America’s “Open Door Policy” May Have Led Us to the Brink of Nuclear Annihilation

“Neither a man nor a crowd nor a nation can be trusted to act humanely or to think sanely under the influence of a great fear.” ― Bertrand Russell, Unpopular Essays (1950) [1]

The North Korean crisis presents people on the left to liberal spectrum with one of the greatest challenges we have ever faced. Now, more than ever, we have to put aside our natural fears and prejudices that surround the issue of nuclear weapons and ask hard questions that demand clear answers. It is time to step back and consider who the bully is on the Korean Peninsula, who poses a dire threat to international peace and even to the survival of the human species. It is far past time that we had a probing debate on Washington’s problem in North Korea and its military machine. Here is some food for thought on issues that are being swept under the carpet by knee jerk reactions—reactions that are natural for generations of Americans who have been kept in the dark about basic historical facts. Mainstream journalists and even many outside the mainstream at liberal and progressive news sources, uncritically regurgitate Washington’s deceptions, stigmatize North Koreans, and portray our current predicament as a fight in which all parties are equally culpable.

First of all, we have to face the unpalatable fact that we Americans, and our government above all, are the main problem. Like most people from the West, I know almost nothing about North Koreans, so I can say very little about them. All we can talk about with any confidence is Kim Jong-un’s regime. Restricting the discussion to that, we can say that his threats are not credible. Why? One simple reason:

Because of the disparity of power between the military capability of the U.S., including its current military allies, and North Korea. The difference is so vast it barely merits discussion, but here are the main elements:

U.S. bases: Washington has at least 15 military bases scattered throughout South Korea, many of them close to the border with North Korea. There are also bases scattered throughout Japan, from Okinawa in the far south all the way up north to Misawa Air Force Base.[2] The bases in South Korea have weapons with more destructive capacity than even the nuclear weapons that Washington kept in South Korea for the 30 years from 1958 to 1991.[3] Bases in Japan have Osprey aircraft that can ferry the equivalent volume of two city buses full of troops and equipment across to Korea on each trip.

Aircraft carriers: There are no less than three aircraft carriers in waters around the Korean Peninsula and their battle group of destroyers.[4] Most countries do not have even one aircraft carrier.

THAAD: In April of this year Washington deployed the THAAD (“terminal high area altitude defense”) system in spite of intense opposition from South Korean citizens.[5] It is only supposed to intercept North Korean incoming ballistic missiles on their downward descent, but Chinese officials in Beijing worry that the real purpose of THAAD is to “track missiles launched from China” since THAAD has surveillance capabilities.[6] Therefore, THAAD threatens North Korea indirectly also, by threatening its ally.

The South Korean military: This is one of the largest standing armed forces in the world, complete with a full-blown air force and conventional weapons more than sufficient to meet the threat of an invasion from North Korea.[7] The South Korean military is well-trained and well-integrated with the US military since they regularly engage in exercises such as the annual “massive sea, land and air exercises” called “Ulchi Freedom Guardian” involving tens of thousands of troops.[8] Not wasting an opportunity to intimidate Pyongyang, these were carried out at the end of August 2017 in spite of the rising tension.

Japanese military: The euphemistically named “Self-Defense Forces” of Japan are equipped with some of the most high-tech, offensive military equipment in the world, such as AWACS airplanes and Ospreys.[9] With Japan’s peace constitution, these weapons are “offensive” in more than one sense of the word.

Submarines with nuclear missiles: The US has submarines near the Korean Peninsula equipped with nuclear missiles that have “hard-target kill capability” thanks to a new “super-fuze” device that is being used to upgrade old thermonuclear warheads. This is now probably deployed on all US ballistic missile submarines.[10] “Hard-target kill capability” refers to their ability to destroy hardened targets such as Russian ICBM silos (i.e., underground nuclear missiles). These were previously very difficult to destroy. This indirectly threatens North Korea since Russia is one of the countries that could come to their aid in the event of a U.S. first strike.

