National Sovereignty, Canada Day 2019: America’s Plan to Wage War on Canada in the 1930s

U.S. tactics included troop invasions, use of poison gas and aerial bombings of major Canadian cities

The current U.S. president’s bullying of Canada over trade issues is causing some Canadians to question just how close our relationship is with our neighbour to the south. Peter Bailey tells the tale of a time not so long ago when hawkish voices in the U.S. were plotting the ultimate hostile act – a full-scale invasion of Canada.

This is probably the damnedest story you’ll read all week. If you think our trade wars with the U.S. are bad, keep in mind that at one time things could have got a lot worse.

As the Great Depression started in late 1929, the American military drew up a top-secret project titled “War Plan Red,” a scheme to wage war with Great Britain. Under Joint Army and Navy Board codes, America was known as “Blue,” Britain was “Red” and Canada was called “Crimson.”

Oddly enough, the Americans also made plans for war against Japan, designated “War Plan Orange,” and Germany, “War Plan Black.” But once rumours got out about another possible war against a German regime, isolationists in the U.S. made clear their opposition to conflict in Europe and the military lost its enthusiasm. Indeed, later on, the “Plan Dog” memo came out with its analysis of a two-front war with Britain and Japan (War Plan Red-Orange), which the U.S. realized it couldn’t sustain. So by 1930 it decided to concentrate on one front, Britain.

Except almost all of America’s destructive power would be directed against Canada.

What led up to it?

When the U.S. entered the First World War in 1917, it fought as an associated power, not a British ally. At war’s end, the other allies reneged on paying their debts to Britain. The British owed America £9 billion. The U.S. demanded repayment, which tarnished the image of the U.S. in Britain. The American image of the British, in turn, was of an ungrateful nation that wanted their war debts cancelled.

Image on the right: Lockheed Martin B-10 bomber: Secret plans to build three air bases along the Canadian border were leaked.

Tensions between the two nations remained on edge for more than a decade. By 1927, talks at the Geneva Naval Conference went badly, actually increasing the possibility of war between the two great powers. America was determined to throw its weight around; it just wasn’t sure how.

According to Dr. Christopher Bell of Dalhousie University in Halifax, N.S., Winston Churchill considered that war was certainly a possibility “if we get ourselves into a position where the Americans can feel that they can push us around whenever they want to.”

Although on the American East Coast sentiments were with the British, in the Midwest and the West Coast, the feeling was decidedly anti-British. Some American strategists saw an opportunity to strike a decisive blow against war-weary Britain and to wrest control of some of her vast empire – including Canada – before she could revive her military strength. America’s flyboy hero Charles Lindbergh went so far as sympathizing with the growing Nazi movement and joined the America First movement.

Adolf Hitler, for his part, also thought a war between America and Britain was inevitable and he wanted the British to win. Bizarrely, he thought he could work with the British against the U.S.

The outline for War Plan Red shows the U.S. considered chemical warfare against Canadian and British troops. A memo signed by Gen. Douglas MacArthur approved the possibility, provided there was no treaty to prevent it. By 1935, authorization was granted for the use of poison gas.

The onset of the Depression only added to the feeling that war with Britain was almost inevitable. The depressed markets, mass unemployment, the Dust Bowl and political unrest made the possibility of a war a useful way to unite the people and get the economy working again.

How would the war be fought?

Image below: A quick invasion was planned to avoid giving Canada and Britain a chance to amass troops

The U.S. planned to start the conflict by moving 25,000 troops from Boston to hit Halifax, with a fleet bombardment of the harbour and an invasion. The plan was to prevent the British navy from shipping reinforcements to Canada.

Next, troops would cross from Fort Drum, N.Y., to strike Ottawa. A second army would cross from Buffalo into Niagara to shut down Ontario’s hydroelectric plants, to occupy Hamilton’s steel industries, and to head to Toronto by road.

We can assume the cities would have previously been attacked by the air force’s Martin B-10 bombers and perhaps bombarded by the U.S. Navy operating on Lake Ontario.

More troops would cross from Detroit and a third group would head north to Winnipeg. A fourth group would attack Vancouver.

The Americans assumed there would be a total of three million British and Canadian troops within a year, so they planned a quick invasion.

But Canada had a plan – Defence Scheme No. 1.

The scheme was created in 1921, probably due to murmurings and fears of a U.S. invasion of Canada. It was created by the director of Military Operations and Intelligence, Lt.-Col. James “Buster” Sutherland Brown. It called for a surprise invasion of the northern U.S. states to buy time so Britain could send reinforcing troops by sea.

Canadian raids would attempt to seize Seattle, Spokane and Portland in the west. In the prairies, troops would attack Fargo, N.D., and move on to Minneapolis, Minn. Soldiers from Quebec would seize Albany, N.Y., and Maritime soldiers would invade Maine. Once American forces grouped, the Canadians would return home, burning bridges along the way to slow the U.S. advance.

Sutherland Brown felt confident because he had scouted New England with a few military pals, spying on the Americans’ weaknesses. He reported that in Vermont the people were “affable” but could become serious soldiers “if aroused.”

However, his plans, which were not co-ordinated with the British, were scrapped in 1928, two years before War Plan Red was introduced. It is just as well, because we now know Canada’s raiders would have been doomed.

What prevented the invasion?

