Inside the Assange Plea Deal: Why the US Government Abruptly Ended the Case

US prosecutors brushed aside calls to end the case against the WikiLeaks founder—until a British appeals court granted a hearing on the First Amendment.

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Give Truth a Chance. Secure Your Access to Unchained News, Donate to Global Research.

***

For five years, the United States Justice Department defied calls from around the world to drop Espionage Act charges against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange. Prosecutors even faced pressure from the Australian government, which demanded that a close ally end the case and return one of their citizens to his home country. Yet prosecutors remained committed to putting Assange on trial.

That all changed in May after the British High Court of Justice granted Assange an extradition appeal hearing on the question of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. The Justice Department “re-engaged” Assange’s legal team and participated in “very intense” negotiations for a plea deal.

U.S. prosecutors accepted a guilty plea to one conspiracy charge under the Espionage Act, with no additional prison sentence. The plea deal did not contain a gag order, and officials agreed to Assange’s request to avoid travel to the continental United States. He was released on bail from Belmarsh prison and flew on a charter flight to a courthouse in a U.S. territory in the Pacific Ocean known as the Northern Mariana Islands.

More importantly, the Justice Department pledged not to pursue any future charges for any uncharged conduct that Assange allegedly committed prior to his guilty plea.

This abrupt shift brought a conclusion to a 14-year-long legal saga on June 26. The award-winning journalist had spent a little more than five years detained at Belmarsh prison, which is often referred to as “Britain’s Guantanamo.” Chief Judge Ramona Manglona accepted the plea deal and sentenced Assange to time served.

“I do hope that there will in fact be some peace restored,” Manglona remarked. “I’ll just note, too, that this past week the island has been celebrating 80 years of peace since the Battle of Saipan. This was a very bloody place between the Japanese and the Americans, and the people have been celebrating the fact that we’ve been celebrating peace here with the former enemy.”

“And now, there is some peace that you need to restore with yourself when you walk out, and you pursue your life as a free man.”

Before ending the proceeding, Manglona added,

“Mr. Assange, apparently, it’s an early happy birthday to you,” and, “It’s probably the first one that you’ll have outside of a prison or any type of limitation.” (His birthday is July 3.)