As U.S. Defense Secretary James Mattis said, a war with North Korea would be “catastrophic.”[11] That is true—catastrophic primarily for Koreans, north and south, and possibly for other countries in the region, but not for the U.S.A. And it is also true that “backed up to the wall,” North Korean generals “will fight,” as Professor Bruce Cumings, the preeminent historian of Korea at the University of Chicago, emphasizes.[12] The U.S. would “totally destroy” the government in North Korea’s capital Pyongyang, and probably even all of North Korea, as U.S. President Trump threatened.[13] North Korea, in turn, would do some serious damage to Seoul, one of the world’s densest cities, cause millions of casualties in South Korea and tens of thousands in Japan. As the historian Paul Atwood writes, since we know that the “northern regime has nuclear weapons which will be launched at American bases [in South Korea] and Japan, we ought to be screaming from the rooftops that an American attack will unleash those nukes, potentially on all sides, and the ensuing desolation may rapidly devolve into a nightmarish day of reckoning for the entire human species.”[14]

No country in the world can threaten the US. Period. David Stockman, a former two-term Congressman from Michigan writes,

“No matter how you slice it, there just are no real big industrialized, high tech countries in the world which can threaten the American homeland or even have the slightest intention of doing so.”[15]

He asks rhetorically,

“Do you think [Putin] would be rash or suicidal enough to threaten the US with nuclear weapons?”

That’s someone with 1,500 “deployable nuclear warheads.”

“Siegfried Hecker, director emeritus of the Los Alamos National Laboratory and the last known U.S. official to inspect North Korea’s nuclear facilities, has calculated the size of North Korea’s arsenal at no more than 20 to 25 bombs.”[16] If it would be suicidal for Putin to start a war with the U.S., then that would be even truer for Kim Jong-un of North Korea, a country with one-tenth the population of the U.S. and little wealth.

The U.S. level of military preparedness goes way above and beyond what is necessary to protect South Korea. It directly threatens North Korea, China, and Russia. As Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. once stated, the U.S. is the “greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” That was true in his time and it is every bit as true now.

In the case of North Korea, the importance of its governments’ focus on violence is given recognition with the term “garrison state,”[17]how Cumings categorizes it. This term recognizes the undeniable fact that the people of North Korea spend a lot of their time preparing for war. No one calls North Korea the “greatest purveyor of violence” though.

Who has their finger on the button?

A leading American psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton recently emphasized “the potential unraveling of Donald Trump.”[18] He explains that Trump

“sees the world through his own sense of self, what he needs and what he feels. And he couldn’t be more erratic or scattered or dangerous.”

During his election campaign Trump not only argued for the nuclearization of Japan and South Korea, but expressed a horrifying interest in actually using such weapons. That Donald Trump, a man thought to be mentally unstable, has at his disposal weapons capable of annihilating the planet many times over represents a truly terrifying threat, i.e., a credible threat.

From this perspective, the so called “threat” of North Korea comes to look rather like the proverbial storm in a teacup.

If you feel afraid of Kim Jong-un, think how terrified North Koreans must be. The possibility of Trump letting an unstoppable nuclear genie out of the bottle surely ought to be a wake up call to all people anywhere on the political spectrum to wake up and act before it is too late.

If our fear of Kim Jong-un striking us first is irrational, and if the idea of his being on a “suicide mission” right now is unfounded—since he, his generals, and his government officials are the beneficiaries of a dynasty that gives them significant power and privileges—then what is the source of our irrationality, i.e., the irrationality of people in the U.S.? What is all the hype about? I would like to argue that one source of this kind of thinking, the kind of thinking we see all the time at the domestic level, is actually racism. This form of prejudice, like other kinds of mass propaganda, is actively encouraged by a government that underpins a foreign policy guided by the greed of the 1% rather than the needs of the 99%.

