Avoiding Conflict In Asia Pacific’s Waters

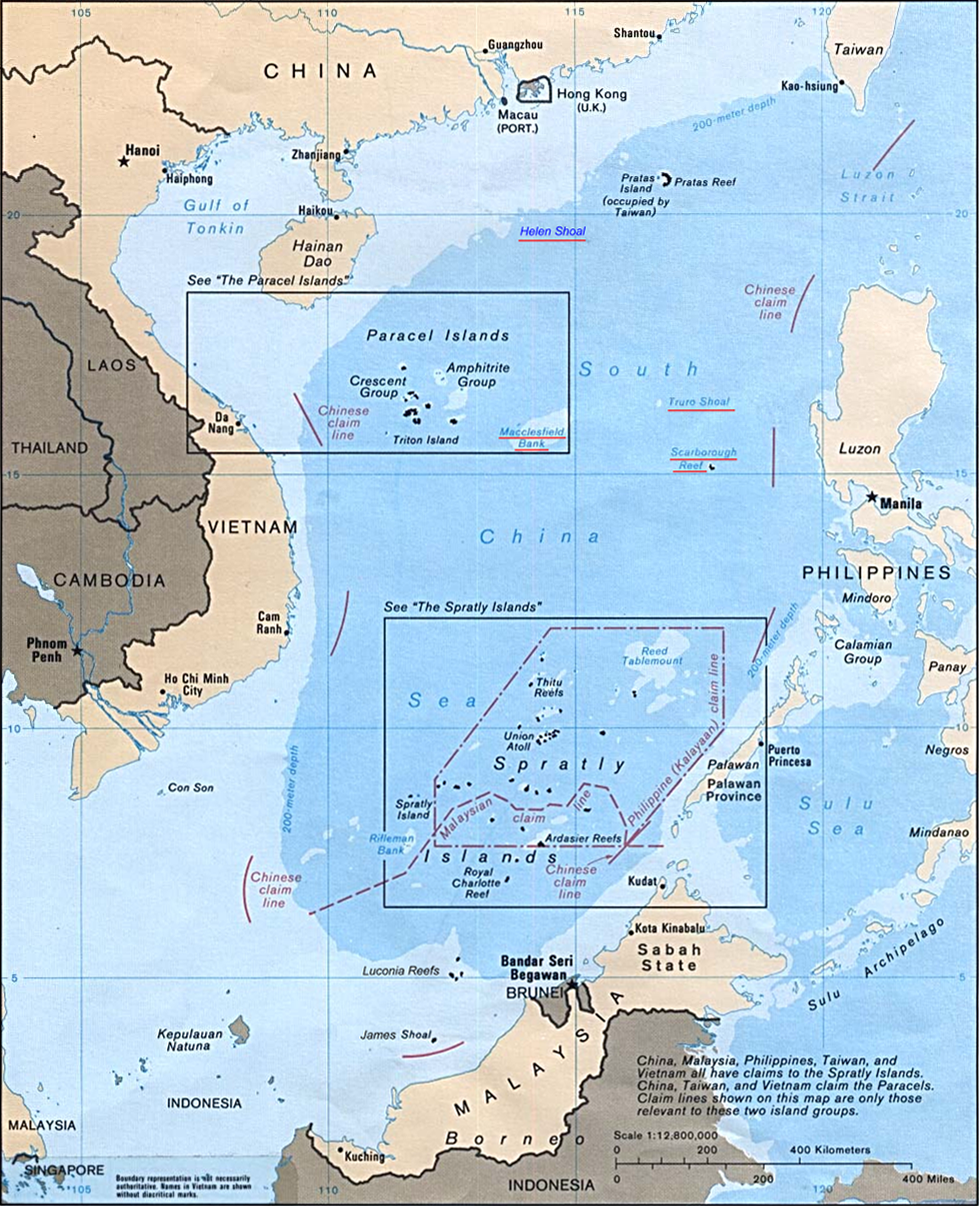

A look at a map of Asia Pacific, and one sees that it is a region dominated by bodies of water. Namely there is the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, the Andaman Sea, the Philippines Sea, the South China Sea and numerous gulfs, bays, straits and smaller seas.

