“To Hate All Things Russian”: Russia’s Contributions to the Treasure-trove of World Civilization

All Global Research articles can be read in 51 languages by activating the “Translate Website” drop down menu on the top banner of our home page (Desktop version).

To receive Global Research’s Daily Newsletter (selected articles), click here.

Visit and follow us on Instagram, Twitter and Facebook. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

***

In his article for The Atlantic of July 24, 2022 “Don’t Blame Dostoevsky,” Mikhail Shishkin makes a false start right away.[i] He rationalizes hate for a nation and its culture in the first sentence: “I understand why people hate all things Russian right now.” From the outset he tells readers it is permissible to hate an entire nation if one can manufacture an “acceptable” reason for this hatred. Thus “people” can go ahead and hate; Mr. Shishkin has just given the world a license. Such an attitude is clearly allowed in the West, for Russia and things Russian are not protected from hate speech.[ii] Regardless of how one views the current conflict between Russia and Ukraine, it does not justify dismissing things Russian or hating Russians; ideological convictions do not give individuals the right to denigrate a nation’s culture or demean its people.

Screenshot from The Atlantic

Russia’s contributions to the treasure-trove of world civilization are too numerous and superlative to mention here. It is not necessary to enumerate them. To eliminate Russian literature from university curricula, as was recently attempted in Milan, would negatively impact those students’ world cultural literacy. The European examples of Russia hatred and slavish following of anti-Russia sanctions abound.[iii] As recent diplomatic blunders have demonstrated, such as UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss’s ignorance of basic geography (surely a desideratum for her job?), international education and cultural literacy matter beyond the humanities. Among the characteristics of Russian literature that make it so powerful and affecting are its deeply humane and penetrating content, a fullness of respect for the absolute value of each human being, and acknowledgment of the mystery of human nature. Readers from all walks of life return to it again and again, enriching their interpersonal communications and ability to empathize with others.

Mr. Shishkin notes that “people” hate all things Russian. Which people? During the period leading up to Russia’s military operation in Ukraine, 2014-2022, when Ukrainians of the Donbas were being terrorized by their own government, Russia hatred was carefully curated by the United Kingdom, the EU, and the U.S. with its Five Eyes allies (adding Canada, Australia, and New Zealand to the mix). However, this does not represent the whole world. In fact, it captures only a small part of it. The Global South, most of Asia, and the Middle East enjoy at least cordial and even warm cultural and economic relations with Russia—for the Soviet Union / Russia was not an invader and colonizer of those lands.

Within the span of only a few pages, Mr. Shishkin simultaneously argues that Russian literature is (when it fights the state) and is not a weapon (has not enabled current atrocities)–but let us make allowances, for critics of Russia do suffer from circular logic and double standards. Otherwise, they would be penning essays that begin with, “I understand why people hate all things American (British, Saudi Arabian, German) right now.” But are those critics aware that, despite the fact that the U.S. imposed severe sanctions on Russia after the 2014 reunification of Crimea with the peninsula’s historic homeland, Russia did not express hatred for things American? During the 2018 FIFA World Cup held in various cities in Russia, in St. Petersburg on July 4 Russian professional musicians performed “The Star Spangled Banner” on Nevsky Prospect to honor the American national holiday. We were there.

Fair-minded and well-educated persons in the humanities and sciences all over the world do not hate Russian culture or Russians. Despite the fact that Germany was at war with Russia between 1914-1918, the composer-pianist Sergei Rachmaninoff refused to vilify the German nation.[iv] The Soviet Union was able to mend ties with Germany after World War II, despite the atrocities committed against Soviet citizens and the Red Army during the war.