The “open door” fantasy

The core of our foreign policy can be summed up with the regrettably still extant propaganda slogan known as the “Open Door Policy,” as explained recently by Atwood.[19] You might remember this old phrase from a high school history class. Atwood’s brief survey of the history of the Open Door Policy shows us why it can be a real eye opener, providing the key to understanding what has been happening lately with North Korea-Washington relations. Atwood writes that

“the U.S. and Japan had been on a collision course since the 1920s and by 1940, in the midst of the global depression, were locked in a mortal struggle over who would ultimately benefit most from the markets and resources of Greater China and East Asia.”

If one had to explain what the cause of the Pacific War was, that one sentence would go a long way. Atwood continues,

“The real reason the U.S. opposed the Japanese in Asia is never discussed and is a forbidden subject in the establishment media as are the real motives of American foreign policy writ large.”

It is sometimes argued that the U.S. blocked Japan’s access to resources in East Asia, but the problem is portrayed in a one-sided way, as one of Japanese greed and will to dominate causing the conflict rather than that of Washington.

Atwood aptly explains,

“Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere was steadily closing the ‘Open Door’ to American penetration of and access to the profitable riches of Asia at the critical moment. As Japan took control of East Asia the U.S. moved the Pacific Fleet to Hawaii in striking distance of Japan, imposed economic sanctions, embargoed steel and oil and in August 1941 issued an overt ultimatum to quit China and Vietnam ‘or else.’ Seeing the latter as the threat it was, Japan undertook what to Tokyo was the pre-emptive strike at Hawaii.”

What many of us have been led to believe, that Japan just went berserk because it was controlled by an undemocratic and militaristic government, was in fact the old story of violence over who owns the world’s finite resources.

Indeed, the view of Cumings, who has spent a lifetime researching Korean history, especially as it relates to U.S.-Korea relations, fits well with Atwood’s:

“Ever since the publication of the ‘open door notes’ in 1900 amid an imperial scramble for Chinese real estate, Washington’s ultimate goal had always been unimpeded access to the East Asian region; it wanted native governments strong enough to maintain independence but not strong enough to throw off Western influence.”[20]

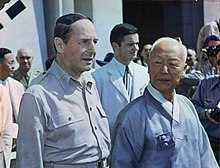

Atwood’s brief but powerful article gives one the big picture of the Open Door Policy, while through Cumings’ work, one can learn about the particulars of how it was implemented in Korea during the American occupation of the country after the Pacific War, through the not-free and not-fair election of the first South Korean dictator Syngman Rhee (1875–1965), and the civil war in Korea that followed. “Unimpeded access to the East Asian region” meant access to markets for the elite American business class, with successful domination of those markets an extra plus.

Syngman Rhee and Douglas MacArthur at the Ceremony inaugurating the government of the Republic of Korea. (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

The problem was that anticolonial governments gained control in Korea, Vietnam, and China. These governments wanted to use their resources for independent development to benefit the population of their country, but that was, and still is, a red flag for the “bull” that is the American military-industrial complex. As a result of those movements for independence, Washington went for “second-best.” “American planners forged a second-best world that divided Asia for a generation.”[21] One collaborationist Pak Hung-sik said that “revolutionists and nationalists” were the problem, i.e., people who believed that Korean economic growth should benefit mainly Koreans, and who thought Korea should go back to being some kind of integrated whole (as it had been for at least 1,000 years).

“Yellow peril” racism

Since such radical thinking as independent “nationalism” has always had to be stamped out at any price, a major investment in costly wars would be necessary. (The public being the investors and corporations the stockholders!) Such an investment would require the cooperation of millions of Americans. That is where the “Yellow Peril” ideology came in handy. The Yellow Peril is a mutant propaganda concept that has worked hand in glove with the Open Door Policy, in whatever form it is currently manifesting itself as.[22] The connections are vividly demonstrated in the extremely high-quality reproductions of Yellow Peril propaganda from around the time of the first Sino-Japanese War (1894–95) interspersed with an essay by the professor of history Peter C. Perdue and the Creative Director of Visualizing Cultures Ellen Sebring at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[23] As their essay explains,

the “reason expansionist foreign powers were intent on carving China into spheres of influence was, after all, their perception that untold profits would derive from this. This glittering sack of gold was, indeed, the other side of the ‘yellow peril’.”

