Assange Final Appeal – Your Man in the Public Gallery. Craig Murray

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name (only available in desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Big Tech’s Effort to Silence Truth-tellers: Global Research Online Referral Campaign

***

Reporting on Julian Assange’s extradition hearings has become a vocation that has now stretched over five years. From the very first hearing, when Justice Snow called Assange “a narcissist” before Julian had said anything whatsoever other than to confirm his name, to the last, when Judge Swift had simply in 2.5 pages of glib double-spaced A4 dismissed a tightly worded 152-page appeal from some of the best lawyers on earth, it has been a travesty and charade marked by undisguised institutional hostility.

We were now on last orders in the last chance saloon, as we waited outside the Royal Courts of Justice for the appeal for a right of final appeal.

The architecture of the Royal Courts of Justice was the great last gasp of the Gothic revival; having exhausted the exuberance that gave us the beauty of St Pancras Station and the Palace of Westminster, the movement played out its dreary last efforts at whimsy in shades of grey and brown, valuing scale over proportion and mistaking massive for medieval. As intended, the buildings are a manifestation of the power of the state; as not intended, they are also an indication of the stupidity of large scale power.

Court number 5 had been allocated for this hearing. It is one of the smallest courts in the building. Its largest dimension is its height. It is very high, and lit by heavy mock medieval chandeliers hung by long cast iron chains from a ceiling so high you can’t really see it. You expect Robin Hood to suddenly leap from the gallery and swing across on the chandelier above you. The room is very gloomy; the murky dusk hovers menacingly above the lights like a miasma of despair; below them you peer through the weak light to make out the participants.

A huge tiered walnut dais occupies half the room, with the judges seated at its apex, their clerks at the next level down, and lower lateral wings reaching out, at one side housing journalists and at the other a huge dock for the prisoner or prisoners, with a massy iron cage that looks left over from a production of The Hunchback of Notre Dame.

This is in fact the most modern part of the construction; caging defendants in medieval style is a Blair era introduction to the so-called process of law.

Rather incongruously, the clerks’ tier was replete with computer hardware, with one of the two clerks operating behind three different computer monitors and various bulky desktop computers, with heavy cables twisting in all directions like sea kraits making love. The computer system seems to bring the court into the 1980’s, and the clerk behind it looked uncannily like a member of a synthesiser group of that era, right down to the upwards pointing haircut.

In period keeping, this computer feed to an overflow room did not really work, which led to a number of halts in proceedings.

All the walls are lined with high bookcases, housing thousands of leather bound volumes of old cases. The stone floor peeks out for one yard between the judicial dais and the storied wooden pews, with six tiers of increasingly narrow seating. The barristers occupied the first tier and their instructing solicitors the second, with their respective clients on the third. Up to ten people per line could squeeze in, with no barriers on the bench between opposing parties, so the Assange family was squashed up against the CIA, State Department and UK Home Office representatives.

That left three tiers for media and public, about thirty people. There was however a wooden gallery above which housed perhaps twenty more. With little fuss and with genuine helpfulness and politeness, the court staff – who from the Clerk of Court down were magnificent – had sorted out the hundreds of those trying to get in, and we had the UN Special Rapporteur on Torture, we had 16 Members of the European Parliament, we had MPs from several states, we had NGOs including Reporter Without Borders, we had the Haldane Society of Socialist Lawyers, and we had, (checks notes) me, all inside the Court.

I should say this was achieved despite the extreme of official unhelpfulness from the Ministry of Justice, who had refused official admission and recognition to all of the above, including the United Nations. It was pulled together on the day by the police, court staff and the magnificent Assange volunteers led by Jamie. I should also acknowledge Jim, who with others spared me the queue all night in the street which I had undertaken at the International Court of Justice, by volunteering to do it for me.

This sketch captures the tiny non-judicial portion of the court brilliantly. Paranoid and irrational regulations prevent publication of photos or screenshots.

