The Battle for Chile

It all started with a minor misdemeanour by school students who collectively refused to pay fares on the Santiago metro in rejection of a price hike (to 830 pesos: US$1.17). This was part of a brutal austerity package, decreed by Chile’s President, Sebastián Piñera on 6th October 2019.

***

On October 18-19, 78 metro stations, some banks, 16 buses and a few public buildings were set on fire by mysterious hooded men who were able to operate with impunity. On October 19, Eric Campos, President of the Metro Workers’ Union, declared,

“strange that the Police who were supposed to have been guarding the stations, were not there when they were set on fire.”1

On Oct 18, Piñera declared a state of emergency (not used since 1987 under Pinochet), which included a curfew and, in typical neoliberal fashion, brutal police repression. He deployed the army against the civilian population. Next day Piñera promised to freeze the metro price hike hoping, unsuccessfully, to defuse the protests. Demonstrations kept growing, so on October 20 he expanded the state of emergency to most of the country. He said his government was “at war against a powerful and implacable enemy.” Repression intensified massively, with many killed by both police and the military. This infuriated Chileans thus making the demonstrations stronger, larger, more militant and spreading the length of the country.

No matter how brutal the repression, defying state of emergency and curfew, they continued to demonstrate in ever-larger numbers and involving growing sections of the middle class. Actors, pop artists, celebrities, and football players joined.

Mainstream journalists spread fake news, broadcast lies, attributing all violence and the crisis to vandalism, delinquency and ‘external forces.’ They became the target of hostility from protestors. Grotesquely, Luis Almagro, Secretary General of the Organization of American States, issued a statement blaming Venezuela and Cuba for the events in Chile.2

Soldiers and police officers perpetrated gross violations of human rights, including shooting demonstrators at point blank, beating them to death, firing live ammunition, and torturing, denigrating, degrading, beating and raping women and detainees. There are thousands of videos filmed by bystanders, protestors, and the victims themselves of these atrocities (videos show, for example, police officers stacking a patrol car’s boot with plasma TV sets; another shows soldiers throwing the body of a dead detainee from a moving police van, and threatening neighbours not to look).3 Chileans were not intimidated and continued to stage demonstrations defying the curfew, the military, the police, and the government.

On October 23, a thoroughly deflated Piñera, went publicly to apologise for “not having understood” that millions of Chileans were complaining about the unacceptable levels of social and economic inequality. He announced the suspension of the austerity package and the implementation of some palliatives.

This ‘Chilean model’ involves some impressive macroeconomic figures such as a GDP per capita of around US$19,000 and a reduction of poverty from 38,6% in 1990 to about 8% in 2019. However, this rather than being an “oasis” is in fact, a mirage.

Most Chileans have very low pensions; in 2013, 1,031,025 pensioners got an average pension of 183.213 pesos (87% of the minimum wage). Women pensioners are paid even less. Meanwhile, pension companies continue to extract contributions monthly from about 10 million workers.

Inequality in Chile is gross: the richest fifth of households receive 71% of GDP, whilst four fifths receive the remaining 29%.4 Half of salary earners in Chile take home 350.000 pesos monthly (US$481), with 74.3% earning less that 500.000 pesos (US$688).5

Health is privatized through a health insurance system with highly restrictive policies that benefit powerful companies. In 2018, through price hikes the key six companies made as much profit in one quarter as they did in the whole of 2017.

The public system of health serves 80% of the population, but is ramshackle, deficient, short of resources, and has extremely long waiting lists for operations and/or specialised treatment. Three national chains of pharmacies control 92% of the sales6, charge prices arbitrarily and, illegally collude to fix prices to the detriment of consumers, patients and the poor.

The transport system is one of the most expensive in Latin America, is inefficient and unable to resolve the transport needs of Santiago (city of six million); it generates annual deficits for being linked to a private bus service that gets most of the proceedings. Water, gas, electricity, and telephone have been privatised leading to constant and arbitrary price increases.

There is a recent gratuity for university education for about 60% of the population, but the system remains elitist. Working class kids go to poor schools, get poor-quality education, and are unlikely to be equipped to get into higher education. Thus, there is little social mobility leading most people to end up in the 80% that earn less than 500.000 pesos.

People find a way out by getting into debt, irresponsibly and widely available at exorbitant interest rates. Supermarkets and retail chains issue credit cards for purchases in their stores. Thus in 2019, 55% of household national debt is from consumption (21% from mortgages).7

Chileans have also seen how easy is for the rich to evade taxes; have witnessed major corruption scandals among politicians (mainly, but not exclusively from the right), but also the massive embezzlements in the Army and Police Force, with generals pocketing millions of public money.

No wonder Chileans were on the move. On October 23 Chile’s trade unions declared a general strike, and on Friday 25, people staged the largest demonstration in Chile’s history with 1.2 million in Santiago plus huge rallies in cities throughout the country. They demanded Piñera resign.

On Saturday 26 October Piñera announced he had asked for the resignation of all his ministers pointing out that a new cabinet (and government) was being formed, promising to lift the state of emergency. The defeat of his austerity package was complete and the question is how will the change of the neoliberal model be carried out. The mass movement has no apparent leadership, and it has no tangible political vehicle to articulate its demands. Even more interesting, Allende’s generation, their children, and their grandchildren marched and resisted together.

