At Home and Abroad, Trump Tramples Human Rights

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

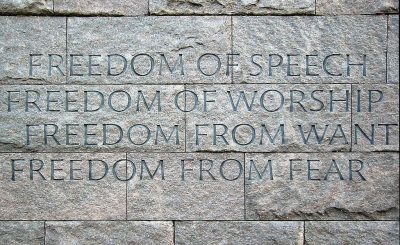

In January 1941, with the prospect looming of US involvement in another European war, President Franklin Roosevelt spoke of America’s purpose in the world: to protect and promote “four freedoms.” FDR drew a clear link between US security and the fulfillment of human rights at home. “Just as our national policy in internal affairs has been based upon a decent respect for the rights and the dignity of all of our fellow men within our gates, so our national policy in foreign affairs has been based on a decent respect for the rights and the dignity of all nations, large and small.”

In another speech he underscored the point:

“unless there is [human] security here at home there cannot be lasting peace in the world.”

Among the extraordinary backward steps Donald Trump is taking to transform America, none is more shameful than his calculated trampling on human rights at home and abroad. To my mind, the two are interrelated: A government that does not respect the human rights of its own citizens will also show no respect for human rights in other countries—and will work with other governments that seek to repress their citizens’ rights. Moreover, a government that fails to promote human rights in its own backyard will lack credibility should it criticize others’ repression of human rights.

Undermining Rights at Home

On the home front, two recent surveys show how the US has declined as a repository of human rights, in particular adherence to political rights and civil liberties. These are the World Justice Project’s Rule of Law Index, whose ranking is based on 44 indicators of lawfulness; and Freedom House, which makes annual assessments based on implementation (not claims) of rights enumerated in the 1948 UN Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The WJP ranks the US 19th of 113 countries in its 2018 survey. Among the weakest dimensions for the US are labor rights, an effective correctional system, discrimination, respect for due process, and accessibility and affordability of the legal system. For comparison sake, note that Germany (6th), Canada (9th), and Britain (11th) all rank higher than the US. Freedom House ranks the US 86th of 100 countries (100 being “most free”); Canada (99), Germany (94), and Britain (94) again rank higher. Trump’s corruption, evasion of legal and institutional norms, and low regard for certain human rights help account for a lower Freedom House ranking of the US than in previous years. The US ranked 90th in the 2016 report, for instance.

On the human-security side, a recent report by Philip Alston, the UN special rapporteur for extreme poverty and human rights, documented growing problems of poverty in America. Before Trump, the rich-poor gap was already wide and the number of people, especially children, living in poverty was pitifully large. In Alston’s view, Trump’s policies amount to “a systematic attack on America’s welfare program that is undermining the social safety net for those who can’t cope on their own. Once you start removing any sense of government commitment, you quickly move into cruelty” (see here). Nearly 23 million people, according to Alston, are living in extreme or absolute poverty. And the US has the highest rate of infant mortality, the highest rate of youth poverty, and the highest income inequality among all rich countries. Poor people are especially vulnerable in the Trump era because they are being deliberately targeted for political advantage, while a sliver of the US population benefits more than ever from tax cuts, subsidization of the fossil fuel industry, and voter restrictions.

Human security and basic human rights are under assault in other ways: by reducing government responsibility for the health and welfare system; putting energy interests and private profit ahead of action to address climate change and respect for scientific findings; subjecting immigration policy to outright racist priorities, such as by denial of due process, separation of families, and blatant disregard for the rights of children (the US is the only country in the world that has not ratified the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child); moving away from support of public education; and undermining the right of labor to organize. The Supreme Court, now with a far right-leaning majority that will soon be further strengthened by a new Trump appointee, is a handmaiden of his attack on labor unions, women’s, gay people’s, and immigrants’ rights.