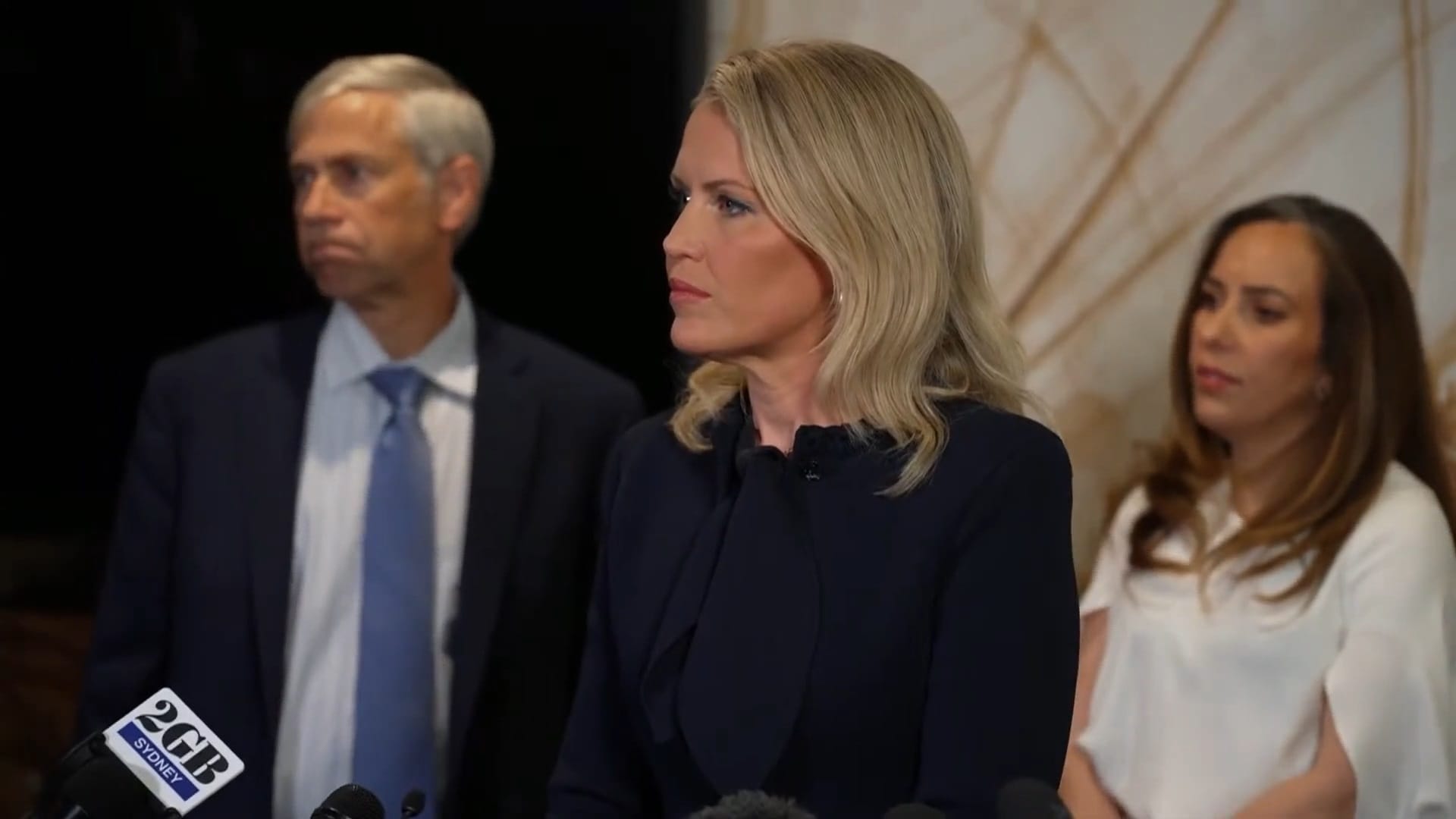

A press conference was held by Stella Assange and Assange’s legal team in Canberra after Assange landed in Australia. While Assange was not at the press conference, his attorneys revealed key details about the nature of the plea agreement and the legal and political factors that helped end this multi-year long prosecution and extradition case.

The US Came Back to the Table After the Appeal Hearing Was Granted

Justice Department prosecutors were not truly motivated to come to a plea agreement with Assange until weeks ago, after the High Court in London granted Assange the right to appeal his extradition.

“[T]he negotiations were a protracted process that went on for several months, sort of in fits and starts,” explained Assange’s U.S. lawyer Barry Pollack. “We were not close to any sort of a resolution until a few weeks ago, when the Department of Justice re-engaged and there have been very intense negotiations over the last few weeks.”

This point was also emphasized by Stella Assange, who said it was “important to recognize that Julian’s release and the breakthrough in negotiations came at a time when there had been a breakthrough in the legal case, in the U.K.” The High Court had “allowed permission to appeal. There was a court date set for the 9-10 of July….in which Julian would be able to raise the First Amendment argument at the High Court.”

“It is in this context that things finally started to move,” Stella declared.

Assange was granted the right to appeal his extradition to the U.S. on the basis that it was at least arguable that he would be prejudiced at trial by reason of his nationality and citizenship. The U.K. Extradition Act 2003 prohibits extradition to a country where a person may be prejudiced at trial by reason of their nationality.

Assistant U.S. Attorney Gordon Kromberg, a lead prosecutor in the case, told the courts that the U.S. government might argue during trial proceedings that Assange was not protected by the First Amendment.

“[Kromberg] made a formal sworn declaration on behalf of the respondent and in support of the extradition request,” the High Court stated in its judgment of March 26. “He put himself forward as able to provide authoritative assistance as to the application of the First Amendment. It can fairly be assumed that he would not have said that the prosecution ‘could argue that foreign nationals are not entitled to protections under the First Amendment’ unless that was a tenable argument that the prosecution was entitled to deploy with a real prospect of success.”

“If such an argument were to succeed it would (at least arguably) cause the applicant prejudice on the grounds of his non-US citizenship (and hence, on the grounds of his nationality),” the court added.

The U.S. government deployed their hubristic argument about Assange and the First Amendment as part of their defense of the extradition request—and it backfired.