My rough sketch while trying to listen on a difficult audio feed.

At front two Counsels for #Assange, to right behind them Gareth Perice, then from right John Shipton, @GabrielShipton, @Stella_Assange, behind them @ChrisLynnHedges. Also saw @CraigMurrayOrg and @suigenerisjen. pic.twitter.com/pNI2mHMRHW

— Matt Ó Branáin (@MattOBranain) February 20, 2024

The acoustics of the court are simply terrible. We are all behind the barristers as they stood addressing the judges, and their voices were at the same time muffled yet echoing from the bare stone walls.

I did not enter with a great deal of hope. As I have explained in How the Establishment Functions, judges do not have to be told what decision is expected by the Establishment. They inhabit the same social milieu as ministers, belong to the same institutions, attend the same schools, go to the same functions.

The United States’ appeal against the original blocking of Assange’s extradition was granted by a Lord Chief Justice who is the former room-mate, and still best friend, of the minister who organised the removal of Julian from the Ecuadorean Embassy.

The blocking of Assange’s appeal was done by Judge Swift, a judge who used to represent the security services, and said they were his favourite clients. In the subsequent Graham Phillips case, where Mr Phillips was suing the Foreign Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) for sanctions being imposed upon him without any legal case made against him, Swift actually met FCDO officials – one of the parties to the case – and discussed matters relating to it privately with them before giving judgment. He did not tell the defence he had done this. They found out, and Swift was forced to recuse himself.

Personally I am surprised Swift is not in jail, let alone still a High Court judge. But then what do I know of justice?

The Establishment politico-legal nexus was on even more flagrant display today. Presiding was Dame Victoria Sharp, whose brother Richard had arranged an £800,000 loan for then Prime Minister Boris Johnson and immediately been appointed Chairman of the BBC, (the UK’s state propaganda organ). Assisting her was Justice Jeremy Johnson, another former barrister representing MI6.

By an amazing coincidence, Justice Johnson had been brought in seamlessly to replace his fellow ex-MI6 hiree Justice Swift, and find for the FCDO in the Graham Phillips case!

And here these two were now to judge Julian!

What a lovely, cosy club is the Establishment! How ordered and predictable! We must bow down in awe at its majesty and near divine operation. Or go to jail.

Well, Julian is in jail, and we stood ready for his final shot for an appeal. We all stood up and Dame Victoria took her place. In the murky permanent twilight of the courtroom, her face was illuminated from below by the comparatively bright light of a computer monitor. It gave her a grey, spectral appearance, and the texture and colour of her hair merged into the judicial wig seamlessly. She seems to hover over us as a disturbingly ethereal presence.

Her colleague, Justice Johnson, for some reason was positioned as far to her right as physically possible. When they wished to confer he had to get up and walk. The lighting arrangements did not appear to cater for his presence at all, and at times he merged into the wall behind him.

Dame Victoria opened by stating that the court had given Julian permission to attend in person or to follow on video, but he was too unwell to do either. After that disturbing news, Edward Fitzgerald KC rose to open the case for the defence to be allowed an appeal.

There is a crumpled magnificence about Mr Fitzgerald. He speaks with great authority and a moral certainty that compels belief. At the same time he appears so large and well-meaning, so absent of vanity or pretence, that it is like watching Paddington Bear in a legal gown. He is a walking caricature of Edward Fitzgerald.

Barristers’ wigs have tight rolls of horsehair stuck to a mesh that stretches over the head. In Mr Fitzgerald’s case, the mesh has to be stretched so far to cover his enormous brain, that the rolls are pulled apart, and dot his head like hair curlers on a landlady.

Fitzgerald opened with a brief headline summary of what the defence would argue, in identifying legal errors by Judge Swift and Magistrate Baraitser, that meant an appeal was viable and should be heard.