By 1935, the U.S. organized giant troop movements and war games at Fort Drum, N.Y., just east of Kingston, Ont. It was the largest American military movement of its kind, with more than 25,000 troops mobilized and 15,000 held in reserve in Pennsylvania. But top-secret plans became public knowledge when the government printing office mistakenly made the documents public.

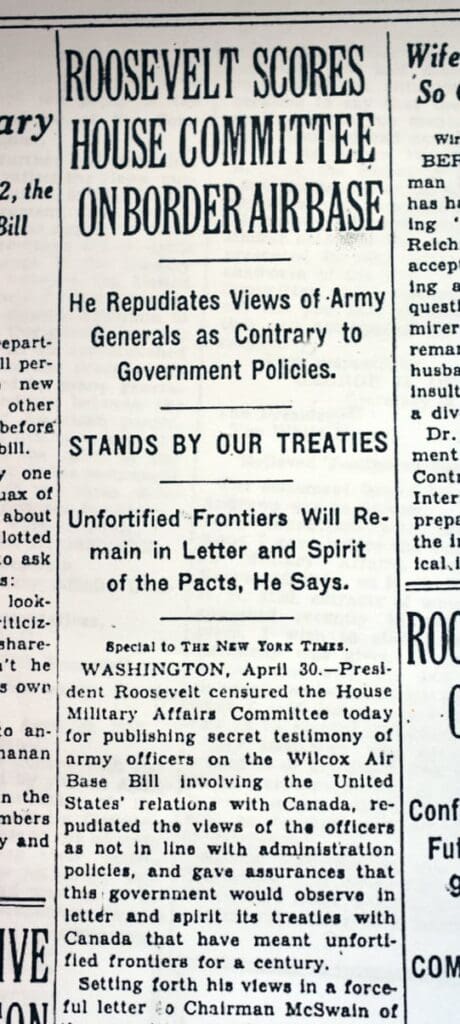

Secret plans to build three air bases along the Canadian border were now leaked. Newsreel companies came to film the construction process. On both sides of the border, newspapers argued back and forth. On May 1, 1935, the New York Times broke the story on its front page that America was secretly building military air bases on the border with Canada in preparation for an invasion and aerial bombardment of its closest ally.

Oddly enough, the Times tried to diffuse the seriousness of the claim with its long, vague lead sentence:

“WASHINGTON, April 30 – President Roosevelt censured the House Military Affairs committee today for publishing secret testimony of army officers on the Wilcox Air Base Bill involving the United States’ relations with Canada, repudiated the views of the officers as not in line with administration policies, and gave assurances that this government would observe in letter and spirit its treaties with Canada that have meant unfortified frontiers for a century.”

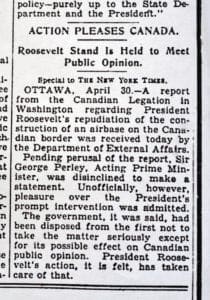

The story goes on in that vein for nearly 1,000 words and ends on the turn page with an equally vague response from Canada:

“OTTAWA, April 30 – A report from the Canadian Legation in Washington regarding President Roosevelt’s repudiation of the construction of an airbase on the Canadian border was received today by the Department of External Affairs.

“Pending perusal of the report, Sir George Perley, Acting Prime Minister, was disinclined to make a statement. Unofficially, however, pleasure over the President’s prompt intervention was admitted.”

What about Britain?

What Canada and the U.S. hadn’t taken into consideration was that Britain had no intention of rushing troops to Canada’s defence. It planned to surrender its colony to the Americans since there was no immediate threat to Britain’s livelihood. It was still reeling from the devastation of the First World War, the Depression and growing unrest in its colonies.

From this point on, though, Franklin D. Roosevelt determined to keep the military under a tighter rein, and eventually what prevented two neighbouring nations from coming to blows was the combined statesmanship of the U.S. president and Churchill. Both realized the real threat would come from Germany and Japan, and that Britain and the U.S. would be far better off as allies in the coming struggle.

America gradually abandoned plans for an invasion of Canada and the project was finally shelved in 1939. The plan was released to the public in 1974, when it caused a minor political stir but was quickly forgotten.

And that’s for the best. Imagine for a moment that Canada had been invaded by the U.S. Our lives would be dominated by American influences, Canadians would now be inundated with American popular music, watching American films, reading American magazines, following American sports.

Canadian culture would be pushed to the sidelines and American businesses would dominate our … oh, never mind.

To learn more about War Plan Red

The original plans for War Plan Red are available to the public in the American National Archive in Washington, D.C.

Kevin Lippert’s book about the program is titled War Plan Red: The United States’ Secret Plan to Invade Canada and Canada’s Secret Plan to Invade the United States, Princeton Architectural Press (June 2, 2015).

There’s an excellent British documentary on YouTube called America’s Planned War on Britain.

President Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill: Eventually what prevented Canada and the U.S. from coming to blows was the combined statesmanship of U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

*

Note to readers: please click the share buttons above or below. Forward this article to your email lists. Crosspost on your blog site, internet forums. etc.

Peter Bailey is an award-winning newspaper editor and writer with more than 40 years of experience. He lives in Hamilton, Ont.

Featured image: Troops would cross from Fort Drum, N.Y., to strike Ottawa. A second army would cross from Buffalo into Niagara to shut down Ontario’s hydroelectric plants, to occupy Hamilton’s steel industries, and to head to Toronto by road. More troops would cross from Detroit and a third group would head north to Winnipeg. A fourth group would attack Vancouver. (Source: Troy Media); all images in this article are from Troy Media