Amy Ashwood Garvey: A Forerunner in Pan-Africanist Feminism of the 20th Century

Co-founder of the UNIA-ACL, the first wife of Marcus Garvey worked tirelessly for women’s rights and inter-continental unity from the Caribbean and Central America to the United States, Europe and Africa

Alongside and in opposition to the rise of colonialism across the African continent, a movement of resistance to European domination surfaced during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

However, the advent of colonialism in South America, Central America, the Caribbean and North America was well underway by the early decades of the 16th century. The colonial occupation of the western hemisphere was closely linked to the forced removal and extermination of the indigenous peoples and the importation and exploitation of African labor.

During the course of the Atlantic Slave Trade, Africans rose up in rebellion against European domination. These rebellions were often sporadic however many were well-organized and resulted in the establishment of African communities.

In Brazil, the Caribbean and in the U.S., these self-governing communities known as Quilombos, Maroons, Black Seminoles, etc. served as a testament in the affirmation of the human quest for self-determination, national independence and Pan-Africanism. By 1804, the African people of Haiti had led a successful revolution founding a republic right out of the system of enslavement, the first of such accomplishments in world history.

Africans from the U.S. and the Caribbean were instrumental in the development of nationalist and Pan-Africanist movement which would influence world history. From the initial Pan-African Congress in Chicago in 1893 to the First Pan-African Conference of 1900 in London, people from the Caribbean and the U.S. played a leading role.

Historical figures such as Henry Sylvester Williams of Trinidad along with W.E.B. Du Bois and Anna J. Cooper of the U.S., articulated positions that emphasized the necessity of independent thought and political action. By 1914, a new organization would surface in Jamaica known as the Universal Negro Improvement Association and the African Communities Imperial League (UNIA-ACL). The group was founded by Marcus Garvey and Amy Ashwood during the same year as the beginning of the First World War (1914-1918)

Amy Ashwood was born on January 18, 1897 in San Antonio, Jamaica, one of three children born to Delbert Ashwood and Maudriana Thompson. The Ashwood daughter spent considerable time in her earlier years in Panama where her father operated a restaurant and printing business. She was later sent back to Jamaica to attend high school where she met Marcus Garvey at a public debate.

Garvey was ten years her senior being born on August 17, 1887. He had studied printing in Jamaica and under the Egyptian-Sudanese anti-colonial Pan-Africanist Duse Mohamed Ali in London during 1912-13. Garvey had also traveled in Central America where he witnessed the deplorable conditions of Africans working in the construction projects surrounding the Panama Canal as well as the cultivation of cash crops for the U.S. corporate agricultural firms.

Amy Ashwood and the Role of Women in the UNIA-ACL

Although Garveyite historian Tony Martin doubted the claim by Amy Ashwood that she had co-founded the UNIA-ACL, documents indicate that she had served as an organizational secretary and initiator of the Women’s division. All chapters of the organization were required to have both a male and female president. Between 1916 and 1918, Ashwood had returned to Jamaica while Garvey relocated to the U.S. in Harlem.

They would reunite in 1918 and marry by late 1919 in an elaborate ceremony at Liberty Hall in Harlem. Nonetheless, the marriage only lasted for several months. Their break-up was abrupt and her departure from the UNIA-ACL was not on favorable terms. By 1922, Garvey had remarried to Amy Jacques, who became a well-known leader within the UNIA-ACL, authoring the book “The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey” while he fought federal prosecution and imprisonment on trump-up charges of mail fraud.

Despite Ashwood-Garvey’s rupture with the organization she continued to play a pioneering role in the emerging struggles for national liberation and Pan-Africanism. Her creative impulses led her into a career as a public speaker, theatrical producer, writer and restaurant owner.

According to Rhone Fraser, “Around 1923, Ashwood met legendary Calypsonian singer Sam Manning (from Trinidad) and begins a professional and romantic relationship with him as a pioneering musical theatre producer. She and Manning write and produce several plays described by both Lionel Yard (a biographer of Ashwood-Garvey) and Martin. Sandra Pouchet Paquet’s edited 2007 collection of essays on Calypso, called Music, Memory, Resistance: Calypso and the Caribbean Literary Imagination, shows calypso as a critique or mocking of the colonial order that Manning’s music provided in a subtle way.” (Advocate, Oct. 18, 2016)

Ashwood-Garvey and Manning produced three musicals–Hey, Hey!, Brown Sugar, and Black Magic. The productions ran at the Lafayette Theatre in New York along with other locations in the U.S. and the Caribbean.

In 1924 she visited England and assisted in the founding of the Nigerian Progress Union (NPU) with Ladipo Solanke. The NPU was closely associated with the West African Student Union (WASU), an early regional Pan-Africanist formation in London.

Pan-Africanism and Anti-Imperialism

After a series of artistic endeavors by 1936, Ashwood-Garvey returned to England where she opened the Florence Mills Social Parlor, a nightclub and gathering venue in London’s West End. The club was a meeting place for African and African-Caribbean liberation movement organizers and intellectuals. Some of the well-known personalities who frequented the club included the Guyanese Pan-Africanist Ras T. Makonnen, George Padmore and C. L. R. James, leading Pan-Africanist and socialist activists, who were also from Trinidad.

Ashwood-Garvey was a friend and collaborator with other notables such as Kenyan leader Jomo Kenyatta, and the Ghanaian scholar J. B. Danquah. After the Italian fascist invasion of Ethiopia in 1935, Ashwood-Garvey assisted in the initiation of the International African Friends of Abyssinia (IAFA), which was later renamed the International African Service Bureau (IASB). She served as treasurer of the IAFA and IASB vice president. The organizations vigorously opposed the Italian invasion and occupation of Ethiopia. They appealed to other imperialist states to impose economic sanctions against Italy while setting up an Ethiopian self-defense fund. Ashwood-Garvey rekindled her links with Solanke and the WASU along with sharing speaker platforms with Padmore across England.

