Behind the Saudi-led Blockade of Qatar

A blockade imposed on Qatar by Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Bahrain and Egypt entered its third month in August as negotiations to end it remained deadlocked. The comprehensive blockade cuts diplomatic relations between the countries, closes borders and land, air and sea routes, and even prohibits citizens of the boycotting nations from working in Qatar. Iran has rushed to Qatar’s aid and is flying large food shipments into the country.

The main reasons given for the blockade by Saudi Arabia and the other three countries are Qatar’s alleged support for terrorism (especially its close links to the Muslim Brotherhood party in Egypt), its interference in their internal affairs, the news channel Al Jazeera and Qatar’s good relations with Iran. The four blockading countries have issued thirteen demands to Qatar that include closing Al Jazeera, downgrading trade relations with Iran, expelling the “terrorists” it is harbouring, ceasing other support for terrorism, closing a Turkish military base and bringing its foreign policy in line with that of the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC), a regional political organization to which Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, the UAE, Oman, Kuwait and Qatar all belong.

Qatar has rejected these demands as an attack on its sovereignty. All the countries in the dispute are U.S. client states, competing for Washington’s approval, but the White House itself is divided on the issue, with U.S. diplomacy now hobbled by a contradictory foreign policy. The blockade is opposed by Rex Tillerson, the U.S. secretary of state, but was encouraged by President Donald Trump during his visit in May to Saudi Arabia. Tillerson’s shuttle diplomacy amongst the conflicted countries in July failed to break the deadlock. Qatar hosts the biggest U.S. military base in the Middle East, which houses an estimated 10,000 troops.

Conn Hallinan, an analyst with Foreign Policy in Focus, a project of the Washington, D.C.–based Institute for Policy Studies, explains that Trump’s trip to Saudi Arabia was a major reason for his supporting the Qatar blockade.

“Trump is deeply ignorant on foreign policy and particularly so in the Middle East,” he says. “The Saudis threw him a dog and pony show and he took the bait.

“Trump has since backed away — a little — from his blanket support for the blockade. A major reason is that Qatar is strategically important for the U.S.”

Hallinan cautions that Tillerson “may not support the blockade against Qatar but he still holds to the 1979 Carter Doctrine that gives the U.S. the unilateral right to intervene in the Middle East to preserve the control of energy resources for Washington and its allies.”

Sabah Al-Mukhtar, president of the Arab Lawyers Association based in London, U.K., tells me the dispute

“has nothing to do with terrorism, which is supported by Saudi Arabia and the UAE as well.” These countries, as well as Qatar, “were ordered by the United States to support the uprising against President Assad in Syria and the use of force to overthrow him, and all three countries have been financing terrorist groups in Syria to accomplish this. So, Saudi Arabia accusing Qatar of supporting terrorism is laughable.”

Al-Mukhtar adds that the UAE’s trade relations with Iran are more extensive than those of Qatar, and that the funding and promotion of Al Jazeera, a television news channel that broadcasts in Arabic across the Middle East, is the most important factor in the blockade, since the channel’s news programs regularly feature Arab commentators who talk about human rights and how governments should answer to the people.

“This is anathema to the four blockading regimes who think the channel is undermining them and provoking unrest in their populations,” he says.

A second major reason for the blockade is the shared Saudi and U.S. fear of Iran’s growing power. They want to isolate Iran, a majority Shia Muslim country, in part by pitting it against a united Sunni (the majority sect of Islam) front of countries. The Obama administration had opted for diplomacy, signing a nuclear pact with Tehran as part of efforts to normalize relations, but Trump is far more hostile to the country, which suits the Saudi Arabian monarchy much better.

“The Saudis fear that Iran’s nuclear pact with the U.S., the EU and the UN is allowing Tehran to break out of its economic isolation and turn itself into a rival power centre in the Middle East,” explains Hallinan. “They also fear that anything but a united front by the GCC — led by Riyadh — will en -courage the House of Saud’s internal and external critics. Such fears have driven the Saudis to make what I think is a major strategic error. The blockade is not working.”

Instead of separating Qatar from Iran, the blockade has driven the two countries closer together. Even within the GCC, the blockade is not unanimously accepted, with Oman and Kuwait refusing to boycott Qatar. Hallinan adds that Egypt, which supports the blockade, will not break relations with Iran. Other Muslim countries such as Pakistan and Indonesia reject both the blockade and chilling relations with Iran, while Morocco and Turkey are sending Qatar supplies.

