Analysis by Analogy: Myanmar Is Not Syria

Many geopolitical analysts and commentators have noted many worthwhile similarities between the Syrian crisis and the one now unfolding in the Southeast Asian state of Myanmar. However, what is different about these two crises is just as important as what is the same.

The Similarities

Particular focus has been placed on evidence emerging that US-ally Saudi Arabia is serving as an intermediary fueling militancy in Myanmar’s western Rakhine state. The militants, however, consist of a foreign armed, funded, and led cadre, constituting a numerically negligible minority of the Rohingya population they claim to represent, and are in fact no more representative of the Rohingya people than militants of Al Qaeda and the so-called “Islamic State” are representative of Syria or Iraq’s Sunni Muslim populations.

While it is crucial to point out the foreign-funded nature of a militancy attempting to co-opt the Rohingya minority in Myanmar, it is equally important to understand precisely where this militancy fits into Saudi Arabia’s and ultimately its American sponsors’ larger plans.

Another similarity pointed out by analysts is the use of US and European-funded fronts posing as nongovernmental organizations (NGOs). These include larger organizations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, as well as organizations on the ground in Myanmar funded by the US National Endowment for Democracy (NED), its various subsidiaries including the International Republican Institute (IRI), the National Democratic Institute (NDI), Freedom House, USAID, and Open Society.

These organizations are intentionally seeking to control the narrative, inflame rather than smooth over tensions, and create a pretext for wider and more direct intervention in Myanmar’s expanding crisis by Western nations.

Analysts and commentators, however, cannot stop here. They must commit to equal due diligence in unraveling what stands behind Myanmar’s government – who it was that assisted them into power during the relatively recent 2016 elections, who built up their political networks across the country over the course of several decades, and what role their actions play in Western designs for the nation’s near and intermediate future.

The Differences

Syria’s government is the creation and perpetuation of localized special interests – backed by various alliances ranging from the former Soviet Union in the past, to Russia, Iran, and to a lesser degree China in present day.

The United States and its Arab partners – particularly Saudi Arabia – have engineered militancy along and within Syria’s borders beginning in 2011 for the explicit purpose of overthrowing Syria’s government and dividing what remains of the nation among proxies and client regimes controlled from Washington, London, and Brussels.

In Myanmar, while the US and its Saudi partners are apparently fueling militancy among the Rohingya population, it was the US itself who for decades built up the political networks of the current ruling regime, with Aung San Suu Kyi a whole-cloth creation of Western media narratives, immense funding and political support, and a carefully crafted facade to obfuscate from the public for decades the true, nationalist and even genocidal nature of Suu Kyi’s supposedly “Buddhist nationalist” support base.

An extensive 2006 report by Burma Campaign UK titled, “Failing the People of Burma?” (PDF), would reveal how virtually every facet of Myanmar’s current government is a creation of Western political and financial support. (Note: The US and UK still often refer to Myanmar by its British colonial name, “Burma”).

Extensive efforts have been made to portray Myanmar’s head of state, Aung San Suu Kyi, as being opposed by ultra-violent nationalist “monks,” and many in the alternative media have wrongly concludes that the US seeks to pressure, even topple Suu Kyi from power. In reality, both Suu Kyi and her violent supporters are creations and a perpetuation of US cash and political support.

The report would lay this out in great detail, stating:

The restoration of democracy in Burma is a priority U.S. policy objective in Southeast Asia. To achieve this objective, the United States has consistently supported democracy activists and their efforts both inside and outside Burma…Addressing these needs requires flexibility and creativity. Despite the challenges that have arisen, United States Embassies Rangoon and Bangkok as well as Consulate General Chiang Mai are fully engaged in pro-democracy efforts. The United States also supports organizations, such as the National Endowment for Democracy, the Open Society Institute (nb no support given since 2004) and Internews, working inside and outside the region on a broad range of democracy promotion activities. U.S.-based broadcasters supply news and information to the Burmese people, who lack a free press. U.S. programs also fund scholarships for Burmese who represent the future of Burma. The United States is committed to working for a democratic Burma and will continue to employ a variety of tools to assist democracy activists.

The 36-page report would enumerate US and European programs in detail – ranging from the creation and funding of media, to organizing political parties and devising campaign strategies for elections, to even scholarships abroad to indoctrinate an entire class of political proxies to be used well into the future upon transforming the nation into a client state. Virtually every aspect of life in Myanmar was targeted and overturned by Western-backed networks over the course of several decades and an untold amount of foreign-funding.

Similar evidence reveals that many of the so-called “Buddhist” nationalist groups also enjoy a close relationship with US and European interests and that they played a pivotal role in bringing Suu Kyi to power.

Additionally, many in Suu Kyi’s current government are the recipients of US-funded training. Narratives concerning the current Rohingya crisis are being crafted by Suu Kyi’s “Minister of Information,” Pe Myint.