One propaganda image is a stereotypical picture of a Chinese man, who he is actually sitting on bags of gold on the other side of the sea.

Western racism towards people of the East has been long demonstrated with the ugly racist word “gook.” Fortunately, that word has died out. Koreans did not appreciate being treated with racial slurs such as this,[24] no more than Filipinos or Vietnamese.[25] (In Vietnam there was an unofficial but frequently deployed “mere-gook rule” or “MGR,” that said that Vietnamese were mere animals who could be killed or abused at will). This term was used to refer to Koreans, too, both north and south. Cumings tells us that the “respected military editor” Hanson Baldwin during the Korean War compared Koreans to locusts, barbarians, and the hordes of Genghis Khan, and that he used words to describe them like “primitive.”[26]Washington’s ally Japan also allows racism against Koreans to thrive and only passed its first law against hate speech in 2016.[27]Unfortunately, it is a toothless law and only a first step.

The irrational fear of non-Christian spiritual beliefs, films about the diabolical Fu Manchu,[28] and racist media portrayal over the course of the 20th century all played a part in creating a culture in which George W. Bush could, with a straight face, designate North Korea one of the three “Axis of Evil” countries after 9/11.[29] Not only irresponsible and influential journalists at Fox News but other news networks and papers actually repeat this cartoonish label, using it as a “shorthand” for a certain U.S. policy.[30] The term “axis of hatred” was almost used, before being edited out of the original speech. But the fact that these terms are taken seriously is a mark of dishonor on “our” side, a mark of the evil and hatred in our own societies.

Trump’s racist attitudes toward people of color is so obvious it hardly requires documenting.

Postwar relations between the two Koreas and Japan

With this prejudice in the background—this prejudice that people in the U.S. harbor toward Koreans—it is no surprise that few Americans have stomped their feet and yelled, “enough is enough” regarding Washington’s postwar mistreatment of them. One of the first and most egregious ways in which Washington wronged Koreans after the Pacific War was during the International Military Tribunal for the Far East that convened in 1946: the sexual slavery system of the Japanese military (euphemistically called the “comfort women” system) was not prosecuted, making later military-spawned sex trafficking of any country, including the U.S., more likely to reoccur. As Gay J. McDougall of the U.N. wrote in 1998,

“…the lives of women continue to be undervalued. Sadly, this failure to address crimes of a sexual nature committed on a massive scale during the Second World War has added to the level of impunity with which similar crimes are committed today.”[31]

The sexual crimes against Korean women by U.S. troops of the past and today are linked with those by Japanese troops of the past.[32] The lives of women in general were undervalued, but the lives of Korean women in particular were undervalued as those of “gooks”—sexism plus racism.

The U.S. military’s lax attitude toward sexual violence was reflected in Japan in the way that Washington permitted American troops to prostitute Japanese women, victims of Japanese government-sponsored sex trafficking, called the “Recreation and Amusement Association,” which was openly made available for the pleasure of all allied troops.[33] In the case of Korea, it was discovered through the transcripts of South Korean parliamentary hearings that “in one exchange in 1960, two lawmakers urged the government to train a supply of prostitutes to meet what one called the ‘natural needs’ of allied soldiers and prevent them from spending their dollars in Japan instead of South Korea. The deputy home minister at the time, Lee Sung-woo, replied that the government had made some improvements in the ‘supply of prostitutes’ and the ‘recreational system’ for American troops.”[34]

Source: Japan Today

It must also not be forgotten that U.S. soldiers have raped Korean women outside of brothels. Japanese women, like Korean women, have been the target of sexual violence during the U.S. occupation there and near U.S. military bases—sexually trafficked women as well as women just walking down the street.[35] Victims in both countries still suffer from physical wounds and PTSD—both a result of occupation and military bases. It is a crime of our society that the “boys will be boys” attitude of the U.S. military culture continues. It should have been nipped in the bud at the International Military Tribunal for the Far East.

