Battle for Mosul, Defeat of the ISIS Caliphate, A Year of Brutal War, Crimes against Humanity

Iraq's fight to liberate Mosul from IS was one of the biggest stories of 2017. Here is the best reporting on the conflict from Middle East Eye

The Islamic State (IS) group shocked the world when, in 2014, it walked a few hundred men into Iraq’s second city and took it from 30,000 fleeing Iraqi troops. Days later, IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi declared a caliphate from the city’s historic Nouri mosque.

Almost three years on, in October 2016, the Iraqi government launched operations to retake the city. What followed was one of the most intense and brutal urban conflicts for generations.

Middle East Eye special correspondents witnessed events unfold, and documented the violence, exhaustion, hardship, fear and celebration as the city was slowly liberated during 2017. Here is the pick of their reports on one of the biggest stories of the year. Click on the pictures below to read the articles in full.

By January of 2017 Iraqi forces had stuck several blows against Islamic State. Eastern outlying villages had been cleared of militants, and many of the urban areas east of the Tigris river were under tentative Iraqi control. By mid-January commanders were declaring the full liberation of the east of the city.

But the hardest fighting was yet to come, and Islamic State was not finished in the east.

As Tom Westcott reported on 29 January, the Jungle, the sprawling leafy eastern banks of the Tigris river, where roads ran alongside deserted fairgrounds and hotels – perfect for ambushes – became the last eastern strongpoint for IS and final advances made under constant risk of sniper fire, was the only option for Iraqi troops from the elite Golden Division. Click on the pictures to read in full.

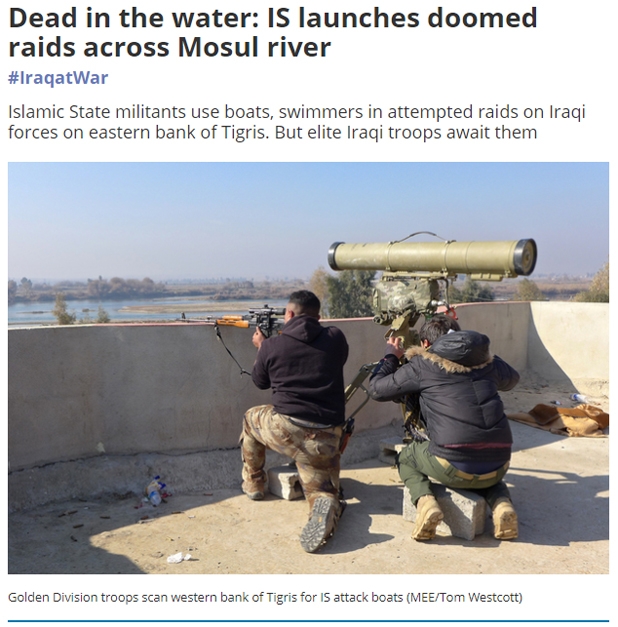

By February, Iraqi forces had pushed Islamic State back to the western bank of the Tigris. But the group refused to concede the ground, sending frogmen across the river to harass and disrupt troops stationed along the banks.

Westcott, reporting from an Iraqi forward position along the river, told on 1 February how the Iraqi forces stopped their enemies dead in the water.

By the end of the month, Iraqi forces had consolidated their hold on eastern Mosul – but it was far from safe. Westcott, this time reporting from behind the front lines in liberated areas, detailed on 22 February how IS was using small drones to drop bombs on anything that moved.

The drones were used without warning and often with deadly precision. “You can’t leave the house without checking the sky every single second and, even if you hear one of the drones, you don’t have time to run because they are so fast,” said one civilian, who recounted how his neighbour had been seriously injured by a grenade dropped from the sky.

Hospitals said they were treating up to 10 people a day for injuries suffered in the drone attacks.

Iraqi advances into the city would not have been so decisive had it not been for the air power of the US-led coalition. But that trump card came with a heavy price, especially as fighting reached a crescendo as forces moved into western Mosul.

Airwars, a monitoring group, analysed the civilian cost of fighting in urban areas – something the US coalition itself was unable to do in as much detail.

On 8 March, Alessandro Accorsi reported US coalition bombs may have already killed hundreds of Mosul civilians, including up to 130 in a single assault on the district of Dawassa only days before.

A US military spokesman told Middle East Eye the coalition would “fully assess this allegation to assess its validity”. In October, the US military stated the Airwars report “contains insufficient information of the time, location and details to assess its credibility”.

By mid-March, as Iraqi forces pushed into the west of the city, the true scale of destruction by Islamic State became apparent.

The ancient history of Mosul had been desecrated by IS militants, who viewed many non-Islamic artefacts and architecture as forbidden.

Their answer was to smash it to pieces – and Mosul’s once-proud museum lay in ruins on its liberation. Tom Westcott reported from the remains of the museum on 14 March.

In one interview in the remains of a block of homes hit by air strikes Abu Ahmed, a civilian, recounted the overwhelming use of force: “This block was hit by 14 air strikes targeting two Daesh fighters. Now we have nothing left.”

Another civilian confirmed the tactic: “The aircraft see one Daesh guy on the roof and drop a bomb. In the basement below, a family of 10 are sheltering and they get killed too.”