Marjorie Cohn, the dean of the People’s Academy of International law and former president of the National Lawyers Guild, asserted,

“It is no coincidence that the plea came a little more than a month after the High Court of England and Wales ruled that Assange could appeal the extradition order against him. The Justice Department apparently feared it would lose the appeal.”

Stella Assange said that she believed the negotiations “revealed how uncomfortable the United States government is, in fact, [with] having these arguments aired.”

“The fact that this case is an attack on journalism, it’s an attack on the public’s right to know, and it should never have been brought,” she concluded. “Julian should never have spent a single day in prison. But today we celebrate because today Julian is free.”

US Agreed Not to Pursue Further Charges

One of the most incredible revelations regarding Assange’s plea deal is that the U.S. government “agreed that they would not bring any other charges against Julian for any conduct, any publications, any newsgathering, anything at all that occurred prior to the time of the plea,” according to Barry Pollack.

This is of particular note because, as Pollack explained, even if Assange succeeded in his appeal against extradition, that success “would have just resolved this case.”

The 18-count indictment against Assange focused almost exclusively on the WikiLeaks publisher’s role in obtaining, possessing, and publishing documents between 2009 and 2011, known as the Iraq War logs, Afghanistan War diaries, Guantanamo Bay detainee files, and diplomatic cables (Cablegate).

One criminal charge under the Computer Fraud and Abuse Act was disturbingly expanded by prosecutors to include a speech that Assange gave to a room of computer specialists during which he encouraged people to provide WikiLeaks with information which was in the public interest.

However, Assange was never charged for WikiLeaks’ role in publishing emails belonging to the Democratic National Committee—acts which even former FBI director Robert Mueller concluded were likely protected by the First Amendment.

Nor was Assange ever charged for WikiLeaks’ 2017 exposé detailing the CIA’s expansive cyberwarfare arsenal known as the Vault 7 materials. The leak and publication of files led Mike Pompeo, when he was CIA director, to reportedly obsess over targeting, kidnapping, or killing Assange in revenge.

With the plea agreement [PDF], which The Dissenter reviewed, the U.S. government cannot ever bring a case against Assange for other acts of journalism.

“The United States agrees not to bring any additional charges against the Defendant based upon conduct that occurred prior to the time of this Plea Agreement,” the plea agreement states, “unless the Defendant breaches this Plea Agreement.”

Judge Manglona said,

“I was quite surprised, but I think it’s a very generous statement.” She noted that it applied to everything for the past 14 years. “That’s very broad.”

Another key position that Assange’s legal team took during the negotiations was that “any resolution would have to end this matter,” according to Pollack. Meaning that “Julian would be free, [and that] he was not going to do any additional time in prison. He was not going to do time under supervision. He was not going to do time under a gag order.”

Political Lobbying Behind the Scenes

Australian human rights attorney Jennifer Robinson (Credit: Free Assange News)

Australian human rights attorney Jennifer Robinson, who represented Assange in the U.K., further described the strong political dimension to the case. Extensive lobbying efforts by members of the Australian government proved crucial to the overall result.

Robinson thanked Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese for his “principled leadership,” “statesmanship,” and “diplomacy.” She explained that raising opposition to Assange’s extradition at the “highest levels” of the U.S. government “completely changed the situation for Julian” and “enabled our negotiations with the U.S. government that allowed us to reach this outcome.”

The prime minister was under intense and growing pressure from the wider public, parts of the press, and an increasing number of Australian members of parliament.

Robinson credited Kevin Rudd, who is Australia’s Ambassador to the US and a former Australian prime minister, as well as Steven Smith, who is Australia’s High Commissioner to the U.K., and the consular staff in London. Smith accompanied Assange on his flight from London to Saipan.

She explained that Rudd’s “relentless efforts in Washington working together, closely with us—with myself and my co-counsel Barry Pollack, completely changed our relationship with the U.S. and completely changed the negotiations. Without his efforts and his adept diplomacy, we would not be in the position we are today. And Julian would not be home.”

Speaking to the Australia Broadcasting Corporation on June 27, Robinson explained that once Ambassador Rudd was sent to Washington D.C. the U.S. Department of Justice finally started to deal with the defense team in a meaningful way.