MacArthur’s relatively humane post-war liberalization of Japan had included moves towards democratization such as land reform, workers’ rights, and permitting the collective bargaining of labor unions; the purging of ultranationalist government officials; and the reigning in of the Zaibatsu (i.e., Pacific War-time business conglomerates, who profited from war) and organized crime syndicates; last but not least, a peace constitution unique in the world with its Article 9 “Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right of the nation and the threat or use of force as means of settling international disputes.” Obviously, much of this would be welcome to Koreans, especially excluding the ultranationalists from power and the peace constitution.

Unfortunately, such movements are never welcome to corporations or the military-industrial complex, so in early 1947 it was decided that Japanese industry would once again become the “workshop of East and Southeast Asia,” and that Japan and South Korea would receive support from Washington for economic recovery along the lines of the Marshall Plan in Europe.[36] One sentence in a note from Secretary of State George Marshall to Dean Acheson in January 1947 sums up the U.S. policy on Korea that would be in effect from that year until 1965: “organize a definite government of South Korea and connect up [sic] its economy with that of Japan.” Acheson succeeded Marshall as Secretary of State from 1949 to 1953. He “became the prime internal advocate of keeping southern Korea in the zone of American and Japanese influence, and single-handedly scripted the American intervention in the Korean War,” in Cumings’ words.

As a result, Japanese workers lost various rights and had less bargaining power, the euphemistically-named “Self-Defense Forces” were established, and the ultranationalists such as Prime Minister Abe’s grandfather Kishi Nobusuke (1896–1987) were allowed to return to government. The remilitarization of Japan continues today, threatening both Koreas as well as China and Russia.

The Pulitzer Prize-winning historian John Dower notes one tragic result that followed from the two peace treaties for Japan that came into effect on the day that Japan regained its sovereignty 28 April 1952:

“Japan was inhibited from moving effectively toward reconciliation and reintegration with its nearest Asian neighbors. Peace-making was delayed.”[37]

Washington blocked peace-making between Japan and the two main neighbors that it had colonized, Korea and China, by instituting a “separate peace” that excluded both Koreas as well as the People’s Republic of China (PRC) from the whole process. Washington twisted Japan’s arm to gain their cooperation by threatening to continue the occupation that had started with General Douglas MacArthur (Douglas MacArthur (1880–1964). Since Japan and South Korea did not normalize relations until June 1965, and a peace treaty between Japan and the PRC was not signed until 1978, there was a long delay, during which according to Dower,

“The wounds and bitter legacies of imperialism, invasion, and exploitation were left to fester—unaddressed and largely unacknowledged in Japan. And ostensibly independent Japan was propelled into a posture of looking east across the Pacific to America for security and, indeed, for its very identity as a nation.”

Thus Washington drove a wedge between Japanese on the one hand and Koreans and Chinese on the other, denying Japanese a chance to reflect on their wartime deeds, apologize, and rebuild friendly ties. Japanese discrimination against Koreans and Chinese is well-known, but only a tiny number of well-informed people understand that Washington is also to blame.

Don’t let the door close in East Asia

To return to Atwood’s point about the Open Door Policy, he succinctly and aptly defines this imperialistic doctrine thus: “American finance and corporations should have untrammeled right of entry into the marketplaces of all nations and territories and access to their resources and cheaper labor power on American terms, sometimes diplomatically, often by armed violence.”[38] He explains how this doctrine took shape. After our Civil War (1861-65), the U.S. Navy maintained a presence “throughout the Pacific Ocean especially in Japan, China, Korea and Vietnam where it undertook numerous armed interventions.” The Navy’s goal was “to ensure law and order and ensure economic access…while preventing European powers…from obtaining privileges that would exclude Americans.”

Beginning to sound familiar?

