Art and Struggle: Olive Trees as a Symbol of Palestinian Culture, Resistance and Peace

“the way that the trees can survive and have deep roots in their land so, too, do the Palestinian people.”

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the Translate Website button below the author’s name.

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Click the share button above to email/forward this article to your friends and colleagues. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

“I hugged the olive tree. It was precious to me, so I hugged it. I felt like I was hugging my child. I’d raised the tree like my child. They attacked around 500 trees filled with olives. Each tree could have filled two sacks of olives. They destroyed my olive tree, but I grew them back. I tended them and they came back even better than before. Settlers will never be able to take my land. This is our land not theirs. We will keep resisting until the world ends.” –Mahfodah Shtayyeh (2005 video)

“I hugged the olive tree… I’d raised the tree like my child.”

On November 27, 2005, a Palestinian woman was photographed hugging an olive tree after it was attacked by Israeli settlers.

Get to know the story behind this iconic image. pic.twitter.com/YUS57QjrFc

— Al Jazeera World (@AlJazeeraWorld) November 10, 2023

November 26 will be World Olive Tree Day according to the 40th session of the UNESCO General Conference (2019). The olive tree has symbolised peace and harmony for millennia.

World Olive Tree Day was proclaimed at the 40th session of the UNESCO General Conference in 2019 and takes place on 26 November every year. The olive tree, specifically the olive branch, holds an important place in the minds of men and women. Since ancient times, it has symbolized peace, wisdom and harmony and as such is important not just to the countries where these noble trees grow, but to people and communities around the world.

Think ‘holding out an olive branch’, an idiom that comes from Genesis 8:11 where we read “And the dove came into him in the evening; and, lo, in her mouth was an olive leaf plucked off: so Noah knew that the waters were abated from off the earth.”

However, in Palestine where the people have been cultivating olives for thousands of years, the olive tree has itself become a subject of destructive battles as settlers cut down or burn the olive groves. Al-Walaja, for example, is a Palestinian village in the occupied West Bank, four kilometres northwest of Bethlehem and is the site of Al-Badawi, an ancient olive tree “claimed to be approximately 5,000-year-old and therefore the second oldest olive tree in the world after “The Sisters” olive trees in Bchaaleh, Northern Lebanon.”

It is estimated that about 700,000 Israeli settlers are living illegally in the occupied West Bank and extremist elements are becoming more violent. In October this year (2023) a Palestinian farmer harvesting olives “was shot dead by settlers in the occupied West Bank city of Nablus. ‘We are now during the olive harvest season – people have not been able to reach 60 percent of olive trees in the Nablus area because of settler attacks,’ according to Ghassan Daghlas, a Palestinian Authority official monitoring settler activity.”