“That opened up conversations for us with the Department of Justice that…we were trying to have and were not getting responses and so things moved.”

As many people, including Stella Assange, argued over the past few years, this was a politically motivated prosecution, and therefore it stood to reason that it would be political pressure, which would ultimately resolve the case.

The lobbying efforts of high-ranking Australian politicians and government officials would not have occurred without the intense lobbying of everyday members of the public, activists, and press freedom and human rights organizations (the latter of which were brought on board as a result of intensive upward pressure).

A number of years ago there were only a few political figures in the U.K. and Australia, who were willing to be open and clear in their opposition to Assange’s extradition. For example, people such as then-Labour MP for Derby North Chris Williamson and George Galloway, who was recently re-elected to parliament, as well as Australia’s independent MP for Clark, Tasmania Andrew Wilkie and the conservative politician George Christensen, at the time a member of House of Representatives with the National Liberal Party, for Dawson, Queensland.

“It took millions of people…people working behind the scenes, people protesting on the streets—for days and weeks and months and years,” Stella Assange told the press conference, “and we achieved it.”

Julian Assange and his legal team arrive in Canberra, Australia (Credit: Free Assange News)

Assange Required to Instruct WikiLeaks to Destroy Unpublished Files

Before Assange’s guilty plea was entered in court, the agreement with the U.S. government required him to “take all action within his control to cause the return to the United States or the destruction of any such unpublished information in his possession, custody, or control, or that of WikiLeaks or any affiliate of WikiLeaks.”

Barry Pollack confirmed that Assange had instructed WikiLeaks editor-in-chief Kristinn Hrafnsson to destroy “any materials they might have that were not published.”

WikiLeaks editor-in-chief Kristinn Hrafnsson confirmed to The Dissenter that Assange had requested that he destroy “all unpublished U.S. secret documents.”

This provision in the plea agreement echoed the infamous decision in 2013 by editors at The Guardian newspaper to take a power drill and angle grinder to a hard drive which contained copies of vast troves of information leaked by National Security Agency (NSA) whistleblower Edward Snowden to then Guardian columnist Glenn Greenwald.

Editors were threatened with legal action if they did not either hand over the hard drives. They agreed to destroy them in the basement of their headquarters in London, even though it was understood that copies existed elsewhere outside of the U.K.

Technicians from Government Communications Headquarters—the U.K equivalent of the NSA—filmed the destruction of the computer hard drive while taking notes and providing instructions to the editors.

Guardian editor Paul Johnson was among those who described the destruction as a “purely symbolic” act, since everyone involved knew that there were copies of the materials—which revealed the details of Anglo-American mass-warrantless spying and surveillance of hundreds of millions of people in the U.S. and around the world.

Yet the act was more than symbolic. It was a potent reminder of the power of the U.K. government (acting with the encouragement of the U.S. national security state), and its ability to threaten and bend even well-known and well-resourced establishment news media to its will.

As investigative journalist Kit Klarenberg recounted for The Dissenter, three years after the destruction of the hard drive, The Guardian’s investigative team “was dissolved, and Guardian coverage of military, security and intelligence issues declined precipitously. In fact, presently, many key national security correspondents at the Guardian have little background in the field.”

The US Did Not—or Could Not—Identify Any Victims

The United States government was unwilling or unable to identify any “victim” of the published leaks, and prosecutors did not request that Assange pay restitution for any alleged harm.

However, during a press briefing on June 26, State Department spokesperson Matthew Miller maintained there were “victims.”

“If you recall when WikiLeaks first disseminated and published State Department cables, they did so without redacting names,” Miller falsely asserted. “They just threw them out there for the world to see. And so the documents they published gave identifying information of individuals, who were in contact with the State Department. That included opposition leaders, human rights activists around the world whose positions were put in some danger because of their public disclosure.”

“Those of you who covered the State Department at the time will probably remember that in the days leading up to that release the State Department really had to scramble to get people out of danger, to move them out of harm’s way,” Miller said.

Miller was not at the State Department. He was working at the time as a Justice Department spokesperson in President Barack Obama’s administration, and in fact, Miller opposed the Assange prosecution before he was an official in President Joe Biden’s administration.