The author seems to position himself as an expert, a Russian writer, one who continues “the humanist tradition of the intelligentsia” that has for ages battled “a Russian population stuck in a mentality from the Middle Ages,” “a pyramid of slaves” beaten into obedience. Who could possibly have empathy for such a people?! Only Russian writers who, according to Mr. Shishkin, have resisted unacceptable tsars for the sake of those silent barbarians. It is a fact that several generations of Western historians built their narratives based on the suppositions of their cultural peers and a dearth of availability of authentic materials in Soviet archives. Now that many Russian archives are open to researchers both Russian and international, the genuine historical record is available—which is producing major rehistoricizing and lively discussion of such maligned or caricatured figures as Tsar Nicholas II and his family, the mystic Grigory Rasputin, and Pyotr Nikolaevich Wrangel, to name only a few.

In addition to conflating all of Russian literature into only the dissenting pieces, Mr. Shishkin reduces Russian history to an endless, joyless gulag devoid of any achievements or enjoyment. Even a cursory review of Russian history problematizes such a sweeping statement. Between the eighteenth century of Catherine II’s reign (1762-1796) and the early twentieth century when Russia, as other European countries, was evolving into a constitutional monarchy, the Russian social and cultural landscapes were a complex tapestry of existence in which people’s lives were ordered by well-established patterns. The lives of peasants, intellectuals, and nobility were far from perfect, but there were many achievements and satisfactions therein. Deep-rooted past traditions have been restored to Russia, such as the democratic Cossack stanitsas (villages) in the Caucasus, and the Feast Days of the Russian Orthodox Church (a foundational feature of Russian culture), at the same time as new highways and airports continue to appear to link major cities. It is not by accident that the elegant and moving stories and novels of the Village Prose writers such as Valentin Rasputin, Vladimir Soloukhin, Vasily Belov, and others sought to correct—because of their own experiences and memories of growing up as peasants—erroneous and negatively biased assumptions about the Russian common people. They were there.

Mr. Shishkin’s article does not manifest empathy for average Russians. Contempt for Russians is evident in the epithets he chooses for them (“a pyramid of slaves worshiping the supreme khan,” Russia is “a slave empire,” “slaves give birth to a dictatorship,” “Russian population stuck in a mentality of the Middle Ages,” “fascists, murderers”), and his pointed phrases deprive the Russian people of agency (they are “forced to sing patriotic songs,” “forced to endure and suffer,” “the state has been hammering the Russkiy mir [Russian World] view into people’s brains”). Russians–the barbarians that they are, stuck in the Middle Ages–need liberation and guidance, in Mr. Shishkin’s opinion. But it is a historical fact that the “Russkiy mir view,” as the author puts it, originated in the essential features of Russian culture itself. These cannot be “hammered in,” for they were organically formed across the centuries by the people themselves. As all sovereign countries, Russia should be measured by its own yardstick, not by norms and values artificially imposed on it by the West.

According to Mr. Shishkin, Russians (damn slaves!) put trust in their tsars, but their true salvation comes from so-considered enlightened writers.[v] He divorces Russian culture from the nation; thus everyday people exist outside of “culture”; the nebulous intelligentsia represents the only beacon and carrier of any culture worth knowing. “The civilizational gap that still exists in Russia between the humanist tradition of the intelligentsia and a Russian population stuck in a mentality from the Middle Ages can be bridged only by culture—and the regime today will do everything it can to prevent that” [emphasis original]. Such a sensational generalization implying that the Russian government prevents the development and flourishing of literature, music, and the visual arts (both in traditional high culture and the folk arts) is just not true. Anyone who has spent time in Russia can easily refute this claim. It is the people themselves and Russia’s high-quality educational system in general and in the arts in particular—for many, the envy of the world—that are creating the works that will join the pantheon of Russia’s literary and cultural monuments.[vi] Perhaps there exists an “imaginary Russia” that the author envisions, because it is not the Russia we know.

The author reduces Russian people–the very inspiration, part and parcel of Russian literature and culture–to an obedient clueless horde, a quiet servile crowd that rejects freedom for safety and bread. They are weak, they are slaves. Who will save them? According to Mr. Shishkin, the few elect, enlightened, and cultured, the ones who know the “truth,” the poets (the humanists!)–the new Grand Inquisitors, indulging the weakness of poor uncritical blockheads and promising them light and freedom if they rise against the authority of the rulers the enlightened writers living abroad deem intolerable.