Firstly, extradition for a political offence was explicitly excluded under the UK/US Extradition Treaty which was the basis for the proposed extradition. The charge of espionage was a pure political offence, recognised as such by all legal authorities, and Wikileaks’ publications had been to a political end, and even resulted in political change, so were protected speech.

Baraitser and Swift were wrong to argue that the Extradition Treaty was not incorporated in UK domestic law and therefore “not justiciable”, because extradition against its terms engaged Article V of the European Convention (on Human Rights on Abuse of Process) and Article X (on Freedom of Speech).

The Wikileaks revelations had revealed serious state illegality by the government of the United States, up to and including war crimes. It was therefore protected speech.

Article III and Article VII of the ECHR were also engaged because in 2010 Assange could not possibly have predicted a prosecution under the Espionage Act, as this had never been done before despite a long history in the USA of reporters publishing classified information in national security journalism. The “offence” was therefore unforeseeable. Assange was being “Prosecuted for engaging in the normal journalistic practice of obtaining and publishing classified information”.

The possible punishment in the United States was entirely disproportionate, with a total possible jail sentence of 175 years for those “offences” charged so far.

Assange faced discrimination on grounds of nationality, which would make extradition unlawful. US authorities had declared he would not be entitled to First Amendment protection in the United States because he is not a US citizen.

There was no guarantee further charges would not be brought more serious than those which had already been laid, in particular with regard to the Vault 7 publication of CIA secret technological spying techniques. In this regard, the United States had not provided assurances the death penalty could not be invoked.

The CIA had made plans to kidnap, drug and even to kill Mr Assange. This had been made plain by the testimony of Protected Witness 2 and confirmed by the extensive Yahoo News publication. Therefore Assange would be delivered to authorities who could not be trusted not to take extrajudicial action against him.

Finally, the Home Secretary had failed to take into account all these due factors in approving the extradition.

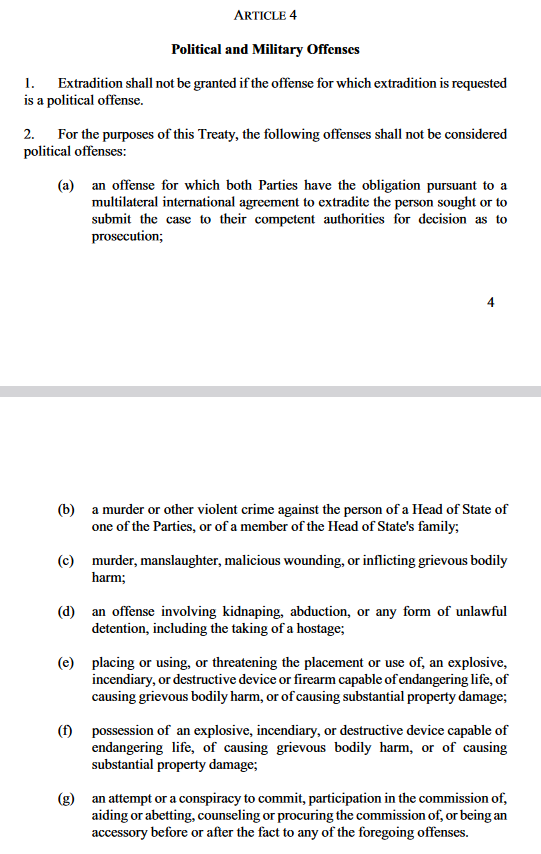

Fitzgerald then moved into the unfolding of each of these arguments, opening with the fact that the US/UK Extradition Treaty specifically excludes extradition for political offences, at Article IV.

Fitzgerald said that espionage was the “quintessential” political offence, acknowledged as such in every textbook and precedent. The court did have jurisdiction over this point because ignoring the provisions of the treaty rendered the court liable to accusations of abuse of process.

He noted that neither Swift nor Baraitser had made any judgment on whether or not the offences charged were political, relying on the argument the treaty did not apply anyway.

But the entire extradition depended on the treaty. It was made under the treaty. “You cannot rely on the treaty, and then refute it”.