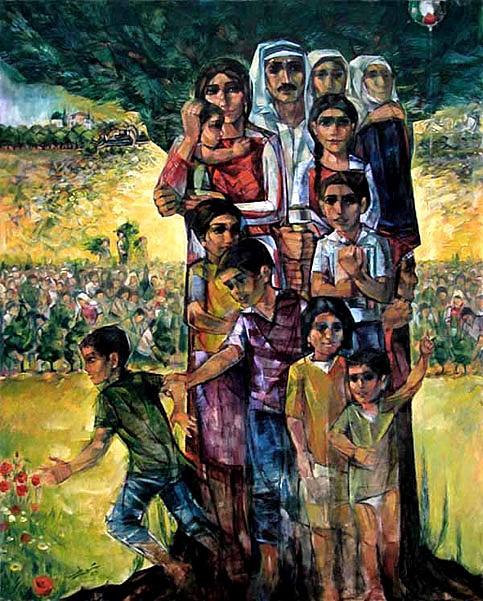

Olive Tree by the late Ismael Shammout

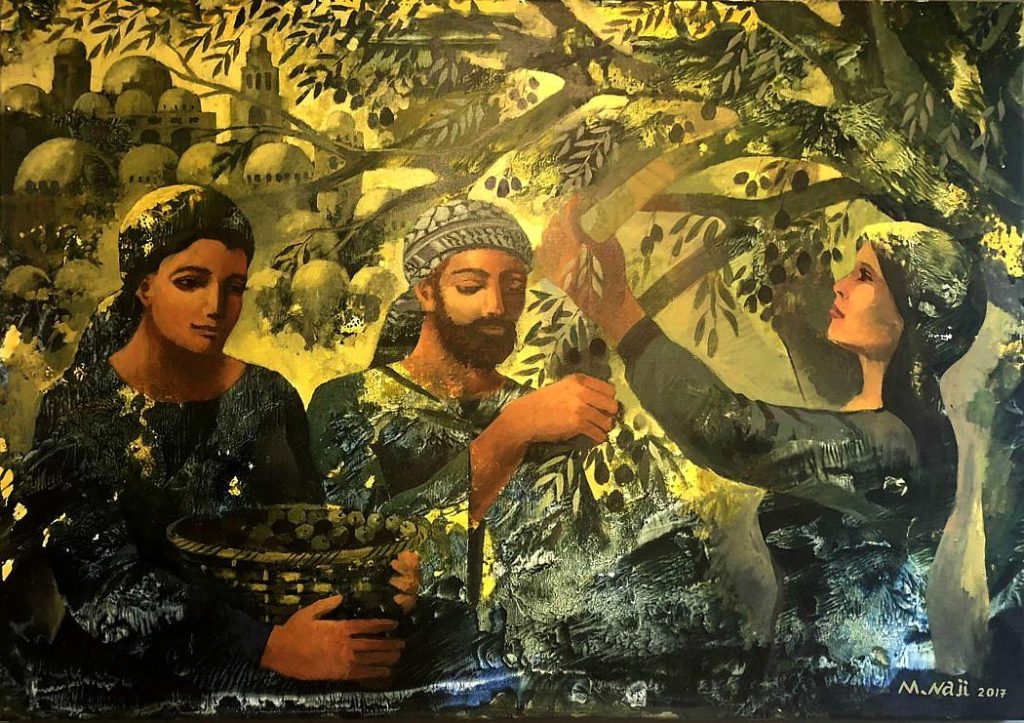

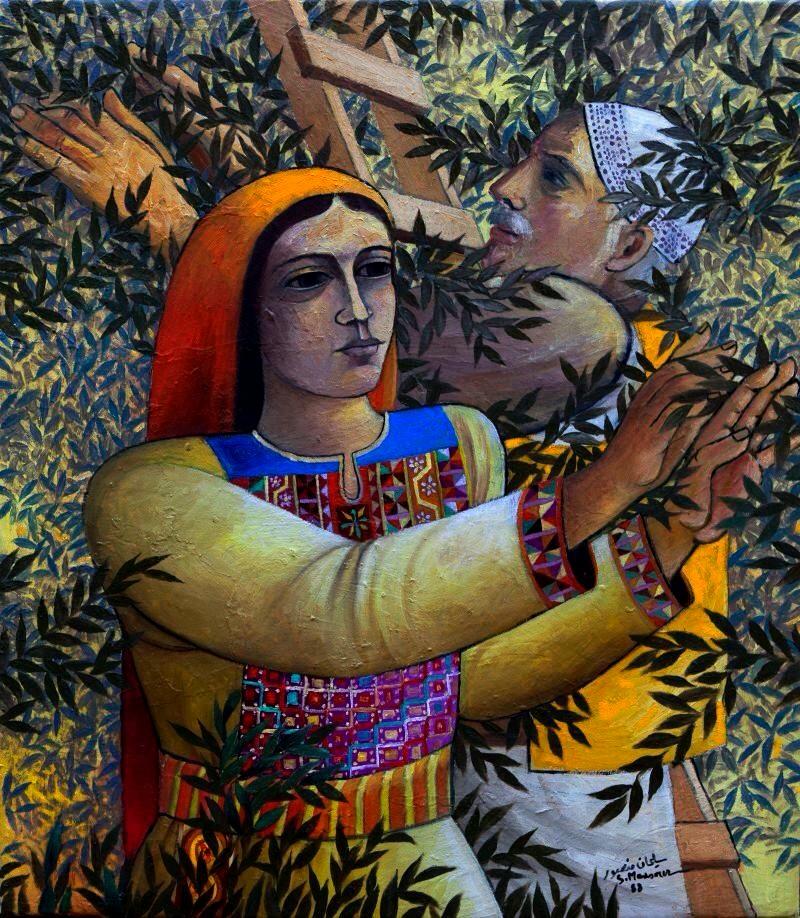

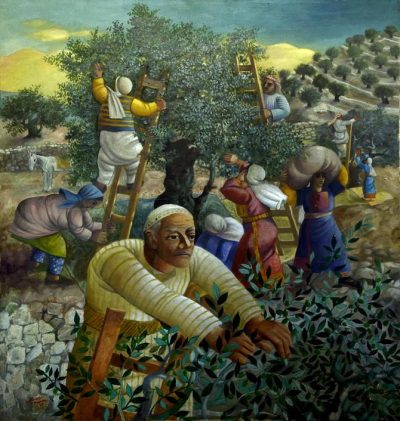

Traditionally, harvest time would bring families and neighbours together, helping each other in a process called “al Ouna”. The importance to these communities for unity and an income has led to the trees being depicted in the arts, and in particular the visual arts. Many paintings show farmers and families gathering the olives or show the ancient trees as symbols of their struggle and resilience.

“Olive Harvest” by Maher Naji.

The close connection between the farmers and their trees was famously illustrated in the photo of Mahfodah from the village of Salem hugging what is left of one of her olive trees. This photo has since been the source of many posters and paintings illustrating the political conflicts that the people have been forced to endure.

Salem (2005)

Life for the artists has not been easy either. They have focused on themes such as nationalism, identity, and land. As a result, their art can be political and the artists “sometimes suffer from the confiscation of artwork, refusal to license artists’ organizations, surveillance, and arrests.”

