Ban Ki-moon: Requiem for a UN ‘Yes Man’

After ten years of almost total obedience to Washington, Ban Ki-moon stepped down Sunday as United Nations Secretary-General, leaving behind a sorry legacy that has undermined the U.N.’s legitimacy, which rests on its real and perceived neutrality in overseeing world affairs.

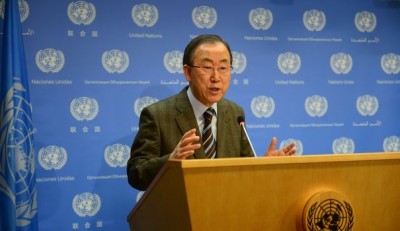

Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon delivers remarks during the special Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) segment. Sept. 20, 2016 (UN Photo)

The U.N.’s second secretary-general Dag Hammarskjold defined the job’s role as a diplomat who has the ability and courage to navigate a course independent of the major powers and in defense of the world’s population.

“The right of the Secretariat to full independence, as laid down in the Charter, is an inalienable right,” Hammarskjold said shortly after his election in 1953. The U.N.’s purpose, he said, was not to submit to the major powers but to seek “solutions which approach the common interest.”

Despite his elite background, his defense of the “common interest” distinguished Hammarskjold and alarmed many of the world’s elites who wanted a more pliable secretary-general who would reliably take their side, especially in management of the Third World. After only one year in office, he condemned the U.S.-led coup in Guatemala that overthrew a democratically elected president. No secretary-general since has publicly criticized a CIA covert operation.

Hammarskjold’s championing of the common interest of Africans and other colonized people put him at odds with the white rulers of apartheid South Africa as well as colonial Britain and the United States.

“The discretion and impartiality required of the Secretary-General may not degenerate into a policy of expedience,” Hammarskjold responded.

When he also angered the Soviet Union, which demanded his resignation, he responded: “It is very easy to resign. It is not so easy to stay on. It is very easy to bow to the wishes of a Big Power. It is another matter to resist.”

By navigating an independent course amid the major powers, Hammarskjold set the standard for the job of secretary-general – and, as I reported in 2014, it may have led to his death in a mysterious plane crash on Sept. 18, 1961, during a conflict over mineral-rich Congo.

Bending to Power

No other Secretary-General has come close to Hammarskjold’s independence or his inventiveness in creative peacekeeping and personal mediation. The few others who tried to follow in his footsteps also found their U.N. careers cut short. For instance, Boutros Boutros-Ghali’s insubordination to Washington in defending developing countries in the face of America’s post-Cold War, unilateralist expansion into spaces vacated by the Soviet Union cost him a second term. He had the temerity to tell Madeleine Albright, then the U.S. ambassador to the U.N., that Washington was his “problem.”

“Coming from a developing country,” Boutros-Ghali wrote in his memoir, “I was trained extensively in international law and diplomacy and mistakenly assumed that the great powers, especially the United States, also trained their representatives in diplomacy and accepted the value of it. But the Roman Empire had no need of diplomacy. Neither does the United States.”

Others learned their lesson. Boutros-Ghali’s successor, Kofi Annan, the only sub-Saharan secretary-general, was a major proponent of U.S. initiatives, including the controversial “responsibility to protect” doctrine of military intervention (as applied in Kosovo) and a U.N. partnership with private corporations, the so-called Global Compact, ultimately giving U.N. cover for neoliberal and multi-national misdeeds.

Though a darling of Washington, Annan got himself into hot water when he admitted to an insistent BBC interviewer that the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq was “illegal.” The Bush administration made the remainder of his second term miserable and tried to pin the Oil-for-Food scandal on him, though it was a program run by the Security Council.

By contrast, Ban, a South Korean, was seen by the Americans as their man from the start. We “got exactly what we asked for,” an administrator and not an activist, said John Bolton, America’s irascible U.N. ambassador when Ban was elected in 2005. The U.N. charter doesn’t call the secretary-general “president of the world” or “chief poet and visionary,” Bolton said sarcastically in an interview with me and a colleague for The Wall Street Journal.

Ban said his “biggest blunder” until then had been in 2001 when, as South Korea’s chairman of its nuclear test-ban treaty organization, he wrote a letter in favor of the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty just a few months after George W. Bush pulled the U.S. out of the treaty. South Korean President Kim Dae-jung issued a public apology and fired Ban for his impertinence. It was the act of a vassal state and marked Ban’s evolution into a servile diplomat.

State Department Advisers

Once Ban was installed at the U.N. in 2007, he broke with tradition by naming Americans — two former State Department diplomats — to be his chief political officers during his ten-year tenure. They brought with them a State Department perspective to the most politically influential job in the organization.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu pressed his case for the military offensive against Gaza in a meeting with UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon in 2014. (Israeli government photo)

Ban carefully toed the U.S. line in his public pronouncements. Though he privately fumed over the Saudi military bombardment in Yemen and Riyadh’s haughty dealings with the U.N., he dared not blame America’s ally.

Likewise, on occasions when Ban sharply criticized Israel for its bombardment of U.N. schools in Gaza, killing scores of innocent people, he spoke only after the State Department had made the same criticism, almost word for word.

When the whistleblower Edward Snowden revealed U.S. mass surveillance of people all over the world, Ban condemned Snowden rather than defend the common interest of the world’s population to be protected from the U.S. intelligence community’s pervasive violations of their privacy.

Regarding the geo-strategic battle of our times — America’s unilateral push for global hegemony versus an emerging multi-polar world, led by Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa — the U.N. as the world’s premier multilateral organization would have seemed like a natural ally of the BRICS, which held its first formal summit in 2006 just months before Ban took office. But Ban backed the U.S. in every geo-strategic question against Russia and China during his time in office.

On Syria, Ukraine and the South China Sea, Ban parroted Washington’s rhetoric and made no effort to mediate the disputes. He never condemned the U.S.-backed coup in Kiev or Washington’s support for violent extremists in Syria, which Russia has confronted. He called for regime change in Damascus (after Obama did.)

Regarding sensitive concerns about Western interference in Africa, Ban failed to distinguish himself on a single African issue, merely endorsing whatever the U.S., Britain and France were up to on the continent. Ban was a prominent champion in the struggle to combat climate change, but it was a position fully endorsed by the Obama administration.

The new secretary-general, Antonio Guterres of Portugal, is inheriting crises that bedeviled Ban. Guterres, a former Portuguese prime minister and head of the U.N.’s refugee agency, whom I interviewed a couple of years ago for an hour without any handlers present, is smart, realistic and outspoken in favor of multilateralism. It won’t be long before it’s known if he will cross swords with the Trump administration, in the tradition of Hammarskjold, or go the way of Ban and let Washington always get its way.

Joe Lauria is a veteran foreign-affairs journalist based at the U.N. since 1990. He has written for the Boston Globe, the London Daily Telegraph, the Johannesburg Star, the Montreal Gazette, the Wall Street Journal and other newspapers. He can be reached at [email protected] and followed on Twitter at @unjoe.