During World War II Ashwood-Garvey’s organizational work expanded to encompass efforts to promote educational opportunities for women. In addition she advocated for decent wages for African-Caribbean working women. She returned to Jamaica during the War where she administered a school of domestic science.

Towards the end of WWII in 1944, she returned to New York and became involved in campaigning for Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. when he was elected to Congress as the first African American Congressman from New York City. When the WWII concluded the following year, the struggle for national independence and Pan-Africanism accelerated.

The National Biography Online states that: “She participated in the 1944 ‘Africa-New Perspectives’ conference of the Council on African Affairs (CAA) with the actor and civil rights activist Paul Robeson and the future Ghanaian leader Kwame Nkrumah, and in April 1945 attended the Colonial Conference convened by the historian W. E. B. Du Bois. She spoke for women’s rights in meetings of the West Indies National Council and at CAA rallies, and she founded the nonprofit Afro-Women’s International Alliance to provide day care, adult education, and aid to mothers living in poverty. She helped organize the Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester, England, which she addressed in October 1945 on the issue of black workingwomen and fair wages.” (http://www.anb.org/articles/15/15-01356.html)

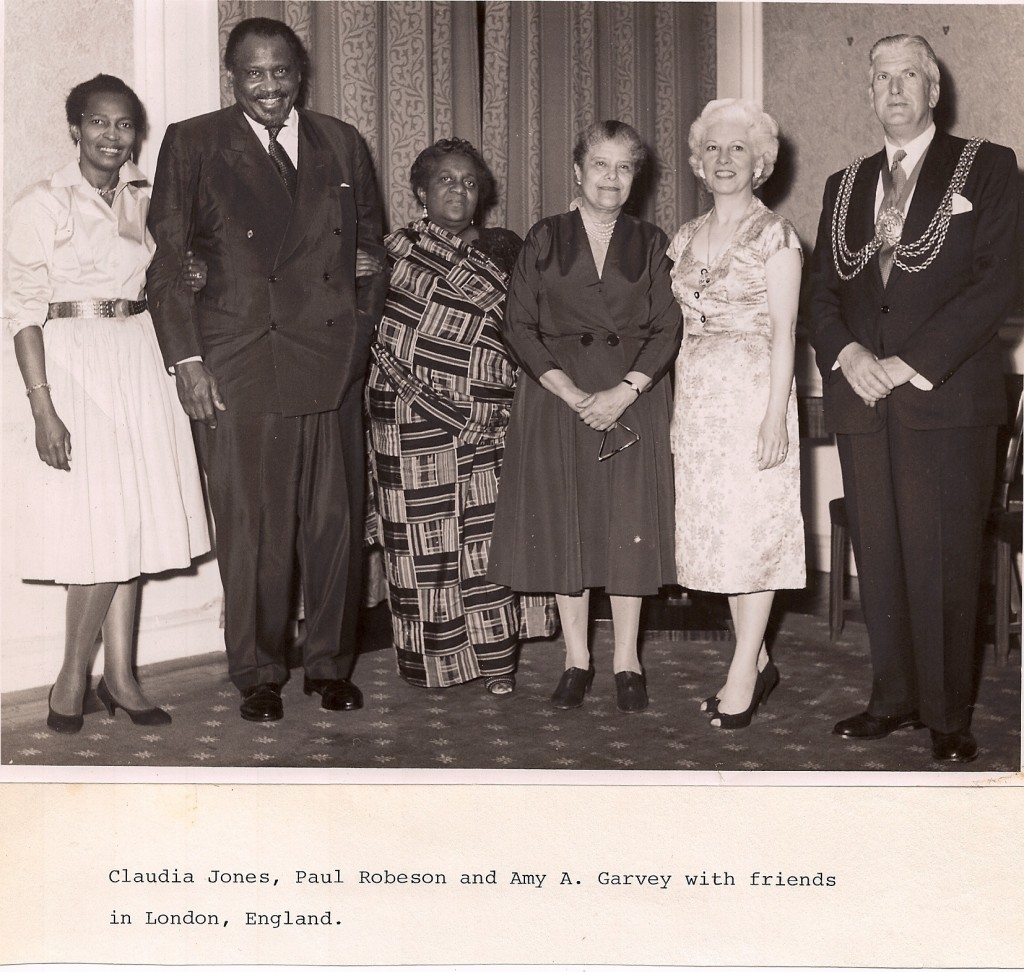

Ashwood-Garvey traveled widely and lived for extended periods in the West African states of Liberia and the-then Gold Coast. She maintained her connections with developments in Britain working with African-Caribbean Communist journalist and organizer Claudia Jones who had been imprisoned and deported from the U.S. during the McCarthy era of the mid-1950s. Jones became a leading figure in the African community in Britain founding the West Indian Gazette newspaper and the annual Carnival which focused on Caribbean cultural expressions.

By the 1960s, the African American movement for Civil Rights and Black Power had gained international attention. There was increased interest in issues involving nationalism, feminism and Pan-Africanism. Ashwood-Garvey toured as a lecturer in the U.S. from 1967-1969, after which she returned to Britain. She passed away from natural causes on May 3, 1969 in Jamaica.

The contributions of Amy Ashwood-Garvey are quite instructive for developments in the 21st century with the rethinking of African, African Caribbean and African American political historical processes. Her indefatigable efforts provide inspiration to successive generations of activists throughout the African world.