Pe Myint was revealed in a 2016 article in the Myanmar Times titled, “Who’s who: Myanmar’s new cabinet,” to have participated in training funded by the US State Department. The article would report (emphasis added):

Formerly a doctor with a degree from the Institute of Medicine, U Pe Myint changed careers after 11 years and received training as a journalist at the Indochina Media Memorial Foundation in Bangkok. He then embarked on a career as a writer, penning dozens of novels. He participated in the International Writing Program at the University of Iowa in 1998, and was also editor-in-chief of The People’s Age Journal. He was born in Rakhine State in 1949.

The Indochina Media Memorial Foundation is revealed in a US diplomatic cable published by Wikileaks as fully funded by the US State Department through various and familiar intermediaries. The cable titled, “An Overview of Northern Thailand-Based Burmese Media Orgranizations.” would explicitly state (emphasis added):

Other organizations, some with a scope beyond Burma, also add to the educational opportunities for Burmese journalists. The Chiang Mai-based Indochina Media Memorial Foundation, for instance, last year completed training courses for Southeast Asian reporters that included Burmese participants. Major funders for journalism training programs in the region include the NED, Open Society Institute (OSI), and several European governments and charities.

Many of those among Myanmar-based US-funded “NGOs” apparently opposing Suu Kyi’s government are in fact alumni of the same US-funded programs as many members of the current government.

In essence, the primary difference between Myanmar and Syria is that while in Syria the US is fueling militancy to topple a government beyond its reach and influence, in Myanmar, the US is manipulating the entire nation via two vectors its controls entirely – a militancy it is growing on one side, and a political establishment it has created from whole-cloth on the other.

Moving Beyond Analysis by Analogy

Helping readers understand various aspects of the current crisis in Myanmar by comparing it to various aspects of Syria’s ongoing conflict can be instructive. However, drawing entire conclusions about the implications of the Myanmar conflict by simply assuming it is repeat of Western efforts in Syria is fundamentally flawed.

While the US seeks to divide and destroy the entire state of Syria, its efforts in Myanmar are concentrated to the western state of Rakhine with little possibility of spreading because of Myanmar’s demographics.

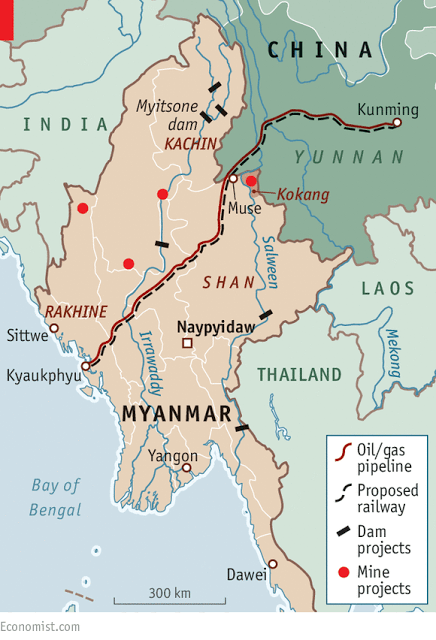

This is also precisely where China has invested deeply in its One Belt, One Road (OBOR) project, with a seaport in Sittwe, central Rakhine, and road, rail, and pipeline projects slated to expand onward toward China’s border and eventually Kunming.

Opposition in the form of local NGOs underwritten by US State Department cash, or violence covertly backed by the US and its intermediaries, have attempted to systematically disrupt Chinese infrastructure projects around the globe, including in Myanmar. Chinese-built dams in Myanmar are opposed by networks of US-funded NGOs, militant groups accused of receiving US backing have attacked Chinese projects throughout the nation, and the current conflict in Rakhine fueled on both sides by the US threaten to not only derail Chinese projects there, but may even serve as a pretext for positioning Western forces inside Myanmar – a nation that directly borders China.

Placing American forces – in any capacity – along China’s borders has been a long-term stated goal of US policymakers for decades. From the Vietnam War-era Pentagon Papers to the 2000 Project for a New American Century report, “Rebuilding America’s Defenses,” to former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton‘s “Pivot to Asia” policy, a singular theme of encircling and containing China either with client states obedient to Washington, or chaos all along China’s peripheries has prevailed.

Analysts and commentators must account for the decades of US and European funding that placed the current government of Myanmar into power. They must account for the surgical nature of destabilization confined to Myanmar’s Rakhine state versus the full-spectrum destabilization being fueled in Syria. They must also identify the motives underpinning US designs in Myanmar.

Simply assuming that a US-Saudi-backed militancy exists to topple a government rather than grease the wheels for another, more indirect objective – one that perhaps even aims at preserving Myanmar’s current government rather than toppling it by pinning blame on the nation’s still powerful and independent military – will only aid rather than impede injustice. Analogies drawn from two different conflicts are only helpful in simplifying explanations and conclusions analysis by deep research have already arrived at.

Tony Cartalucci is a Bangkok-based geopolitical researcher and writer, especially for the online magazine“New Eastern Outlook”.

This article was originally published by New Eastern Outlook.

All images in this article are from the author.