Trump’s immigration policy is especially troubling. UN human rights special rapporteurs from various countries have condemned it, pointing out that his Muslim ban and rejection of legitimate asylum requests based on “a well-founded fear of persecution” violate international and US law and conventions. (A US district judge on July 3, 2018 slammed the administration for violating its own regulations on asylum seekers, and ordered that these detainees be either freed from detention or granted asylum.) Trump’s executive order of June 20, 2018, said these UN experts, “does not address the situation of those children who have already been pulled away from their parents. We call on the Government of the US to release these children from immigration detention and to reunite them with their families based on the best interests of the child, and the rights of the child to liberty and family unity. Detention of children is punitive, severely hampers their development, and in some cases may amount to torture. Children are being used as a deterrent to irregular migration, which is unacceptable” (see here).

“State-sanctioned child abuse” is the way Congressman Tim Ryan (D-OH) put it on MSNBC on July 5 in light of the separation of some 3,000 children from their parents at the US-Mexico border.

Of course such criticism will not move a president who touts “America first” and believes a harsh immigration policy is the key to his reelection.

He has already withdrawn the US from the UN Human Rights Council and rejected the critique of poverty in America by the special rapporteur, with US ambassador to the UN Nikki Haley deriding it as “patently ridiculous.” These actions, along with reduced US contributions to the UN budget, put the US on China’s and Russia’s side. Beijing and Moscow likewise want to force major reductions in the human-security side of the UN budget, including peacekeeping missions and protection of women and children from sexual exploitation (see here).

Dancing with Dictators

Meantime, the Trump administration has continued the sordid US practice of supporting authoritarian regimes, making the US party to repression of human rights abroad and, on occasion, a collaborator in crimes against humanity and war crimes. The usual pretext for such support is to maintain “stability,” counter terrorism, or align against some other equally authoritarian regime. Vietnam reflects the latter case: Washington, backing Vietnam’s territorial case against China, hasn’t said a word about repression of dissent and trials of human-rights activists there (see here). “Support” often takes the form of selling arms, as in the cases of Turkey despite widespread repression and the dismantling of democratic institutions, Saudi Arabia in its bombing campaign in Yemen (see here), and the Philippines despite its unrestrained drug war.

Israel should be added to this list, since the far-right Netanyahu government receives about $1.5 billion annually in US arms that give it license to violently suppress Palestinian protests. Not surprisingly, the equally far-right US ambassador to Israel has said Israel should be exempt from US law that requires a State Department report on whether or not US-supplied weapons are being used to repress human rights (see here).

“Israel is a democracy whose army does not engage in gross violations of human rights,” Ambassador David Friedman said.

Evidently, neither he nor the administration he serves regards attacks on Gaza demonstrators this past spring, which killed at least 135 Palestinians and wounded perhaps 15,000, as “gross violations” (see here).

Even when serious violations of human rights are occurring in adversarial countries that have something to benefit Trump, such as China, North Korea, and Russia, expect very little comment from him. Yes, he said he had brought up human rights when he met with Kim Jong-un, and insisted that US missile attacks in response to Assad’s use of chemical weapons were motivated by concern about Syrian children. But does anyone take those assertions seriously in light of his undermining of human rights at home? After all, Trump has publicly excused Kim, Xi Jinping, Putin, and other authoritarian leaders he has called great friends for their bad behavior, noting that they have a tough job and that there are “bad guys” in all political systems. Trump’s beef with China is mainly about trade and the South China Sea; human rights has yet to get a hearing. And how about Russia? While several of Trump’s top officials have criticized Putin over arbitrary arrests and even assassinations of critics, Trump has been silent. (Remember how he ignored the advice of his national security council—“Do Not Congratulate”—when he telephoned Putin on his reelection?) Or Poland, Hungary, and Turkey, where Trump-like leaders are busy burying democracy while the European Union looks on, aghast but powerless?

Trump reserves his professed concern about human rights for antagonistic rivals, notably Cuba and Iran—the very countries, not coincidentally, that Obama successfully engaged. Those countries are important either because of their domestic political value (Cuba) or (for Iran) because of Trump’s ties to Israel and Saudi Arabia. But aligning against Cuba and Iran only worsens human rights conditions in those countries. In a word, the more antagonistic US policy becomes—imposing sanctions and promoting regime change—the more are human rights threatened, first because of their often devastating impact on ordinary people’s lives, and second because hard-line elements in Cuba and Iran have ammunition to increase repression in the name of national security. (For example, in Iran: see here).