The Open Door Policy led to some wars of intervention, but the U.S. did not actually begin to actively attempt to thwart anticolonial movements in East Asia, according to Cumings, until the 1950 National Security Council report 48/2, which was two years in the making. It was entitled “Position of the United States with Respect to Asia” and it established a totally new plan that was “utterly unimagined at the end of World War II: it would prepare to intervene militarily against anticolonial movements in East Asia—first Korea, then Vietnam, with the Chinese Revolution as the towering backdrop.”[39] This NSC 48/2 expressed opposition to “general industrialization.” In other words, it would be OK for countries in East Asia to have niche markets, but we don’t want them developing full-scale industrialization as the US did, because then they will be able to compete with us in fields where we have a “comparative advantage.”[40] That is what NSC 48/2 termed “national pride and ambition,” which would “prevent the necessary degree of international cooperation.”

The de-unification of Korea

Before Japan’s annexation of Korea in 1910, the vast majority of Koreans had been “peasants, most of them tenants working land held by one of the world’s most tenacious aristocracies,” i.e., the yangbanaristocracy.[41] The word is composed of two Chinese characters, yang meaning “two” and ban meaning “group.” The aristocratic ruling class had been made up of two groups—the civil servants and the military officers. And slavery was not abolished in Korea until 1894.[42] The U.S. occupation and the new, unpopular South Korean government of Syngman Rhee that was established in August 1948 pursued policies of divide and conquer that, after 1,000 years of unity, pushed the Korean Peninsula into a full-on, civil war with divisions along class lines.

So what is the crime of the majority of Koreans for which they are now about to be punished? Their first crime is that they were born into an exploited economic class in a country sandwiched between two relatively rich and powerful countries, i.e., China and Japan. After suffering tremendously under Japanese colonialism for over 30 years, they enjoyed a brief feeling of liberation that started in the summer of 1945, but soon the U.S. took over from where the Empire of Japan had left off. Their second crime was resisting this second enslavement under Washington-backed Syngman Rhee, sparking the Korean War. And third, many of them aspired to a fairer distribution of the wealth of their country. These last two types of insurrection got them in trouble with Bully Number One, who as noted above, had secretly decided to not allow “general industrialization” in its NSC 48/2, consistent with its general geopolitical approach, severely punishing countries that aspire to independent economic development.

Perhaps partly due to the veneer of legitimacy that the new, weak, and U.S.-dominated U.N. bestowed on Syngman Rhee’s government, few intellectuals in the West have looked into the atrocities committed by the U.S. during its occupation of Korea, or even into the specific atrocities that that accompanied the establishment of Rhee’s government. Between 100,000 and 200,000 Koreans were killed by the South Korean government and the U.S. occupation forces before June 1950, when the “conventional war” began, according to Cumings’ research, and “300,000 people were detained and executed or simply disappeared by the South Korean government in the first few months after conventional war began.”[43] (My italics). So putting down the Korean resistance in its early stages entailed the slaughtering of around a half million human beings. This alone is evidence that huge numbers of Koreans in the south, not only the majority of Koreans in the north (millions of whom were slaughtered during the Korean War), did not welcome with open arms their new U.S.-backed dictators.

The start of the “conventional war,” by the way, is usually marked as 25 June 1950, when Koreans in the north “invaded” their own country, but war in Korea was already well underway by early 1949, so although there is a widely-held assumption that the War started in 1950, Cumings rejects that assumption.[44] For example, there was a major peasant war on Jeju Island in 1948-49 in which somewhere between 30,000 and 80,000 residents were killed, out of a population of 300,000, some of the them killed directly by Americans and many of them indirectly by Americans in the sense that Washington assisted with the state violence of Syngman Rhee.[45] In other words, it would be difficult to blame the Korean War on the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), but easy to blame it on Washington and Syngman Rhee.

After all the suffering that the U.S. has caused Koreans, both north and south, it should not come as any surprise that the government of North Korea is anticolonial and anti-American, and that some Koreans in the North cooperate with Kim Jong-un’s government in helping the North prepare for war with the U.S., even when the government is undemocratic. (At least the clips we are shown over and over on mainstream TV, of soldiers marching indicate some level of cooperation). In Cumings’ words, “The DPRK is not a nice place, but it is an understandable place, an anticolonial and anti-imperial state growing out of a half-century of Japanese colonial rule and another half-century of continuous confrontation with a hegemonic United States and a more powerful South Korea, with all the predictable deformations (garrison state, total politics, utter recalcitrance to the outsider) and with extreme attention to infringements of its rights as a nation.”[46]

What now?