This point brought the first overt reaction from the judges, as they looked at each other to wordlessly communicate what they had made of it. It was a point of which they had felt the force.

Fitzgerald continued that when the 2003 Extradition Act, on which the Treaty depended, had been presented to Parliament, ministers had assured parliament that people would not be extradited for political offences. Baraitser and Swift had said that the 2003 Act had deliberately not had a clause forbidding extradition for political offences. Fitzgerald said you could not draw that inference from an absence. There was nothing in the text permitting extradition for political offences. It was silent on the point.

Nothing in the Act precluded the court from determining that an extradition contrary to the terms of the treaty under which the extradition was taking place, would be a breach of process. In the United States, there had been cases where extradition to the UK under the treaty had been prevented by the courts because of the ‘no political extradition’ clause. That must apply at both ends.

Of the UK’s 158 extradition treaties, 156 contained a ban on extradition for political offences. This was plainly systematic and entrenched policy. It could not be meaningless in all these treaties. Furthermore this was the opposite of a novel argument. There were a great many authoritative cases, stretching back centuries, in the UK, US, Ireland, Canada, Australia and many other countries in which “no political extradition” was firmly established jurisprudence. It could not suddenly be “not justiciable”.

It was not only justiciable, it had been very extensively adjudicated.

All of the offences charged were as “espionage” except for one. That “hacking” charge, of helping Chelsea Manning in receiving classified documents, even if it were true, was plainly a similar allegation of a form of espionage activity.

The indictment describes Wikileaks as a “non-state hostile intelligence agency”. That was plainly an accusation of espionage. This is self-evidently a politically motivated prosecution for a political offence.

Julian Assange is a person in political conflict with the view of the United States, who seeks to affect the policies and operations of the US government.

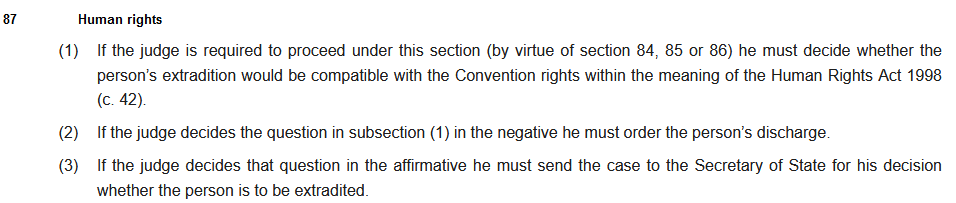

Section 87 of the Extradition Act 2003 provides that a court must interpret it in the light of the defendant’s human rights as enshrined in the European Convention of Human Rights. This definitely brings in the jurisdiction of the court. It means all the issues raised must be viewed through the prism of the ECHR and from no other angle.

To depend on the treaty yet ignore its terms is abuse of process and contrary to the ECHR. The obligation in UK law to respect the terms of the extradition treaty with the USA while administering an extradition under it, was comparable to the obligation courts had found to follow the Modern Slavery Convention and Refugee Convention.

Mark Summers KC then arose to continue the case for Assange. A dark and pugnacious character, he could be well cast as Heathcliff. Summers is as blunt and direct as Fitzgerald is courteous. His points are not so much hammered home, as piledriven.

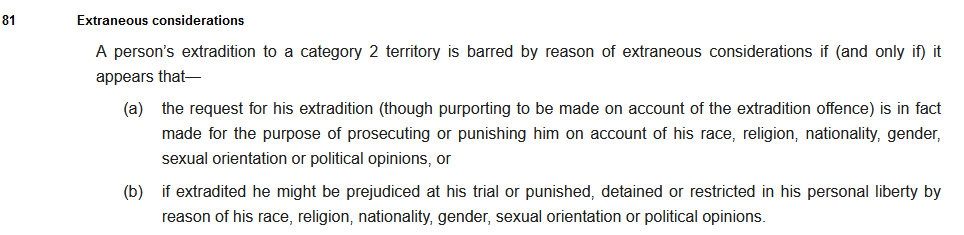

This prosecution, Summers began, was “intended to prohibit and punish the exposure of state level crime”. The extradition hearing had heard unchallenged evidence of this from many witnesses. The speech in question was thus protected speech. This extradition was not only contrary to the US/UK Extradition Treaty of 2007, it was also plainly contrary to Section 81 of the Extradition Act of 2003.