Olive picking (1988) by Sliman Mansour

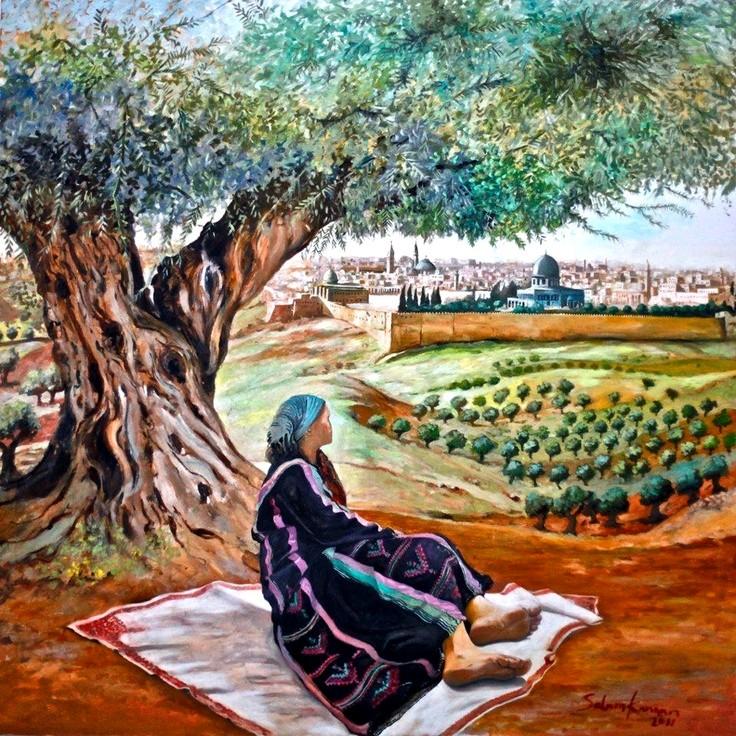

According to Sliman Mansour, a Palestinian painter based in Jerusalem, the olive tree “represents the steadfastness of the Palestinian people, who are able to live under difficult circumstances”, and like the “way that the trees can survive and have deep roots in their land so, too, do the Palestinian people.”

Painting by Salam Kanaan

Sometimes the paintings and posters incorporate other symbols of Palestinian identity like the City of Jerusalem (al-Quds), plants like Jaffa oranges, watermelon and corn, religious symbols, or the Palestinian flag.

Other traditional Palestinian arts like embroidery have used the olive tree in different ways. For example, the Palestinian History Tapestry “uses the embroidery skills of Palestinian women to illustrate aspects of the land and peoples of Palestine – from Neolithic times to the present. In the past, Palestinian embroiderers have mainly used cross stitch (tatreez) and geometric designs to decorate dresses and other items.”