When Kim Jong-un issues verbal threats, they are hardly ever credible. When U.S. President Trump threatens North Korea, it is terrifying. A nuclear war started on the Korean Peninsula could “throw up enough soot and debris to threaten the global population,”[47] so he is actually threatening humankind’s very existence.

One only need check the so-called “Doomsday Clock” to see how urgent it is that we act now.[48] Many well-informed people have succumbed, by and large, to a narrative that demonizes everyone in North Korea. Regardless of political beliefs, we must rethink and reframe the current debate regarding this U.S. crisis—Washington’s escalation of the tension. This will require seeing the looming “unthinkable,” not as an isolated event but as an inevitable result of the flow of the violent historical trends of imperialism and capitalism over time—not only “seeing,” but acting in consort to radically change our species propensity for violence.

Joseph Essertier is an associate professor at the Nagoya Institute of Technology in Japan.

Notes

[1] Bertrand Russell, Unpopular Essays (Simon And Schuster, 1950)

[2] “US Military Bases in Japan Military Bases”

[3] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History (W.W. Norton, 1988) p. 477.

Alex Ward, “South Korea Wants the US to Station Nuclear Weapons in the Country. That’s a Bad Idea.” Vox (5 September 2017).

[4] Alex Lockie, “US sends third aircraft carrier to the Pacific as massive armada looms near North Korea,” Business Insider (5 June 2017)

[5] Bridget Martin, “Moon Jae-In’s THAAD Conundrum: South Korea’s “Candlelight President” Faces Strong Citizen Opposition on Missile Defense,” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 15:18:1 (15 September 2017).

[6] Jane Perlez, “For China, a Missile Defense System in South Korea Spells a Failed Courtship,” New York Times (8 July 2016)

[7] Bruce Klingner, “South Korea: Taking the Right Steps to Defense Reform,” the Heritage Foundation (19 October 2011)

[8] Oliver Holmes, “US and South Korea to stage huge military exercise despite North Korea crisis,” The Guardian (11 August 2017)

[9] “Japan-Airborne Warning and Control System (AWACS) Mission Computing Upgrade (MCU),” Defense Security Cooperation Agency (26 September 2013)

[10] Hans M. Kristensen, Matthew McKinzie, and Theodore A. Postol, “How US Nuclear Force Modernization Is Undermining Strategic Stability: The Burst-Height Compensating Super-Fuze,” Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists (March 2017)

One submarine was moved to the region in April 2017. See Barbara Starr, Zachary Cohen and Brad Lendon, “US Navy Guided-missile Sub Calls in South Korea,” CNN (25 April 2017).

There must be at least two in the region however. See “Trump tells Duterte of two U.S. nuclear subs in Korean waters: NYT,” Reuters (24 May 2017)

[11] Dakshayani Shankar, “Mattis: War with North Korea would be ‘catastrophic’,” ABC News (10 Aug 2017)

[12] Bruce Cumings, “The Hermit Kingdom Bursts Upon Us,” LA Times (17 July 1997)

[13] David Nakamura and Anne Gearan, “In U.N. speech, Trump threatens to ‘totally destroy North Korea’ and calls Kim Jong Un ‘Rocket Man’,” Washington Post (19 September 2017)

[14] Paul Atwood, “Korea? It’s Always Really Been About China!,” CounterPunch (22 September 2017)

[15] David Stockman, “The Deep State’s Bogus ‘Iranian Threat’,” Antiwar.com (14 October 2017)

[16] Joby Warrick, Ellen Nakashima, and Anna Fifield “North Korea now making missile-ready nuclear weapons, U.S. analysts say,” Washington Post (8 August 2017)

[17] Bruce Cumings, North Korea: Another Country (The New Press, 2003) p. 1.