This prosecution was motivated by a desire to punish and suppress political opinion, contrary to the Act. It could be shown plainly to be a political prosecution. It had not been brought until years after the proposed offence; the initiation of the charges had been motivated by the International Criminal Court stating that they were using the Wikileaks publications as evidence of war crimes. That had been immediately followed by US government denunciation of Wikileaks and Assange, by the designation as a non-state hostile intelligence agency, and even by the official plot to kidnap, poison, rendition or assassinate Assange. That had all been sanctioned by President Trump.

This prosecution therefore plainly bore all of the hallmarks of political persecution.

The magistrates’ court had heard unchallenged evidence that the Wikileaks material from Chelsea Manning contained evidence of assassination, rendition, torture, dark prisons and drone killings by the United States. The leaked material had in fact been relied on with success in legal actions in many foreign courts and in Strasbourg itself.

The disclosures were political because the avowed intention was to effect political change. Indeed they had caused political change, for example in the Rules of Engagement for forces in Iraq and Afghanistan and in ending drone killings in Pakistan. Assange had been highly politically acclaimed at the time of the publications. He had been invited to address both the EU and the UN.

The US government had made no response to any of the extensive evidence of United States state level criminality given in the hearing. Yet Judge Baraitser had totally ignored all of it in her ruling. She had not referred to United States criminality at all.

At this point Judge Sharp interrupted to ask where they would find references to these acts of criminality in the evidence, and Summers gave some very terse pointers, through clenched teeth.

Summers continued that in law it is axiomatic that the exposure of state level criminality is a political act. This was protected speech. There were an enormous number of cases across many jurisdictions which indicate this. The criminality presented in this appeal was tolerated and even approved by the very highest levels of the United States government. Publication of this evidence by Mr Assange, absent any financial motive for him to do so, was the very definition of a political act. He was involved, beyond dispute, in opposition to the machinery of government of the United States.

This extradition had to be barred under Section 81 of the Extradition Act because its entire purpose was to silence those political opinions. Again, there were numerous cases on record of how courts should deal, under the European Convention, with states reacting to people who had revealed official criminality.

In the judgment being appealed Judge Baraitser did not address the protected nature of speech exposing state criminality at all. That was plainly an error in law.

Baraitser had also been in error of fact in stating that it was “Purely conjecture and speculation” that the revelation of US war crimes had led to this prosecution. This ignored almost all of the evidence before the court.

The court had been given evidence of United States interference with judicial procedure over US war crimes in Spain, Poland, Germany and Italy. The United States had insulated its own officials from ICC jurisdiction. It had actively threatened both the institutions and employees, of the ICC and of official bodies of other states. All of this had been explained in detail in expert evidence and had been unchallenged. All of it had been ignored by Baraitser.

Following the publication of the Manning material, there had been six years of non-prosecution of Assange. Why was there then a prosecution after six years? What had changed?

Following the declaration by the International Criminal Court that it would use Wikileaks material to investigate US government officials for war crimes, US officials described Assange as “a political actor”. This period saw the origin of the phrase “non-state hostile intelligence agency”. Assange had been accused of “working with Russia” and “trying to take down the USA”.

Baraitser had acknowledged in her judgment the hostility from the CIA but stated that “the CIA does not speak on behalf of the US administration”.

It was important to note that it was after the Baraitser judgment that Yahoo News had published its investigation into the US government plot against Assange.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Featured image is from Lawyers for Assange