important ingredient in your work and the work you admire? Or should a journalist seek to be objective and dispassionate?

JP: From memory, Tell Me No Lies was generally received not as a work of ‘rage’ but as a celebration of enlightening and humane investigative journalism.

Rage or anger on their own are pointless, or worse. Much of the media directs phoney rage at its assorted targets. Of course, if you are not genuinely angered by injustice, or duplicity, on the part of power, you have allowed your humanity to be appropriated. The dispassion or objectivity you cite is often intended to disguise political bias – the BBC are especially skilled at this sleight of hand.

I recommend the quote on the jacket of Tell Me No Lies by T D Allman, one of America’s finest journalists: ‘Genuine objective journalism not only gets the facts right, it gets the meaning of events right. It is compelling not only today, but stands the test of time. It is validated not only by “reliable sources” but by the unfolding of history. It is journalism that 10, 20, 50 years after the fact still holds up a true and intelligent mirror to events.’

HS: I can see that much that passes for journalism misrepresents or misinterprets events, whether inadvertently or deliberately; but do you think one can say (as Allman would seem to imply) that events have a single ‘meaning’ and that it is possible for a good journalist to get it right?

It’s often said that journalism is ‘a first rough draft of history’, and history is often revised (or often needs to be), surely?

JP: Does anything have a single meaning? Contradictions often rule us as human beings, so why should man-made actions be different?

Journalism is a rough draft of history in very few cases: for example, William Howard Russell’s reporting from the Crimea, Wilfred Burchett’s reporting from Hiroshima, Morgan Philips Price’s reporting from 1917 Russia. As journalists, they got the historical meaning of momentous events right at the time – but that’s rare!

HS: You often quote the maxim ‘Never believe anything until it has been officially denied.’ In recent years, there has been a huge loss of trust in ‘the government line’,17 but in many cases it would seem that what has replaced that trust is not a healthy, informed scepticism but a willingness to believe everything under the sun.18 Does this make the task of the investigative journalist harder in some ways, or merely different?

JP: My sense is that the trust in government and parliamentary politics began to die with Harold Wilson’s Labour government [in 1964–70]. Perhaps it recovered briefly in 2017 when Jeremy Corbyn19 – or the movement outside his party that he represented – seemed to promise so much.

I would say it’s now rock-bottom. There are spivs in power and the corruption that produced them runs through the sinews of the civil service they have politicised. Revolving doors now spin between government, the Civil Service and the casino world of voracious corporatism. Imagine a few years ago a company as rotten as Serco given tens of millions of pounds to turn back an epidemic,20 or a ‘venture capitalist’ (married to a Tory minister) running the nation’s vaccination programme!21

Read The Plot against the NHS by Colin Leys and Stewart Player,22 who document how the Department of Health was Americanised and subverted by management consultants and assorted parasitic enemies of public health. The way this British government has handled the pandemic is scandalous. There will surely be a reckoning – but in what form?

I don’t agree that people now ‘believe everything under the sun’. A great many of us are disorientated politically because we are unrepresented in a system devoted to inequity and insecurity. There is no real political opposition in Parliament to the extremism of those in charge. It is as if power speaks with a united, almost evangelical voice. Brexit was for a great many Britons a protest vote, a cry of resistance.

HS: That takes us back to the ‘meaning’ of events. Two days after the 2016 referendum, you published a column titled ‘Why the British Said No to Europe’,23 in which you said that ‘millions of ordinary people refused to be bullied, intimidated and dismissed with open contempt by their presumed betters in the major parties, the leaders of the business and banking oligarchy and the media.’

That seems simplistic to me. I wonder what you would say about the (marginally fewer) people who voted to stay in the EU: that they were happy to be ‘bullied, intimidated and dismissed with open contempt’? Or that they refused to be led by the nose by Johnson,24 Farage25 et al?

JP: I am sorry if you regard my view as simplistic. The propaganda that so many ordinary Britons were racists or stupid was very much a liberal, metropolitan view. The group of far-right extremists who appropriated the Brexit cause – the cynical Johnson and the small cabal of nationalists – did not represent the majority but provided juicy media fodder.

HS: Last August, a French journalist26 commented that if Johnson was running France, there would be daily demonstrations and a general strike. Do you think that generally the British are more docile, or compliant, politically than other nations?

JP: The Chartists, the great Liverpool resistance during the General Strike, the RAF mutineers, the miners, the dockers, the Greenham Common women’s movement, the Poll Tax movement, the anti-Iraq invasion movement, Extinction Rebellion and so on and on… docile? I don’t think so.

In their own way, the British are far more rebellious, and politically and culturally adventurous, than many nations – certainly more so than my own compatriots. That’s why the arts and comedy, and science and sheer enlightened invention, have flourished.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Notes

[1] ucsusa.org/…/China-Hair-Trigger-full-report.pdf

[2] See independent.co.uk/news.

[3] See nytimes.com.

[4] See burmacampaign.org.uk/the-lady-of-burma.

[5] burmacampaign.org.uk/new-campaign

[6] johnpilger.com/…/portrait-of-courage

[7] Freedom from Fear: And other writings (Viking, 1991)

[8] unicef.org/media

[9] See eg goodreads.com/quotes.

[10] jacobinmag.com/2019

[11] blogs.lse.ac.uk/latamcaribbean

[13] ‘People power’

[15] See bbc.co.uk/programmes. The drama-documentary was commissioned by the BBC in 1965 but has been televised only once, in 1985 (despite winning the 1967 Oscar for best documentary feature).

[16] Tell Me No Lies: Investigative journalism and its triumphs (Jonathan Cape, 2004)

[17] See eg politico.eu/article.

[18] See eg theguardian.com/us-news and newstatesman.com.

[19] Interviewed for High Profile in June 2015

[20] See opendemocracy.net.

[21] Kate Bingham, who is married to the Treasury minister Jesse Norman and is a managing partner in SV Health Investors

[22] Published by the Merlin Press in 2011

[24] Boris Johnson, interviewed for High Profile in August 2004

[25] Nigel Farage, interviewed for High Profile in December 2011

[26] Marion Van Renterghem, quoted in thearticle.com

Featured image is from High Profiles