Allende’s image became common in thousands of the mobilizations, and the people adopted Victor Jara’s beautiful song “The right to live in peace” that he composed back in 1971 in homage to Ho Chi Minh and the people of Vietnam, as their hymn. Allende’s dream is very alive and the masses have not forgotten the moral debt Chile’s Pinochetista Right owes society for the coup in 1973, the assassination of their president and, the 17 years of atrocities under their dictatorship.

They will not forget the atrocities committed in October 2019 either, and Piñera is likely to face a constitutional accusation over them. The latest toll is 25 dead; 41 gravely wounded by firearms, 23 people gravely wounded by having been run over by police or army vehicles; 62 with severe eye trauma; more than 1700 injured; and 5845 arrested.

Chileans came onto the streets to bring the oppressive, abusive and exploitative neoliberal model to an end, but it is not yet clear what they will replace it with. A reasonable proposal involves a Constituent Assembly to replace Pinochet’s constitution, nationalization of all utilities and natural resources, punishment for corruption, respect for the ancestral land of the Mapuche, and decent health, education and pensions.

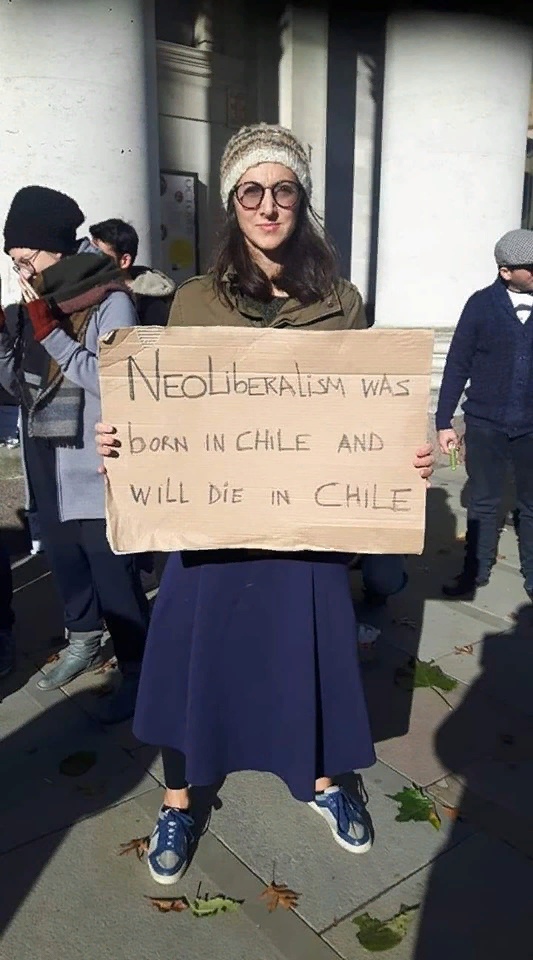

One of the biggest effects has been the well-deserved demystification their mobilisation brought on Chile’s “neoliberal miracle”. The dent they have inflicted on the already diminished prestige of neoliberalism (especially after Macri’s Argentine catastrophe and Moreno’s defeat in Ecuador) is irreparable. The New Battle for Chile will be tough and difficult, but their victory will help us the world over. All our solidarity with the struggle against neoliberalism of the Chilean people!

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

This article was originally published on Public Reading Rooms.

Dr Francisco Dominguez is a senior lecturer at Middlesex University, where he is Head of the Research Group on Latin America, and secretary of the Venezuela Solidarity Campaign. Dominguez came to Britain in 1979 as a Chilean political refuge. Ever since he has been active on Latin American issues, about which he has written and published extensively.

Notes

1 https://www.soychile.cl/Santiago/Sociedad/2019/10/19/620920/Sindicato-del-Metro-Es-extrano-que-Carabineros-haya-estado-en-las-estaciones-y-cuando-las-queman-no-esten.aspx(visited 27 October 2019).

2 Voice of America, 25 October 2019 (https://www.voanoticias.com/a/luisalmagro-oea-venezuela-cuba-latinoamerica/5140013.html – visited 27 October 2019).

3 El Comercio, Peru, 24 October 2019 (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IzLLl0247ZA – visited 27 October 2019).

4 F.Martínez & F.Uribe, Distribución de la Riqueza No Previsional de los Hogares Chilenos, Banco Central de Chile, 2017, p. 8.

5 G.Durán & M.Kremerman, Los bajos salaries en Chile, Fundación Sol, Ideas para el Buen Vivir, No14, April 2019, p. 3.

6 J.A. Chillet, “Collusive Price Leadership in Retail Pharmacies in Chile”, Semantics Scholar, 2018, p.6 (https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/f536/e84f29a75f0cd4afb219ca830be20d4b556d.pdf – visited 27 October 2019).

7 Thomas Croqueville, Indebtedness in Chile, Chile Today, 7 August 2019 (https://chiletoday.cl/site/indebtedness-in-chile-its-all-about-switching-the-bicycle/ – visited 27 October 2019).

All images in this article are from PRR