The entire cache of 250,000-plus diplomatic cables became available on the internet because Guardian editor David Leigh included the passphrase for an encrypted file containing the cables in a book he co-authored about working with WikiLeaks.

Assange called the State Department to warn them of the risks posed by the publication of unredacted cables.

“I appreciate that you’ve recognized that these kinds of releases absolutely can pose a threat to the very sources reflected in the material,” said Cliff Johnson, who was a legal advisor to the State Department.

Miller complained about the supposed negative impact that the release of the cables had on U.S. diplomacy. But Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said when the cables were first published,

“I’ve heard the impact of these releases on our foreign policy described as a meltdown, as a game-changer, and so on,” and, “I think those descriptions are fairly significantly overwrought.”

“The fact is, governments deal with the United States because it’s in their interest, not because they like us, not because they trust us, and not because they believe we can keep secrets.” He also said “every other government in the world knows the United States government leaks like a sieve, and it has for a long time.”

Associated Press reporter Matthew Lee was covering the State Department when WikiLeaks first published the cables. As he recalled, there was no “public concern that was raised about the potential security risks posed to sources who might have been quoted.”

Aside from the cables, the U.S. military was never able to find any evidence that the publications of military war logs from Iraq and Afghanistan resulted in any person’s death.

Pentagon Papers whistleblower Ellsberg testified at Assange’s extradition hearing in September 2020. He noted that Assange withheld 15,000 files from the release of the Afghanistan War Logs. He also requested assistance from the State Department and the Defense Department on redacting names, but they refused to help WikiLeaks redact a single document, even though it is a standard journalistic practice to consult officials to minimize harm.

“I have no doubt that Julian would have removed those names,” Ellsberg declared. Both the Pentagon and State Department could have helped WikiLeaks remove the names of individuals.Rather than take steps to protect individuals, Ellsberg suggested U.S. officials chose to “preserve the possibility of charging Mr Assange with precisely the charges” that he faced.

Assange Stated in Court That He Committed Journalism

The U.S. government may have accepted a plea deal that showed Assange some mercy, but they still coerced, or forced, the WikiLeaks founder to plead guilty to journalism if he wanted to obtain his freedom.

At the court hearing in Saipan, Judge Manglona asked Assange to describe what he did that constituted “the crime charged.”

“Working as a journalist, I encouraged my source to provide information that was said to be classified in order to publish that information. I believe that the First Amendment protected that activity, but I accept that as written it’s a violation of the Espionage Act statute.”

“So you had [a] certain belief, but you understand what the law actually says as well?” Manglona replied.

Assange told the judge,

“I believe the First Amendment and the Espionage Act are in contradiction with each other, but I accept that it would be difficult to win such a case given all the circumstances.”

Essentially, Assange recalled an act that reporters at numerous media outlets commit routinely, and the judge accepted that as a “crime.”

Matthew McKenzie, deputy chief for the counterintelligence and export control section in the U.S. Justice Department’s national security division, emphasized that the U.S. government rejects Assange’s contention that his conduct should be protected by the First Amendment.

The U.S. Justice Department could have celebrated the end of this legal saga and spun it as a victory. But prosecutors put out an announcement that contained no statements from Attorney General Merrick Garland, the U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia, or any prosecutors who were involved in the case. It contained a closing argument that one might hear before the jury deliberated over a verdict, but no proclamations of victory.

Stephen Rohde, a constitutional scholar and former chair of the ACLU Foundation of Southern California, said,

“When U.S. prosecutors had to put up or shut up to satisfy the High Court that Assange’s right to freedom of expression would be protected if he was extradited, they blinked. An Assange trial posed grave risks that the U.S. would be embarrassed by revelations that the CIA had plotted to kidnap or assassinate him.”

The case ended in a whimper for the U.S. government. In contrast, Assange and his legal team were mindful of the damage to press freedom but jubilant that one of the most well-known political prisoners in the world was free.

And for journalists and media organizations around the world, it was a bittersweet outcome.

Like Jennifer Robinson explained at the press conference, the plea agreement has no impact on legal precedent. It is the prosecution itself which set the precedent that media professionals anywhere in the world can face prosecution by the U.S., under a law with no public interest defense, for the crime of journalism.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Featured image is from The Dissenter