Discussion of sensitive human-rights cases often gets relegated to the annual state department report on conditions around the world, a report required by Congress. Even here the Trump administration has downplayed human rights. When the 2016 report was prepared, former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson rejected the usual practice of presenting it to the press, evidently to discount its importance (see here). The 2017 report, which came out this April, “sugarcoated” several controversial issues, as one human rights NGO leader put it. These deceptions include Israel’s conduct in the Occupied Territories (no longer labeled as such), high civilian casualties from Saudi Arabia’s indiscriminate bombing in Yemen (referred to as “disproportionate collateral damage”), and women’s reproductive rights (no longer mentioned). (See here.) Little wonder that so many senior diplomats have quit over Trump’s disdain for human rights, including John Feeley as US ambassador to Panama, Elizabeth Shackelford as chief political officer in the US embassy in Somalia, and Jim Melville as ambassador to Estonia.

A Declining Example

The United States has always claimed to be an exemplar of respect for human rights—for liberty, democracy, and the rule of law—and has deplored (and occasionally sanctioned) outrageous human conditions in some other countries. That stance was the foundation of Roosevelt’s argument for US entry into World War II—as well of Eleanor Roosevelt’s role in crafting the UN Universal Declaration. Every postwar US administration since has had a very inconsistent record in that regard, but Trump’s is the worst of the lot by far: He rarely even makes reference to human rights, much less takes action on its behalf. But then again, any action he might take would lack credibility, because as FDR observed, improving human rights at home is central to protecting it abroad.

Trump does not make that connection. He is riveted on two things, money and power, the core concerns of a big businessman who never has enough. The lure of money hardly needs explanation. First come the receipts: Trump and his family see gold in foreign officials’ visits to his US and overseas properties, in potential hotel and golf sites for his brand, and in (secret) transfers of funds to support his election and help pay his debts. Then there are the costs: Trump has declared that certain military exercises, alliances (read: NATO, Japan, and South Korea, among others), and overseas bases are too expensive. Human rights concerns do not figure in such a bottom-line calculus (see here).

Trump’s aim to expand his personal power may be seen in his affection for certain autocrats. Democracy, the rule of law, and transparency are among the least interests to this president. Trump looks for inspiration to dictators because they display the kind of raw, unchallenged political power he would like to have—the power, that is, to defy behavioral. policy and legal norms, behave brutally with those who are disloyal or disagree, and go it alone without consequences. Granted, talking with dictators is sometimes necessary and useful, especially if there is a deal in the works. The Singapore summit with Kim Jong-un is a prime example. But admiring dictators is another matter entirely: It betrays a disturbing personal characteristic of Trump’s.

We see the dictator’s playbook at work in Trump’s stance on immigration—a direct appeal to popular fears and long-denied racist impulses. Paul Krugman contends here that Trump must stir up unreasoning hatred of “the other.” Krugman writes: “the atrocities our nation is now committing at the border don’t represent an overreaction or poorly implemented response to some actual problem that needs solving. There is no immigration crisis; there is no crisis of immigrant crime. No, the real crisis is an upsurge in hatred — unreasoning hatred that bears no relationship to anything the victims have done. And anyone making excuses for that hatred — who tries, for example, to turn it into a ‘both sides’ story — is, in effect, an apologist for crimes against humanity.”

And now the US Supreme Court, far from helping stem this tide, has endorsed a president’s power to claim a national security threat that will keep Muslims out of America. The founders of this country, who looked for it to be a “shining example” to the world, must be turning over in their graves. So, surely, is FDR.

*

Mel Gurtov is Professor Emeritus of Political Science at Portland State University, Senior Editor of Asian Perspective, and author most recently of Engaging Adversaries: Peacemaking and Diplomacy in the Human Interest(Rowman & Littlefield, 2018). He blogs here.

All images in this article are from the author.