[18] Transcript of interview, “Psychiatrist Robert Jay Lifton on Duty to Warn: Trump’s ‘Relation to Reality’ is Dangerous to Us All,” DemocracyNow! (13 October 2017)

[19] Atwood, “Korea? It’s Always Really Been About China!” CounterPunch.

[20] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 8, section entitled “A Military-Industrial Complex,” the 7th paragraph.

[21] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 8, section entitled “A Military-Industrial Complex,” the 7th paragraph.

[22] Aaron David Miller and Richard Sokolsky, “The ‘axis of evil’ is back,” CNN (26 April 2017) l

[23] “The Boxer Uprising—I: The Gathering Storm in North China (1860-1900),” MIT Visualizing Cultures, Creative Commons license website:

[24] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 4, 3rd paragraph.

[25] Nick Turse tells the history of the ugly racism associated with this word in Kill Anything that Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam (Picador, 2013), Chapter 2.

[26] For the original symbolically violent article, see Hanson W. Baldwin, “The Lesson of Korea: Reds’ Skill, Power Call for Reappraisal of Defense Needs against Sudden Invasion,” New York Times (14 July 1950)

[27] Tomohiro Osaki, “Diet passes Japan’s first law to curb hate speech,” Japan Times (24 May 2016)

[28] Julia Lovell, “The Yellow Peril: Dr Fu Manchu & the Rise of Chinaphobia by Christopher Frayling – review,” The Guardian (30 October 2014)

[29] Christine Hong, “War by Other Means: The Violence of North Korean Human Rights,” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 12:13:2 (30 March 2014)

[30] Lucas Tomlinson and The Associated Press, “‘Axis of Evil’ still alive as North Korea, Iran launch missiles, flout sanctions,” Fox News (29 July 2017)

Jaime Fuller, “The 4th best State of the Union address: ‘Axis of evil,’ Washington Post (25 January 2014)

[31] Caroline Norma, The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery during the China and Pacific Wars (Bloomsbury, 2016), Conclusion, 4th paragraph.

[32] Tessa Morris-Suzuki, “You Don’t Want to Know About the Girls? The ‘Comfort Women’, the Japanese Military and Allied Forces in the Asia-Pacific War,” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 13:31:1 (3 August 2015).

[33] John W. Dower, Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. (Norton, 1999)

[34] Katharine H.S. Moon, “Military Prostitution and the U.S. Military in Asia,” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus Volume 7:3:6 (12 January 2009)

http://apjjf.org/-Katharine-H.S.-Moon/3019/article.html

[35] Norma, The Japanese Comfort Women and Sexual Slavery during the China and Pacific Wars, Chapter 6, the last paragraph of section entitled “Prostituted victims till the very end.”

[36] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 5, the second-to-the-last paragraph of the first section before the “Southwest of Korea during the Military Government.”

[37] John W. Dower, “The San Francisco System: Past, Present, Future in U.S.-Japan-China Relations,” Asia Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 12:8:2 (23 February 2014)

[38] Atwood, “Korea? It’s Always Really Been About China!” CounterPunch.

[39] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 8, section entitled “A Military-Industrial Complex,” the 6th paragraph.

[40] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 8, section entitled “A Military-Industrial Complex,” the 9th paragraph.

[41] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 1, the 3rd paragraph.

[42] Cumings, North Korea: Another Country, Chapter 4, 2nd paragraph.

[43] Cumings, “A Murderous History of Korea,” London Review of Books 39:10 (18 May 2017).

[44] Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History, p. 238.

[45] Cumings, The Korean War, Chapter 5, “The Jeju Insurgency.”

[46] Cumings, North Korea: Another Country, Chapter 2, “American Nuclear Threats” section, the last paragraph.

[47] Bruce Cumings, “A Murderous History of Korea,” London Review of Books (18 May 2017). This is Cumings’ best brief-but-thorough, concise article on Korean history as it relates to the present crisis.

[48] Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Featured image is from frankieleon | CC by 2.0.