“The new Saudi regime has made one mistake after another,” says Hallinan. “It invaded Yemen, thinking it would be a short war, despite being told that the only place you want to invade less than Afghanistan is Yemen. They pushed down the price of oil, thinking it would drive marginal competition out of business and somehow missed the analysis that the Chinese economy is slowing down, so they are stuck with low oil prices draining their income. The combination of incompetence and arrogance is just breathtaking.”

Hallinan says this record of failure is matched by that of the U.S. It started with George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq, followed by Obama’s overthrow of the Libyan government and his administration’s support for the overthrow of Assad in Syria. “One can add U.S. support for the Saudis in Yemen. All these actions have increased Iranian influence, and Russian as well, in the Middle East,” he argues. The Iraq war removed Iran’s biggest rival in the region and established a Shia government in Baghdad. Trump’s encouragement of the Qatar blockade is just the latest U.S. gift to Iran.

Qatar is the world’s third largest producer of natural gas (after Iran and Russia) and shares ownership with Iran of the North Dome/South Pars maritime gas reserves, which make up 14% of world gas deposits. This has made Qatar, with a population of two million, the richest country per capita in the world. It also makes Qatar economically very strategic.

“The blockade of Qatar has been carried out by Saudi Arabia in consultation with Washington and I suspect that its main motive is to break this sharing arrangement for natural gas between Qatar and Iran,” says Michel Chossudovsky, an emeritus professor of economics at the University of Ottawa who visited Qatar in July.

The U.S. objective is, he claims, to secure geopolitical control over Qatar’s gas reserves — a familiar motive lurking behind many other cases of U.S. intervention globally.

Chossudovsky points out that Qatar’s maritime gas fields are entirely owned by the state; private corporations, including ExxonMobil and several other compa -nies from Russia, China and Malaysia operate under contracts. In December, Qatar’s close relations with Russia bore fruit when the state-owned Qatar Investment Authority bought (with Swiss commodities trader Glencore) 19% of Rosneft, a Russian oil corporation also invested in Qatar’s gas sector.

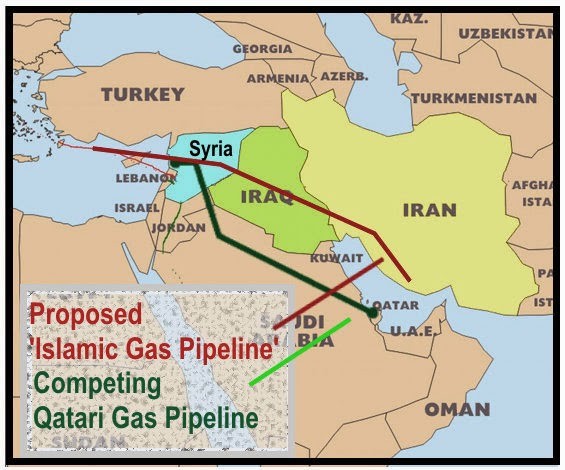

For years, the U.S. has been unsuccessfully attempting to find an alternative to Russian gas supplies for Europe by running a pipeline from the Middle East or Central Asia to the continent, as I wrote about in the Monitor in May 2010. Russia is the biggest supplier of both oil and gas to Europe. But according to Chossudovsky, a major effect of the blockade will be to change planned pipeline routes for Qatar’s gas from travelling through Saudi Arabia to Europe to going through Iran (via Iraq and Syria). This is the route backed by Russia.

“Russia’s geopolitical control over gas pipelines going to Europe has been reinforced as a result of the blockade,” he says.

It’s too early to say the U.S. has been beaten at its own game. Washington still has substantial influence over Qatar due to its military base there, and the blockade has made Qatar more anxious than ever to gain U.S. favour, according to Al-Mukhtar. In July, Tillerson announced the U.S. and Qatar had signed a memorandum of understanding on fighting terrorism that includes substantial financial information sharing.

“Together, the U.S. and Qatar will do more to track down funding sources, collaborate and share information and do more to keep the region and our homeland safe,” said the secretary of state, adding the deal had been two years in the making.

At the same time, as Al-Mukhtar emphasizes, Iran is also established as a major power in the Middle East, a development the U.S. was unable to prevent. Qatar’s close alignment with both countries — the U.S. and Iran — reflects this complex new reality in the Middle East.

Asad Ismi is the CCPA Monitor’s international affair’s correspondent. He has written extensively on the Middle East and U.S. imperialism. For his publications visit www.asadismi.info.

This article was originally published in the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Monitor, September-October 2017 (p. 54)