Several nations are in fact described as “island nations.” Commerce by sea between and beyond Asian nations factors in as an important geopolitical and economic issue each nation must face. There is also fishing as well as gas and oil extraction performed throughout Asia’s waters.

It is no surprise then that across Asia, many disputes surface between nations regarding the use of Asia’s waters. Unlike on land, enforcing borders and perceived claims across seas and oceans is infinitely more difficult. Despite this, Asian states have resolved these issues through bilateral resolutions both for individual cases and in a more general sense. Very rarely do these disputes escalate toward serious or enduring confrontations, and more rarely still do they result in actual conflicts.

If an external force sought to destabilize Asia, it would likely seek several vectors including fostering confrontations over the use of Asia’s waters.

The United States in particular, has cultivated a multinational, multifaceted confrontation in the South China Sea for this very purpose, attempting to pit nations like Vietnam, Indonesia, the Philippines and even nations removed from the sea, all against China. Minor, isolated disputes that could otherwise be resolved through bilateral relations directly with Beijing, have now been consolidated into a larger and growing confrontation prodded forward by the involvement of the United States, its military forces and its attempts to involve international institutions.

By doing so, Asia is being destabilized. The vast majority of Asia’s economic activity unfolds within Asia itself. While exports and imports from beyond Asia are no doubt important as well, instability in Asia would be a threat to nation security and undermine economic stability for each respective state, whether they were directly involved in the South China Sea row or not.

For this purpose, Asia must resolve itself to settling disputes regarding the use and exploitation of Asia’s waters bilaterally between nations before such disputes evolve into confrontations or conflicts. External forces seeking to escalate tensions and exploit them geopolitically must be removed from the region through a series sanctions by both individual nations, and by the region collectively.

When the Philippines drastically changed tack from a growing confrontation between Manila and Beijing driven by US military and political actions, and toward bilateral negotiations between Manila and Beijing (excluding the United States), regional stability breathed a marked sign of relief.

The New York Times in an article titled, “Rodrigo Duterte and Xi Jinping Agree to Reopen South China Sea Talks,” would note:

President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines and China’s leader, Xi Jinping, agreed on Thursday to resume direct talks on disputes in the South China Sea after years of escalating tension, a sign of warming relations with Beijing.

The announcement came during Mr. Duterte’s state visit to China, as he repeatedly sought to distance the Philippines from the United States, a treaty ally. Mr. Duterte, speaking to business leaders shortly after meeting with Mr. Xi, openly declared a “separation from the United States.”

Economically and politically, Asia was to gain nothing, and perhaps lose everything had the US-backed confrontation continued to spiral out of control. While it is unlikely that the Philippines will immediately “separate” from the US, Manila’s actions to discard a policy of confrontation for one of bilateral communications with Beijing certainly diminished US influence in the region.

A Balance of Power

Within Asia, to ensure one nation does not find itself exercising unwarranted power and influence over another, a balance of power must be established through a commitment by all nations to develop strong economies, formidable armed forces and skillful diplomatic corps so that it is easier for feuding parties to make equitable concessions than to escalate toward confrontations and conflict.

For China, emerging as both a regional and global power, it is incumbent upon Beijing to avoid overreaching and thus encouraging its neighbors to seek out external powers for support and the instability they bring with them. America’s military presence across the Asia Pacific region is today predicated on “underwriting security” in the region and advertised as a means of keeping Beijing in check. A Beijing openly willing to pursue equitable bilateral resolutions with other nations in the region regarding use of its waters creates an Asia the US has no justification for keeping its military in.

In the short-term, individual Asian states may see an opportunity to gain from US-backing amid disputes throughout Asia’s waters, however the instability that will result when such disputes inevitably escalate, will cost all of Asia its collective stability and as a result, its collective prosperity.

Ulson Gunnar, a New York-based geopolitical analyst and writer especially for the online magazine “New Eastern Outlook”.

http://journal-neo.org/2016/10/27/avoiding-conflict-in-asia-pacifics-waters/