Art and Culture: How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above

This article was originally published in April 2013.

Considering the possibility of a truly proletarian art, the great English literary critic William Empson once wrote, “the reason an English audience can enjoy Russian propagandist films is that the propaganda is too remote to be annoying.” Perhaps this is why American artists and bohemians have so often taken to the political iconography of far-flung regimes, in ways both romantic and ironic. One nation’s tedious socialist realism is another’s radical exotica.

But do U.S. cultural exports have the same effect? One need only look at the success of our most banal branding overseas to answer in the affirmative. Yet no one would think to add Abstract Expressionist painting to a list that includes fast food and Walt Disney products. Nevertheless, the work of such artists as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Willem de Kooning wound up as part of a secret CIA program during the height of the Cold War, aimed at promoting American ideals abroad.

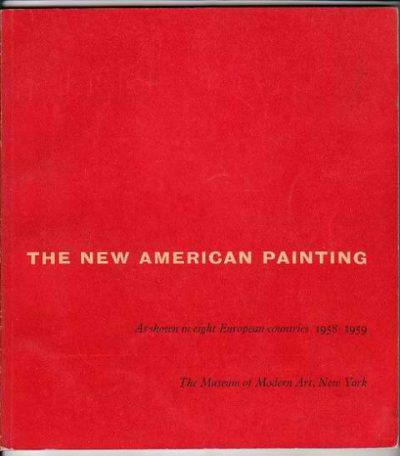

The artists themselves were completely unaware that their work was being used as propaganda. On what agents called a “long leash,” they participated in several exhibitions secretly organized by the CIA, such as “The New American Painting” (see catalog cover at top), which visited major European cities in 1958-59 and included such modern primitive works as surrealist William Baziotes’ 1947 Dwarf (below) and 1951’s Tournament by Adolph Gottlieb above.

Of course what seems most bizarre about this turn of events is that avant-garde art in America has never been much appreciated by the average citizen, to put it mildly. American Main Streets harbor undercurrents of distrust or outright hatred for out-there, art-world experimentation, a trend that filters upward and periodically erupts in controversies over Congressional funding for the arts. A 1995 Independent article on the CIA’s role in promoting Abstract Expressionism describes these attitudes during the Cold War period:

In the 1950s and 1960s… the great majority of Americans disliked or even despised modern art—President Truman summed up the popular view when he said: “If that’s art, then I’m a Hottentot.” As for the artists themselves, many were ex-communists barely acceptable in the America of the McCarthyite era, and certainly not the sort of people normally likely to receive US government backing.

Why, then, did they receive such backing? One short answer:

This philistinism, combined with Joseph McCarthy’s hysterical denunciations of all that was avant-garde or unorthodox, was deeply embarrassing. It discredited the idea that America was a sophisticated, culturally rich democracy.

The one-way relationship between modernist painters and the CIA—only recently confirmed by former case officer Donald Jameson—supposedly enabled the agency to make the work of Soviet Socialist Realists appear, in Jameson’s words, “even more stylized and more rigid and confined than it was.” (See Evdokiya Usikova’s 1959 Lenin with Villagers below, for example). For a longer explanation, read the full article at The Independent. It’s the kind of story Don DeLillo would cook up.

William Empson goes on to say that “a Tory audience subjected to Tory propaganda of the same intensity” as Russian imports, “would be extremely bored.” If he is correct, it’s likely that the average true believer socialist in Europe was already bored silly by Soviet-approved art. What surprises in these revelations is that the avant-garde works that so radically altered the American art world and enraged the average congressman and taxpayer were co-opted and collected by suave U.S. intelligence officers like so many Shepard Fairey posters.

*

All images in this article are from the author.