With the battle moving in Iraq’s favour, reports began to turn to the increasingly desperate tactics employed by Islamic State. Their use of children – so-called “young lions of the caliphate” – as frontline soldiers was in full swing.

Francesca Manocchi, on 25 March, reported how IS over three years had snatched children from their families, trained them to kill, and turned them loose on their home city.

The report began with the harrowing account of one Iraqi soldier, Hasan, who faced a horrific life-or-death choice: kill, or be killed, by a 10-year-old suicide bomber.

Increasing numbers of IS militants began to melt into the civilian population as more territory was lost to Iraqi forces. For the army, the answer was to round up all men of fighting age and “process” them at temporary sites dotted around the city.

But the task was huge, laborious, fraught with danger, and exacted a terrible toll on many innocents caught in the system. Tom Westcott, reporting on 27 March from Akrab, recounted how the Iraqi army rooted out suspects from the masses of tired, scared and hungry men.

As yet another man, who had handed himself in as an Islamic State emir, disappeared for interrogation, an Iraqi soldier offered a chillingly frank confession as to his fate:

The fate of captured IS fighters was not always the same. Just behind the front lines in western Mosul, with suicide bombs exploding and the rattle of gunfire all around, one group of volunteer medics from the US sheltered in a makeshift hospital and did their best to treat anyone who came through their doors.

Jannie Schipper, on 13 April, reported how not everyone in the emergency room agreed with the policy.

“He is 100 percent IS,” a translator claimed, as an 18-year-old was dragged in with terrible injuries. “He killed many people himself. He had already been judged and condemned to death.”

The medics continued their work.

Despite the ongoing destruction and death, resolute Mosul residents began picking up the pieces of their pre-Islamic State lives.

An 18 April report by Sam Kimball showed how the Shabak minority returned to what was left in their homes to begin again.

In May, Quentin Muller reported how music, banned by Islamic State, once again filled the streets of the city, while Laurene Daycard met a Mosul woman who had run an “illegal” beauty salon during IS occupation, paying militants off before her husband was finally arrested and beaten.

She was now free to run her business and customers were slowly starting to return. “But they are still afraid that IS may come back. I am still afraid,” she said.

By July, the fighting had all but ended, but not without terrible losses in the Iraqi army and further destruction of the city.

The Nouri mosque, the 800-year-old monument where IS leader Baghdadi had declared his so-called caliphate, lay in ruins, destroyed by retreating IS as a last insult to the city and Iraq.

As the historic Old City was bombarded with air strikes, the civilian population of western Mosul either cowered in their basements or had fled for refugee camps outside the city.

Rumours had surfaced of blanket shoot-to-kill tactics of Iraqi soldiers exhausted by months of street-to-street fighting and still facing fanatical suicide attackers, and allegations of cruelty to civilians from both sides.

After the Old City was declared liberated, a special MEE correspondent gained access to what was left. On 26 July their report laid bare in terrible detail a graveyard of human remains, filth and rubble where exhausted soldiers relayed stories of the last unforgiving days of fighting, as bulldozers made short work of covering over what many have described as war crimes.

The Iraqi prime minister, Haider al-Abadi, promised to investigate the reports. The results of that investigation are pending.

By August, two weeks after the horror of the Old City was laid bare, Mosul was still picking through the rubble for those who had not survived.

Tom Westcott gained access to the aftermath, and followed a family to their crumpled former home as they looked for the remains of their relatives. “My whole family was here when the air strikes hit and only five of us got out alive,” Omar Zwar, 25, told Middle East Eye. “It killed eight of my family. Most of them were under the rubble, and I tried to cover the other bodies as best as I could with stones before we fled.”

In other areas of west Mosul, spared the carnage of Islamic State’s last stand, life began to normalise. In one district, a young local entrepreneur saw his opportunity to bring back all that had been banned by the group – playing cards, dominoes, mobile phone accessories. But the shopkeeper had one stand-out line for sale: shisha pipes and tobacco.

For Mosulis who had endured three years of occupation and months of bitter fighting, once-forbidden pleasures gave some comfort.

Westcott met 16-year-old Abdel Halek in his tiny shop in al-Jadida.

With fighting ended and Iraqi soldiers mopping up IS resistance elsewhere, the focus fell once again in October on the actions of coalition aircraft in the battle for Mosul.

An analysis of Britain’s role in the campaign against Islamic State by Jamie Merrill discovered the RAF had dropped 3,400 bombs on targets in Syria and Iraq, the vast majority falling around Mosul.

Civilians were being ruthlessly exploited by IS, which had moved them into conflict zones, used them as human shields, and prevented escape.

The British government maintained that there was “no evidence” their bombs had killed a single civilian.

As the dust settled on Mosul, one man above all was lauded as its saviour – Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi.

Abadi had been sworn in only weeks after IS had taken the city, to wide expectation of failure. He now stands as the strong leader Iraqis needed, defeating not only IS but also an attempted breakaway by the leaders of Iraqi Kurdistan in September.

But, as Suadad al-Sahly reported in November, the recapture of Mosul was only one problem solved, and Iraq faces many more in the coming years.