Curiously, Mr. Shishkin references Herzen and Chernyshevsky, not mentioning that their famous novels inspired the Russian revolutionaries who brought about bloodshed worse than many military conflicts and which in turn led to Stalin’s purges and terror that Mr. Shishkin decries. Since the probability that readers of The Atlantic have read What is to Be Done? and Who is to Blame? is pretty slim, an omission of key details of those novels would not be noticed.

This is not the only key fact the author omits. He fails to point out that Boris Yeltsin, the darling of the West of the 1990s, is as despised as the leaders whom he does mention. He does not speak of the complexity of the relationship between Russian poets/writers and the State, which was never simplistically black and white, nor does he disclose that none of the poets/writers he mentions ever felt contempt for the Russian people so categorically.

Does Mr. Shishkin have an awareness that he is rationalizing hatred and justifying Russophobia? Given the disdain, disrespect, and patronizing of Russians that permeate his essay, perhaps the real objective of the writing is not a defense of Russian literature and culture, but rather a feeble attempt not to be “canceled” along with them? If so, there are better ways to affirm one’s participation in and defense of a well-established literary tradition.

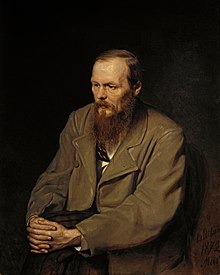

We recommend that all journalists and writers wishing to attain a profound understanding of Russian literature re-read Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov (1881), in particular the section titled “Exhortations of Elder Zosima.” The Elder in the tradition of Orthodox wisdom advises each person to [in a paraphrase] “walk round yourself every day and look at yourself; see how you appear to others”—and by extension, consider how you look to God. Regardless of whether or not one follows a faith tradition, surely a universal truth involves not hating the Other. The Russian woman gave bread to the German prisoner-of-war.

*

Note to readers: Please click the share buttons above or below. Follow us on Instagram and Twitter and subscribe to our Telegram Channel. Feel free to repost and share widely Global Research articles.

Alexandra G. Kostina, Ph.D., is a Russian linguistics and literature professor and cultural analyst. Born in Novgorod, Russia and currently residing in the U.S., Prof. Kostina travels widely internationally for her research in linguistics, media bias, and Russian literature. She has taught courses on Dostoevsky and includes his thought as well as that of contemporary Russian writers in her research.

Valeria Z. Nollan, Ph.D., is a Russian language and literature professor, poet, and musician. Born in Hamburg, Germany of Russian parents displaced by World War II, Prof. Nollan has made twenty-six extended research trips to Russia and Europe between 1985-2022. She has published or edited eight books and many articles on Russian literature and culture; has given poetry readings in Russia, Europe, and the U.S.; and has performed Russian music at various venues. Her poetry collection Holocaust of the Noble Beasts (Seattle, WA: Goldfish Press, 2020) engages issues of worldwide animal welfare, art, and music.

Notes

[ii] See, for example, Creating Russophobia: From the Great Religious Schism to Anti-Putin Hysteria, by Swiss journalist and politician Guy Mettan (Atlanta, GA: Clarity Press, 2017); and The American Mission and the “Evil” Empire: The Crusade for a “Free Russia” since 1881, by David S. Fogelsong (New York: Cambridge UP, 2007).

[iii] “German minister speaks out against boycott of Russian culture,” RT, July 3, 2022, https://www.rt.com/russia/558277-german-minister-boycott-culture/.

[iv] See my forthcoming biography Sergei Rachmaninoff: Cross Rhythms of the Soul (Lexington Books / Rowman and Littlefield, November 2022)—VZN.

[v] See The Rebirth of Russian Democracy, by Nicolai N. Petro (Cambridge, MA: Harvard UP, 1995), which traces the longstanding undercurrents of democracy within Russia’s political systems.

[vi] See https://www.currentschoolnews.com/education-news/best-educational-system-in-the-world/.

Featured image: Dostoevsky in 1872, portrait by Vasily Perov (Licensed under the public domain)