Olive harvest [59 x 110 cm]. Design: Hamada Atallah [Al Quds] Al Quds, Palestine Embroidery: Dowlat Abu Shaweesh [Ne’ane], Ramallah, Palestine

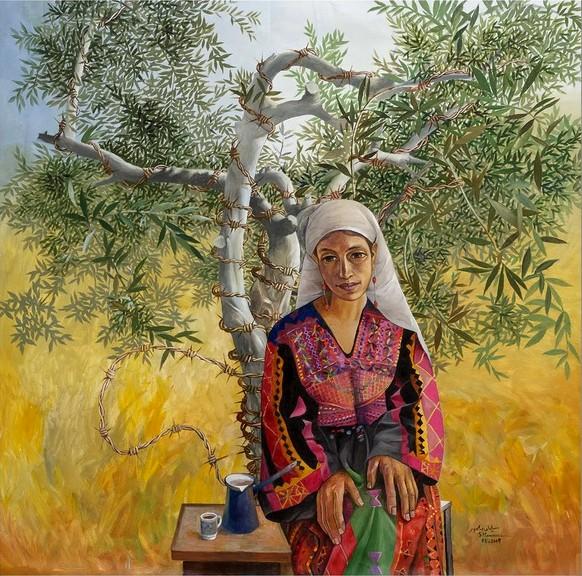

The symbolism in art can take on even harsher characteristics like Sliman Mansour’s painting of an olive tree wrapped in barbed wire (Quiet morning). The subject, a woman in a beautifully embroidered dress, is contrasted with the denial of access to the olive tree and therefore access to her birthright (the past) and an income (the future).

Quiet morning (2009) by Sliman Mansour

The olive trees have provided a steady source of income from their fruit and the “silky, golden oil derived from it”. Moreover, it is believed that “between 80,000 and 100,000 families in the Palestinian territories rely on olives and their oil as primary or secondary sources of income. The industry accounts for about 70 percent of local fruit production and contributes about 14 percent to the local economy.”

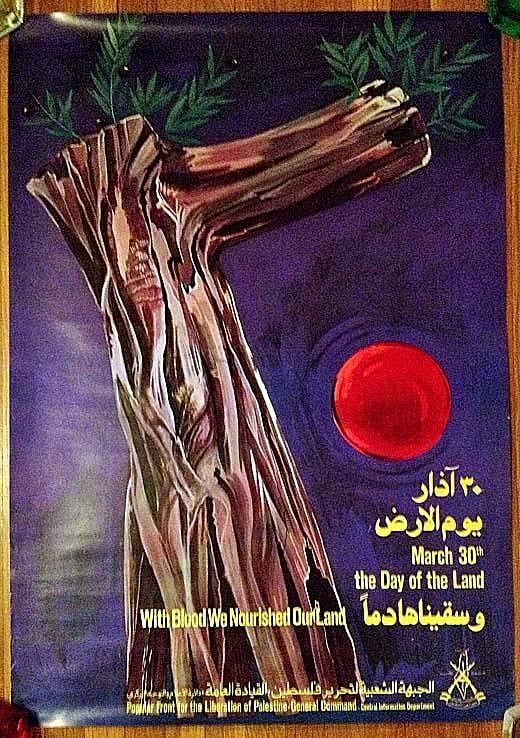

Poster by Abu Manu (1985)

However, the idea of recovery and renewal is also a common theme as the resilient olive tree with its deep roots is shown to be able to recover its vigour despite being chopped down. This has provided inspiration for the farmers and artists alike. The struggle for nature has always been intertwined with the struggle for life, and respect for the olive tree has always been reciprocated with abundance over the millennia.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share button above. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Caoimhghin Ó Croidheáin is an Irish artist, lecturer and writer. His artwork consists of paintings based on contemporary geopolitical themes as well as Irish history and cityscapes of Dublin. His blog of critical writing based on cinema, art and politics along with research on a database of Realist and Social Realist art from around the world can be viewed country by country here. Caoimhghin has just published his new book – Against Romanticism: From Enlightenment to Enfrightenment and the Culture of Slavery, which looks at philosophy, politics and the history of 10 different art forms arguing that Romanticism is dominating modern culture to the detriment of Enlightenment ideals. It is available on Amazon (amazon.co.uk) and the info page is here.

He is a Research Associate of the Centre for Research on Globalization (CRG).

Featured image: Painting by Sliman Mansour